Archive for the ‘Publishing’ Category

A Geodesic Life

After three years of work—and more than a few twists and turns—my latest book, Inventor of the Future: The Visionary Life of Buckminster Fuller, is finally here. I think it’s the best thing that I’ve ever done, or at least the one book that I’m proudest to have written. After last week’s writeup in The Economist, a nice review ran this morning in the New York Times, which is a dream come true, and you can check out excerpts today at Fast Company and Slate. (At least one more should be running this weekend in The Daily Beast.) If you want to hear more about it from me, I’m doing a virtual event today sponsored by the Buckminster Fuller Institute, and on Saturday August 13, I’ll be holding a discussion at the Oak Park Public Library with Sarah Holian of the Frank Lloyd Wright Trust, which will be also be available to view online. There’s a lot more to say here, and I expect to keep talking about Fuller for the rest of my life, but for now, I’m just delighted and relieved to see it out in the world at last.

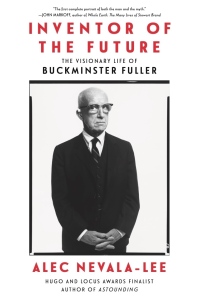

Inventing the future

I realize that I’m well overdue for an update on my new book, Inventor of the Future: The Visionary Life of Buckminster Fuller, which is scheduled to be published by Dey Street Books / HarperCollins on August 2. Yesterday, I delivered my revisions to the copy edit, so I’ve essentially reached the end of a process that has lasted three long and challenging years. The result, I think, is the best thing I’ve ever done. It’s a big book—over six hundred pages including the back matter and index—but Fuller more than justifies it, and I hope that it will appeal to both his existing admirers and readers who are encountering him for the first time. (Even if you’re an obsessive Fuller fan, I can guarantee that there’s a lot here that you haven’t seen before.) I’m also delighted by the cover, which features a remarkable portrait of Fuller by Richard Avedon that has rarely been reproduced elsewhere. Obviously, I’ll have a lot more to say about this over the next few months, so check back soon for more!

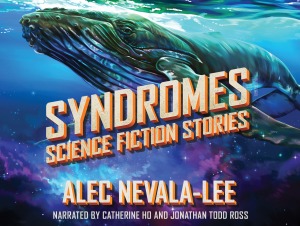

Listening to Syndromes

I’m pleased beyond words to announce that my audio short fiction collection Syndromes, which includes all thirteen of my stories from Analog Science Fiction and Fact, has just been released by Recorded Books. (It was originally scheduled to drop in June, but in light of recent developments, it became one of a handful of titles to come out before everything shut down on that end. I’m glad that it managed to appear just under the wire, and I’m especially delighted by the dazzling cover art by Will Lee.) The wonderful narrators Jonathan Todd Ross and Catherine Ho trade reading duties on “Ernesto,” “The Spires,” “The Whale God,” “The Last Resort,” “Kawataro,” “Cryptids,” “The Boneless One,” “Inversus,” “Stonebrood,” “The Voices,” “The Proving Ground,” and “At the Fall,” before joining forces at the end for a new version of my audio play “Retention,” which strikes me as the standout track. Every story has been revised to fit into a single interconnected timeline, which stretches from 1937 through the near future, and even if you’ve read some of them before, you’ll discover a few new surprises. You can purchase it at Amazon or stream it through Audible or Libro.fm, so I hope that some of you will check it out—and let me know what you think!

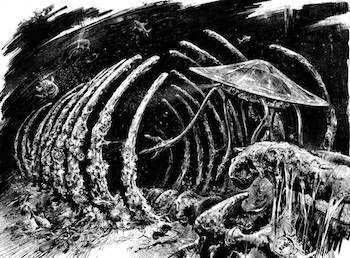

“At the Fall” and Beyond

The May/June issue of Analog Science Fiction and Fact includes my new novelette “At the Fall,” a big excerpt of which you can read now on the magazine’s official site. It’s one of my favorite stories that I’ve ever written, and I’m especially pleased by the interior illustration by Eldar Zakirov, pictured above, which you can see in greater detail here. I don’t think I’ll have the chance to write up the kind of extended account of this story’s conception that I’ve provided for other works in the past, but if you’re curious about its origins, Analog has posted a fun conversation on its blog in which I talk about it with Frank Wu, the author of “In the Absence of Instructions to the Contrary,” which appeared in the magazine a few years ago. (Our stories have a number of interesting parallels that only came to light after I wrote and submitted mine, and I think that the result is a nice case study of what happens when two writers end up independently pursuing a similar idea.) There’s also a thoughtful editorial by former Analog editor Stanley Schmidt about his relationship with John W. Campbell, inspired by a panel that we held at last year’s World Science Fiction Convention. Enjoy!

Love and Rockets

I’m delighted to share the news that Astounding is a 2019 Hugo Award Finalist for Best Related Work, along with a slate of highly deserving nominees. (The other finalists include Archive of Our Own, a project of the Organization for Transformative Works; the documentary The Hobbit Duology by Lindsay Ellis and Angelina Meehan; An Informal History of the Hugos by Jo Walton; The Mexicanx Initiative Experience at Worldcon 76 by Julia Rios, Libia Brenda, Pablo Defendini, and John Picacio; and Conversations on Writing by Ursula K. Le Guin and David Naimon. It’s a strong ballot, and I’m honored to be counted in such good company.) It feels like the high point of a journey that began with an announcement on this blog more than three years ago, and it isn’t over yet—I’m definitely going to be attending the World Science Fiction Convention in Dublin, which runs from August 15 to 19, and while I don’t know what the final outcome will be, I’m grateful to have made it even this far. The Hugos are an important part of the history that this book explores, and I’m thankful for the chance to be even a tiny piece of that story.

A Fuller Life

I’m pleased to announce that I’ve finally figured out the subject of my next book, which will be a biography of the architect and futurist Buckminster Fuller. If you’re a regular reader of this blog, you probably know how much Fuller means to me, and I’m looking forward to giving him the comprehensive portrait that he deserves. (Honestly, that’s putting it mildly. I’ve known for over a week that I’ll have a chance to tackle this project, and I still can’t quite believe that it’s really happening. And I’m especially happy that my current publisher has agreed to give me a shot at it.) At first glance, this might seem like a departure from my previous work, but it presents an opportunity to explore some of the same themes from a different angle, and to explore how they might play out in the real world. The timelines of the two projects largely coincide, with a group of subjects who were affected by the Great Depression, World War II, the Cold War, and the social upheavals of the sixties. All of them had highly personal notions about the fate of America, and Fuller used physical artifacts much as Campbell, Asimov, and Heinlein employed science fiction—to prepare their readers for survival in an era of perpetual change. Fuller’s wife, Anne, played an unsung role in his career that recalls many of the women in Astounding. Like Campbell, he approached psychology as a category of physics, and he hoped to turn the prediction of future trends into a science in itself. His skepticism of governments led him to conclude that society should be changed through design, not political institutions, and like many science fiction writers, he acted as if all disciplines could be reduced to subsets of engineering. And for most of his life, he insisted that complicated social problems could be solved through technology.

