Posts Tagged ‘John W. Campbell’

“At the Fall” and Beyond

The May/June issue of Analog Science Fiction and Fact includes my new novelette “At the Fall,” a big excerpt of which you can read now on the magazine’s official site. It’s one of my favorite stories that I’ve ever written, and I’m especially pleased by the interior illustration by Eldar Zakirov, pictured above, which you can see in greater detail here. I don’t think I’ll have the chance to write up the kind of extended account of this story’s conception that I’ve provided for other works in the past, but if you’re curious about its origins, Analog has posted a fun conversation on its blog in which I talk about it with Frank Wu, the author of “In the Absence of Instructions to the Contrary,” which appeared in the magazine a few years ago. (Our stories have a number of interesting parallels that only came to light after I wrote and submitted mine, and I think that the result is a nice case study of what happens when two writers end up independently pursuing a similar idea.) There’s also a thoughtful editorial by former Analog editor Stanley Schmidt about his relationship with John W. Campbell, inspired by a panel that we held at last year’s World Science Fiction Convention. Enjoy!

Visions of tomorrow

As I’ve mentioned here before, one of my few real regrets about Astounding is that I wasn’t able to devote much room to discussing the artists who played such an important role in the evolution of science fiction. (The more I think about it, the more it seems to me that their collective impact might be even greater than that of any of the writers I discuss, at least when it comes to how the genre influenced and was received by mainstream culture.) Over the last few months, I’ve done my best to address this omission, with a series of posts on such subjects as Campbell’s efforts to improve the artwork, his deliberate destruction of the covers of Unknown, and his surprising affection for the homoerotic paintings of Alejandro Cañedo. And I can reveal now that this was all in preparation for a more ambitious project that has been in the works for a while—a visual essay on the art of Astounding and Unknown that has finally appeared online in the New York Times Book Review, with the highlights scheduled to be published in the print edition this weekend. It took a lot of time and effort to put it together, especially by my editors, and I’m very proud of the result, which honors the visions of such artists as H.W. Wesso, Howard V. Brown, Hubert Rogers, Manuel Rey Isip, Frank Kelly Freas, and many others. It stands on its own, but I’ve come to think of it as an unpublished chapter from my book that deserves to be read alongside its longer companion. As I note in the article, it took years for the stories inside the magazine to catch up to the dreams of its readers, but the artwork was often remarkable from the beginning. And if you want to know what the fans of the golden age really saw when they imagined the future, the answer is right here.

The fairy tale theater

It must have all started with The Princess Switch, although that’s so long ago now that I can barely remember. Netflix was pushing me hard to watch an original movie with Vanessa Hudgens in a dual role as a European royal and a baker from Chicago who trade places and end up romantically entangled with each other’s love interests at Christmas, and I finally gave in. In the weeks since, my wife and I have watched Pride, Prejudice, and Mistletoe; The Nine Lives of Christmas; Crown for Christmas; The Holiday Calendar; Christmas at the Palace; and possibly one or two others that I’ve forgotten. A few were on Netflix, but most were on Hallmark, which has staked out this space so aggressively that it can seem frighteningly singleminded in its pursuit of Yuletide cheer. By now, it airs close to forty original holiday romances between Thanksgiving and New Year’s Eve, and like its paperback predecessors, it knows better than to tinker with a proven formula. As two of its writers anonymously reveal in an interview with Entertainment Weekly:

We have an idea and it maybe takes us a week or so just to break it down into a treatment, a synopsis of the story; it’s like a beat sheet where you pretty much write what’s going to happen in every scene you just don’t write the scene. If we have a solid beat sheet done and it’s approved, then it’s only going to take us about a week and a half to finish a draft. Basically, an act or two a day and there’s nine. They’re kind of simple because there are so many rules so you know what you can and can’t do, and if you have everything worked out it comes together.

And the rules are revealing in themselves. As one writer notes: “The first rule is snow. We really wanted to do one where the basic conflict was a fear that there will not be snow on Christmas. We were told you cannot do that, there must be snow. They can’t be waiting for the snow, there has to be snow. You cannot threaten them with no snow.” And the conventions that make these movies so watchable are built directly into the structure:

There cannot be a single scene that does not acknowledge the theme. Well, maybe a scene, but you can’t have a single act that doesn’t acknowledge it and there are nine of them, so there’s lots of opportunities for Christmas. They have a really rigid nine-act structure that makes writing them a lot of fun because it’s almost like an exercise. You know where you have to get to: People have to be kissing for the first time, probably in some sort of a Christmas setting, probably with snow falling from the sky, probably with a small crowd watching. You have to start with two people who, for whatever reason, don’t like each other and you’re just maneuvering through those nine acts to get them to that kiss in the snow.

The result, as I’ve learned firsthand, is a movie that seems familiar before you’ve even seen it. You can watch with one eye as you’re wrapping presents, or tune in halfway through with no fear of becoming confused. It allows its viewers to give it exactly as much attention as they’re willing to spare, and at a time when the mere act of watching prestige television can be physically exhausting, there’s something to be said for an option that asks nothing of us at all.

After you’ve seen two or three of these movies, of course, the details start to blur, particularly when it comes to the male leads. The writers speak hopefully of making the characters “as unique and interesting as they can be within the confines of Hallmark land,” but while the women are allowed an occasional flash of individuality, the men are unfailingly generic. This is particularly true of the subgenre in which the love interest is a king or prince, who doesn’t get any more personality than his counterpart in fairy tales. Yet this may not be a flaw. In On Directing Film, which is the best work on storytelling that I’ve ever read, David Mamet provides a relevant word of advice:

In The Uses of Enchantment, Bruno Bettelheim says of fairy tales the same thing Alfred Hitchcock said about thrillers: that the less the hero of the play is inflected, identified, and characterized, the more we will endow him with our own internal meaning—the more we will identify with him—which is to say the more we will be assured that we are that hero. “The hero rode up on a white horse.” You don’t say “a short hero rode up on a white horse,” because if the listener isn’t short he isn’t going to identify with that hero. You don’t say “a tall hero rode up on a white horse,” because if the listener isn’t tall, he won’t identify with the hero. You say “a hero,” and the audience subconsciously realize they are that hero.

Yet Mamet also overlooks the fact that the women in fairy tales, like Snow White, are often described with great specificity—it’s the prince who is glimpsed only faintly. Hallmark follows much the same rule, which implies that it’s less important for the audience to identify with the protagonist than to fantasize without constraint about the object of desire.

This also leads to some unfortunate decisions about diversity, which is more or less what you might expect. As one writer says candidly to Entertainment Weekly:

On our end, we just write everybody as white, we don’t even bother to fight that war. If they want to put someone of color in there, that would be wonderful, but we don’t have control of that…I found out Meghan Markle had been in some and she’s biracial, but it almost seems like they’ve tightened those restrictions more recently. Everything’s just such a white, white, white, white world. It’s a white Christmas after all—with the snow and the people.

With more than thirty original movies coming out every year, you might think that Hallmark could make a few exceptions, especially since the demand clearly exists, but this isn’t about marketing at all. It’s a reflection of the fact that nonwhiteness is still seen as a token of difference, or a deviation from an assumed norm, and it’s the logical extension of the rules that I’ve listed above. White characters have the privilege—which is invisible but very real—of seeming culturally uninflected, which is the baseline that allows the formula to unfold. This seems very close to John W. Campbell’s implicit notion that all characters in science fiction should be white males by default, and while other genres have gradually moved past this point, it’s still very much the case with Hallmark. (There can be nonwhite characters, but they have to follow the rules: “Normally there’ll be a black character that’s like a friend or a boss, usually someone benevolent because you don’t want your one person of color to not be positive.”) With diversity, as with everything else, Hallmark is very mindful of how much variation its audience will accept. It thinks that it knows the formula. And it might not even be wrong.

