Archive for the ‘Movies’ Category

Quote of the Day

When the system doesn’t respond, when it doesn’t accept what you’re doing—and most of the time it won’t—you have a chance to become self-reliant and create your own system. There will always be periods of solitude and loneliness, but you must have the courage to follow your own path. Cleverness on the terrain is the most important trait of a filmmaker.

Always take the initiative. There is nothing wrong with spending a night in a jail cell if it means getting the shot you need. Send out all your dogs and one might return with prey. Beware of the cliché. Never wallow in your troubles; despair must be kept private and brief. Learn to live with your mistakes. Study the law and scrutinize contracts. Expand your knowledge and understanding of music and literature, old and modern. Keep your eyes open. That roll of unexposed celluloid you have in your hand might be the last in existence, so do something impressive with it. There is never an excuse not to finish a film. Carry bolt cutters everywhere.

Thwart institutional cowardice. Ask for forgiveness, not permission. Take your fate into your own hands. Don’t preach on deaf ears. Learn to read the inner essence of a landscape. Ignite the fire within and explore unknown territory. Walk straight ahead, never detour. Learn on the job. Maneuver and mislead, but always deliver. Don’t be fearful of rejection. Develop your own voice. Day one is the point of no return. Know how to act alone and in a group. Guard your time carefully. A badge of honor is to fail a film theory class. Chance is the lifeblood of cinema. Guerrilla tactics are best. Take revenge if need be. Get used to the bear behind you. Form clandestine rogue cells everywhere.

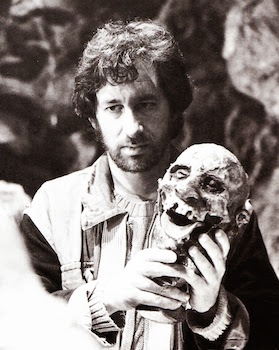

The temple of doom

Note: I’m taking some time off for the holidays, so I’m republishing a few pieces from earlier in this blog’s run. This post originally appeared, in a slightly different form, on January 27, 2017.

I think America is going through a paroxysm of rage…But I think there’s going to be a happy ending in November.

—Steven Spielberg, to Sky News, July 17, 2016

Last week, in an interview with the New York Times about the twenty-fifth anniversary of Schindler’s List and the expansion of the mission of The Shoah Foundation, Steven Spielberg said of this historical moment:

I think there’s a measurable uptick in anti-Semitism, and certainly an uptick in xenophobia. The racial divide is bigger than I would ever imagine it could be in this modern era. People are voicing hate more now because there’s so many more outlets that give voice to reasonable and unreasonable opinions and demands. People in the highest places are allowing others who would never express their hatred to publicly express it. And that’s been a big change.

Spielberg, it’s fair to say, remains the most quintessentially American of all directors, despite a filmography that ranges freely between cultures and seems equally comfortable in the past and in the future. He’s often called a mythmaker, and if there’s a place where his glossy period pieces, suburban landscapes, and visionary adventures meet, it’s somewhere in the nation’s collective unconscious: its secret reveries of what it used to be, what it is, and what it might be again. Spielberg country, as Stranger Things was determined to remind us, is one of small towns and kids on bikes, but it also still vividly remembers how it beat the Nazis, and it can’t resist turning John Hammond from a calculating billionaire into a grandfatherly, harmless dreamer. No other artist of the last half century has done so much to shape how we all feel about ourselves. He took over where Walt Disney left off. But what has he really done?

To put it in the harshest possible terms, it’s worth asking whether Spielberg—whose personal politics are impeccably liberal—is responsible in part for our current predicament. He taught the New Hollywood how to make movies that force audiences to feel without asking them to think, to encourage an illusion of empathy instead of the real thing, and to create happy endings that confirm viewers in their complacency. You can’t appeal to all four quadrants, as Spielberg did to a greater extent than anyone who has ever lived, without consistently telling people exactly what they want to hear. I’ve spoken elsewhere of how film serves as an exercise ground for the emotions, bringing us closer on a regular basis to the terror, wonder, and despair that many of us would otherwise experience only rarely. It reminds the middle class of what it means to feel pain or awe. But I worry that when we discharge these feelings at the movies, it reduces our capacity to experience them in real life, or, even more insidiously, makes us think that we’re more empathetic and compassionate than we actually are. Few movies have made viewers cry as much as E.T., and few have presented a dilemma further removed than anything a real person is likely to face. (Turn E.T. into an illegal alien being sheltered from a government agency, maybe, and you’d be onto something.) Nearly every film from the first half of Spielberg’s career can be taken as a metaphor for something else. But great popular entertainment has a way of referring to nothing but itself, in a cognitive bridge to nowhere, and his images are so overwhelming that it can seem superfluous to give them any larger meaning.

If Spielberg had been content to be nothing but a propagandist, he would have been the greatest one who ever lived. (Hence, perhaps, his queasy fascination with the films of Leni Riefenstahl, who has affinities with Spielberg that make nonsense out of political or religious labels.) Instead, he grew into something that is much harder to define. Jaws, his second film, became the most successful movie ever made, and when he followed it up with Close Encounters, it became obvious that he was in a position with few parallels in the history of art—he occupied a central place in the culture and was also one of its most advanced craftsmen, at a younger age than Damien Chazelle is now. If you’re talented enough to assume that role and smart enough to stay there, your work will inevitably be put to uses that you never could have anticipated. It’s possible to pull clips from Spielberg’s films that make him seem like the cuddliest, most repellent reactionary imaginable, of the sort that once prompted Tony Kushner to say:

Steven Spielberg is apparently a Democrat. He just gave a big party for Bill Clinton. I guess that means he’s probably idiotic…Jurassic Park is sublimely good, hideously reactionary art. E.T. and Close Encounters of the Third Kind are the flagship aesthetic statements of Reaganism. They’re fascinating for that reason, because Spielberg is somebody who has just an astonishing ear for the rumblings of reaction, and he just goes right for it and he knows exactly what to do with it.

Kushner, of course, later became Spielberg’s most devoted screenwriter. And the total transformation of the leading playwright of his generation is the greatest testament imaginable to this director’s uncanny power and importance.

In reality, Spielberg has always been more interesting than he had any right to be, and if his movies have been used to shake people up in the dark while numbing them in other ways, or to confirm the received notions of those who are nostalgic for an America that never existed, it’s hard to conceive of a director of his stature for whom this wouldn’t have been the case. To his credit, Spielberg clearly grasps the uniqueness of his position, and he has done what he could with it, in ways that can seem overly studied. For the last two decades, he has worked hard to challenge some of our assumptions, and at least one of his efforts, Munich, is a masterpiece. But if I’m honest, the film that I find myself thinking about the most is Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. It isn’t my favorite Indiana Jones movie—I’d rank it a distant third. For long stretches, it isn’t even all that good. It also trades in the kind of casual racial stereotyping that would be unthinkable today, and it isn’t any more excusable because it deliberately harks back to the conventions of an earlier era. (The fact that it’s even watchable now only indicates how much ground East and South Asians have yet to cover.) But its best scenes are so exciting, so wonderful, and so conductive to dreams that I’ve never gotten over it. Spielberg himself was never particularly pleased with the result, and if asked, he might express discomfort with some of the decisions he made. But there’s no greater tribute to his artistry, which executed that misguided project with such unthinking skill that he exhilarated us almost against his better judgment. It tells us how dangerous he might have been if he hadn’t been so deeply humane. And we should count ourselves lucky that he turned out to be as good of a man as he did, because we’d never have known if he hadn’t.

