Posts Tagged ‘Buckminster Fuller’

Fuller at the 92Y

I’m very excited to announce that I’ll be giving a two-part online talk on the life and work of Buckminster Fuller in partnership with the 92nd Street Y on May 13 and 20. It’s hosted through Roundtable, their virtual education platform, so anyone can attend. I expect that it will be the most comprehensive talk that I’ll ever give on Fuller—I plan to cover every important episode from my biography Inventor of the Future—and I’m hoping to attract a receptive audience. If you have a chance, I’d appreciate it very much if you could spread the word—and I hope to see some of you there!

Back to the Future

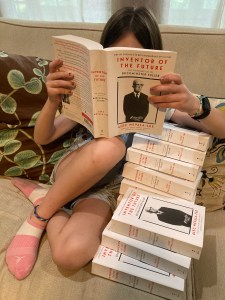

It’s hard to believe, but the paperback edition of Inventor of the Future: The Visionary Life of Buckminster Fuller is finally in stores today. As far as I’m concerned, this is the definitive version of this biography—it incorporates a number of small fixes and revisions—and it marks the culmination of a journey that started more than five years ago. It also feels like a milestone in an eventful writing year that has included a couple of pieces in the New York Times Book Review, an interview with the historian Richard Rhodes on Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer for The Atlantic online, and the usual bits and bobs elsewhere. Most of all, I’ve been busy with my upcoming biography of the Nobel Prize-winning physicist Luis W. Alvarez, which is scheduled to be published by W.W. Norton sometime in 2025. (Oppenheimer fans with sharp eyes and good memories will recall Alvarez as the youthful scientist in Lawrence’s lab, played by Alex Wolff, who shows Oppenheimer the news article announcing that the atom has been split. And believe me, he went on to do a hell of a lot more. I can’t wait to tell you about it.)

Ringing in the new

By any measure, I had a pretty productive year as a writer. My book Inventor of the Future: The Visionary Life of Buckminster Fuller was released after more than three years of work, and the reception so far has been very encouraging—it was named a New York Times Book Review Editors’ Choice, an Economist best book of the year, and, wildest of all, one of Esquire‘s fifty best biographies of all time. (My own vote would go to David Thomson’s Rosebud, his fantastically provocative biography of Orson Welles.) On the nonfiction front, I rounded out the year with pieces in Slate (on the misleading claim that Fuller somehow anticipated the principles of cryptocurrency) and the New York Times (on the remarkable British writer R.C. Sherriff and his wonderful novel The Hopkins Manuscript). Best of all, the latest issue of Analog features my 36,000-word novella “The Elephant Maker,” a revised and updated version of an unpublished novel that I started writing in my twenties. Seeing it in print, along with Inventor of the Future, feels like the end of an era for me, and I’m not sure what the next chapter will bring. But once I know, you’ll hear about it here first.

A Geodesic Life

After three years of work—and more than a few twists and turns—my latest book, Inventor of the Future: The Visionary Life of Buckminster Fuller, is finally here. I think it’s the best thing that I’ve ever done, or at least the one book that I’m proudest to have written. After last week’s writeup in The Economist, a nice review ran this morning in the New York Times, which is a dream come true, and you can check out excerpts today at Fast Company and Slate. (At least one more should be running this weekend in The Daily Beast.) If you want to hear more about it from me, I’m doing a virtual event today sponsored by the Buckminster Fuller Institute, and on Saturday August 13, I’ll be holding a discussion at the Oak Park Public Library with Sarah Holian of the Frank Lloyd Wright Trust, which will be also be available to view online. There’s a lot more to say here, and I expect to keep talking about Fuller for the rest of my life, but for now, I’m just delighted and relieved to see it out in the world at last.

Inventing the future

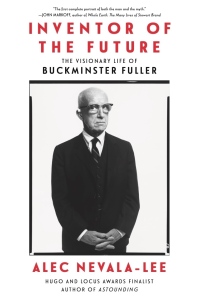

I realize that I’m well overdue for an update on my new book, Inventor of the Future: The Visionary Life of Buckminster Fuller, which is scheduled to be published by Dey Street Books / HarperCollins on August 2. Yesterday, I delivered my revisions to the copy edit, so I’ve essentially reached the end of a process that has lasted three long and challenging years. The result, I think, is the best thing I’ve ever done. It’s a big book—over six hundred pages including the back matter and index—but Fuller more than justifies it, and I hope that it will appeal to both his existing admirers and readers who are encountering him for the first time. (Even if you’re an obsessive Fuller fan, I can guarantee that there’s a lot here that you haven’t seen before.) I’m also delighted by the cover, which features a remarkable portrait of Fuller by Richard Avedon that has rarely been reproduced elsewhere. Obviously, I’ll have a lot more to say about this over the next few months, so check back soon for more!