Most of his ideas were expressed through the geodesic dome, the iconic work of structural design that made him famous—and I hope that this book will be as much about the dome as about Fuller himself. It became a universal symbol of the space age, and his reputation as a futurist may have been founded largely on the fact that his most recognizable achievement instantly evoked the landscape of science fiction. From the beginning, the dome was both an elegant architectural conceit and a potent metaphor. The concept of a hemispherical shelter that used triangular elements to enclose the maximum amount of space had been explored by others, but Fuller was the first to see it as a vehicle for social change. With design principles that could be scaled up or down without limitation, it could function as a massive commercial pavilion or as a house for hippies. (Ken Kesey dreamed of building a geodesic dome to hold one of his acid tests.) It could be made out of plywood, steel, or cardboard. A dome could be cheaply assembled by hand by amateur builders, which encouraged experimentation, and its specifications could be laid out in a few pages and shared for free, like the modern blueprints for printable houses. It was a hackable, open-source machine for living that reflected a set of tools that spoke to the same men and women who were teaching themselves how to code. As I noted here recently, a teenager named Jaron Lanier, who was living in a tent with his father on an acre of desert in New Mexico, used nothing but the formulas in Lloyd Kahn’s Domebook to design and build a house that he called “Earth Station Lanier.” Lanier, who became renowned years later as the founder of virtual reality, never got over the experience. He recalled decades later: “I loved the place; dreamt about it while sleeping inside it.”

During his lifetime, Fuller was one of the most famous men in America, and he managed to become an idol to both the establishment and the counterculture. In the three decades since his death, his reputation has faded, but his legacy is visible everywhere. The influence of his geodesic structures can be seen in the Houston Astrodome, at Epcot Center, on thousands of playgrounds, in the dome tents favored by backpackers, and in the emergency shelters used after Hurricane Katrina. Fuller had a lasting impact on environmentalism and design, and his interest in unconventional forms of architecture laid the foundation for the alternative housing movement. His homegrown system of geometry led to insights into the biological structure of viruses and the logic of communications networks, and after he died, he was honored by the discoverers of a revolutionary form of carbon that resembled a geodesic sphere, which became known as fullerene, or the buckyball. And I’m particularly intrigued by his parallels to the later generation of startup founders. During the seventies, he was a hero to the likes of Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs, who later featured him prominently in the first “Think Different” commercial, and he was the prototype of the Silicon Valley types who followed. He was a Harvard dropout who had been passed over by the college’s exclusive social clubs, and despite his lack of formal training, he turned himself into an entrepreneur who believed in changing society through innovative products and environmental design. Fuller wore the same outfit to all his public appearances, and his personal habits amounted to an early form of biohacking. (Fuller slept each day for just a few hours, taking a nap whenever he felt tired, and survived mostly on steak and tea.) His closest equivalent today may well be Elon Musk, which tells us a lot about both men.

And this project is personally significant to me. I first encountered Fuller through The Whole Earth Catalog, which opened its first edition with two pages dedicated to his work, preceded by a statement from editor Stewart Brand: “The insights of Buckminster Fuller initiated this catalog.” I was three years old when he died, and I grew up in the shadow of his influence in the Bay Area. The week before my freshman year in high school, I bought a used copy of his book Critical Path, and I tried unsuccessfully to plow through Synergetics. (At the time, this all felt kind of normal, and it’s only when I look back that it seems strange—which tells you a lot about me, too.) Above all else, I was drawn to his reputation as the ultimate generalist, which reflected my idea of what my life should be, and I’m hugely excited by the prospect of returning to him now. Fuller has been the subject of countless other works, but never a truly authoritative biography, which is a project that meets both Susan Sontag’s admonition that a writer should try to be useful and the test that I stole from Lin-Manuel Miranda: “What’s the thing that’s not in the world that should be in the world?” Best of all, the process looks to be tremendously interesting for its own sake—I think it’s going to rewire my brain. It also requires an unbelievable amount of research. To apply the same balanced, fully sourced, narrative approach to his life that I tried to take for Campbell, I’ll need to work through all of Fuller’s published work, a mountain of primary sources, and what might literally be the largest single archive for any private individual in history. I know from experience that I can’t do it alone, and I’m looking forward to seeking help from the same kind of brain trust that I was lucky to have for Astounding. Those of you who have stuck with this blog should be prepared to hear a lot more about Fuller over the next three years, but I wouldn’t be doing this at all if I didn’t think that you might find it interesting. And who knows? He might change your life, too.

Quote of the Day

Typewritten manuscripts, which take up more pages than printed texts, deceive the author by creating an illusion of great distance between things that are so close to one another that they repeat themselves crassly; they tend in general to shift the proportions in favor of the author’s comfort. For a writer capable of self-reflection, print becomes a critique of his writing: it creates a path from the external to the internal. For this reason publishers should be advised to be tolerant of authors’ corrections.

Beyond the golden age

On August 13, 2015, I sat down to write an email to my agent. I was going through a challenging period in my career—I had just finished a difficult suspense novel that ended up never being sold—and I wasn’t exactly sure what would come next. As I weighed my options, I found myself thinking about turning to nonfiction, which was a prospect that I had occasionally contemplated. One possible subject had caught my attention, and that morning, for the first time ever, I put it into words. I wrote:

I’ve been thinking about a book on John W. Campbell, Jr., the pulp author and editor who ran Astounding Science Fiction, later known as Analog, for more than three decades. Campbell’s fingerprints are on everything from I, Robot to Dune to Star Trek—Isaac Asimov called him “the most powerful force in science fiction ever”—and his influence on global culture is incalculable. Late in his life, he became increasingly erratic and conservative, embraced a range of crackpot theories, and played an important role in the early history of dianetics and Scientology. There’s a tremendous amount of fascinating material available in his published letters, in his editorials, in his own fiction—he wrote the original story that became the basis for The Thing—and in the reminiscences of nearly every major science fiction writer from the first half of this century. Yet there’s never been a proper biography of Campbell or consideration of his legacy. And I’m starting to think that I might just be the guy to write it.

And I concluded: “It’s a big topic, but if properly handled, I think it shows real promise. I’d love to discuss further today, if possible.”

That was the beginning of the long road that led to Astounding: John W. Campbell, Isaac Asimov, Robert A. Heinlein, L. Ron Hubbard, and the Golden Age of Science Fiction, which is finally being released today. But there were times when I feared that it would never get past the daydream stage. Based on the ensuing email exchange, it sounds like my agent and I spoke about it over the phone that afternoon, and while I don’t recall much about our discussion, I remember that he was encouraging, although he sounded a few cautionary notes. Writing a big mainstream biography would mean a considerable shift in my career trajectory—up until that point, I had only published novels, short fiction, and essays—and it would take a lot of convincing to persuade a publisher that I was ready to take on this kind of project. At first, all of my energy was devoted to putting together a convincing proposal, which took about four months of work, during which I did much of the preliminary research and went through several rounds of feedback and rewrites. It wound up being about seventy pages long, and it was focused entirely on Campbell. We went out to a handful of publishers toward the end of the following January, and we got indications of interest from two editors. One was Julia Cheiffetz at Dey Street Books, an imprint of HarperCollins, who suggested that we “reframe” the book to bring in a few other famous writers, since Campbell wasn’t as well known in the mainstream. (She pointed specifically to Positively 4th Street: The Lives and Times of Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, Mimi Baez Fariña, and Richard Fariña by David Hajdu as one possible model.) I responded that I could expand the book to include Asimov, Heinlein, and Hubbard, and the notion was agreeable enough that I was able to announce the project on this blog on February 26, 2016.