The soul of a new machine

Over the weekend, I took part in a panel at Windycon titled “Evil Computers: Why Didn’t We Just Pull the Plug?” Naturally, my mind turned to the most famous evil computer in all of fiction, so I’ve been thinking a lot about HAL, which made me all the more sorry to learn yesterday of the death of voice actor Douglas Rain. (Stan Lee also passed away, of course, which is a subject for a later post.) I knew that Rain had been hired to record the part after Stanley Kubrick was dissatisfied by an earlier attempt by Martin Balsam, but I wasn’t aware that the director had a particular model in mind for the elusive quality that he was trying to evoke, as Kate McQuiston reveals in the book We’ll Meet Again:

Would-be HALs included Alistair Cooke and Martin Balsam, who read for the part but was deemed too emotional. Kubrick set assistant Benn Reyes to the task of finding the right actor, and expressly not a narrator, to supply the voice. He wrote, “I would describe the quality as being sincere, intelligent, disarming, the intelligent friend next door, the Winston Hibler/Walt Disney approach. The voice is neither patronizing, nor is it intimidating, nor is it pompous, overly dramatic, or actorish. Despite this, it is interesting. Enough said, see what you can do.” Even Kubrick’s U.S. lawyer, Louis Blau, was among those making suggestions, which included Richard Basehart, José Ferrer, Van Heflin, Walter Pigeon, and Jason Robards. In Douglas Rain, who had experience both as an actor and a narrator, Kubrick found just what he was looking for: “I have found a narrator…I think he’s perfect, he’s got just the right amount of the Winston Hibler, the intelligent friend next door quality, with a great deal of sincerity, and yet, I think, an arresting quality.”

Who was Winston Hibler? He was the producer and narrator for Disney who provided voiceovers for such short nature documentaries as Seal Island, In Beaver Valley, and White Wilderness, and the fact that Kubrick used him as a touchstone is enormously revealing. On one level, the initial characterization of HAL as a reassuring, friendly voice of information has obvious dramatic value, particularly as the situation deteriorates. (It’s the same tactic that led Richard Kiley to figure in both the novel and movie versions of Jurassic Park. And I have to wonder whether Kubrick ever weighed the possibility of hiring Hibler himself, since in other ways, he clearly spared no expense.) But something more sinister is also at play. As I’ve mentioned before, Disney and its aesthetic feels weirdly central to the problem of modernity, with its collision between the sentimental and the calculated, and the way in which its manufactured feeling can lead to real memories and emotion. Kubrick, a famously meticulous director who looked everywhere for insights into craft, seems to have understood this. And I can’t resist pointing out that Hibler did the voiceover for White Wilderness, which was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Documentary Short, but also included a scene in which the filmmakers deliberately herded lemmings off a cliff into the water in a staged mass suicide. As Hibler smoothly narrates in the original version: “A kind of compulsion seizes each tiny rodent and, carried along by an unreasoning hysteria, each falls into step for a march that will take them to a strange destiny. That destiny is to jump into the ocean. They’ve become victims of an obsession—a one-track thought: ‘Move on! Move on!’ This is the last chance to turn back, yet over they go, casting themselves out bodily into space.”

And I think that Kubrick’s fixation on Hibler’s voice, along with the version later embodied by Rain, gets at something important about our feelings toward computers and their role in our lives. In 2001, the astronauts are placed in an artificial environment in which their survival depends on the outwardly benevolent HAL, and one of the central themes of science fiction is what happens when this situation expands to encompass an entire civilization. It’s there at the very beginning of the genre’s modern era, in John W. Campbell’s “Twilight,” which depicts a world seven million years in the future in which “perfect machines” provide for our every need, robbing the human race of all initiative. (Campbell would explore this idea further in “The Machine,” and he even offered an early version of the singularity—in which robots learn to build better versions of themselves—in “The Last Evolution.”) Years later, Campbell and Asimov put that relationship at the heart of the Three Laws of Robotics, the first of which states: “A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.” This sounds straightforward enough, but as writers realized almost right away, it hinges on the definition of certain terms, including “human being” and “harm,” that are slipperier than they might seem. Its ultimate expression was Jack Williamson’s story “With Folded Hands,” which carried the First Law to its terrifying conclusion. His superior robots believe that their Prime Directive is to prevent all forms of unhappiness, which prompts them to drug or lobotomize any human beings who seem less than content. As Williamson said much later in an interview with Larry McCaffery: “The notion I was consciously working on specifically came out of a fragment of a story I had worked on for a while about an astronaut in space who is accompanied by a robot obviously superior to him physically…Just looking at the fragment gave me the sense of how inferior humanity is in many ways to mechanical creations.”

Which brings us back to the singularity. Its central assumption was vividly expressed by the mathematician I.J. Good, who also served as a consultant on 2001:

Let an ultraintelligent machine be defined as a machine that can far surpass all the intellectual activities of any man however clever. Since the design of machines is one of these intellectual activities, an ultraintelligent machine could design even better machines; there would then unquestionably be an ‘intelligence explosion,’ and the intelligence of man would be left far behind. Thus the first ultraintelligent machine is the last invention that man need ever make, provided that the machine is docile enough to tell us how to keep it under control.

That last clause is a killer, but even if we accept that such a machine would be “docile,” it also embodies the fear, which Campbell was already exploring in the early thirties, of a benevolent dictatorship of machines. And the very Campbellian notion of “the last invention” should be frightening in itself. The prospect of immortality may be enticing, but not if it emerges through a technological singularity that leaves us unprepared to deal with the social consequences, rather than through incremental scientific and medical progress—and the public debate that it ought to inspire—that human beings have earned for themselves. I can’t imagine anything more nightmarish than a world in which we can all live forever without having gone through the necessary ethical, political, and ecological stages to make such a situation sustainable. (When I contemplate living through the equivalent of the last two years over the course of millennia, the notion of eternal life becomes considerably less attractive.) Our fear of computers taking over our lives, whether on a spacecraft or in society as a whole, is really about the surrender of control, even in the benevolent form embodied by Disney. And when I think of the singularity now, I seem to hear it speaking with Winston Hibler’s voice: “Move on! Move on!”

The ethereal phase

Like many readers, I first encountered the concept of the singularity—the idea that artificial intelligence will eventually lead to an era of exponential technological change—through the work of the futurist Ray Kurzweil. Fifteen years ago, I was browsing in a bookstore when I came across a copy of his book The Singularity is Near, which I bought on the spot. Kurzweil’s thesis is a powerful one, and, to a point, it remains completely convincing:

What, then, is the Singularity? It’s a future period during which the pace of technological change will be so rapid, its impact so deep, that human life will be irreversibly transformed…The key idea underlying the impending Singularity is that the pace of change of our human-created technology is accelerating and its powers are expanding at an exponential pace. Exponential growth is deceptive. It starts out almost imperceptibly and then explodes with unexpected fury—unexpected, that is, if one does not take care to follow its trajectory.

Kurzweil seems particularly enthusiastic about one purported consequence of this development: “We will gain power over our fates. Our mortality will be in our own hands. We will be able to live as long as we want (a subtly different statement from saying we will live forever).” And he suggests that the turning point will occur “before the middle of this century.”

