Posts Tagged ‘The Economist’

Ringing in the new

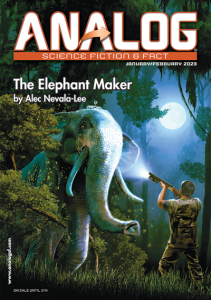

By any measure, I had a pretty productive year as a writer. My book Inventor of the Future: The Visionary Life of Buckminster Fuller was released after more than three years of work, and the reception so far has been very encouraging—it was named a New York Times Book Review Editors’ Choice, an Economist best book of the year, and, wildest of all, one of Esquire‘s fifty best biographies of all time. (My own vote would go to David Thomson’s Rosebud, his fantastically provocative biography of Orson Welles.) On the nonfiction front, I rounded out the year with pieces in Slate (on the misleading claim that Fuller somehow anticipated the principles of cryptocurrency) and the New York Times (on the remarkable British writer R.C. Sherriff and his wonderful novel The Hopkins Manuscript). Best of all, the latest issue of Analog features my 36,000-word novella “The Elephant Maker,” a revised and updated version of an unpublished novel that I started writing in my twenties. Seeing it in print, along with Inventor of the Future, feels like the end of an era for me, and I’m not sure what the next chapter will bring. But once I know, you’ll hear about it here first.

A Geodesic Life

After three years of work—and more than a few twists and turns—my latest book, Inventor of the Future: The Visionary Life of Buckminster Fuller, is finally here. I think it’s the best thing that I’ve ever done, or at least the one book that I’m proudest to have written. After last week’s writeup in The Economist, a nice review ran this morning in the New York Times, which is a dream come true, and you can check out excerpts today at Fast Company and Slate. (At least one more should be running this weekend in The Daily Beast.) If you want to hear more about it from me, I’m doing a virtual event today sponsored by the Buckminster Fuller Institute, and on Saturday August 13, I’ll be holding a discussion at the Oak Park Public Library with Sarah Holian of the Frank Lloyd Wright Trust, which will be also be available to view online. There’s a lot more to say here, and I expect to keep talking about Fuller for the rest of my life, but for now, I’m just delighted and relieved to see it out in the world at last.

A choice of categories

A few weeks ago, The Economist published a short article with the intriguing headline “Michel Foucault’s Lessons for Business.” It’s fun to speculate what the corporate world might actually stand to learn from this particular philosopher, who once noted that the capitalist system severely punishes crimes of property while discreetly reserving for itself “the illegality of rights.” In fact, the article is mostly interested in Foucault’s book The Order of Things, in which he examines the unstated assumptions that affect how we divide the universe into categories. The uncredited author begins:

Foucault was obsessed with taxonomies, or how humans split the world into arbitrary mental categories in order “to tame the wild profusion of existing things.” When we flip these around, “we apprehend in one great leap…the exotic charm of another system of thought.” Imagine, for example, a supermarket organized by products’ vintage. Lettuces, haddock, custard and the New York Times would be grouped in an aisle called “items produced yesterday.” Scotch, string, cans of dog food and the discounted Celine Dion DVDs would be in the “made in 2008” aisle.

And the article argues that we should take a closer look at how companies define themselves—how mining firms, for instance, are organized by commodity type, when a geographical analysis would reveal “that their production is often in unstable countries,” and that many of them are inordinately dependent on demand from China.

Speaking of China, Foucault’s interest in such problems had an unexpected inspiration, as he reveals in the preface to The Order of Things:

This book first arose out of a passage in [Jorge Luis] Borges, out of the laughter that shattered, as I read the passage, all the familiar landmarks of my thought—our thought that bears the stamp of our age and our geography—breaking up all the ordered surfaces and all the planes with which we are accustomed to tame the wild profusion of existing things, and continuing long afterwards to disturb and threaten with collapse our age-old distinction between the Same and the Other. This passage quotes a “certain Chinese encyclopedia” in which it is written that “animals are divided into: (a) belonging to the Emperor, (b) embalmed, (c) tame, (d) suckling pigs, (e) sirens, (f) fabulous, (g) stray dogs, (h) included in the present classification, (i) frenzied, (j) innumerable, (k) drawn with a very fine camel-hair brush, (l) et cetera, (m) having just broken the water pitcher, (n) that from a long way off look like flies.” In the wonderment of this taxonomy, the thing we apprehend in one great leap, the thing that, by means of the fable, is demonstrated as the exotic charm of another system of thought, is the limitation of our own, the stark impossibility of thinking that.”