The fairy tale theater

It must have all started with The Princess Switch, although that’s so long ago now that I can barely remember. Netflix was pushing me hard to watch an original movie with Vanessa Hudgens in a dual role as a European royal and a baker from Chicago who trade places and end up romantically entangled with each other’s love interests at Christmas, and I finally gave in. In the weeks since, my wife and I have watched Pride, Prejudice, and Mistletoe; The Nine Lives of Christmas; Crown for Christmas; The Holiday Calendar; Christmas at the Palace; and possibly one or two others that I’ve forgotten. A few were on Netflix, but most were on Hallmark, which has staked out this space so aggressively that it can seem frighteningly singleminded in its pursuit of Yuletide cheer. By now, it airs close to forty original holiday romances between Thanksgiving and New Year’s Eve, and like its paperback predecessors, it knows better than to tinker with a proven formula. As two of its writers anonymously reveal in an interview with Entertainment Weekly:

We have an idea and it maybe takes us a week or so just to break it down into a treatment, a synopsis of the story; it’s like a beat sheet where you pretty much write what’s going to happen in every scene you just don’t write the scene. If we have a solid beat sheet done and it’s approved, then it’s only going to take us about a week and a half to finish a draft. Basically, an act or two a day and there’s nine. They’re kind of simple because there are so many rules so you know what you can and can’t do, and if you have everything worked out it comes together.

And the rules are revealing in themselves. As one writer notes: “The first rule is snow. We really wanted to do one where the basic conflict was a fear that there will not be snow on Christmas. We were told you cannot do that, there must be snow. They can’t be waiting for the snow, there has to be snow. You cannot threaten them with no snow.” And the conventions that make these movies so watchable are built directly into the structure:

There cannot be a single scene that does not acknowledge the theme. Well, maybe a scene, but you can’t have a single act that doesn’t acknowledge it and there are nine of them, so there’s lots of opportunities for Christmas. They have a really rigid nine-act structure that makes writing them a lot of fun because it’s almost like an exercise. You know where you have to get to: People have to be kissing for the first time, probably in some sort of a Christmas setting, probably with snow falling from the sky, probably with a small crowd watching. You have to start with two people who, for whatever reason, don’t like each other and you’re just maneuvering through those nine acts to get them to that kiss in the snow.

The result, as I’ve learned firsthand, is a movie that seems familiar before you’ve even seen it. You can watch with one eye as you’re wrapping presents, or tune in halfway through with no fear of becoming confused. It allows its viewers to give it exactly as much attention as they’re willing to spare, and at a time when the mere act of watching prestige television can be physically exhausting, there’s something to be said for an option that asks nothing of us at all.

After you’ve seen two or three of these movies, of course, the details start to blur, particularly when it comes to the male leads. The writers speak hopefully of making the characters “as unique and interesting as they can be within the confines of Hallmark land,” but while the women are allowed an occasional flash of individuality, the men are unfailingly generic. This is particularly true of the subgenre in which the love interest is a king or prince, who doesn’t get any more personality than his counterpart in fairy tales. Yet this may not be a flaw. In On Directing Film, which is the best work on storytelling that I’ve ever read, David Mamet provides a relevant word of advice:

In The Uses of Enchantment, Bruno Bettelheim says of fairy tales the same thing Alfred Hitchcock said about thrillers: that the less the hero of the play is inflected, identified, and characterized, the more we will endow him with our own internal meaning—the more we will identify with him—which is to say the more we will be assured that we are that hero. “The hero rode up on a white horse.” You don’t say “a short hero rode up on a white horse,” because if the listener isn’t short he isn’t going to identify with that hero. You don’t say “a tall hero rode up on a white horse,” because if the listener isn’t tall, he won’t identify with the hero. You say “a hero,” and the audience subconsciously realize they are that hero.

Yet Mamet also overlooks the fact that the women in fairy tales, like Snow White, are often described with great specificity—it’s the prince who is glimpsed only faintly. Hallmark follows much the same rule, which implies that it’s less important for the audience to identify with the protagonist than to fantasize without constraint about the object of desire.

This also leads to some unfortunate decisions about diversity, which is more or less what you might expect. As one writer says candidly to Entertainment Weekly:

On our end, we just write everybody as white, we don’t even bother to fight that war. If they want to put someone of color in there, that would be wonderful, but we don’t have control of that…I found out Meghan Markle had been in some and she’s biracial, but it almost seems like they’ve tightened those restrictions more recently. Everything’s just such a white, white, white, white world. It’s a white Christmas after all—with the snow and the people.

With more than thirty original movies coming out every year, you might think that Hallmark could make a few exceptions, especially since the demand clearly exists, but this isn’t about marketing at all. It’s a reflection of the fact that nonwhiteness is still seen as a token of difference, or a deviation from an assumed norm, and it’s the logical extension of the rules that I’ve listed above. White characters have the privilege—which is invisible but very real—of seeming culturally uninflected, which is the baseline that allows the formula to unfold. This seems very close to John W. Campbell’s implicit notion that all characters in science fiction should be white males by default, and while other genres have gradually moved past this point, it’s still very much the case with Hallmark. (There can be nonwhite characters, but they have to follow the rules: “Normally there’ll be a black character that’s like a friend or a boss, usually someone benevolent because you don’t want your one person of color to not be positive.”) With diversity, as with everything else, Hallmark is very mindful of how much variation its audience will accept. It thinks that it knows the formula. And it might not even be wrong.

Quote of the Day

The way you people make movies is you start with character and build outward. I start with construction and then fill it in.

—Brian De Palma, in the documentary De Palma

The long night

Three years ago, a man named Paul Gregory died on Christmas Day. He lived by himself in Desert Hot Springs, California, where he evidently shot himself in his apartment at the age of ninety-five. His death wasn’t widely reported, and it was only this past week that his obituary appeared in the New York Times, which noted of his passing:

Word leaked out slowly. Almost a year later, The Desert Sun, a daily newspaper serving Palm Springs, California, and the Coachella Valley area, published an article that took note of Mr. Gregory’s death, saying that “few people knew about it.” “He wasn’t given a public memorial service and he didn’t receive the kind of appreciations showbiz luminaries usually get,” the newspaper said…When the newspaper’s article appeared, [the Desert Hot Springs Historical Society] had recently given a dinner in Mr. Gregory’s memory for a group of his friends. “His passing was so quiet,” Bruce Fessler, who wrote the article, told the gathering. “No one wrote about him. It’s just one of those awkward moments.”

Yet his life was a remarkable one, and more than worth a full biography. Gregory was a successful film and theater producer who crossed paths over the course of his career with countless famous names. On Broadway, he was the force behind Herman Wouk’s The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial, one of the big dramatic hits of its time, and he produced Laughton’s The Night of the Hunter, which deserves to be ranked among the greatest American movies.

Gregory’s involvement with The Night of the Hunter alone would have merited a mention here, but his death caught my eye for other reasons. As I mentioned here last week, I’ve slowly been reading through Mailer’s Selected Letters, in which both Gregory and Laughton figure prominently. In 1954, Mailer told his friends Charlie and Jill Devlin that he had recently received an offer from Gregory, whom he described as “a kind of front for Charles Laughton,” for the rights to The Naked and the Dead. He continued:

Now, about two weeks ago Gregory called me up for dinner and gave me the treatment. Read Naked five times, he said, loved it, those Marines, what an extraordinary human story of those Marines, etc…What he wants to do, he claims, is have me do an adaptation of Naked, not as a play, but as a dramatized book to be put on like The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial…Anyway, he wants it to be me and only me to do the play version.

The play never got off the ground, but Gregory retained the movie rights to the novel, with an eye to Laughton directing with Robert Mitchum in the lead. Mailer was hugely impressed by Laughton, telling Elsa Lanchester decades later that he had never met “an actor before or since whose mind was so fine and powerful” as her late husband’s. The two men spent a week at Laughton’s hotel in Switzerland going over the book, and Mailer recalled that the experience was “a marvelous brief education in the problems of a movie director.”