This line of thinking, which was much more novel back then than it is today, was enough to briefly turn me into a transhumanist, or at least into the approximation of one. But I’m more skeptical now. As I noted here recently, one of Kurzweil’s core arguments—that incremental advances in medical technology will lead to functional immortality to those who can hang around for long enough—was advanced by John W. Campbell as far back as 1949. (Writing in Astounding Science Fiction, Campbell muses that a child will be born one day who never has to do die, and he concludes: “I wonder if that point has been passed? And my own guess is—it has.” There’s no proof yet that he was wrong, but I have my doubts.) And the notion of accelerating change is even older. The historian Henry Adams explores the possibility in an essay published in 1904, and a few years later, in the book Degradation of the Democratic Dogma, he writes of the pace of technological progress:

As each newly appropriated force increased the attraction between the sum of nature’s forces and the volume of human mind, by the usual law of squares, the acceleration hurried society towards the critical point that marked the passage into a new phase as though it were heat impelling water to explode as steam…The curve resembles that of the vaporization of water. The resemblance is too close to be disregarded, for nature loves the logarithm, and perpetually recurs to her inverse square. For convenience, if only as a momentary refuge, the physicist-historian will probably have to try the experiment of taking the law of inverse squares as his standard of social acceleration for the nineteenth century, and consequently for the whole phase, which obliges him to accept it experimentally as a general law of history.

Adams thought that the point of no return would occur around 1917, while Buckminster Fuller, writing over a generation later, speculated that technological change would lead to a post-scarcity society sometime in the late seventies. Such futurists tend to place the pivotal moment at a far enough remove to be plausible, while still potentially within their own lifetimes, which hints at the element of wishful thinking involved. (It’s worth noting that the same amount of time has passed since the publication of The Singularity is Near as elapsed between Adams’s first essay on the subject and the date that he posited for what he liked to call the Ethereal Phase.) And unlike other prophets, they benefit from their ability to frame such speculations in the language of science—and especially of physics and mathematics. Writing from the point of view of a historian, in fact, Adams arrives at something that sounds remarkably like psychohistory:

If values can be given to these attractions, a physical theory of history is a mere matter of physical formula, no more complicated than the formulas of Willard Gibbs or Clerk Maxwell; but the task of framing the formula and assigning the values belongs to the physicist, not to the historian…If the physicist-historian is satisfied with neither of the known laws of mass, astronomical or electric, and cannot arrange his variables in any combination that will conform with a phase-sequence, no resource seems to remain but that of waiting until his physical problems shall be solved, and he shall be able to explain what Force is…Probably the solution of any one of the problems will give the solution for them all.

And each of these men sees exactly what he wants to find in this phenomenon, which amounts to a kind of Rorschach test for futurists. On my bookshelf, I have a book titled The 10% Solution to a Healthy Life, which outlines a health plan based largely on the work of Nathan Pritikin, whose thoughts on diet—and longevity—have turned out to be surprisingly influential. Its author says of his decision to write a book: “Being a scientist and a trained skeptic, I was always turned off by people with strong singular agendas. People out to save my soul or even just my health or well-being were strongly suspect. I felt very uncomfortable, therefore, in this role myself, telling people how they should eat or live.” The author was Ray Kurzweil. He makes no mention of the singularity here, but after another decade, he had moved on to such titles as Fantastic Voyage: Live Long Enough to Live Forever and Transcend: Nine Steps to Living Well Forever. Immortality clearly matters a lot to him, which naturally affects how he views the prospect of accelerating change. By contrast, Adams was most attracted by the possibility of refining the theory of history into a science, as Campbell and Asimov later were, while Fuller saw it as the means to an ecological utopia, which had less to do with environmental awareness than with his desire to free the world’s population to do whatever it wanted with its time. Kurzweil, in turn, sees it as a way for us to live for as long as we want, which is an interest that predated his public association with the singularity, and this is reason enough to be skeptical of everything that he says. Kurzweil is a genius, but he’s also just about the last person we should trust to be objective when it comes to the consequences of accelerating change. I’ll be talking about this more tomorrow.

The Men Who Saw Tomorrow, Part 3

By now, it might seem obvious that the best way to approach Nostradamus is to see it as a kind of game, as Anthony Boucher describes it in the June 1942 issue of Unknown Worlds: “A fascinating game, to be sure, with a one-in-a-million chance of hitting an astounding bullseye. But still a game, and a game that has to be played according to the rules. And those rules are, above all things else, even above historical knowledge and ingenuity of interpretation, accuracy and impartiality.” Boucher’s work inspired several spirited rebukes in print from L. Sprague de Camp, who granted the rules of the game but disagreed about its harmlessness. In a book review signed “J. Wellington Wells”—and please do keep an eye on that last name—de Camp noted that Nostradamus was “conjured out of his grave” whenever there was a war:

And wonder of wonders, it always transpires that a considerable portion of his several fat volumes of prophetic quatrains refer to the particular war—out of the twenty-odd major conflicts that have occurred since Dr. Nostradamus’s time—or other disturbance now taking place; and moreover that they prophesy inevitable victory for our side—whichever that happens to be. A wonderful man, Nostradamus.

Their affectionate battle culminated in a nonsense limerick that de Camp published in the December 1942 version of Esquire, claiming that if it was still in print after four hundred years, it would have been proven just as true as any of Nostradamus’s prophecies. Boucher responded in Astounding with the short story “Pelagic Spark,” an early piece of fanfic in which de Camp’s great-grandson uses the “prophecy” to inspire a rebellion in the far future against the sinister Hitler XVI.

This is all just good fun, but not everyone sees it as a game, and Nostradamus—like other forms of vaguely apocalyptic prophecy—tends to return at exactly the point when such impulses become the most dangerous. This was the core of de Camp’s objection, and Boucher himself issued a similar warning:

At this point there enters a sinister economic factor. Books will be published only when there is popular demand for them. The ideal attempt to interpret the as yet unfulfilled quatrains of Nostradamus would be made in an ivory tower when all the world was at peace. But books on Nostradamus sell only in times of terrible crisis, when the public wants no quiet and reasoned analysis, but an impassioned assurance that We are going to lick the blazes out of Them because look, it says so right here. And in times of terrible crisis, rules are apt to get lost.

Boucher observes that one of the best books on the subject, Charles A. Ward’s Oracles of Nostradamus, was reissued with a dust jacket emblazoned with such questions as “Will America Enter the War?” and “Will the British Fleet Be Destroyed?” You still see this sort of thing today, and it isn’t just the books that benefit. In 1981, the producer David L. Wolper released a documentary on the prophecies of Nostradamus, The Man Who Saw Tomorrow, that saw subsequent spikes in interest during the Gulf War—a revised version for television was hosted by Charlton Heston—and after the September 11 attacks, when there was a run on the cassette at Blockbuster. And the attention that it periodically inspires reflects the same emotional factors that led to psychohistory, as the host of the original version said to the audience: “Do we really want to know about the future? Maybe so—if we can change it.”

The speaker, of course, was Orson Welles. I had always known that The Man Who Saw Tomorrow was narrated by Welles, but it wasn’t until I watched it recently that I realized that he hosted it onscreen as well, in one of my favorite incarnations of any human being—bearded, gigantic, cigar in hand, vaguely contemptuous of his surroundings and collaborators, but still willing to infuse the proceedings with something of the velvet and gold braid. Keith Phipps of The A.V. Club once described the documentary as “a brain-damaged sequel” to Welles’s lovely F for Fake, which is very generous. The entire project is manifestly ridiculous and exploitative, with uncut footage from the Zapruder film mingling with a xenophobic fantasy of a war of the West against Islam. Yet there are also moments that are oddly transporting, as when Welles turns to the camera and says:

Before continuing, let me warn you now that the predictions of the future are not at all comforting. I might also add that these predictions of the past, these warnings of the future are not the opinions of the producers of the film. They’re certainly not my opinions. They’re interpretations of the quatrains as made by scores of independent scholars of Nostradamus’ work.

In the sly reading of “my opinions,” you can still hear a trace of Harry Lime, or even of Gregory Arkadin, who invited his guests to drink to the story of the scorpion and the frog. And the entire movie is full of strange echoes of Welles’s career. Footage is repurposed from Waterloo, in which he played Louis XVIII, and it glances at the fall of the Shah of Iran, whose brother-in-law funded Welles’s The Other Side of the Wind, which was impounded by the revolutionary government that Nostradamus allegedly foresaw.