Critics have tried in vain to find the source that Borges was using, if one even existed—although it’s worth noting that Foucault never explicitly affirms that the encyclopedia is real. (Borges attributes it to the German sinologist Franz Kuhn, and it would be a pretty problem for a bright scholar to track down a possible original.)

But you don’t need to resort to fiction to find taxonomies that call all your usual assumptions into question. Recently, while revisiting Buckminster Fuller’s book Critical Path, I was struck by a list of resources that he generated for the World Game, an educational simulation that he devised to encourage ecological thinking:

- Reliably operative and subconsciously sustaining [resources], effectively available twenty-four hours a day, anywhere in the Universe: gravity, love.

- Available only within ten miles of the surface of the Earth in sufficient quantity to conduct sound: i.e., the complex of atmospheric gases whose Sun-induced expansion on the sunny side and shadow-side-of-the-world induced contraction together produce the world’s winds, which in turn produce all the world’s waves.

- Available in sufficient quantity to sustain human life only within two miles above planet Earth’s spherical surface: oxygen.

- Available aboard our planet only during day: sunlight.

- Not everywhere or everywhere available: water, food, clothing, shelter, vision, initiative, friendliness.

- Only partially available for individual human consumption, being also required for industrial production: e.g., water.

- Not publicly available because used entirely by industry, e.g., helium.

- Not available to industry because used entirely by scientific laboratories: e.g., moon rocks.

You can chalk some of this up to Fuller’s simple weirdness, which is inseparable from his genius, but there’s also something undeniably useful about classifying resources by availability, which isn’t far removed from the hypothetical grocery store proposed by The Economist. It’s also revealing that so many of these schemes center on problems of resource allocation, since the categories that we use in practice often amount to a way of tracking the distribution of some finite benefit, material or otherwise. Our cultural debates, in particular, frequently depend on how we position ourselves within the patterns of give and take between groups. (The question of whether someone like Bruno Mars can be guilty of cultural appropriation is either mildly irritating or curiously profound, depending on how you look at it.) And while the classifications of Fuller or Borges’s apocryphal encyclopedist can seem amusingly random, they’re no less arbitrary than others that have evolved over time for practical reasons. If you were designing a political platform from scratch, it might seem absurd to lump together gun rights, opposition to abortion, support of the death penalty, a hard line on immigration, tax cuts, and climate change skepticism, or—in the case of both parties—to want the government to keep out of certain private matters while involving itself deeply in others. These methods of slicing up the world exist to hold together unstable coalitions, or to serve powerful interest groups, and we’ve seen how fragile certain convictions, such as a belief in free markets, can really be. Much of the trauma of this political moment has arisen from the splintering of established categories, or a sudden clarification of which parts truly mattered. The process is bound to continue until we arrive at a point of temporarily stability, which will inevitably find itself shaken apart in the next convulsion. As Borges concludes: “There is no classification of the universe that is not arbitrary and speculative. The reason is quite simple: we do not know what the universe is.”

Parkinson’s Law and the creative hour

In the November 19, 1955 issue of The Economist, the historian Cyril Northcote Parkinson stated the law that has borne his name ever since, in a paragraph remarkable for its sheer Englishness:

It is a commonplace observation that work expands so as to fill the time available for its completion. Thus, an elderly lady of leisure can spend the entire day in writing and dispatching a postcard to her niece at Bognor Regis. An hour will be spent in finding the postcard, another in hunting for spectacles, half an hour in a search for the address, an hour and a quarter in composition, and twenty minutes in deciding whether or not to take an umbrella when going to the pillar box in the next street. The total effort which would occupy a busy man for three minutes all told may in this fashion leave another person prostrate after a day of doubt, anxiety and toil.

Parkinson’s observation was originally designed to account for the unchecked growth of bureaucracy, which hinges on the fact that paperwork is “elastic in its demands on time”—and, by extension, on manpower. And he concluded the essay by stating, rather disingenuously, that it was only an empirical observation, without any value attached: “The discovery of this formula and of the general principles upon which it is based has, of course, no emotive value…Parkinson’s Law is a purely scientific discovery, inapplicable except in theory to the politics of the day. It is not the business of the botanist to eradicate the weeds. Enough for him if he can tell us just how fast they grow.”