In the end, sadly, this version of the movie was never made, and Mailer deeply disliked the film that Gregory eventually produced with director Raoul Walsh. It might all seem like just another footnote to Mailer’s career—but there’s another letter that deserves to be mentioned. At exactly the same time that Mailer was negotiating with Gregory, he wrote an essay titled “The Homosexual Villain,” in which he did the best that he could, given the limitations of his era and his personality, to come to terms with his own homophobia. (Mailer himself never cared for the result, and it’s barely worth reading today even as a curiosity. The closing line gives a good sense of the tone: “Finally, heterosexuals are people too, and the hope of acceptance, tolerance, and sympathy must rest on this mutual appreciation.”) On September 24, 1954, Mailer wrote to the editors of One: The Homosexual Magazine, in which the article was scheduled to appear:

Now, something which you may find somewhat irritating. And I hate like hell to request it, but I think it’s necessary. Perhaps you’ve read in the papers that The Naked and the Dead has been sold to Paul Gregory. It happens to be half-true. He’s in the act of buying it, but the deal has not yet been closed. For this reason I wonder if you could hold off publication for a couple of months? I don’t believe that the publication of this article would actually affect the sale, but it is a possibility, especially since Gregory—shall we put it this way—may conceivably be homosexual.

And while there’s a lot to discuss here, it’s worth emphasizing the casual and utterly gratuitous way in which Mailer—who became friendly years later with Roy Cohn—outed his future business partner by name.

But the letter also inadvertently points to a fascinating and largely unreported aspect of Gregory’s life, which I can do little more than suggest here. Charles Laughton, of course, was gay, as Elsa Lanchester discusses at length in her autobiography. (Gregory appears frequently in this book as well. He evidently paid a thousand dollars to Confidential magazine to kill a story about Laughton’s sexuality, and Lanchester quotes a letter from Gregory in which he accused Henry Fonda, who appeared in The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial, of calling Laughton a “fat, ugly homosexual”—although Laughton told her that Fonda had used an even uglier word.) Their marriage was obviously a complicated one, but it was far from the only such partnership. The actress Mary Martin, best known for her role as Peter Pan, was married for decades to the producer and critic Richard Halliday, whom her biographer David Kaufman describes as “her father, her husband, her best friend, her gay/straight ‘cover,’ and, both literally and figuratively, her manager.” One of Martin’s closest friends was Janet Gaynor, the Academy Award-winning actress who played the lead in the original version of A Star is Born. Gaynor was married for many years to Gilbert Adrian, an openly gay costume designer whose most famous credit was The Wizard of Oz. Gaynor herself was widely believed to be gay or bisexual, and a few years after Adrian’s death, she married a second time—to Paul Gregory. Gaynor and Gregory often traveled with Martin, and they were involved in a horrific taxi accident in San Francisco in 1982, in which Martin’s manager was killed, Gregory broke both legs, Martin fractured two ribs and her pelvis, and Gaynor sustained injuries that led to her death two years later. Gregory remarried, but his second wife passed away shortly afterward, and he appears to have lived quietly on his own until his suicide three years ago. The rest of the world only recently heard about his death. But even if we don’t know the details, it seems clear that there were many stories from his life that we’ll never get to hear at all.

Quote of the Day

A tip from Lubitsch: Let the the audience add up two plus two. They’ll love you forever.

—Billy Wilder, to Cameron Crowe in Conversations with Wilder

Which lie did he tell?

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid is, no question, the most popular thing I’ve ever been connected with. When I die, if the Times gives me an obit, it’s going to be because of Butch.

—William Goldman, The Princess Bride

When William Goldman passed away last week, I had the distinct sense that the world was mourning three different men. One was the novelist whose most lasting work will certainly end up being The Princess Bride; another was the screenwriter who won Academy Awards for Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and All the President’s Men; and a third was the Hollywood insider who wrote the indispensable books Adventures in the Screen Trade and Which Lie Did I I Tell? I’ll miss all three of them, and there’s no question that they led a deeply interconnected existence, but it’s the last one who might have had the greatest impact on my life. Goldman’s books on the movie industry are two of the great reads of all time, and I revisit them both every couple of years for the sheer pleasure that they offer me. (His book about Broadway, The Season, is equally excellent, although I lent my copy to a friend over a decade ago and never got it back.) They’re also some of the best books on writing ever published, and although Goldman cautions against applying their insights to other kinds of fiction, I often find myself drawing on his advice. Between the two, I prefer Which Lie Did I I Tell?, even through it chronicles a period in the author’s career in which he didn’t produce any memorable movies, apart from the significant exception of The Princess Bride itself. In fact, these books are fascinating largely because Goldman is capable of mining as many insights, if not more, from Absolute Power and The Ghost and the Darkness as he is from Butch Cassidy. One possible takeaway might be that there’s a similarly interesting story behind every movie, and that it’s unfortunate that they don’t all have chroniclers as eloquent and candid as Goldman. But it’s also a testament to his talent as a writer, which was to take some of the most challenging forms imaginable and make them seem as natural as breathing, even if that impression was an act of impersonation in itself.

When I look back at this blog, I discover that I’ve cited Goldman endlessly on all kinds of topics. My favorite passage from Which Lie Did I Tell?, which I quoted in one of my earliest posts, is a story that he relates about somebody else:

One of the great breaks of my career came in 1960, when I was among those called in to doctor a musical in very deep trouble, Tenderloin. The show eventually was not a success. But the experience was profound. George Abbott, the legitimately legendary Broadway figure, was the director of the show—he was closing in on seventy-five during our months together and hotter than ever…He was coming from backstage during rehearsals, and as he crossed the stage into the auditorium he noticed a dozen dancers were just standing there. The choreographer sat in the audience alone, his head in his hands. “What’s going on?” Mr. Abbott asked him. The choreographer looked at Mr. Abbott, shook his head. “I can’t figure out what they should do next.” Mr. Abbott never stopped moving. He jumped the three feet from the stage into the aisle. “Well, have them do something!” Mr. Abbott said. “That way we’ll have something to change.”

This is a classic piece of advice, and the fact that it comes up during a discussion of the writing of Absolute Power doesn’t diminish its importance. Shortly afterward, Goldman adds: “Stephen Sondheim once said this: ‘I cannot write a bad song. You begin it here, build, end there. The words will lay properly on the music so they can be sung, that kind of thing. You may hate it, but it will be a proper song.’ I sometimes feel that way about my screenplays. I’ve been doing them for so long now, and I’ve attempted most genres. I know about entering the story as late as possible, entering each scene as late as possible, that kind of thing. You may hate it, but it will be a proper screenplay.” And he writes of his initial stab at Absolute Power: “This first draft was proper as hell—you just didn’t give a shit.”

I think about that last line a lot, with its implication that even prodigious levels of craft and experience won’t necessarily lead to anything worthwhile. (Walter Murch gets at something similar when he notes that the best we can hope to achieve in life is a B, and the rest is up to the gods.) And it’s his awareness that success is largely out of our hands, along with his willingness to discuss his failures along with his triumphs, that results in Goldman’s remarkable air of authority. His books are full of great insights into screenwriting, but there are plenty of other valuable works available on the subject, and if you’re just looking for a foolproof system for constructing scripts, David Mamet’s On Directing Film probably offers more useful information in a fifth of the space. Other screenwriters, including Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne in Monster, have spoken just as openly about the frustrations of working in Hollywood. Goldman’s gift was his ability to somehow do both at the same time, while enhancing both sides in the process. My favorite example is the chapter in Adventures in the Screen Trade devoted to All the President’s Men. Goldman tells us a lot about structure and process, including his decision to end the movie halfway through the original book: “Bernstein and Woodward had made one crucial mistake dealing with the knowledge of one of Nixon’s top aides. It was a goof that, for a while, cost them momentum. I decided to end the story on their mistake, because the public already knew they had eventually been vindicated, and one mistake didn’t stop them. The notion behind it was to go out with them down and let the audience supply their eventual triumph.” He shares a few juicy anecdotes about Carl Bernstein and Nora Ephron, and he discusses his eventual disillusionment with the whole project. And he finally tells us that if he could live his entire movie career over again, “I’d have written exactly the screenplays I’ve written. Only I wouldn’t have come near All the President’s Men.”