Welles later expressed contempt for the whole affair, allegedly telling Merv Griffin that you could get equally useful prophecies by reading at random out of the phone book. Yet it’s worth remembering, as the critic David Thomson notes, that Welles turned all of his talk show interlocutors into versions of the reporter from Citizen Kane, or even into the Hal to his Falstaff, and it’s never clear where the game ended. His presence infuses The Man Who Saw Tomorrow with an unearned loveliness, despite the its many awful aspects, such as the presence of the “psychic” Jeane Dixon. (Dixon’s fame rested on her alleged prediction of the Kennedy assassination, based on a statement—made in Parade magazine in 1960—that the winner of the upcoming presidential election would be “assassinated or die in office though not necessarily in his first term.” Oddly enough, no one seems to remember an equally impressive prediction by the astrologer Joseph F. Goodavage, who wrote in Analog in September 1962: “It is coincidental that each American president in office at the time of these conjunctions [of Jupiter and Saturn in an earth sign] either died or was assassinated before leaving the presidency…John F. Kennedy was elected in 1960 at the time of a Jupiter and Saturn conjunction in Capricorn.”) And it’s hard for me to watch this movie without falling into reveries about Welles, who was like John W. Campbell in so many other ways. Welles may have been the most intriguing cultural figure of the twentieth century, but he never seemed to know what would come next, and his later career was one long improvisation. It might not be too much to hear a certain wistfulness when he speaks of the man who could see tomorrow, much as Campbell’s fascination with psychohistory stood in stark contrast to the confusion of the second half of his life. When The Man Who Saw Tomorrow was released, Welles had finished editing about forty minutes of his unfinished masterpiece The Other Side of the Wind, and for decades after his death, it seemed that it would never be seen. Instead, it’s available today on Netflix. And I don’t think that anybody could have seen that coming.

The Men Who Saw Tomorrow, Part 1

If there’s a single theme that runs throughout my book Astounding, it’s the two sides of the editor John W. Campbell. These days, Campbell tends to be associated with highly technical “hard” science fiction with an emphasis on physics and engineering, but he had an equally dominant mystical side, and from the beginning, you often see the same basic impulses deployed in both directions. (After the memory of his career had faded, much of this history was quietly revised, as Algis Burdrys notes in Benchmarks Revisited: “The strong mystical bent displayed among even the coarsest cigar-chewing technists is conveniently overlooked, and Campbell’s subsequent preoccupation with psionics is seen as an inexplicable deviation from a life of hitherto unswerving straight devotion to what we all agree is reasonability.”) As an undergraduate at M.I.T. and Duke, Campbell was drawn successively to Norbert Wiener, the founder of cybernetics, and Joseph Rhine, the psychologist best known for his statistical studies of telepathy. Both professors fed into his fascination with a possible science of the mind, but along strikingly different lines, and he later pursued both dianetics, which he originally saw as a kind of practical cybernetics, and explorations of psychic powers. Much the same holds true of his other great obsession—the problem of foreseeing the future. As I discuss today in an essay in the New York Times, its most famous manifestation was the notion of psychohistory, the fictional science of prediction in Asimov’s Foundation series. But at a time of global uncertainty, it wasn’t the method of forecasting that counted, but the accuracy of the results, and even as Campbell was collaborating with Asimov, his interest in prophecy was taking him to even stranger places.

The vehicle for the editor’s more mystical explorations was Unknown, the landmark fantasy pulp that briefly channeled these inclinations away from the pages of Astounding. (In my book, I argue that the simultaneous existence of these two titles purified science fiction at a crucial moment, and that the entire genre might have evolved in altogether different ways if Campbell had been forced to express all sides of his personality in a single magazine.) As I noted here the other day, in an attempt to attract a wider audience, Campbell removed the cover paintings from Unknown, hoping to make it look like a more mainstream publication. The first issue with the revised design was dated July 1940, and in his editor’s note, Campbell explicitly addressed the “new discoverers” who were reading the magazine for the first time. He grandly asserted that fantasy represented “a completely untrammeled literary medium,” and as an illustration of the kinds of subjects that he intended to explore in his stories, he offered a revealing example:

Until somebody satisfactorily explains away the unquestionable masses of evidence showing that people do have visions of things yet to come, or of things occurring at far-distant points—until someone explains how Nostradamus, the prophet, predicted things centuries before they happened with such minute detail (as to names of people not to be born for half a dozen generations or so!) that no vague “Oh, vague generalities—things are always happening that can be twisted to fit!” can possibly explain them away—until the time those are docketed and labeled and nearly filed—they belong to The Unknown.

It was Campbell’s first mention in print of Nostradamus, the sixteenth-century French prophet, but it wouldn’t be the last. A few months later, Campbell alluded in another editorial to the Moberly-Jourdain incident, in which two women claimed to have traveled over a century back in time on a visit to the Palace of Versailles. The editor continued: “If it happens one way—how about the other? How about someone slipping from the past to the future? It is known—and don’t condemn till you’ve read a fair analysis of the old man’s works—that Nostradamus, the famous French prophet, did not guess at what might happen; he recorded what did happen—before it happened. His accuracy of prophecy runs considerably better, actually, than the United States government crop forecasts, in percentage, and the latter are certainly used as a basis for business.” Campbell then drew a revealing connection between Nostradamus and the war in Europe:

Incidentally, to avoid disappointment, Nostradamus did not go into much detail about this period. He was writing several hundred years ago, for people of that time—and principally for Parisians. He predicted in some detail the French Revolution, predicted several destructions of Paris—which have come off on schedule, to date—and did not predict destruction of Paris for 1940. He did, however, for 1999—by a “rain of fire from the East.” Presumably he didn’t have any adequate terms for airplane bombs, so that may mean thermite incendiaries. But the present period, too many centuries from his own times, would be of minor interest to him, and details are sketchy. The prophecy goes up to about the thirty-fifth century.

And the timing was highly significant. Earlier that year, Campbell had published the nonfiction piece “The Science of Whithering” by L. Sprague de Camp in Astounding, shortly after German troops marched into Paris. De Camp’s article, which discussed the work of such cyclical historians as Spengler and Toynbee, represented the academic or scientific approach the problem of forecasting, and it would soon find its fictional expression in such stories as Jack Williamson’s “Breakdown” and Asimov’s “Foundation.” As usual, however, Campbell was playing both sides, and he was about to pursue a parallel train of thought in Unknown that has largely been forgotten. Instead of attempting to explain Nostradamus in rational terms, Campbell ventured a theory that was even more fantastic than the idea of clairvoyance:

Occasionally a man—vanishes…And somehow, he falls into another time. Sometimes future—sometimes past. And sometimes he comes back, sometimes he doesn’t. If he does come back, there’d be a tendency, and a smart one, to shut up; it’s mighty hard to prove. Of course, if he’s a scholarly gentlemen, he might spend his unintentional sojourn in the future reading histories of his beloved native land. Then, of course, he ought to be pretty accurate at predicting revolutions and destruction of cities. Even be able to name inconsequential details, as Nostradamus did.

To some extent, this might have been just a game that he was playing for his readers—but not completely. Campbell’s interest in Nostradamus was very real, and just as he had used Williamson and Asimov to explore psychohistory, he deployed another immensely talented surrogate to look into the problem of prophecy. His name was Anthony Boucher. I’ll be exploring this in greater detail tomorrow.

Note: Please join me today at 12:00pm ET for a Twitter AMA to celebrate the release of the fantastic new horror anthology Terror at the Crossroads, which includes my short story “Cryptids.”