Obviously, a lot has happened since then, both in my life and in everyone else’s. I couldn’t be happier with how the book turned out, but what strikes me the most now about the whole process is one line from that original email: “I’m starting to think that I might just be the guy to write it.” Looking back, I can’t for the life of me recall what inspired me to write that sentence, which in retrospect seems full of unwarranted confidence. About halfway through this book, I realized that there was a good reason why no biography of Campbell had ever been written. It’s just an incredibly complicated project, and working on it for nearly three years to the exclusion of everything else was barely enough to do it justice. When I look at the result, I’m very proud, but I also feel that it could easily have been much longer. (In fact, the first draft was twice as long as what ended up in print, and it wasn’t because I was padding it.) I didn’t have all the critical tools or the background that I needed when I started, and much of my recent life has been devoted to turning myself into the kind of person that it seemed to require. What I had in mind, basically, was a book that looked a certain way. It was sort of like Hajdu’s book, but also like a prestige literary biography along the lines of Adam Begley’s Updike, which is the kind of thing that I personally enjoy reading. This imposed certain expectations when it came to tone, size, and scholarship, and my ultimate goal was to end up something that wouldn’t look out of place on the same shelf—apart, perhaps, from the exploding space station on the cover. Along the way, I did the best impersonation that I could of the kind of person who could write such a book, and toward the end, I like to think that I more or less grew into the role. At every turn, I tried to ask myself: “What would a real biographer do?” And while I’m clearly the last person in the world who can be objective about this, I feel that the finished product reflects those standards.

Anyway, it’s out in the world now, and not surprisingly, I’ve been wondering endlessly about how it will be received—although it isn’t all that I have on my mind. This is still a terrible time, and there are moments when I can barely work up enough enthusiasm to care deeply about anything but what I see in the headlines. (When my publisher decided to push the release date back from August to October, part of me found it hard to believe that people would have the bandwidth to read about anything except the midterms, and I don’t think I was entirely wrong.) But I’m going to close this post with a direct appeal, and I promise that it’s the only time that I’ll ever say something like this, at least for this particular book. If you’ve enjoyed this blog or my writing in general, I’d encourage you to consider buying a copy of Astounding. I was lucky to have the chance to work on almost nothing else for the last three years, and I’d very much like to do it again. Whether or not that happens will hinge in large part on how well this book does. The more I think about Astounding, in fact, the more I feel that that it couldn’t have happened in any other way. It needed all the time and commitment that I was able to give it, and it also benefited from being released through a commercial publishing house, which subjected it to important pressures that obliged it to be more focused than it might have been if I had gone through an academic imprint. And it’s the better for it. Very few critical works on science fiction have been produced under such circumstances, but I also suspect, deep down, that this is how a book like this ought to be written. At least it’s the only way that I’ll ever be able to write one. If I’m ever going to do it again, enough people have to agree with me to the extent of paying for a copy. That’s only sales pitch that I have—except to say that if you’ve read this far, you’ll probably enjoy this book. And I’m grateful beyond words that I had the chance to do it even once.

The object of desire

Yesterday, I began to hear rumors that something was out in the world. My first clue was a congratulatory note from my agent in New York, who sent me an email with the subject line: “It’s a book!” The message itself was blank, except for a picture of his desk, on which he had propped up the hardcover of Astounding. A few hours later, I saw an editor for a pop culture site post the image of a stack of new books on Twitter, with mine prominently displayed about a third of the way from the bottom. In the meantime, there wasn’t any sign on it on my end—I hadn’t even seen the finished version yet. (I signed off on the last set of proofs months ago, and I’ve spent an inordinate amount of time admiring the cover art, but that isn’t quite the same as holding the real thing in your hands.) When the mail came that afternoon, there was nothing, so I figured that it would take another day or two for any shipment from my publisher’s warehouse to make it out to Chicago. In the evening, I headed out to the city, where I was meeting a few writers for dinner before our event at Volumes Bookcafe. When one of my friends arrived at the restaurant, he announced that he had heard a thud on his doorstep earlier that day, and he proudly pulled out his personal copy of the hardcover, from which he had prudently removed the dust jacket. At this point, I was starting to suspect that everybody in America would get it before I did, and when I arrived at the bookstore, I was genuinely shocked to see a table covered with copies of the book, which doesn’t officially come out until October 23. And although I should have been preparing for my reading, I took a minute to carry one into a quiet corner so that I could study it for myself.

Well, it definitely exists, and it’s just as beautiful as I had hoped. As a writer, I don’t have any control over the visual side, but the artist Tavis Coburn and the designers Ploy Siripant and Renata De Oliveira did a fantastic job—I’m obviously biased, but I don’t think any book about science fiction has ever come in a nicer package. The fact that I managed to get the hardcover version out into the world before physical books disappeared entirely is a source of real pride, and I look forward to seeing copies of it in thrift stores and cutout bins for years to come. And while I can’t speak to the contents, at first glance, they seemed perfectly fine, too. After the reading, which went well, I made my first sale of Astounding ever in a bookstore, and as I signed all the remaining copies that the store had on hand, I was sorely tempted to buy one for myself. I sent a picture of the stack on the display table to my wife, who texted back immediately: “Your copies came! One big box and one small one.” An hour or so later, I was back home, where I sliced open the first carton, then the second, to reveal my twenty-five author’s copies. (I’ll keep three for myself and gradually start to send the rest to various deserving recipients.) Now it’s the following morning, and the book is inexorably starting to assume the status of a familiar object. It’s lying at my elbow as I type this, and I can already feel myself taking it for granted. I suppose that was inevitable. But I’ll always treasure the memory of the day in which everyone I knew seemed to have it except for me.

The audio file

When you spend most of your working life typing in silence, it can be disorienting to hear your own words spoken out loud. Writers are often advised to read their writing aloud to check the rhythm, but I’ve never gotten into the habit, and I tend to be more obsessed with how the result looks on the page. As a result, whenever I encounter an audio version of something I’ve written, it feels disorienting, like hearing my own voice on tape. I vividly remember listening to StarShipSofa’s version of “The Boneless One,” narrated by Josh Roseman, while holding my newborn daughter in the hospital, and if everything goes as planned, another publisher will release an audio anthology that includes my novella “The Proving Ground”—which was recently named a notable story in the upcoming edition of The Best American Science Fiction and Fantasy—within the next couple of months. And the most memorable project of all was “Retention,” my episode of the science fiction audio series The Outer Reach, which was performed by Aparna Nancherla and Echo Kellum. I’ve never forgotten the result, but listening to it was such an emotionally charged experience that I’ve only managed to play it once. (Hearing the finished product was gratifying, but the process also cured me of any desire to write words for actors. It’s exciting when it happens, but also requires a degree of detachment that I don’t currently possess.)