What Goldman doesn’t mention is the minor point that the screenplay also won him his second Oscar. In fact, he uses exactly the same strategy in his discussion of All the President’s Men that he did in the movie itself—he ends it on a down note, and he lets us supply his eventual triumph. And I think that this gets at something important about Goldman’s sly appeal. Few other writers have ever managed to pull off the conversational tone that he captures in these books, which is vastly more difficult than it seems. (That voice is a big part of the reason why it’s such a joy to read his thoughts on movies that we’ve never seen, and I deeply regret the nonexistence of an impossible third volume that would tell the stories behind The General’s Daughter, Hearts in Atlantis, and Dreamcatcher.) But it’s also a character that he creates for himself, just as he does in the “autobiographical” sections of The Princess Bride, which draw attention to the artifice that Adventures in the Screen Trade expertly conceals. Goldman mostly comes off as likable as possible, which can only leave out many of the true complexities of a man who spent years as the most successful and famous screenwriter in the world. In Which Lie Did I Tell?, Goldman recounts a story that seems startlingly unlike his usual persona, about his miserable experience working on Memoirs of an Invisible Man:

The…memory is something I think I said. (I read in a magazine that I did, although I have no real recollection of it.) Chevy [Chase] and [producer Bruce] Bodner tried to bring me back after the fiasco. For one final whack at the material…They were both gentlemen and I listened. Then I got up, said this: “I’m sorry, but I’m too old and too rich to put up with this shit.”

He concludes: “Wouldn’t that be neat if it was me?” And the side of him that it reveals, even briefly, suggests that a real biography of Goldman would be a major event. In his account of the writing of The Ghost and the Darkness, he warns against the dangers of backstory, or spelling out too much about the protagonist’s past, and he ends by admonishing us: “Hollywood heroes must have mystery.” And so did William Goldman.

Clinging to the iceberg

One of the things always looming is that I have a reputation as a money writer and—this sounds very bullshitty—I’ve never written for money. By which, I don’t mean that I am artistic and pure. What I mean is, money has happened. It’s gone along with what I’ve written—especially in film. And I like to think one of the reasons for that is I’ve wanted to do what I’ve done. I have gotten very few compliments that I treasure in my life, but one of them is from Stanley Donen, a wonderful director who is now out of repute…He said, “You’re very tough.” And I said, “Why?” And he said, “Because you cost a lot, and you have to want to do it.” I think that’s true, and I treasure that, because I do have to want to do it. I think that’s true basically of almost everybody I know in the picture business that’s above the water level on the iceberg. We’re all clinging to the iceberg, and the water level is rising constantly…

The other compliment which I treasure is from a friend of mine. These are the only two. A friend of mine said to me, “Whatever part of you is a writer you really protect.” It seems to me that’s essential, because the minute you start getting involved with reviews, or interviews…or hype on movies, or any kind of extracurricular lecturing or answering fan letters or any kind of stuff like that—it has nothing to do with writing. And you can begin to become Peter Bogdanovich and believe your own press clippings, and then it’s disaster time. It seems to me that it’s essential to maintain a low profile and go about your business as quietly as possible.

—William Goldman, to John Brady in The Craft of the Screenwriter

The soul of a new machine

Over the weekend, I took part in a panel at Windycon titled “Evil Computers: Why Didn’t We Just Pull the Plug?” Naturally, my mind turned to the most famous evil computer in all of fiction, so I’ve been thinking a lot about HAL, which made me all the more sorry to learn yesterday of the death of voice actor Douglas Rain. (Stan Lee also passed away, of course, which is a subject for a later post.) I knew that Rain had been hired to record the part after Stanley Kubrick was dissatisfied by an earlier attempt by Martin Balsam, but I wasn’t aware that the director had a particular model in mind for the elusive quality that he was trying to evoke, as Kate McQuiston reveals in the book We’ll Meet Again:

Would-be HALs included Alistair Cooke and Martin Balsam, who read for the part but was deemed too emotional. Kubrick set assistant Benn Reyes to the task of finding the right actor, and expressly not a narrator, to supply the voice. He wrote, “I would describe the quality as being sincere, intelligent, disarming, the intelligent friend next door, the Winston Hibler/Walt Disney approach. The voice is neither patronizing, nor is it intimidating, nor is it pompous, overly dramatic, or actorish. Despite this, it is interesting. Enough said, see what you can do.” Even Kubrick’s U.S. lawyer, Louis Blau, was among those making suggestions, which included Richard Basehart, José Ferrer, Van Heflin, Walter Pigeon, and Jason Robards. In Douglas Rain, who had experience both as an actor and a narrator, Kubrick found just what he was looking for: “I have found a narrator…I think he’s perfect, he’s got just the right amount of the Winston Hibler, the intelligent friend next door quality, with a great deal of sincerity, and yet, I think, an arresting quality.”

Who was Winston Hibler? He was the producer and narrator for Disney who provided voiceovers for such short nature documentaries as Seal Island, In Beaver Valley, and White Wilderness, and the fact that Kubrick used him as a touchstone is enormously revealing. On one level, the initial characterization of HAL as a reassuring, friendly voice of information has obvious dramatic value, particularly as the situation deteriorates. (It’s the same tactic that led Richard Kiley to figure in both the novel and movie versions of Jurassic Park. And I have to wonder whether Kubrick ever weighed the possibility of hiring Hibler himself, since in other ways, he clearly spared no expense.) But something more sinister is also at play. As I’ve mentioned before, Disney and its aesthetic feels weirdly central to the problem of modernity, with its collision between the sentimental and the calculated, and the way in which its manufactured feeling can lead to real memories and emotion. Kubrick, a famously meticulous director who looked everywhere for insights into craft, seems to have understood this. And I can’t resist pointing out that Hibler did the voiceover for White Wilderness, which was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Documentary Short, but also included a scene in which the filmmakers deliberately herded lemmings off a cliff into the water in a staged mass suicide. As Hibler smoothly narrates in the original version: “A kind of compulsion seizes each tiny rodent and, carried along by an unreasoning hysteria, each falls into step for a march that will take them to a strange destiny. That destiny is to jump into the ocean. They’ve become victims of an obsession—a one-track thought: ‘Move on! Move on!’ This is the last chance to turn back, yet over they go, casting themselves out bodily into space.”

And I think that Kubrick’s fixation on Hibler’s voice, along with the version later embodied by Rain, gets at something important about our feelings toward computers and their role in our lives. In 2001, the astronauts are placed in an artificial environment in which their survival depends on the outwardly benevolent HAL, and one of the central themes of science fiction is what happens when this situation expands to encompass an entire civilization. It’s there at the very beginning of the genre’s modern era, in John W. Campbell’s “Twilight,” which depicts a world seven million years in the future in which “perfect machines” provide for our every need, robbing the human race of all initiative. (Campbell would explore this idea further in “The Machine,” and he even offered an early version of the singularity—in which robots learn to build better versions of themselves—in “The Last Evolution.”) Years later, Campbell and Asimov put that relationship at the heart of the Three Laws of Robotics, the first of which states: “A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.” This sounds straightforward enough, but as writers realized almost right away, it hinges on the definition of certain terms, including “human being” and “harm,” that are slipperier than they might seem. Its ultimate expression was Jack Williamson’s story “With Folded Hands,” which carried the First Law to its terrifying conclusion. His superior robots believe that their Prime Directive is to prevent all forms of unhappiness, which prompts them to drug or lobotomize any human beings who seem less than content. As Williamson said much later in an interview with Larry McCaffery: “The notion I was consciously working on specifically came out of a fragment of a story I had worked on for a while about an astronaut in space who is accompanied by a robot obviously superior to him physically…Just looking at the fragment gave me the sense of how inferior humanity is in many ways to mechanical creations.”