The beauty of the world

In the fall of 1953, the science fiction editor John W. Campbell visited the Museum of Modern Art in New York. He wasn’t impressed, saying that the results could have been “duplicated in any major insane asylum” and that modern art was the expression of a “violent neurosis.” But the trip wasn’t entirely wasted. As he wrote in a letter to his father, Campbell and his wife Peg were able to spend the day in the company of a good friend:

We went with Alejandro Cañedo, a fine-arts partner friend of mine. We’d just been up to his apartment to see his incredibly lovely land-sea-sky-scapes. He does beach scenes that look as though they might have been painted 3,000,000,000 years ago in the pre-Cambrian period, where raw rock meets long, curling waves, under a vast, spacious sky. He can actually paint a cloud so it looks like a cloud, instead of a bit of white cotton fluff. The pictures are magnificently spacious, and patient and calm. They have eternity and timelessness and action built in them all at once.

Campbell continued: “I was very glad [Cañedo] was along when we went to the museum. He is an artist, and an artist who can, and does, paint beauty. He’s a gentleman, a philosopher, and he’s lived in a number of parts of the world. Mexican by birth, served in the Mexican state department, and studied in Paris and Rome.” And Campbell drew a strong contrast between Cañedo’s “incredibly lovely” canvases and the excesses of abstract act, which was full of nothing but “hate and anger and confusion and frustration.”

And the artist whom Campbell described in another letter as “considerable of a philosopher” was a fascinating figure in his own right. He was born Alejandro de Cañedo in Mexico City in 1902, which made him nearly a decade older than Campbell, and he became known for his exquisitely rendered male figure studies, which he later exhibited under the name Alexander Cañedo. For the December 1946 issue of Astounding, he provided a cover painting for Eric Frank Russell’s “Metamorphosite,” but he might never have made any impression on the magazine’s fans—or its editor—if it hadn’t been for a happy accident. As Campbell told readers the following August:

Item the first is Astounding’s cover for September. It’s different. It’s unique. And it’s more than good. It came about in the following way; Alejandro Cañedo, who did our last cover, was in, and invited me to come up to his studio where he had some paintings he was about to ship to a showing. I did. And he had some strikingly beautiful and wholly unique artwork. I had never seen anything like it—and immediately demanded why he hadn’t done one like that for Astounding.

Campbell concluded: “It seems that Cañedo doing what he likes, and Cañedo doing what he thinks someone else wants, are quite, quite different. I think you’ll want a lot more of the type he’s done. And I can’t describe it.” The cover of the September issue featured the painting reproduced above, and over the next few years, Campbell published several more “symbolic” covers credited to “Alejandro,” which were striking images that didn’t illustrate any specific story.

As even a casual glance reveals, they were also blatantly homoerotic. I haven’t been able to find much in the way of biographical information on Cañedo, but his work appears in the permanent collection of the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art, and his article on Wikipedia includes the unsourced statement that he painted works of gay erotica for private collectors that couldn’t be displayed in public. And it’s very hard to look at these covers now and see them as anything but erotic reveries. (Even at the time, Cañedo’s cover for the July 1954 issue, titled “Inappropriate,” apparently made some fans uncomfortable, although few seem to have seen anything strange about this cover from several years earlier.) Campbell doesn’t appear to have noticed anything out of the ordinary, and his unabashed admiration for Cañedo’s work stands in remarkable contrast to the sentiments that he expressed elsewhere. Just one year after Cañedo’s first “symbolic” cover, he published an article in which Dr. Joseph Winter, who later became a member of the original dianetics team, expressed the hope that endocrinology would lead to a world with “no homosexuality.” Campbell later claimed that dianetics had been used for successful “cures” of gay men, and he stated both in private and in the pages of the magazine that homosexuality was a sign of cultural decline. And he didn’t think that he had any trouble identifying such individuals, writing in an unbelievably horrifying passage in a letter to Isaac Asimov in 1958:

And Ike, my friend, consider the case of a fairy, a queer. They can, normally, be spotted about as far off as you can spot a mulatto. I’ll admit a coal-black Negro can be spotted a bit further than a fairy can, but the normal mulatto can’t. Sure, I know a lot of queers don’t look that way—but they’re simply “passing.”

But I’m frankly more interested in what in the world Cañedo thought of Campbell. Even in the rare glimpses that we find in Campbell’s letters, it’s possible to discern glints of an ironic humor. (In a another letter to his father, the editor quoted Cañedo’s philosophy of life: “Sometimes I have not had a nickel in the bank, and sometimes I’ve had plenty, but I have been rich all the time, because I have had the friends I want to talk to, the work I want to do, and the things I want to learn about.” The same letter includes another anecdote that makes me wonder: “By the way, Alex had his apartment redecorated, and had a painter repaint the walls. Alex was out while the painter was on the job; when Alex came back that evening he made a horrifying discovery. God knows how that could be, but the painter was red-green colorblind! Instead of painting the walls the pale tan Alex wanted, he’d done them in a sort of baby pink!” God knows how indeed.) And it’s worth juxtaposing Campbell’s unqualified admiration for Cañedo’s nudes, which he saw as an answer to the lunacy of modern art, with his editorial of December 1958:

In England, there is a strong movement to remove homosexuality from the list of crimes. After all, we mustn’t impose our opinions on others, must we? Yes…and homosexuality was accepted in Greece, just before its fall. And in Rome, in the latter days. And in Hitlerite Germany. After all, now, you can’t prove, logically, that the homosexual doesn’t have as much right to his opinion as you do to yours, can you?

But perhaps we should just be glad that Campbell was obtuse enough to publish these remarkable covers. As he wrote to his father of modern artists: “They don’t want to see the truth, and reject seeing the beauty of the world. That an individual can make such a mistake is perfectly understandable.”

The unknown future

During the writing of Astounding, I often found myself wondering how much control an editor can really have. John W. Campbell is routinely described as the most powerful and influential figure in the history of science fiction, and there’s no doubt that the genre would look entirely different if he were somehow lifted out of the picture. Yet while I never met Campbell, I’ve spoken with quite a few other magazine editors, and my sense is that it can be hard to think about reshaping the field when you’re mostly just concerned with getting out the current issue—or even with your very survival. The financial picture for science fiction magazines may have darkened over the last few decades, but it’s always been a challenge, and it can be difficult to focus on the short term while also keeping your larger objectives in mind. Campbell did it about as well as anyone ever did, but he was limited by the resources at his disposal, and he benefited from a few massive strokes of luck. I don’t think he would have had nearly the same impact if Heinlein hadn’t happened to show up within the first year and a half of his editorship, and you could say much the same of the fortuitous appearance of the artist Hubert Rogers. (By November 1940, Campbell could write: “Rogers has a unique record among science fiction artists: every time he does a cover, the author of the story involved writes him fan mail, and asks me for the cover original.”) In the end, it wasn’t the “astronomical” covers that improved the look of the magazine, but the arrival and development of unexpected talent. And much as Heinlein’s arrival on the scene was something that Campbell never could have anticipated, the advent of Rogers did more to heighten the visual element of Astounding than anything that the editor consciously set out to accomplish.

Campbell, typically, continued to think in terms of actively managing his magazines, and the pictorial results were the most dramatic, not in Astounding, but in Unknown, the legendary fantasy title that he launched in 1939. (His other great effort to tailor a magazine to his personal specifications involved the nonfiction Air Trails, which is a subject for another post.) Unlike Astounding, Unknown was a project that Campbell could develop from scratch, and he didn’t have to deal with precedents established by earlier editors. The resulting stories were palpably different from most of the other fantasy fiction of the time. (Algis Budrys, who calls Campbell “the great rationalizer of supposition,” memorably writes that the magazine was “more interested in the thermodynamics and contract law of a deal with the devil than with just what a ‘soul’ might actually be.”) But this also extended to the visual side. Campbell told his friend Robert Swisher that all elements, including page size, were discussed “carefully and without prejudice” with his publisher, and for the first year and a half, Unknown featured some of the most striking art that the genre had ever seen, with beautiful covers by H.W. Scott, Manuel Rey Isip, Modest Stein, Graves Gladney, and Edd Carter. But the editor remained dissatisfied, and on February 29, 1940, he informed Swisher of a startling decision:

We’re gonna pull a trick on Unknown presently. Probably the July issue will have no picture on the cover—just type. We have hopes of chiseling it outta the general pulp group, and having a few new readers mistake it for a different type. It isn’t straight pulp, and as such runs into difficulties because the adult type readers who might like it don’t examine the pulp racks, while the pulp-type reader in general wouldn’t get much out of it.