I mention all this now because an excerpt of the audiobook version of Astounding has just been posted on SoundCloud. It’s about five minutes long, and it includes the opening section of the first chapter, which recounts a rather strange incident—involving drugs, mirrors, and hypnosis—from the partnership of John W. Campbell and L. Ron Hubbard in the early days of dianetics. The narrator is Sean Runnette, who certainly knows the territory, with previous credits that include Heinlein’s The Number of the Beast and the novel that was the basis for The Meg. He does a great job, and although I haven’t heard the rest, which comes to more than thirteen hours, I suspect that I’m going to end up playing all of it. One of the hardest parts of writing anything is putting enough distance between yourself and your work so that you can review it objectively. For a short story, I’ve found that a few weeks is long enough, but in the case of a novel, it can take months, or even longer. And I’m not remotely close to that point yet with this book. Listening to this audio sample, however, I finally felt as if it had been written by somebody else, as if the translation from one medium into another had yielded the same effect that I normally get from distance in time. (Which may be the real reason why reading your work out loud might be a good idea.) I’m glad that this audio version exists for a lot of reasons, but I’m especially grateful for the new perspective that it offers on this book, which I wrote largely because it was something that I wanted to read. And so far, I actually like it.

The purity test

Earlier this week, The New York Times Magazine published a profile by Taffy Brodesser-Akner of the novelist Jonathan Franzen. It’s full of fascinating moments, including a remarkable one that seems to have happened entirely by accident—the reporter was in the room when Frazen received a pair of phone calls, including one from Daniel Craig, to inform him that production had halted on the television adaptation of his novel Purity. Brodesser-Akner writes: “Franzen sat down and blinked a few times.” That sounds about right to me. And the paragraph that follows gets at something crucial about the writing life, in which the necessity of solitary work clashes with the pressure to put its fruits at the mercy of the market:

He should have known. He should have known that the bigger the production—the more people you involve, the more hands the thing goes through—the more likely that it will never see the light of day resembling the thing you set out to make in the first place. That’s the real problem with adaptation, even once you decide you’re all in. It just involves too many people. When he writes a book, he makes sure it’s intact from his original vision of it. He sends it to his editor, and he either makes the changes that are suggested or he doesn’t. The thing that we then see on shelves is exactly the thing he set out to make. That might be the only way to do this. Yes, writing a novel—you alone in a room with your own thoughts—might be the only way to get a maximal kind of satisfaction from your creative efforts. All the other ways can break your heart.

To be fair, Franzen’s status is an unusual one, and even successful novelists aren’t always in the position of taking for granted the publication of “exactly the thing he set out to make.” (In practice, it’s close to all or nothing. In my experience, the novel that you see on store shelves mostly reflects what the writer wanted, while the ones in which the vision clashes with those of other stakeholders in the process generally doesn’t get published at all.) And I don’t think I’m alone when I say that some of the most interesting details that Brodesser-Akner provides are financial. A certain decorum still surrounds the reporting of sales figures in the literary world, so there’s a certain frisson in seeing them laid out like this:

And, well, sales of his novels have decreased since The Corrections was published in 2001. That book, about a Midwestern family enduring personal crises, has sold 1.6 million copies to date. Freedom, which was called a “masterpiece” in the first paragraph of its New York Times review, has sold 1.15 million since it was published in 2010. And 2015’s Purity, his novel about a young woman’s search for her father and the story of that father and the people he knew, has sold only 255,476.

For most writers, selling a quarter of a million copies of any book would exceed their wildest dreams. Having written one of the greatest outliers of the last twenty years, Franzen simply reverting to a very exalted mean. But there’s still a lot to unpack here.

For one thing, while Purity was a commercial disappointment, it doesn’t seem to have been an unambiguous disaster. According to Publisher’s Weekly, its first printing—which is where you can see a publisher calibrating its expectations—came to around 350,000 copies, which wasn’t even the largest print run for that month. (That honor went to David Lagercrantz’s The Girl in the Spider’s Web, which had half a million copies, while a new novel by the likes of John Grisham can run to over a million.) I don’t know what Franzen was paid in advance, but the loss must have fallen well short of a book like Tom Wolfe’s Back to Blood, for which he received $7 million and sold 62,000 copies, meaning that his publisher paid over a hundred dollars for every copy that someone actually bought. And any financial hit would have been modest compared to the prestige of keeping a major novelist on one’s list, which is unquantifiable, but no less real. If there’s one thing that I’ve learned about publishing over the last decade, it’s that it’s a lot like the movie industry, in which apparently inexplicable commercial and marketing decisions are easier to understand when you consider their true audience. In many cases, when they buy or pass on a book, editors aren’t making decisions for readers, but for other editors, and they’re very conscious of what everyone in their imprint thinks. A readership is an abstraction, except when quantified in sales, but editors have their everyday judgement calls reflected back on them by the people they see every day. Giving up a writer like Franzen might make financial sense, but it would be devastating to Farrar, Straus and Giroux, to say nothing of the relationship that can grow between an editor and a prized author over time.

You find much the same dynamic in Hollywood, in which some decisions are utterly inexplicable until you see them as a manifestation of office politics. In theory, a film is made for moviegoers, but the reactions of the producer down the hall are far more concrete. The difference between publishing and the movies is that the latter publish their box office returns, often in real time, while book sales remain opaque even at the highest level. And it’s interesting to wonder how both industries might differ if their approaches were more similar. After years of work, the success of a movie can be determined by the Saturday morning after its release, while a book usually has a little more time. (The exception is when a highly anticipated title doesn’t make it onto the New York Times bestseller list, or falls off it with alarming speed. The list doesn’t disclose any sales figures, which means that success is relative, not absolute—and which may be a small part of the reason why writers seldom wish one another well.) In the absence of hard sales, writers establish the pecking order with awards, reviews, and the other signifiers that have allowed Franzen to assume what Brodesser-Akner calls the mantle of “the White Male Great American Literary Novelist.” But the real takeaway is how narrow a slice of the world this reflects. Even if we place the most generous interpretation imaginable onto Franzen’s numbers, it’s likely that well under one percent of the American population has bought or read any of his books. You’ll find roughly the same number on any given weeknight playing HQ Trivia. If we acknowledged this more widely, it might free writers to return to their proper cultural position, in which the difference between a bestseller and a disappointment fades rightly into irrelevance. Who knows? They might even be happier.

The invisible library

Over the last week, three significant events occurred in the timeline of my book Astounding. The page proofs—the typeset text to which the author can still make minor changes and corrections—were due back at my publisher on Wednesday. Yesterday, I received a boxful of uncorrected advance copies, which look great. And I got paid. This last point might not seem worth mentioning, but it’s an aspect of the process that doesn’t get the attention that it deserves. An advance payment for a book, which is often the only money that a writer ever sees, is usually delivered in three installments. (The breakdown depends on the terms of the contract, but it’s roughly divided into thirds, although the first chunk is generally a little larger than the others, and the middle one tends to be the smallest.) One piece is paid on signing; another on acceptance of the manuscript; and the last on publication. In practice, the payments can get held up for one reason or another, and in my case, nearly two and a half years passed between the first installment and the second. That’s a long time to stretch it out. And it points to one of the challenges of the publishing industry, which is that it’s survivable only by writers who have either an alternative source of income or a robust support structure. This naturally limits the kinds of voices and the range of subjects that it can accommodate. I don’t think that I could have written this book in under three years if I had been working a regular job, and the fact that I managed to pull it off at all was thanks to luck, good timing, and a very patient spouse.