In fact, Parkinson’s Law can be a neutral factor, or even a positive one, when it comes to certain forms of creativity. We can begin with one of its most famous, if disguised, variations, in the form of Blinn’s Law: “As technology advances, rendering time remains constant.” As I’ve noted before, once an animator gets used to waiting a certain number of hours for an image to render, as the hardware improves, instead of using it to save time, he just renders more complex graphics. There seems to be a fixed amount of time that any given person is willing to work, so an increase in efficiency doesn’t necessarily reduce the time spent at your desk—it just allows you to introduce additional refinements that depend on purely mechanical factors. Similarly, the introduction of word-processing software didn’t appreciably reduce how long it takes to write a novel: it only restructures it, so that whatever time you save in typing is expended in making imperceptible corrections. This isn’t always a good thing. As the history of animation makes clear, Blinn’s Law can lead to the same tired stories being played out against photorealistic backgrounds, and access to word processors may simply mean that the average story gets longer, as Ted Hughes observed while serving on the judging panel of a children’s writing competition: “It just extends everything slightly too much. Every sentence is too long. Everything is taken a bit too far, too attenuated.” But there are also cases in which an artist’s natural patience and tolerance for work provides the finished result with the rendering time that it needs to reach its ideal form. And we have it to thank for many displays of gratuitous craft and beauty.

This leads me to a conclusion that I’ve recently come to appreciate more fully, which is that every form of artistic activity is equally difficult. I don’t mean that the violin is as easy as the ukulele, or that there isn’t any difference between performance at a high level and the efforts of a casual hobbyist. But if you’re a creative professional and take your work seriously, you’re usually going to operate at your optimum capacity, if not all the time, than at least on average. Each day’s work is determined less by the demands of the project itself than by how much energy you can afford to give it. I switch fairly regularly between fiction and nonfiction, for instance, and whenever I’m working in one mode, I often find myself thinking fondly of the other, which somehow seems easier in my imagination. But it isn’t. I’m the same person with an identical set of habits whether I’m writing a novel, a short story, or an essay, and an hour of my time is pitched about at the same degree of intensity no matter what the objective is. In practice, it settles at a point that is slightly too intense to be entirely comfortable, but not so much that it burns me out. I’ve found that I unconsciously adjust the conditions to make each day’s work feel the same, either by moving a deadline forward or backward or by taking on projects that are progressively more challenging. (This doesn’t just apply to paid work, either. The amount of time I spend on this blog hasn’t varied much over the last five years, but the posts have definitely gotten more involved.) This also applies to particular stages. When I’m researching, outlining, writing, or revising, I sometimes console myself with the idea that the next part will be easier. In fact, it’s all hard. And if it isn’t, I’m doing something wrong.

This implies that we shouldn’t pick our artistic pursuits based on how easy they are, but on the quality that they yield for each unit of time invested. (“Quality” can mean whatever you like, from how much you get paid to the amount of personal satisfaction that you derive.) I work as diligently as possible on whatever I do, but this doesn’t mean that I’m equally good at everything, and there are certain forms of writing that I’ve given up because they don’t justify the cost. And I’ve also learned to be grateful for the fact that everything I do takes about the same amount of time and effort per page. The real limiting factor isn’t the time available, but what I bring to each creative hour, and over the long run, it makes sense to be as consistent as I can. It isn’t intensity that hurts, but volatility, and you lose a lot in ramping up and ramping down. But the appropriate level varies from one person to another. What Parkinson neglects to mention in his contrast between “an elderly lady of leisure” and “a busy man” is that each of them has presumably found a suitable mode of living, and you can find productive writers and artists who fall into either category. In the end, the process is all we have, and it makes sense that it would remain the same in its externals, regardless of its underlying goal. That’s a gentler way of stating Parkinson’s Law, but it’s no less accurate. And Parkinson himself seems to have softened his stance. As he said in an interview to the New York Times toward the end of his career: “My experience tells me the only thing people really enjoy over a long period of time is some kind of work.”

Quote of the Day

Verse comedy is interesting to me because of the challenge of writing in rhymed couplets, which is not a form that’s usually amenable to English, yet to me it gives great possibility for comedy. When I did my first verse comedy, I realized that there was this incredible musical/comedic instrument available to me. Working in verse is a way to compress language but also explode language and make it more expressive. Prose, after all—especially realistic prose—is a pretty depressing instrument, really. It’s like playing on a harmonica instead of a piano. I think everything should be in verse. The New York Times should be in verse.

—David Ives, to The Economist