The italics are mine. Campbell had tried to appeal to “the adult type readers” by running more refined covers on Astounding, and with Unknown, his solution was to essentially eliminate the cover entirely. Writing to readers of the June 1940 issue to explain the change, the editor did his best to spin it as a reflection of the magazine’s special qualities:

Unknown simply is not an ordinary magazine. It does not, generally speaking, appeal to the usual audience of the standard-type magazine. We have decided on this experimental issue, because of this, in an effort to determine what other types of newsstand buyers might be attracted by a somewhat different approach.

In the next paragraph, Campbell ventured a curious argument: “To the nonreader of fantasy, to one who does not understand the attitude and philosophy of Unknown, the covers may appear simply monstrous rather than the semicaricatures they are. They are not, and have not been intended as, illustrations, but as expressive of a general theme.” Frankly, I doubt that many readers saw the covers as anything but straight illustrations, and in the following sentence, the editor made an assertion that seems even less plausible: “To those who know and enjoy Unknown, the cover, like any other wrapper, is comparatively unimportant.”

In a separate note, Campbell asked for feedback on the change, but he also made his own feelings clear: “We’re going to ask your newsdealer to display [Unknown] with magazines of general class—not with the newsprints. And we’re asking you—do you like the more dignified cover? Isn’t it much more fitting for a magazine containing such stories?” A few months later, in the October 1940 issue, a number of responses were published in the letters column. The reaction was mostly favorable—although Campbell may well have selected letters that supported his own views—but reasonable objections were also raised. One reader wrote: “How can you hope to win new readers by a different cover if the inside illustrations are as monstrous, if not more so, than have any previous covers ever been? If you are trying to be more dignified in your illustrations, be consistent throughout the magazine.” On a more practical level, another fan mentioned one possible shortcoming of the new approach: “The July issue was practically invisible among the other publications, and I had to hunt somewhat before I located it.” But it was too late. Unknown may have been the greatest pulp magazine of all time, but along the way, it rejected the entire raison d’être of the pulp magazine cover itself. And while I can’t speak for the readers of the time, I can say that it saddens me personally. Whenever I’m browsing through a box of old pulps, I feel a pang of disappointment when I come across one of the later Unknown covers, and I can only imagine what someone like Cartier might have done with Heinlein’s The Unpleasant Profession of Jonathan Hoag, or even Hubbard’s Fear. Unknown ran for another three years with its plain cover, which is about the same amount of time that it took for Astounding to reach its visual peak. It might have evolved into something equally wonderful, but we’ll never know—because Campbell decided that he had to kill the cover in order to save it.

The new mutation

Almost from the beginning, science fiction has had mixed feelings about the face that it presents to the world. The artwork that adorned the pulp magazines was the best form of advertising that it would ever have, and there were times when the covers seemed even more important than the contents, which could come across as an afterthought. (According to legend, Astounding itself owed its existence to a whim of the publisher William Clayton, who noticed one day that the huge sheet of paper on which the covers for his thirteen titles were printed—in four rows by four columns—had three blank spaces. Since the cover was the most expensive part, he could publish three more magazines at minimal cost, which was how the editor Harry Bates got the chance to pitch Astounding Stories of Super-Science. But this also tells you something about how the financial resources of the pulps were allocated.) To distinguish themselves from their competitors on the newsstands, these magazines naturally had to evolve bold colors and striking images, which is a big part of their appeal today. As long as they were content to be little more than disposable entertainment, that was perfectly fine, but after science fiction began to make claims for itself that were unlike those of other genre, the discrepancy between the packaging and the aspirations expressed on the inside began to seem like a problem. And this was a particular source of irritation for John W. Campbell, who came into the magazine with ambitions that strained against the confines of the medium, or at least the way in which it had always been marketed to its readers.

At first, Campbell even dreamed of replacing the name Astounding itself with the more refined Science Fiction, but he was frustrated by the debut of another pulp with that title the following year. He was busy trying to get better stories from his writers, but his first order of business was to improve the artwork, as he wrote to his friend Robert Swisher on October 24, 1937, just a few weeks after starting his new job:

Evolution proceeds by mutation—sudden small, but important changes developed through generations and tested before a new change is made. Ditto Astounding. The change in this case is going to be the cover: for some months, I’m going to try to run a series of covers that will be genuine artwork, first-class work with none of the lurid color idea that the mags have been using…I have vague, fond hopes that outsiders will be sufficiently interested in the cover to buy the magazine.

The use of the word “outsiders” was especially revealing. Campbell was looking to attract mainstream readers beyond his existing audience of fans, and he knew that the art—both inside and outside the magazine— had to make his case long before the stories ever could. As he wrote the following week to Swisher: “For the man who leafs through that curious and new-to-him magazine, Astounding Stories, nice, clean-cut illustrations in careful reproduction mean a lot. He can’t get the quality of the stories till he’s bought the thing once—the pictures have to sell it to him.”

In the meantime, though, Campbell had to sell his proposed changes to his current readers, for whom the artwork had always been a positive attraction. Writing in an unsigned editorial in the February 1938 issue, which bore a refined painting of the surface of Mercury, he laid out his reasoning in terms that he hoped would appeal to fans:

That cover is the first of a series—a new mutant field opened to science fiction. It illustrates Raymond Z. Gallun’s story “Mercutian Adventure,” but more than that; it is an accurate astronomical color-plate. You noticed there was no text, no printed matter on the picture itself? There will be none on the astronomical plates to follow. Each will be, as is this, an accurate a representation of some other-world scene as modern astronomical knowledge and the complex psychology and physics of human vision make possible.

Campbell emphasized the hard work that had gone into the painting: “Howard Brown and I worked over this cover, I trying to get the astronomy accurate; Brown, helping in the more difficult work of interpretation of fact to human understanding.” He noted that the cover actually depicted the sun as larger than it would appear from Mercury in real life, which reflected the fact that human vision tended to perceive astronomical objects as greater than their true size. And he concluded: “Our astronomical color plate covers will be as accurate an impression as astronomical science and knowledge of human reaction can make them.”

I don’t know what Campbell and Brown actually discussed, but my hunch is that the conversation was slightly more pragmatic than what the editor described here. The real issue, I suspect, was that a depiction of the sun in its true proportions wouldn’t have been striking enough to catch the eye of a casual browser at a candy store. But Campbell’s rationalization—which combines an appeal to accuracy with the need to reflect “human understanding”—is noteworthy in itself. For years, he would struggle to reconcile his hopes for the genre with the realities of the pulps, which resulted in some of the most fascinating aspects of the golden age of science fiction. (I could write an entire post, and maybe I will, about the cover typography alone. Campbell repeatedly tinkered with the magazine’s logo, including one version that I love so much that I quietly appropriated it for my own book, but it wasn’t until after World War II that he was able to alter it so that the word Astounding appeared in barely legible script over the bold Science Fiction, allowing him to effectively pull off the title change that he had wanted since the late thirties.) Over the following three years, the “astronomical” covers would continue to appear at irregular intervals, alternating with traditional pulp paintings, many of which were undeniably crude. Yet the more conventional artwork was improving as well. Charles Schneeman’s cover for “The Merman” in the December 1938 issue, which coincided with a gorgeous new logo, was an undeniable step forward, and the process culminated two months later with the debut of Hubert Rogers. Tomorrow, I’ll consider how the covers continued to evolve, and how the ultimate result was far more wonderful than even Campbell could have anticipated.