But it also provided me with fresh insight into one of my great unanswered questions about this project, which was why no one had ever done it before. A biography of John W. Campbell seemed like such an obvious and necessary book that I was amazed to realize that it didn’t exist, and it was that moment of realization that inspired this whole enterprise. If anything like it had been attempted in the past, even in an obscure academic publication, I don’t think I would have tackled it in the first place. One explanation for its absence is that the best time for such a book would have been in the late seventies, when such writers as Isaac Asimov and Frederik Pohl were publishing their memoirs, and by the time various obstacles had been sorted out, its moment had come and gone. And it’s also true that Campbell’s life presents particular challenges that might dissuade potential biographers. It would have been a tough project for anyone, and one of my advantages may have been that I underestimated the difficulties that it would present. But the simple fact, as I’ve come to appreciate, is that the odds are against any book seeing the light of day. This one hinged on a combination of factors so unlikely that I have trouble believing it myself, and if just one of those pieces had failed to fall into place, it never would have happened. Maybe someone else would have tried again a decade from now, but I’m not sure. If it seems inevitable to me now, that’s another reason to reflect on the many books that have yet to be written. (Even within the field of science fiction, there are staggering omissions. There’s no biography or study of Leigh Brackett, for instance, and I strongly encourage someone else to pitch it before I do.) This book exists, which is a miracle in itself. But for every book that sees print, there’s an invisible library of unwritten—and equally worthy—books behind it.

Checks and balances

About a third of the way through my upcoming book, while discussing the May 1941 issue of Astounding Science Fiction, I include the sentence: “The issue also featured Heinlein’s “Universe,” which was based on Campbell’s premise about a lost generation starship.” My copy editor amended this to “a lost-generation starship,” to which I replied: “This isn’t a ‘lost-generation’ starship, but a generation starship that happens to be lost.” And the exchange gave me a pretty good idea for a story that I’ll probably never write. (I don’t really have a plot for it yet, but it would be about Hemingway and Fitzgerald on a trip to Alpha Centauri, and it would be called The Double Sun Also Rises.) But it also reminded me of one of the benefits of a copy edit, which is its unparalleled combination of intense scrutiny and total detachment. I sent drafts of the manuscript to some of the world’s greatest nitpickers, who saved me from horrendous mistakes, and the result wouldn’t be nearly as good without their advice. But there’s also something to be said for engaging the services of a diligent reader who doesn’t have any connection to the subject. I deliberately sought out feedback from a few people who weren’t science fiction fans, just to make sure that it remained accessible to a wider audience. And the ultimate example is the copy editor, who is retained to provide an impartial consideration of every semicolon without any preconceived notions outside the text. It’s what Heinlein might have had in mind when he invented the Fair Witness, who said when asked about the color of a nearby house: “It’s white on this side.”

But copy editors are human beings, not machines, and they occasionally get their moment in the spotlight. Recently, their primary platform has been The New Yorker, which has been quietly highlighting the work of its copy editors and fact checkers over the last few years. We can trace this tendency back to Between You & Me, a memoir by Mary Norris that drew overdue attention to the craft of copy editing. In “Holy Writ,” a delightful excerpt in the magazine, Norris writes of the supposed objectivity and rigor of her profession: “The popular image of the copy editor is of someone who favors rigid consistency. I don’t usually think of myself that way. But, when pressed, I do find I have strong views about commas.” And she says of their famous detachment:

There is a fancy word for “going beyond your province”: “ultracrepidate.” So much of copy editing is about not going beyond your province. Anti-ultracrepidationism. Writers might think we’re applying rules and sticking it to their prose in order to make it fit some standard, but just as often we’re backing off, making exceptions, or at least trying to find a balance between doing too much and doing too little. A lot of the decisions you have to make as a copy editor are subjective. For instance, an issue that comes up all the time, whether to use “that” or “which,” depends on what the writer means. It’s interpretive, not mechanical—though the answer often boils down to an implicit understanding of commas.

In order to be truly objective, in other words, you have to be a little subjective. Which equally true of writing as a whole.

You could say much the same of the fact checker, who resembles the copy editor’s equally obsessive cousin. As a rule, books aren’t fact-checked, which is a point that we only seem to remember when the system breaks down. (Astounding was given a legal read, but I was mostly on my own when it came to everything else, and I’m grateful that some of the most potentially contentious material—about L. Ron Hubbard’s writing career—drew on an earlier article that was brilliantly checked by Matthew Giles of Longreads.) As John McPhee recently wrote of the profession:

Any error is everlasting. As Sara [Lippincott] told the journalism students, once an error gets into print it “will live on and on in libraries carefully catalogued, scrupulously indexed…silicon-chipped, deceiving researcher after researcher down through the ages, all of whom will make new errors on the strength of the original errors, and so on and on into an exponential explosion of errata.” With drawn sword, the fact-checker stands at the near end of this bridge. It is, in part, why the job exists and why, in Sara’s words, a publication will believe in “turning a pack of professional skeptics loose on its own galley proofs.”

McPhee continues: “Book publishers prefer to regard fact-checking as the responsibility of authors, which, contractually, comes down to a simple matter of who doesn’t pay for what. If material that has appeared in a fact-checked magazine reappears in a book, the author is not the only beneficiary of the checker’s work. The book publisher has won a free ticket to factual respectability.” And its absence from the publishing process feels like an odd evolutionary vestige of the book industry that ought to be fixed.

As a result of such tributes, the copy editors and fact checkers of The New Yorker have become cultural icons in themselves, and when an error does make it through, it can be mildly shocking. (Last month, the original version of a review by Adam Gopnik casually stated that Andrew Lloyd Webber was the composer of Chess, and although I knew perfectly well that this was wrong, I had to look it up to make sure that I hadn’t strayed over into a parallel universe.) And their emergence at this particular moment may not be an accident. The first installment of “Holy Writ” appeared on February 23, 2015, just a few months before Donald Trump announced that he was running for president, plunging us all into world in which good grammar and factual accuracy can seem less like matters of common decency than obstacles to be obliterated. Even though the timing was a coincidence, it’s tempting to read our growing appreciation for these unsung heroes as a statement about the importance of the truth itself. As Alyssa Rosenberg writes in the Washington Post:

It’s not surprising that one of the persistent jokes from the Trump era is the suggestion that we’re living in a bad piece of fiction…Pretending we’re all minor characters in a work of fiction can be a way of distancing ourselves from the seeming horror of our time or emphasizing our own feelings of powerlessness, and pointing to “the writers” often helps us deny any responsibility we may have for Trump, whether as voters or as journalists who covered the election. But whatever else we’re doing when we joke about Trump and the swirl of chaos around him as fiction, we’re expressing a wish that this moment will resolve in a narratively and morally comprehensible fashion.