Which brings us back to the singularity. Its central assumption was vividly expressed by the mathematician I.J. Good, who also served as a consultant on 2001:

Let an ultraintelligent machine be defined as a machine that can far surpass all the intellectual activities of any man however clever. Since the design of machines is one of these intellectual activities, an ultraintelligent machine could design even better machines; there would then unquestionably be an ‘intelligence explosion,’ and the intelligence of man would be left far behind. Thus the first ultraintelligent machine is the last invention that man need ever make, provided that the machine is docile enough to tell us how to keep it under control.

That last clause is a killer, but even if we accept that such a machine would be “docile,” it also embodies the fear, which Campbell was already exploring in the early thirties, of a benevolent dictatorship of machines. And the very Campbellian notion of “the last invention” should be frightening in itself. The prospect of immortality may be enticing, but not if it emerges through a technological singularity that leaves us unprepared to deal with the social consequences, rather than through incremental scientific and medical progress—and the public debate that it ought to inspire—that human beings have earned for themselves. I can’t imagine anything more nightmarish than a world in which we can all live forever without having gone through the necessary ethical, political, and ecological stages to make such a situation sustainable. (When I contemplate living through the equivalent of the last two years over the course of millennia, the notion of eternal life becomes considerably less attractive.) Our fear of computers taking over our lives, whether on a spacecraft or in society as a whole, is really about the surrender of control, even in the benevolent form embodied by Disney. And when I think of the singularity now, I seem to hear it speaking with Winston Hibler’s voice: “Move on! Move on!”

The Other Side of Welles

“The craft of getting pictures made can be so brutal and devious that there is constant need of romancing, liquor, and encouraging anecdotes,” the film critic David Thomson writes in his biography Rosebud, which is still my favorite book about Orson Welles. He’s referring, of course, to a notoriously troubled production that unfolded over the course of many years, multiple continents, and constant threats of financial collapse, held together only by the director’s vision, sheer force of will, and unfailing line of bullshit. It was called Chimes at Midnight. As Thomson says of Welles’s adaptation of the Falstaff story, which was released in 1965:

Prodigies of subterfuge and barefaced cheek were required to get the film made: the rolling plains of central Spain with mountains in the distance were somehow meant to be the wooded English countryside. Some actors were available for only a few days…so their scenes had to be done very quickly and sometimes without time to include the actors they were playing with. So [John] Gielgud did his speeches looking at a stand-in whose shoulder was all the camera saw. He had to do cutaway closeups, with timing and expression dictated by Welles. He felt at a loss, with only his magnificent technique, his trust of the language, and his fearful certainty that Welles was not to be negotiated with carrying him through.

The result, as Thomson notes, was often uneven, with “a series of spectacular shots or movie events [that] seem isolated, even edited at random.” But he closes his discussion of the movie’s troubled history with a ringing declaration that I often repeat to myself: “No matter the dreadful sound, the inappropriateness of Spanish landscapes, no matter the untidiness that wants to masquerade as poetry, still it was done.”

Those last three words have been echoing in my head ever since I saw The Other Side of the Wind, Welles’s legendary unfinished last film, which was finally edited together and released last weekend on Netflix. I’m frankly not ready yet to write anything like a review, except to say that I expect to watch it again on an annual basis for the rest of my life. And it’s essential viewing, not just for film buffs or Welles fans, but for anyone who wants to make art of any kind. Even more than Chimes at Midnight, it was willed into existence, and pairing an attentive viewing with a reading of Josh Karp’s useful book Orson Welles’s Last Movie amounts to a crash course in making movies, or just about anything else, under the the most unforgiving of circumstances. The legend goes that Citizen Kane has inspired more directorial careers than any other film, but it was also made under conditions that would never be granted to any novice director ever again. The Other Side of the Wind is a movie made by a man with nothing left except for a few good friends, occasional infusions of cash, boundless ingenuity and experience, and the soul of a con artist. (As Peter Bogdanovich reminds us in his opening narration, he didn’t even have a cell phone camera, which should make us even more ashamed about not following his example.) And you can’t watch it without permanently changing your sense of what it means to make a movie. A decade earlier, Welles had done much the same for Falstaff, as Thomson notes:

The great battle sequence, shot in one of Madrid’s parks, had its big shots with lines of horses. But then, day after day, Welles went back to the park with just a few men, some weapons, and water to make mud to obtain the terrible scenes of close slaughter that make the sequence so powerful and such a feat of montage.

That’s how The Other Side of the Wind seems to have been made—with a few men and some weapons, day after day, in the mud. And it’s going to inspire a lot of careers.

In fact, it’s temping for me to turn this post into a catalog of guerrilla filmmaking tactics, because The Other Side of the Wind is above all else an education in practical strategies for survival. Some of it is clearly visible onscreen, like the mockumentary conceit that allows scenes to be assembled out of whatever cameras or film stocks Welles happened to have available, with footage seemingly caught on the fly. (Although this might be an illusion in itself. According to Karp’s book, which is where most of this information can be found, Welles stationed a special assistant next to the cinematographer to shut off the camera as soon as he yelled “Cut,” so that not even an inch of film would be wasted.) But there’s a lot that you need to look closely to see, and the implications are intoxicating. Most of the movie was filmed on the cheapest available sets or locations—in whatever house Welles happened to be occupying at the time, on an unused studio backlot, or in a car using “poor man’s process,” with crew members gently rocking the vehicle from outside and shining moving lights through the windows. Effects were created with forced perspective, including one in which a black tabletop covered in rocks became an expanse of volcanic desert. As with Chimes of Midnight, a closeup in an interior scene might cut to another that was taken years earlier on another continent. One sequence took so long to film that Oja Kodar, Welles’s girlfriend and creative partner, visibly ages five years from one shot to another. For another scene, Welles asked Gary Graver, his cameraman, to lie on the floor with his camera so that other crew members could drag him around, a “poor man’s dolly” that he claimed to have learned from Jean Renoir. The production went on for years before casting its lead actor, and when John Huston arrived on set, Welles encouraged him to drink throughout the day, both for the sake of characterization and as a way to get the performance that he needed. As Karp writes, the shoot was “a series of strange adventures.”

This makes it even more difficult than usual to separate this movie from the myth of its making, which nobody should want to do in the first place. More than any other film that I can remember, The Other Side of the Wind is explicitly about its own unlikely creation, which was obvious to most of the participants even at the time. This extends even to the casting of Peter Bogdanovich, who plays a character so manifestly based on himself—and on his uneasy relationship to Welles—that it’s startling to learn that he was a replacement at the last minute for Rich Little, who shot hours of footage in the role before disappearing. (As Frank Marshall, who worked on the production, later recalled: “When Peter came in to play Peter, it was bizarre. I always wondered whether Peter knew.”) As good as John Huston is, if the movie is missing anything, it’s Welles’s face and voice, although he was probably wise to keep himself offscreen. But I doubt that anyone will ever mistake this movie for anything but a profoundly personal statement. As Karp writes:

Creating a narrative that kept changing along with his life, and the making of his own film, at some point Welles stopped inventing his story and began recording impressions of his world as it evolved around him. The result was a film that could never be finished. Because to finish it might have meant the end of Orson’s own artistic story—and that was impossible to accept. So he kept it going and going.

This seems about right, except that the story isn’t just about Welles, but about everyone who cared for him or what he represented. It was the testament of a man who couldn’t see tomorrow, but who imposed himself so inescapably on the present that it leaves the rest of us without any excuses. And in a strange quirk of fate, after all these decades, it seems to have appeared at the very moment that we need it the most. At the end of Rosebud, Thomson asks, remarkably, whether Welles had wasted his life on film. He answers his own question at once, in the very last line of the book, and I repeat these words to myself almost every day: “One has to do something.”