The mystical vision

If I have one regret about Astounding, which is generally a book that I’m proud to have written, it’s that it doesn’t talk much about the illustrators who played such an important role in the development of modern science fiction. If I had to justify this omission, I would offer three excuses, none of which is particularly convincing on its own. The first is that it’s impossible to discuss this subject at any length without a lot of pictures, preferably in color. My budget for images—both for obtaining rights and for the physical process of printing—was extremely constrained, and there are plenty of existing books out there that are filled with beautiful reproductions. The second is that this was primarily a story about John W. Campbell and his circle of writers, and there just wasn’t as much narrative material for the artists. (As Frank Kelly Freas once said: “There are fewer tales about [Campbell’s] artists only because there have been fewer artists—it took a certain amount of resiliency in an artist to keep from being worn down to a mere nub on the grinding wheel of the Campbell brilliance.”) And the third is that this was already a big book that had to include biographies of four complex individuals and the people in their lives, a critical look at their work, and a history of science fiction for the period as a whole. I was building up much of this expertise from scratch, and even in the finished product, there are times when the various strands barely manage to hold together. Something had to give along the way, and without a lot of conscious thought, I suspect that I made the call to pass lightly over the artists, just for the sake of keeping this book within reasonable bounds.

Yet it also leaves a real gap in the story, and I’m keenly aware of its absence. If nothing else, the artwork of the classic pulps—particularly their painted covers—played a huge role in attracting readers, including many who went on to become authors themselves. In his memoir In Memory Yet Green, Isaac Asimov recounts how the sight of the magazines in his family’s candy store filled him with longing, and how the illustrations played a significant role in his fateful effort to secure his father’s permission to read them:

I picked up [Science Wonder Stories] and, not without considerable qualms, approached my formidable sire…I spoke rapidly, pointed out the word “science,” showed him the paintings of futuristic machines inside as an indication of how advanced it was, and (I believe) made it plain that if he said “No,” I had every intention of mounting a rebellion.

The italics are mine. From the very beginning, the visual element of science fiction has served as a priceless form of free advertising, both for individual fans and for the culture as a whole. These images shaped our collective notion of the genre as much as the words did, if not more, and it’s a large part of the reason why Amazing Stories, not Astounding, became the primary reference point for the likes of Steven Spielberg and George Lucas. You can still browse through those covers with pleasure, and I honestly dare you to do the same with a randomly selected story. And if Amazing still inspires some of our most extravagant dreams, it isn’t because of the words.

You could also argue that the collaboration between artists and writers—which usually took place without the two sides ever interacting—was more responsible for what science fiction became than either half could be on its own. (This is a decent reason, by the way, for seeking out reproductions of the original magazine pages whenever possible. In practice, the stories tend to be anthologized in one place, while the illustrations are collected in another, which presents a fragmented picture of how fans experienced the genre in real time.) In the earliest period, the connection between text and image was extremely close, to the point that many of the illustrations had captions to let you know exactly what moment was being depicted. As Brian Aldiss writes in the lavish book Science Fiction Art:

[Artist Frank R. Paul] appears rather pedestrian in his approach; his objective seems to be merely to translate as literally as possible the words of the writer into pictures, as if he were translating from one language into another. Moreover, in the Gernsback magazines, he was often anchored to the literal text, a line or two of which would be appended under the illustration in an old-fashioned way.

Yet it only takes a second to realize that this is only part of the story. Paul may have been translating words into images, but he was also expanding, elaborating, and improving on his raw material. As Aldiss continues: “[Paul’s] creed, one might suspect, was utilitarian. Yet an almost mystical vision shines forth from his best covers.” And it certainly wasn’t there in most stories.

“Paul made amends for the inadequacies of the writers,” Aldiss concludes, and it’s hard not to agree. In One Hundred Years of Science Fiction Illustration, Anthony Frewin elaborates:

Paul had little or no precedent from which to gain inspiration and it is a fitting tribute to his incredible imagination that his vision and stylization of SF would characterize all similar work for the next forty years. Paul, when illustrating a story, created these monstrous galactic cities, alien landscapes, and mechanical behemoths entirely himself—the descriptions contained in the stories were never ever much more specific than, for example, something like “shimmering towers rising into the clouds from a crystal-like terrain.” He had a bias for the epic conception and many of his best covers depict vast vistas with vanishing point perspective which, nonetheless, still had a painstaking and elaborate attention to the smallest detail that one could equate with the work of John Martin.

And what was especially true of Paul was true of science fiction illustration in general. So much of what we associate with the genre—its scale, its galactic expanses, its sense of wonder—was best expressed in pictures. (It’s even possible that a writer like Asimov could get away with barely sketching in the visual aspects of his stories because he knew that Hubert Rogers would take it from there.) “Many of us began reading SF ‘because of the pictures,’” Aldiss writes, and in the end, its pictures may be its most lasting legacy. Over the next few days, I’ll be taking a closer look at what this means.

Note: I’ll be holding a Reddit AMA today at 12:30pm ET on /r/books to talk about Astounding and the golden age of science fiction. I hope that some of you can make it!

The Thing from Another Manuscript

On March 2, 1966, Howard Applegate, the administrator of manuscripts at Syracuse University, wrote to the editor John W. Campbell to ask if he’d be interested in donating his papers to their archives. Two weeks later, Campbell replied:

Sorry…but the Harvard Library got all the old manuscripts I had about eight years ago! Since I stopped writing stories when I became editor of Astounding/Analog, I haven’t produced any manuscripts since 1938…So…sorry, but any scholarly would-be biographers are going to have a tough time finding any useful documentation on me! I just didn’t keep the records!

Fortunately for me, this turned out to be far from the case, and I was only able to read these words in the first place because of diligent fans and archivists—notably the late Perry Chapdelaine—who had done what they could to preserve Campbell’s correspondence. When I came across his exchange with Applegate, in fact, I was busy working through thousands of pages of the editor’s surviving letters, which provided the indispensable foundation for my book Astounding. But the reference to Harvard surprised me. At that point, I had been working on this project for close to a year, and I had never heard the slightest whisper about a collection of his manuscripts in Cambridge. (I subsequently realized that Campbell had referred to it in passing to the fan Robert Swisher in a letter dated October 7, 1955, but I didn’t notice this until much later.)

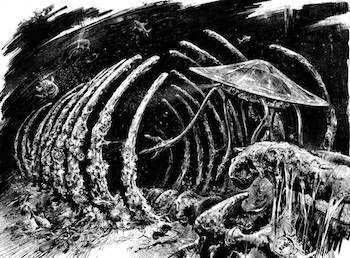

When I looked into it further, nothing came up in a casual search online, but I finally found an entry for it buried deep in the catalog for Houghton Library. (I’ve never seen it mentioned anywhere else, not even in scholarly works on science fiction, which implies that the papers were sent to Harvard and then promptly forgotten.) The description was intriguing, but I had plenty to do in the meantime, and I didn’t have a chance to follow up on it until last September, when I sent a request for more information through the library’s query system. About a week later, I heard back from a very helpful librarian, who had taken the time to examine the carton and send me a list of the labels on the folders inside. There were about fifty in all, and while most bore the titles of stories or articles that I recognized—“Out of Night,” “The Elder Gods,” The Moon is Hell—there were quite a few that were unfamiliar to me. I was particularly interested in the folder labeled “Frozen Hell,” which I knew from Campbell’s correspondence had been the original title of “Who Goes There?”, the classic novella that was adapted three times for the movies as The Thing. At that point, I knew that I had to check it out, if only because I didn’t want to get scooped by anybody else, and although I wasn’t able to travel to Cambridge in person, I managed to hire a research assistant to go to the library and scan the pages on my behalf. She did a brilliant job, and after a few rounds of visits, I had copies of everything that I needed. As I had hoped, there was a lot of great stuff in that box, including previously unpublished works by Campbell and the only known story credited to his remarkable wife Doña, which I hope to discuss here in depth one day. But the very first file that I opened was the one called “Frozen Hell.”