Perhaps we’re also hoping that reality itself will have a fact checker after all, and that the result will make a difference. We don’t know if it will yet. But I’m hopeful that we’ll survive the exponential explosion of errata.

Changing the future

Astounding: John W. Campbell, Isaac Asimov, Robert A. Heinlein, L. Ron Hubbard, and the Golden Age of Science Fiction is now scheduled to be released on October 23, 2018. It was originally slated for August 14, but my publisher recently raised the possibility of pushing it back, and we agreed on the new date earlier this week. Why the change? Well, it’s a good thing. This is a big book—by one estimate, we’re looking at close to five hundred pages, including endnotes, back matter, and index—and it needs time to be edited, typeset, and put into production. We could also use the extra nine weeks to get it into bookstores and into the hands of reviewers, and rescheduling it for the fall puts us in a better position. The one downside, at least from my point of view, is that now we’ll be coming out in a corridor that is always packed with major releases, and it’s going to be challenging for us to stand out. (It’s also just two weeks before the midterm elections, and I’m worried about how much bandwidth readers will have to think about anything else.) But everybody involved seems to think that we can handle it, and I have no reason to doubt their enthusiasm or expertise.

In short, if you’ve been looking forward to reading Astounding, you’ll have to wait two months longer. (Apart from an upcoming round of minor edits, by the way, the book is basically finished.) In the meantime, at the end of this month, I’m attending the academic conference “Grappling With the Futures” at Harvard and Boston University, where I’ll be delivering a presentation on the evolution of psychohistory alongside the scholar Emmanuelle Burton. The July/August issue of Analog will feature “The Campbell Machine,” a modified excerpt from the book, including a lot of material that won’t appear anywhere else, about one of the most significant incidents in John W. Campbell’s life—the tragic death of his stepson, which encouraged his interest in psionics and culminated in his support of the Hieronymus Machine. And I’m hopeful that a piece about Campbell’s role in the development of dianetics will appear elsewhere in the fall. I’ve also confirmed that I’ll be a program participant at the upcoming World Science Fiction Convention in San Jose, which runs from August 16 to 20. At one point, I’d planned to have the book in stores by then, which isn’t quite how it worked out. But if you run into me there, ask me for a copy. If I have one handy, it’s yours.

Looking for “The Spires”

Over two years ago, I was browsing at my local thrift store when my eye was caught by a book titled Alaska Bush Pilots in the Float Country. Its dust jacket read: “The men who brought airplanes to Alaska’s Panhandle were a different breed: a little braver than the average pilot and blessed with the particular skills and set of nerves it requires to fly float planes, those Lockheed Vegas made of plywood that were held together by termites holding hands, as well as the sturdy Fairchild 71s and Bellanca Pacemakers.” This might not seem like a volume that would appeal to the average reader, but I bought it—and I had a particular use for it in mind. Like most writers, I’m constantly on the lookout for promising veins of material, and my inner spidey sense began to tingle as soon as I saw that cover. If I had to describe the kind of short stories that I like to write, I’d call them carefully plotted works of science fiction, usually staged against a colorful backdrop, often with elements of horror. The Alaskan Panhandle in the thirties seemed like as good a setting for this as any, and that book on bush pilots was visibly packed with more information than I would need for a novelette. I’ve come to treasure works of nonfiction that provide a narrow but deep slice of knowledge about a previously unexplored topic, and I automatically got to thinking about bush pilots in Alaska, even though the subject had never interested me before.

It took me over a year to get to it, but the result was my novelette “The Spires,” which appears in the current issue of Analog Science Fiction and Fact. It was the first story that I’d attempted since commencing work on Astounding, and it was more informed than usual by the history of science fiction. When I sat down to think about it in earnest, I decided more or less at random to approach it as a tribute to the work of Charles Fort, who filled four large books with accounts of unexplained events that he gleaned from the newspaper archives at the New York Public Library. In New Lands, Fort mentions a phantom city that has occasionally been seen in the sky over Alaska, which seemed like an excellent place to start. My goal, as usual, was to begin with what sounded like a paranormal phenomenon and work backward to a scientific explanation that wouldn’t be out of place in Analog, sort of like The X-Files in reverse. I’m still not entirely sure what to think of the result here—and I resisted it for a long time. It comes perilously close to a shaggy dog story, but I like the atmosphere, and the “solution,” while not one that I would have chosen under most circumstances, ended up feeling inevitable. If you read it, I hope you’ll agree. In a few weeks, I’ll talk about its origins at length, but in the meantime, I’ll leave you with one of my favorite quotes from Fort: “My own notion is that it is very unsportsmanlike ever to mention fraud. Accept anything. Then explain it your way.”

This post has no title

In John McPhee’s excellent new book on writing, Draft No. 4, which I mentioned here the other day, he shares an anecdote about his famous profile of the basketball player Bill Bradley. McPhee was going over a draft with William Shawn, the editor of The New Yorker, “talking three-two zones, blind passes, reverse pivots, and the setting of picks,” when he realized that he had overlooked something important:

For some reason—nerves, what else?—I had forgotten to find a title before submitting the piece. Editors of every ilk seem to think that titles are their prerogative—that they can buy a piece, cut the title off the top, and lay on one of their own. When I was young, this turned my skin pink and caused horripilation. I should add that I encountered such editors almost wholly at magazines other than The New Yorker—Vogue, Holiday, the Saturday Evening Post. The title is an integral part of a piece of writing, and one of the most important parts, and ought not to be written by anyone but the writer of what follows the title. Editors’ habit of replacing an author’s title with one of their own is like a photo of a tourist’s head on the cardboard body of Mao Zedong. But the title missing on the Bill Bradley piece was my oversight. I put no title on the manuscript. Shawn did. He hunted around in the text and found six words spoken by the subject, and when I saw the first New Yorker proof the piece was called “A Sense of Where You Are.”

The dynamic that McPhee describes at other publications still exists today—I’ve occasionally bristled at the titles that have appeared over the articles that I’ve written, which is a small part of the reason that I’ve moved most of my nonfiction onto this blog. (The freelance market also isn’t what it used to be, but that’s a subject for another post.) But a more insidious factor has invaded even the august halls of The New Yorker, and it has nothing to do with the preferences of any particular editor. Opening the most recent issue, for instance, I see that there’s an article by Jia Tolentino titled “Safer Spaces.” On the magazine’s website, it becomes “Is There a Smarter Way to Think About Sexual Assault on Campus?”, with a line at the bottom noting that it appears in the print edition under its alternate title. Joshua Rothman’s “Jambusters” becomes “Why Paper Jams Persist.” A huge piece by David Grann, “The White Darkness,” which seems destined to get optioned for the movies, earns slightly more privileged treatment, and it merely turns into “The White Darkness: A Journey Across Antarctica.” But that’s the exception. When I go back to the previous issue, I find that the same pattern holds true. Michael Chabon’s “The Recipe for Life” is spared, but David Owen’s “The Happiness Button” is retitled “Customer Satisfaction at the Push of a Button,” Rachel Aviv’s “The Death Debate” becomes “What Does It Mean to Die?”, and Ian Frazier’s “Airborne” becomes “The Trippy, High-Speed World of Drone Racing.” Which suggests to me that if McPhee’s piece appeared online today, it would be titled something like “Basketball Player Bill Bradley’s Sense of Where He Is.” And that’s if he were lucky.