The Men Who Saw Tomorrow, Part 3

By now, it might seem obvious that the best way to approach Nostradamus is to see it as a kind of game, as Anthony Boucher describes it in the June 1942 issue of Unknown Worlds: “A fascinating game, to be sure, with a one-in-a-million chance of hitting an astounding bullseye. But still a game, and a game that has to be played according to the rules. And those rules are, above all things else, even above historical knowledge and ingenuity of interpretation, accuracy and impartiality.” Boucher’s work inspired several spirited rebukes in print from L. Sprague de Camp, who granted the rules of the game but disagreed about its harmlessness. In a book review signed “J. Wellington Wells”—and please do keep an eye on that last name—de Camp noted that Nostradamus was “conjured out of his grave” whenever there was a war:

And wonder of wonders, it always transpires that a considerable portion of his several fat volumes of prophetic quatrains refer to the particular war—out of the twenty-odd major conflicts that have occurred since Dr. Nostradamus’s time—or other disturbance now taking place; and moreover that they prophesy inevitable victory for our side—whichever that happens to be. A wonderful man, Nostradamus.

Their affectionate battle culminated in a nonsense limerick that de Camp published in the December 1942 version of Esquire, claiming that if it was still in print after four hundred years, it would have been proven just as true as any of Nostradamus’s prophecies. Boucher responded in Astounding with the short story “Pelagic Spark,” an early piece of fanfic in which de Camp’s great-grandson uses the “prophecy” to inspire a rebellion in the far future against the sinister Hitler XVI.

This is all just good fun, but not everyone sees it as a game, and Nostradamus—like other forms of vaguely apocalyptic prophecy—tends to return at exactly the point when such impulses become the most dangerous. This was the core of de Camp’s objection, and Boucher himself issued a similar warning:

At this point there enters a sinister economic factor. Books will be published only when there is popular demand for them. The ideal attempt to interpret the as yet unfulfilled quatrains of Nostradamus would be made in an ivory tower when all the world was at peace. But books on Nostradamus sell only in times of terrible crisis, when the public wants no quiet and reasoned analysis, but an impassioned assurance that We are going to lick the blazes out of Them because look, it says so right here. And in times of terrible crisis, rules are apt to get lost.

Boucher observes that one of the best books on the subject, Charles A. Ward’s Oracles of Nostradamus, was reissued with a dust jacket emblazoned with such questions as “Will America Enter the War?” and “Will the British Fleet Be Destroyed?” You still see this sort of thing today, and it isn’t just the books that benefit. In 1981, the producer David L. Wolper released a documentary on the prophecies of Nostradamus, The Man Who Saw Tomorrow, that saw subsequent spikes in interest during the Gulf War—a revised version for television was hosted by Charlton Heston—and after the September 11 attacks, when there was a run on the cassette at Blockbuster. And the attention that it periodically inspires reflects the same emotional factors that led to psychohistory, as the host of the original version said to the audience: “Do we really want to know about the future? Maybe so—if we can change it.”

The speaker, of course, was Orson Welles. I had always known that The Man Who Saw Tomorrow was narrated by Welles, but it wasn’t until I watched it recently that I realized that he hosted it onscreen as well, in one of my favorite incarnations of any human being—bearded, gigantic, cigar in hand, vaguely contemptuous of his surroundings and collaborators, but still willing to infuse the proceedings with something of the velvet and gold braid. Keith Phipps of The A.V. Club once described the documentary as “a brain-damaged sequel” to Welles’s lovely F for Fake, which is very generous. The entire project is manifestly ridiculous and exploitative, with uncut footage from the Zapruder film mingling with a xenophobic fantasy of a war of the West against Islam. Yet there are also moments that are oddly transporting, as when Welles turns to the camera and says:

Before continuing, let me warn you now that the predictions of the future are not at all comforting. I might also add that these predictions of the past, these warnings of the future are not the opinions of the producers of the film. They’re certainly not my opinions. They’re interpretations of the quatrains as made by scores of independent scholars of Nostradamus’ work.

In the sly reading of “my opinions,” you can still hear a trace of Harry Lime, or even of Gregory Arkadin, who invited his guests to drink to the story of the scorpion and the frog. And the entire movie is full of strange echoes of Welles’s career. Footage is repurposed from Waterloo, in which he played Louis XVIII, and it glances at the fall of the Shah of Iran, whose brother-in-law funded Welles’s The Other Side of the Wind, which was impounded by the revolutionary government that Nostradamus allegedly foresaw.

Welles later expressed contempt for the whole affair, allegedly telling Merv Griffin that you could get equally useful prophecies by reading at random out of the phone book. Yet it’s worth remembering, as the critic David Thomson notes, that Welles turned all of his talk show interlocutors into versions of the reporter from Citizen Kane, or even into the Hal to his Falstaff, and it’s never clear where the game ended. His presence infuses The Man Who Saw Tomorrow with an unearned loveliness, despite the its many awful aspects, such as the presence of the “psychic” Jeane Dixon. (Dixon’s fame rested on her alleged prediction of the Kennedy assassination, based on a statement—made in Parade magazine in 1960—that the winner of the upcoming presidential election would be “assassinated or die in office though not necessarily in his first term.” Oddly enough, no one seems to remember an equally impressive prediction by the astrologer Joseph F. Goodavage, who wrote in Analog in September 1962: “It is coincidental that each American president in office at the time of these conjunctions [of Jupiter and Saturn in an earth sign] either died or was assassinated before leaving the presidency…John F. Kennedy was elected in 1960 at the time of a Jupiter and Saturn conjunction in Capricorn.”) And it’s hard for me to watch this movie without falling into reveries about Welles, who was like John W. Campbell in so many other ways. Welles may have been the most intriguing cultural figure of the twentieth century, but he never seemed to know what would come next, and his later career was one long improvisation. It might not be too much to hear a certain wistfulness when he speaks of the man who could see tomorrow, much as Campbell’s fascination with psychohistory stood in stark contrast to the confusion of the second half of his life. When The Man Who Saw Tomorrow was released, Welles had finished editing about forty minutes of his unfinished masterpiece The Other Side of the Wind, and for decades after his death, it seemed that it would never be seen. Instead, it’s available today on Netflix. And I don’t think that anybody could have seen that coming.

Fire and Fury

I’ve been thinking a lot recently about Brian De Palma’s horror movie The Fury, which celebrated its fortieth anniversary earlier this year. More specifically, I’ve been thinking about Pauline Kael’s review, which is one of the pieces included in her enormous collection For Keeps. I’ve read that book endlessly for two decades now, and as a result, The Fury is one of those films from the late seventies—like Philip Kaufman’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers—that endure in my memory mostly as a few paragraphs of Kael’s prose. In particular, I often find myself remembering these lines:

De Palma is the reverse side of the coin from Spielberg. Close Encounters gives us the comedy of hope. The Fury is the comedy of cruelly dashed hope. With Spielberg, what happens is so much better than you dared hope that you have to laugh; with De Palma, it’s so much worse than you feared that you have to laugh.

That sums up how I feel about a lot of things these days, when everything is consistently worse than I could have imagined, although laughter usually feels very far away. (Another line from Kael inadvertently points to the danger of identifying ourselves with our political heroes: “De Palma builds up our identification with the very characters who will be destroyed, or become destroyers, and some people identified so strongly with Carrie that they couldn’t laugh—they felt hurt and betrayed.”) And her description of one pivotal scene, which appears in her review of Dressed to Kill, gets closer than just about anything else to my memories of the last presidential election: “There’s nothing here to match the floating, poetic horror of the slowed-down sequence in which Amy Irving and Carrie Snodgress are running to freedom: it’s as if each of them and each of the other people on the street were in a different time frame, and Carrie Snodgress’s face is full of happiness just as she’s flung over the hood of a car.”