When I sat down to read these pages, I was mostly just hoping to get some insight into the writing of “Who Goes There?”, which has been rightly ranked as the greatest science fiction suspense story of all time. But what I found there was so remarkable that I still can’t quite believe it myself. “Who Goes There?” is famously about an Antarctic research expedition that stumbles across a hideous extraterrestrial buried in the ice, and as it originally appeared in Astounding Science Fiction in 1938, the novella opens with the alien’s body already back at the base, with everything that happened beforehand—the magnetic anomaly that led the team to the site, the uncovering of the spaceship, and its accidental destruction—recounted in dialogue. In the draft of “Frozen Hell” that was preserved in Campbell’s papers, it’s narrated in detail from the beginning, with a huge forty-five page opening section, never before published, about the discovery of the spacecraft itself. (Apart from a few plot points and character names, the rest tracks the established version fairly closely, although there are some interesting surprises and variations.) We know that Campbell discussed the story with the editors F. Orlin Tremaine and Frank Blackwell, and at some point, they evidently decided that most of this material should be cut or integrated elsewhere. Judging from the other manuscripts that I found at Harvard, Campbell often cut the beginnings from his stories, which reflected the advice that he later gave to other writers, including Isaac Asimov, that you should enter the story as late as possible. But when you restore this material, which is written on the same high level as the rest, you end up with something fascinating—a story that shifts abruptly from straight adventure into horror. This is the kind of structure that I love, and there’s something very modern about the way in which it switches genres halfway through.

The result amounted to an entirely different version, and a completely worthwhile one, of one of the most famous science fiction stories ever written, which had been waiting there at Harvard all this time. As far as I can tell, no one else ever knew that it existed, and the more I thought about its potential, the more excited I became. I began by reaching out to Campbell’s daughter Leslyn, whom I had gotten to know through working on his biography, and she referred me in turn to John Gregory Betancourt, the writer and editor who manages the estate. John agreed that it was worth publishing, and he ultimately decided to release it through his own imprint, Wildside Press, in a special edition funded through a campaign on Kickstarter. The result went live last week, with a goal of raising $1,000, and it quickly blew past everyone’s expectations. As I type this, its pledges have exceeded $27,000, and it shows no sign of stopping. (Andrew Liptak of The Verge had a nice writeup about the project, which seems to have helped, and word of mouth is still spreading.) At the moment, the package will include an introduction by Robert Silverberg, original fiction by Betancourt and G.D. Falksen, and cover and interior illustrations by Bob Eggleton, with more features to follow as it reaches its stretch goals. I’ll be contributing a preface in which I’ll talk more about the manuscript, Campbell’s writing process, and some of the variant openings that were also preserved in his papers. Publication is scheduled for early next year, and I’m hoping to have more updates soon—although I’m already thrilled beyond measure by the response so far. Astounding comes out tomorrow, and I’m obviously curious about what its reception will be. There are some big developments just around the corner. But I wouldn’t be surprised if Frozen Hell ends up being the best thing to come out of this entire project.

The Machine of Lagado

Yesterday, my wife wrote to me in a text message: “Psychohistory could not predict that Elon [Musk] would gin up a fraudulent stock buyback price based on a pot joke and then get punished by the SEC.” This might lead you to wonder about our texting habits, but more to the point, she was right. Psychohistory—the fictional science of forecasting the future developed by Isaac Asimov and John W. Campbell in the Foundation series—is based on the assumption that the world will change in the future more or less as it has in the past. Like all systems of prediction, it’s unable to foresee black swans, like the Mule or Donald Trump, that make nonsense of our previous assumptions, and it’s useless for predicting events on a small scale. Asimov liked to compare it to the kinetic theory of gases, “where the individual molecules in the gas remain as unpredictable as ever, but the average person is completely predictable.” This means that you need a sufficiently large number of people, such as the population of the galaxy, for it to work, and it also means that it grows correspondingly less useful as it becomes more specific. On the individual level, human behavior is as unforeseeable as the motion of particular molecules, and the shape of any particular life is impossible to predict, even if we like to believe otherwise. The same is true of events. Just as a monkey or a dartboard might do an equally good job of picking stocks as a qualified investment advisor, the news these days often seems to have been generated by a bot, like the Subreddit Simulator, that automatically cranks out random combinations of keywords and trending terms. (My favorite recent example is an actual headline from the Washington Post: “Border Patrol agent admits to starting wildfire during gender-reveal party.”)

And the satirical notion that combining ideas at random might lead to useful insights or predictions is a very old one. In Gulliver’s Travels, Jonathan Swift describes an encounter with a fictional machine—located in the academy of Lagado, the capital city of the island of Balnibarbi—by which “the most ignorant person, at a reasonable charge, and with a little bodily labour, might write books in philosophy, poetry, politics, laws, mathematics, and theology, without the least assistance from genius or study.” The narrator continues:

[The professor] then led me to the frame, about the sides, whereof all his pupils stood in ranks. It was twenty feet square, placed in the middle of the room. The superfices was composed of several bits of wood, about the bigness of a die, but some larger than others. They were all linked together by slender wires. These bits of wood were covered, on every square, with paper pasted on them; and on these papers were written all the words of their language, in their several moods, tenses, and declensions; but without any order…The pupils, at his command, took each of them hold of an iron handle, whereof there were forty fixed round the edges of the frame; and giving them a sudden turn, the whole disposition of the words was entirely changed. He then commanded six-and-thirty of the lads, to read the several lines softly, as they appeared upon the frame; and where they found three or four words together that might make part of a sentence, they dictated to the four remaining boys, who were scribes.

And Gulliver concludes: “Six hours a day the young students were employed in this labour; and the professor showed me several volumes in large folio, already collected, of broken sentences, which he intended to piece together, and out of those rich materials, to give the world a complete body of all arts and sciences.”

Two and a half centuries later, an updated version of this machine figured in Umberto Eco’s novel Foucault’s Pendulum, which is where I first encountered it. The book’s three protagonists, who work as editors for a publishing company in Milan, are playing in the early eighties with their new desktop computer, which they’ve nicknamed Abulafia, after the medieval cabalist. One speaks proudly of Abulafia’s usefulness in generating random combinations: “All that’s needed is the data and the desire. Take, for example, poetry. The program asks you how many lines you want in the poem, and you decide: ten, twenty, a hundred. Then the program randomizes the line numbers. In other words, a new arrangement each time. With ten lines you can make thousands and thousands of random poems.” This gives the narrator an idea:

What if, instead, you fed it a few dozen notions taken from the works of [occult writers]—for example, the Templars fled to Scotland, or the Corpus Hermeticum arrived in Florence in 1460—and threw in a few connective phrases like “It’s obvious that” and “This proves that?” We might end up with something revelatory. Then we fill in the gaps, call the repetitions prophecies, and—voila—a hitherto unpublished chapter of the history of magic, at the very least!

Taking random sentences from unpublished manuscripts, they enter such lines as “Who was married at the feast of Cana?” and “Minnie Mouse is Mickey’s fiancee.” When strung together, the result, in one of Eco’s sly jokes, is a conspiracy theory that exactly duplicates the thesis of Holy Blood, Holy Grail, which later provided much of the inspiration for The Da Vinci Code. “Nobody would take that seriously,” one of the editors says. The narrator replies: “On the contrary, it would sell a few hundred thousand copies.”