The reasoning here isn’t a mystery. Headlines are written these days to maximize clicks and shares, and The New Yorker isn’t immune, even if it sometimes raises an eyebrow. Back in 2014, Maria Konnikova wrote an article for the magazine’s website titled “The Six Things That Make Stories Go Viral Will Amaze, and Maybe Infuriate, You,” in which she explained one aspect of the formula for online headlines: “The presence of a memory-inducing trigger is also important. We share what we’re thinking about—and we think about the things we can remember.” Viral headlines can’t be allusive, make a clever play on words, or depend on an evocative reference—they have to spell everything out. (To build on McPhee’s analogy, it’s less like a tourist’s face on the cardboard body of Mao Zedong than an oversized foam head of Mao himself.) A year later, The New Yorker ran an article by Andrew Marantz on the virality expert Emerson Spartz, and it amazed and maybe infuriated me. I’ve written about this profile elsewhere, but looking it over again now, my eye was caught by these lines:

Much of the company’s success online can be attributed to a proprietary algorithm that it has developed for “headline testing”—a practice that has become standard in the virality industry…Spartz’s algorithm measures which headline is attracting clicks most quickly, and after a few hours, when a statistically significant threshold is reached, the “winning” headline automatically supplants all others. “I’m really, really good at writing headlines,” he told me.

And it’s worth noting that while Marantz’s piece appeared in print as “The Virologist,” in an online search, it pops up as “King of Clickbait.” Even as the magazine gently mocked Spartz, it took his example to heart.

None of this is exactly scandalous, but when you think of a title as “an integral part of a piece of writing,” as McPhee does, it’s undeniably sad. There isn’t any one title for an article anymore, and most readers will probably only see its online incarnation. And this isn’t because of an editor’s tastes, but the result of an impersonal set of assumptions imposed on the entire industry. Emerson Spartz got his revenge on The New Yorker—he effectively ended up writing its headlines. And while I can’t blame any media company for doing whatever it can to stay viable, it’s also a real loss. McPhee is right when he says that selecting a title is an important part of the process, and in a perfect world, it would be left up to the writer. (It can even lead to valuable insights in itself. When I was working on my article on the fiction of L. Ron Hubbard, I was casting about randomly for a title when I came up with “Xenu’s Paradox.” I didn’t know what it meant, but it led me to start thinking about the paradoxical aspects of Hubbard’s career, and the result was a line of argument that ended up being integral not just to the article, but to the ensuing book. And I was amazed when it survived intact on Longreads.) When you look at the grindingly literal, unpoetic headlines that currently populate the homepage of The New Yorker, it’s hard not to feel nostalgic for an era in which an editor might nudge a title in the opposite direction. In 1966, when McPhee delivered a long piece on oranges in Florida, William Shawn read it over, focused on a quotation from the poet Andrew Marvell, and called it “Golden Lamps in a Green Night.” McPhee protested, and the article was finally published under the title that he had originally wanted. It was called “Oranges.”

Advertising the future

Note: I’m taking a few days off for the holidays, so I’ll be republishing some of my favorite pieces from earlier in this blog’s run. This post originally appeared, in a slightly different form, on September 8, 2016.

In 1948, the editor John W. Campbell made an announcement that would alter the course of science fiction forever. (If you’re guessing that it had something to do with dianetics, you’re close, but about a year and a half too early.) Here’s what he wrote in the April issue of Astounding:

For the first time, advertising space in Astounding Science Fiction alone is being sold—a departure from the previous policy of selling only space in the Street & Smith fiction group. To readers, this should mean ads of real service and interest, directed to you and your interests. To the advertisers, this opens a new specialized medium. To publishers of technical and science-fiction books in particular, it should be welcome news.

The next month, in the issue in which the first targeted ads appeared, Campbell expanded on the reasoning behind the change:

Normally, in a general-circulation magazine, ads tend to be simply a space-waster from the reader’s viewpoint; in the past, to a considerable extent, I fear that they have been so in Astounding. In special-group magazines, however, advertisements properly selected for that special group serve a definite and useful purpose to both reader and advertiser…In the present issue there are several ads for science-fiction and fantasy books that you might not have heard of, or might have forgotten, books that you’ll be interested in knowing about, because they are of interest to your particular field of interest. Such ads serve as bulletin boards to keep you aware of what’s happening in this field.

It was a seemingly minor development, but it transformed the genre profoundly, to an extent that I don’t think anyone realized at the time. Advertising had been an important part of the magazine from the beginning, of course: the first issue of Astounding Stories of Super-Science had a full twenty pages of ads—a bounty that seems unbelievable today, when Analog can struggle to land even one or two full-page ads on an average month. Readers of the golden age would have quickly become familiar with brands like Listerine, Charles Atlas, International Correspondence Schools, Camel cigarettes, and Calvert whiskey, and these ads still lend their yellowing pages a certain nostalgic appeal. But they didn’t have much to do with science fiction, and Campbell grew increasingly frustrated with this fact, especially as the genre began to make real incursions into the mainstream. On a number of occasions, he used his own precious editorial space to promote the anthologies, like The Best of Science Fiction and Adventures in Time and Space, that were finally appearing in bookstores, and when targeted ads made their debut at last, it must have seemed like a revolution that had taken place overnight. There were announcements of hardcover editions of Final Blackout by L. Ron Hubbard and The World of Null-A by A.E. van Vogt, along with an invitation to write for catalogs from Arkham House and Fantasy Focus. These publishers already existed before the change in policy, but there’s no question that they benefited from it. Two years later, much the same was true of the book Dianetics: The Modern Science of Mental Health, which never would have reached the audience that it did without targeted advertising.

And it’s hard to overstate the impact that this had on science fiction. After World War II, the genre had made a dramatic push into the wider culture: the atomic bomb had radically increased interest in science fiction as a literature of prediction, and Campbell himself became something of a celebrity, giving interviews to The New Yorker and The Wall Street Journal and signing a contact with Henry Holt to write The Atomic Story. Over the following years, circulation spiked to the point where newsstands had trouble keeping magazines in stock, and movies like Destination Moon, based on a story by Robert A. Heinlein, led the new wave of science fiction in film, as Dimension X did on radio. Science fiction also began to appear widely in book form for the first time, not only in anthologies and reprints, but in original novels like the Heinlein juveniles and Asimov’s Pebble in the Sky. And the option of advertising directly to the readers of magazines like Astounding was an essential cog in the machine, since it meant that science fiction fans could be seen as a distinct demographic. The following year, Campbell conducted a reader survey for the benefit of advertisers, and the results were very revealing. Not surprisingly, 93.3 percent of the respondents were male. The median age was just under thirty, most had college degrees, and the average salary was over four hundred dollars a month, placing them comfortably in the middle class. It was clearly worth investing in an audience like this: Campbell cheerfully noted that booksellers were expanding their ad purchases in response to reader demand, and circulation was at 100,000 and climbing.