The Fury seems to have been largely forgotten by mainstream audiences, but references to it pop up in works ranging from Looper to Stranger Things, and I suspect that it might be due for a reappraisal. It’s about two teenagers, a boy and a girl, who have never met, but who share a psychic connection. As Kael notes, they’re “superior beings” who might have been prophets or healers in an earlier age, but now they’ve been targeted by our “corrupt government…which seeks to use them for espionage, as secret weapons.” Reading this now, I’m slightly reminded of our current administration’s unapologetic willingness to use vulnerable families and children as political pawns, but that isn’t really the point. What interests me more is how De Palma’s love of violent imagery undercuts the whole moral arc of the movie. I might call this a problem, except that it isn’t—it’s a recurrent feature of his work that resonated uneasily with viewers who were struggling to integrate the specter of institutionalized violence into their everyday lives. (In a later essay, Kael wrote of acquaintances who resisted such movies because of its association with the “guilty mess” of the recently concluded war: “There’s a righteousness in their tone when they say they don’t like violence; I get the feeling that I’m being told that my urging them to see The Fury means that I’ll be responsible if there’s another Vietnam.”) And it’s especially striking in this movie, which for much of its length is supposedly about an attempt to escape this cycle of vengeance. Of the two psychic teens, Robyn, played by Andrew Stevens, eventually succumbs to it, while Gillian, played by Amy Irving, fights it for as long as she can. As Kael explains: “Both Gillian and Robyn have the power to zap people with their minds. Gillian is trying to cling to her sanity—she doesn’t want to hurt anyone. And, knowing that her power is out of her conscious control, she’s terrified of her own secret rages.”

And it’s hard for me to read this passage now without connecting it to the ongoing discussion over women’s anger, in which the word “fury” occurs with surprising frequency. Here’s the journalist Rebecca Traister writing in the New York Times, in an essay adapted from her bestselling book Good and Mad:

Fury was a tool to be marshaled by men like Judge Kavanaugh and Senator Graham, in defense of their own claims to political, legal, public power. Fury was a weapon that had not been made available to the woman who had reason to question those claims…Most of the time, female anger is discouraged, repressed, ignored, swallowed. Or transformed into something more palatable, and less recognizable as fury—something like tears. When women are truly livid, they often weep…This political moment has provoked a period in which more and more women have been in no mood to dress their fury up as anything other than raw and burning rage.

Traister’s article was headlined: “Fury is a Political Weapon. And Women Need to Wield It.” And if you were so inclined, you could take The Fury as an extended metaphor for the issue that Casey Cep raises in her recent roundup of books on the subject in The New Yorker: “A major problem with anger is that some people are allowed to express it while others are not.” In the film, Gillian spends most of the movie resisting her violent urges, while her male psychic twin gives into them, and the climax—which is the only scene that most viewers remember—hinges on her embrace of the rage that Robyn passed to her at the moment of his death.

This brings us to Childress, the villain played by John Cassavetes, whose demise Kael hyperbolically describes as “the greatest finish for any villain ever.” A few paragraphs earlier, Kael writes of this scene:

This is where De Palma shows his evil grin, because we are implicated in this murderousness: we want it, just as we wanted to see the bitchy Chris get hers in Carrie. Cassavetes is an ideal villain (as he was in Rosemary’s Baby)—sullenly indifferent to anything but his own interests. He’s so right for Childress that one regrets that there wasn’t a real writer around to match his gloomy, viscous nastiness.

“Gloomy, viscous nastiness” might ring a bell today, and Childress’s death—Gillian literally blows him up with her mind—feels like the embodiment of our impulses for punishment, revenge, and retribution. It’s stunning how quickly the movie discards Gillian’s entire character arc for the sake of this moment, but what makes the ending truly memorable is what happens next, which is nothing. Childress explodes, and the film just ends, because it has nothing left to show us. That works well enough in a movie, but in real life, we have to face the problem of what Brittney Cooper, whose new book explicitly calls rage a superpower, sums up as “what kind of world we want to see, not just what kind of things we want to get rid of.” In her article in The New Yorker, Cep refers to the philosopher and classicist Martha Nussbaum’s treatment of the Furies themselves, who are transformed at the end of the Oresteia into the Eumenides, “beautiful creatures that serve justice rather than pursue cruelty.” It isn’t clear how this transformation takes place, and De Palma, typically, sidesteps it entirely. But if we can’t imagine anything beyond cathartic vengeance, we’re left with an ending closer to what Kael writes of Dressed to Kill: “The spell isn’t broken and [De Palma] doesn’t fully resolve our fear. He’s saying that even after the horror has been explained, it stays with you—the nightmare never ends.”

First man, first communion

On July 5, 1969, eleven days before the launch of Apollo 11, Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins took part in an unusual press conference at the Manned Space Center in Houston. Because they were being kept in quarantine, the astronauts answered questions while seated behind a desk inside a large plastic box. One of the attendees was Norman Mailer, who describes the scene in his book Of a Fire on the Moon, which he narrates under the name Aquarius:

Behind them at the rear of the plastic booth stood an American flag; the Press actually jeered when somebody brought it onstage in advance of the astronauts. Aquarius could not remember a press conference where Old Glory had ever been mocked before, but it had no great significance, suggesting rather a splash of derision at the thought that the show was already sufficiently American enough.

When an international correspondent asked about the decision to plant an American flag on the lunar surface, Armstrong offered a characteristic answer: “Well, I suspect that if we asked all the people in the audience and all of us up here, all of us would give different ideas on what they would like to take to the moon and think should be taken, everyone within his own experience. I don’t think there is any question what our job is. Our job is to fly the spacecraft as best as we can. We never would suggest that it is our responsibility to suggest what the U.S. posture on the moon should be. That decision has been made where it should be made, namely in the Congress of this country. I wouldn’t presume to question it.”

I was reminded of Armstrong’s measured reply in light of the controversy that briefly flared up over Damien Chazelle’s upcoming biopic First Man, which apparently fails to show the moment in which the flag was raised on the moon. This doesn’t mean that it isn’t displayed at all—it seems to be prominently featured in several shots—but the absence of a scene in which the flag is explicitly planted on lunar soil has led to criticism from exactly the sort of people you might suspect. In response, Chazelle has explained: “My goal with this movie was to share with audiences the unseen, unknown aspects of America’s mission to the moon—particularly Neil Armstrong’s personal saga and what he may have been thinking and feeling during those famous few hours.” And it seems clear that Armstrong wasn’t particularly concerned with the flag itself. Decades later, he said to James R. Hansen, the author of the authorized biography on which the film is based:

Some people thought a United Nations flag should be there, and some people thought there should be flags of a lot of nations. In the end, it was decided by Congress that this was a United States project. We were not going to make any territorial claim, but we ought to let people know that we were here and put up a U.S. flag. My job was to get the flag there. I was less concerned about whether that was the right artifact to place. I let other, wiser minds than mine make those kinds of decisions.

This feels like Armstrong’s diplomatic way of saying that he had more pressing concerns, and the planting of the flag seems to have been less important to him in the moment than it would later be, say, to Marco Rubio.

For any event as complicated and symbolically weighted as the first moon landing, we naturally choose which details to emphasize or omit, which was true even at the time. In the book First Man, Hansen recounts a scene in the Lunar Module that wasn’t widely publicized:

Aldrin…reached into his Personal Preference Kit, or PPK, and pulled out two small packages given to him by his Presbyterian minister, Reverend Dean Woodruff, back in Houston. One package contained a vial of wine, the other a wafer. Pouring the wine into a small chalice that he also pulled from his kit, he prepared to take Holy Communion…Buzz radioed, “Houston, this is the LM pilot speaking. I would like to request a few moments of silence. I would like to invite each person listening in, wherever or whoever he may be, to contemplate the events of the last few hours and to give thanks in his own individual way.”

Originally, Aldrin had hoped to read aloud from the Book of John, but NASA—evidently concerned by the threat of legal action from the atheist Madalyn Murray O’Hair—encouraged him to keep the ritual to himself. (Word did leak from the minister to Walter Cronkite, who informed viewers that Aldrin would have “the first communion on the moon.”) And Armstrong’s feelings on the subject were revealing. As Hansen writes:

Characteristically, Neil greeted Buzz’s religious ritual with polite silence. “He had told me he planned a little celebratory communion,” Neil recalls, “and he asked me if I had any problems with that, and I said, ‘No, go right ahead.’ I had plenty of things to keep busy with. I just let him do his own thing.”