But it was an end as much as it was a beginning. Fandom had formed a vibrant community since the early thirties, even if it was often torn by petty rivalries, but it’s one thing to define a group on its own terms, and quite another to have it targeted by advertisers. Today, science fiction and fantasy fans have become such a key demographic that we don’t even think of them as a separate market: it’s the cultural baseline for anyone under thirty. There’s a tremendous incentive to reach those consumers, and those early ads were a faint glimmer of the momentous developments to come. Looking back, in fact, the change in ad policy seems to mark the moment at which science fiction became too large for any one man to control. Within a year or two, The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction and Galaxy would be giving Campbell his first real competition, and more talent would be channeled into hardcover and paperback. Campbell was essentially given one last chance to leverage his power and influence over readers into something in the real world, and he chose to stake everything on dianetics, with unfortunate results. (Even that was a lucky accident of timing: Dianetics, the book, appeared after targeted advertising allowed it to maximize its impact on readers, at a time when interest in science fiction was at its peak, and before Campbell’s hold over the field had diminished. A few years earlier or later, and it might not have made remotely the same impression.) Astounding didn’t always succeed in predicting the future, but it did manage to discover—or create—a new kind of reader, as if it were terraforming a new planet. And it wasn’t long before it was colonized by the advertisers.

A lump of darkness

I’ve spent the last few days leafing with interest through the new second volume of the collected work of the graphic artist Chip Kidd, whose portfolio includes iconic covers for such books as Jurassic Park, The Secret History, and seemingly half of the prestige titles of the last thirty years. Kidd is the closest thing that we have to a celebrity book designer—he’s certainly the only one whom even a fraction of readers would be able to name—and his credit on the inside flap of a dust jacket remains one of three surefire indications that an author has made it. (The others are a headshot taken by Marion Ettlinger and an interview with The Paris Review.) He’s undeniably a major talent, even if the covers from the back half of his career don’t stand out as strongly from the pack as his earlier work, in part because his innovations and style have been absorbed into what people expect from a particular kind of hardcover. Kidd’s fondness for vintage art, his use of miniature photography, and his knack for visual paradox have all turned into shorthand signifiers of a certain level of class, and you could make a similar case for Kidd himself, who, not coincidentally, worked with Lisa Birnbach on a new edition of The Official Preppy Handbook. I don’t know how much he earns these days for an average commission, but I doubt that it’s dramatically higher in absolute terms than it is for many other designers, and it can’t be more than a modest fraction of the overall cost of producing a book. Kidd’s imprimatur has become an economical way for publishers to assure authors that they’re special, without having to spend a lot of money on the advance or the marketing budget, even if they’re positively correlated in practice. There’s also a feedback cycle at work, as Kidd is associated with the best books because of his longtime association with top authors, and he remains the first name likely to come to mind when a publisher is trying to project confidence in a title.

Which doesn’t mean that all of his ideas are automatically accepted. Browsing through Chip Kidd: Book Two, one of the first things that you notice is how many of his designs were rejected, sometimes on the way to a successful solution, but occasionally ending in a kill fee. A note of regret often slips through, as with it does with Elmore Leonard’s Djibouti: “My role in the project pretty much ended there; sad, because we had done so much great work in the past on his previous titles.” He sometimes pointedly employs the passive voice: “It was decided in-house that we should follow the design scheme of the previous book.” “It was determined that we needed [Obama’s] face.” “It was taken out of my hands and further abstracted.” “The approach, sadly, was nipped in the bud.” Kidd’s favorite clients are mentioned warmly by name, while a writer who didn’t like his cover designs becomes “the author.” He has a poor track record with HarperCollins, which nixed his initial designs for The Yiddish Policeman’s Union and the paperback reissue of The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay. Even John Updike, with whom Kidd had a long and productive relationship, killed the original cover—with lettering by Chris Ware—for My Father’s Tears: “Doesn’t this jacket strike you as, well, kind of wimpy?” Perhaps Kidd’s harshest words are reserved for the cover of You Better Not Cry by Augusten Burroughs, of which he recalls of a few failed attempts:

The answer was either to start over or bail. I couldn’t bear the thought of the latter…Somehow even this [last] image wasn’t blowing everyone’s dress up, and the plug was pulled. The dreaded kill fee. Adding insult to injury was what they finally came up with. You’ll have to google it, and you won’t believe it.

My point here is that even Chip Kidd, of all people, doesn’t have final say over how a book will eventually appear, and that’s doubly true of authors. Kidd hints that “third-rate writers are the hardest to work with because they subconsciously want the jacket to make up for the mediocrity of their work,” but it can be difficult for even a writer at the top of his craft to force through a difficult cover. The Tunnel by the late William H. Gass, for instance, might well be the least commercial novel ever put out by a major publishing house, and it required a huge leap of faith from Knopf. Gass, who died last week, wrote up a memo with his specifications for its design, and it makes for fascinating reading. Here’s a short section:

The book should be bound in rough black cloth. The spine should be broad and flat the way Viking Press’s edition of James Joyce’s Letters is, or Finnegans Wake. The title of the book, THE TUNNEL, should appear at the top left edge of the spine, indented, in silver…My name may have to go on the jacket and if so it should appear on the bottom of the spine up and down like the title and on the opposite or inner side of the spine panel. Otherwise there should be nothing on the book’s cover or dust jacket. It should be completely empty and dark like outer space or the inside of a cave. The reader should be holding a heavy really richly textured lump of darkness. The book’s size should be larger than normal. Again, the size of Finnegans Wake seems about right. It is important that my name appear nowhere on dust jacket or cover, and that nothing else be put on the jacket—no bio, picture, blurb, etc. The publisher will no doubt want their name on the book so it might be embossed at the bottom of the spine (but left black) and printed in silver at the bottom of the spine of the jacket.

This went over about as well as you might expect, and the result doesn’t look much like what Gass wanted. The interior of the book, by contrast, is beautifully designed and faithful to his vision, which implies that Knopf’s uneasiness about the cover was more about not totally crippling a novel that was already going to be a hard sell to most readers. It didn’t exactly work, as we read in Gass’s obituary in the New York Times: “Mr. Gass was one of the most respected authors never to write a bestseller.” But perhaps the lesson here is that the cover of a book, which is one of the few places where something like control seems like it ought to be possible, is just as much the product of compromise as anything else in publishing. (One of Kidd’s most memorable anecdotes involves the cover of Haruki Murakami’s novel 1Q84, which the printer initially refused even to produce, since it couldn’t guarantee that all of the elements would properly line up. They eventually negotiated a slippage factor of a quarter of an inch, and the book’s design was robust enough to look good even when the alignment was off—which feels like a metaphor for something.) And it may simply be that The Tunnel came out twenty years too soon. As I tweeted yesterday, it certainly seems like the novel of our time, as when its narrator writes of Hitler, whom he calls a “twerp”:

What I wonder about are all of those who weren’t twerps who willed what Hitler wished…they, who idolized a loud doll, who loved the twerps-truths, who carried out the wishes of a murderous fool, an ignoble nobody, a failure so unimportant that failure seems a fulsome description of him.

He concludes: “I would have followed him just to get even.” It might be time for a new edition. And Kidd would probably be the one to design it.