The fact that NASA hoped to pass over the moment discreetly only reflects how much selection goes into the narratives of such events—and our sense of what matters can change from one day to the next. In Of a Fire on the Moon, Mailer follows up his account of the jeers at the press conference with a striking anecdote from the landing itself:

When the flag was set up on the moon, the Press applauded. The applause continued, grew larger—soon they would be giving the image of the flag a standing ovation. It was perhaps a way of apologizing for the laughter before, and the laughter they knew would come again, but the experience was still out of register. A reductive society was witnessing the irreducible.

In fact, we reduce all such events sooner or later to a few simple components, which tend to confirm our own beliefs. (Aldrin later had second thoughts about his decision to take communion on the moon, noting that “we had come to space in the name of all mankind—be they Christians, Jews, Muslims, animists, agnostics, or atheists.” Notably, in her lawsuit against NASA, O’Hair had alleged that the agency was covering up the fact that Armstrong was an atheist. Armstrong, who described himself as a “deist,” wasn’t much concerned with the matter, as he later told Hansen: “I can’t say I was very familiar with that. I don’t remember that ever being mentioned to me until sometime in the aftermath of the mission.” And my favorite lunar urban legend is the rumor that Armstrong converted to Islam after hearing the Muslim call to prayer on the moon.) But such readings are a luxury granted only to those whose role is to observe. Throughout his career, Armstrong remained focused on the logistics of the mission, which were more than enough to keep him busy. He was content to leave the interpretation to others. And that’s a big part of the reason why he got there first.

The Rover Boys in the Air

On September 3, 1981, a man who had recently turned seventy reminisced in a letter to a librarian about his favorite childhood books, which he had read in his youth in Dixon, Illinois:

I, of course, read all the books that a boy that age would like—The Rover Boys; Frank Merriwell at Yale; Horatio Alger. I discovered Edgar Rice Burroughs and read all the Tarzan books. I am amazed at how few people I meet today know that Burroughs also provided an introduction to science fiction with John Carter of Mars and the other books that he wrote about John Carter and his frequent trips to the strange kingdoms to be found on the planet Mars.

At almost exactly the same time, a boy in Kansas City was working his way through a similar shelf of titles, as described by one of his biographers: “Like all his friends, he read the Rover Boys series and all the Horatio Alger books…[and] Edgar Rice Burroughs’s wonderful and exotic Mars books.” And a slightly younger member of the same generation would read many of the same novels while growing up in Brooklyn, as he recalled in his memoirs: “Most important of all, at least to me, were The Rover Boys. There were three of them—Dick, Tom, and Sam—with Tom, the middle one, always described as ‘fun-loving.’”

The first youngster in question was Ronald Reagan; the second was Robert A. Heinlein; and the third was Isaac Asimov. There’s no question that all three men grew up reading many of the same adventure stories as their contemporaries, and Reagan’s apparent fondness for science fiction has inspired a fair amount of speculation. In a recent article on Slate, Kevin Bankston retells the famous story of how WarGames inspired the president to ask his advisors about the likelihood of such an incident occurring for real, concluding that it was “just one example of how science fiction influenced his administration and his life.” The Day the Earth Stood Still, which was adapted from a story by Harry Bates that originally appeared in Astounding, allegedly influenced Regan’s interest in the potential effect of extraterrestrial contact on global politics, which he once brought up with Gorbachev. And in the novelistic biography Dutch, Edmund Morris—or his narrative surrogate—ruminates at length on the possible origins of the Strategic Defense Initiative:

Long before that, indeed, [Reagan] could remember the warring empyrean of his favorite boyhood novel, Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Princess of Mars. I keep a copy on my desk: just to flick through it is to encounter five-foot-thick polished glass domes over cities, heaven-filling salvos, impregnable walls of carborundum, forts, and “manufactories” that only one man with a key can enter. The book’s last chapter is particularly imaginative, dominated by the magnificent symbol of a civilization dying for lack of air.

For obvious marketing reasons, I’d love to be able to draw a direct line between science fiction and the Reagan administration. Yet it’s also tempting to read a greater significance into these sorts of connections than they actually deserve. The story of science fiction’s role in the Strategic Defense Initiative has been told countless times, but usually by the writers themselves, and it isn’t clear what impact it truly had. (The definitive book on the subject, Way Out There in the Blue by Frances FitzGerald, doesn’t mention any authors at all by name, and it refers only once, in passing, to a group of advisors that included “a science fiction writer.” And I suspect that the most accurate description of their involvement appears in a speech delivered by Greg Bear: “Science fiction writers helped the rocket scientists elucidate their vision and clarified it.”) Reagan’s interest in science fiction seems less like a fundamental part of his personality than like a single aspect of a vision that was shaped profoundly by the popular culture of his young adulthood. The fact that Reagan, Heinlein, and Asimov devoured many of the same books only tells me that this was what a lot of kids were reading in the twenties and thirties—although perhaps only the exceptionally imaginative would try to live their lives as an extension of those stories. If these influences were genuinely meaningful, we should also be talking about the Rover Boys, a series “for young Americans” about three brothers at boarding school that has now been almost entirely forgotten. And if we’re more inclined to emphasize the science fiction side for Reagan, it’s because this is the only genre that dares to make such grandiose claims for itself.

In fact, the real story here isn’t about science fiction, but about Reagan’s gift for appropriating the language of mainstream culture in general. He was equally happy to quote Dirty Harry or Back to the Future, and he may not even have bothered to distinguish between his sources. In Way Out There in the Blue, FitzGerald brilliantly unpacks a set of unscripted remarks that Reagan made to reporters on March 24, 1983, in which he spoke of the need of rendering nuclear weapons “obsolete”:

There is a part of a line from the movie Torn Curtain about making missiles “obsolete.” What many inferred from the phrase was that Reagan believed what he had once seen in a science fiction movie. But to look at the explanation as a whole is to see that he was following a train of thought—or simply a trail of applause lines—from one reassuring speech to another and then appropriating a dramatic phrase, whose origin he may or may not have remembered, for his peroration.

Take out the world “reassuring,” and we have a frightening approximation of our current president, whose inner life is shaped in real time by what he sees on television. But we might feel differently if those roving imaginations had been channeled by chance along different lines—like a serious engagement with climate change. It might just as well have gone that way, but it didn’t, and we’re still dealing with the consequences. As Greg Bear asks: “Do you want your presidents to be smart? Do you want them to be dreamers? Or do you want them to be lucky?”

Don’t look now

Note: This post discusses elements of the series finale of HBO’s Sharp Objects.

It’s been almost twenty years since I first saw Don’t Look Now at a revival screening at the Brattle Theatre in Cambridge, Massachusetts. I haven’t seen it again, but I’ve never gotten over it, and it remains one of my personal cinematic touchstones. (My novelette “Kawataro,” which is largely an homage to Japanese horror, includes a nod to its most famous visual conceit.) And it’s impossible to convey its power without revealing its ending, which I’m afraid I’ll need to do here. For most of its length, Nicholas Roeg’s movie is an evocative supernatural mystery set in Venice, less about conventional scares than about what the film critic Pauline Kael describes as its “unnerving cold ominousness,” with Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie as a husband and wife mourning the recent drowning death of their daughter. Throughout the movie, Sutherland glimpses a childlike figure in a red raincoat, which his daughter was wearing when she died. Finally, in the film’s closing minutes, he catches up with what he thinks is her ghost, only to find what Kael calls “a hideous joke of nature—their own child become a dwarf monstrosity.” A wrinkled crone in red, who is evidently just a serial killer, slashes him to death, in one of the great shock endings in the history of movies. Kael wasn’t convinced by it, but it clearly affected her as much as it did me:

The final kicker is predictable, and strangely flat, because it hasn’t been made to matter to us; fear is decorative, and there’s nothing to care about in this worldly, artificial movie. Yet at a mystery level the the movie can still affect the viewer; even the silliest ghost stories can. It’s not that I’m not impressionable; I’m just not as proud of it as some people are.