Allegra Fuller Snyder (1927-2021)

I was saddened to learn that Allegra Fuller Snyder passed away last Sunday at the age of 93. Allegra was a remarkable person in her own right—she was a professor emerita at UCLA and a pioneer in the field of dance ethnology—but I got to know her through the life and work of her father, Buckminster Fuller, whose biography I’ve been writing for the last three years. She navigated the challenges of that unusual legacy with intelligence and compassion, and I owe a great deal to her kindness and support. My thoughts are with her loved ones and friends.

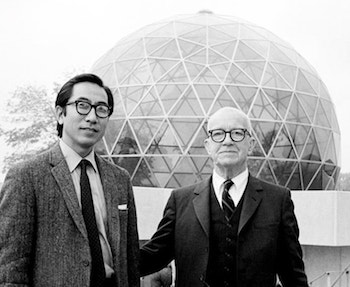

Shoji Sadao (1926-2019)

The architect Shoji Sadao—who worked closely with Buckminster Fuller and the sculptor Isamu Noguchi—passed away earlier this month in Tokyo. I’m briefly quoted in Sadao’s obituary in the New York Times, which draws attention to his largely unsung role in the careers of these two brilliant but demanding men. My contact with Sadao was limited to a few emails and one short phone conversation intended to set up an interview that I’m sorry will never happen, but I’ll be discussing his legacy at length in my upcoming biography of Fuller, and you’ll be hearing a lot more about him here.

A Fuller Life

I’m pleased to announce that I’ve finally figured out the subject of my next book, which will be a biography of the architect and futurist Buckminster Fuller. If you’re a regular reader of this blog, you probably know how much Fuller means to me, and I’m looking forward to giving him the comprehensive portrait that he deserves. (Honestly, that’s putting it mildly. I’ve known for over a week that I’ll have a chance to tackle this project, and I still can’t quite believe that it’s really happening. And I’m especially happy that my current publisher has agreed to give me a shot at it.) At first glance, this might seem like a departure from my previous work, but it presents an opportunity to explore some of the same themes from a different angle, and to explore how they might play out in the real world. The timelines of the two projects largely coincide, with a group of subjects who were affected by the Great Depression, World War II, the Cold War, and the social upheavals of the sixties. All of them had highly personal notions about the fate of America, and Fuller used physical artifacts much as Campbell, Asimov, and Heinlein employed science fiction—to prepare their readers for survival in an era of perpetual change. Fuller’s wife, Anne, played an unsung role in his career that recalls many of the women in Astounding. Like Campbell, he approached psychology as a category of physics, and he hoped to turn the prediction of future trends into a science in itself. His skepticism of governments led him to conclude that society should be changed through design, not political institutions, and like many science fiction writers, he acted as if all disciplines could be reduced to subsets of engineering. And for most of his life, he insisted that complicated social problems could be solved through technology.

Most of his ideas were expressed through the geodesic dome, the iconic work of structural design that made him famous—and I hope that this book will be as much about the dome as about Fuller himself. It became a universal symbol of the space age, and his reputation as a futurist may have been founded largely on the fact that his most recognizable achievement instantly evoked the landscape of science fiction. From the beginning, the dome was both an elegant architectural conceit and a potent metaphor. The concept of a hemispherical shelter that used triangular elements to enclose the maximum amount of space had been explored by others, but Fuller was the first to see it as a vehicle for social change. With design principles that could be scaled up or down without limitation, it could function as a massive commercial pavilion or as a house for hippies. (Ken Kesey dreamed of building a geodesic dome to hold one of his acid tests.) It could be made out of plywood, steel, or cardboard. A dome could be cheaply assembled by hand by amateur builders, which encouraged experimentation, and its specifications could be laid out in a few pages and shared for free, like the modern blueprints for printable houses. It was a hackable, open-source machine for living that reflected a set of tools that spoke to the same men and women who were teaching themselves how to code. As I noted here recently, a teenager named Jaron Lanier, who was living in a tent with his father on an acre of desert in New Mexico, used nothing but the formulas in Lloyd Kahn’s Domebook to design and build a house that he called “Earth Station Lanier.” Lanier, who became renowned years later as the founder of virtual reality, never got over the experience. He recalled decades later: “I loved the place; dreamt about it while sleeping inside it.”

During his lifetime, Fuller was one of the most famous men in America, and he managed to become an idol to both the establishment and the counterculture. In the three decades since his death, his reputation has faded, but his legacy is visible everywhere. The influence of his geodesic structures can be seen in the Houston Astrodome, at Epcot Center, on thousands of playgrounds, in the dome tents favored by backpackers, and in the emergency shelters used after Hurricane Katrina. Fuller had a lasting impact on environmentalism and design, and his interest in unconventional forms of architecture laid the foundation for the alternative housing movement. His homegrown system of geometry led to insights into the biological structure of viruses and the logic of communications networks, and after he died, he was honored by the discoverers of a revolutionary form of carbon that resembled a geodesic sphere, which became known as fullerene, or the buckyball. And I’m particularly intrigued by his parallels to the later generation of startup founders. During the seventies, he was a hero to the likes of Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs, who later featured him prominently in the first “Think Different” commercial, and he was the prototype of the Silicon Valley types who followed. He was a Harvard dropout who had been passed over by the college’s exclusive social clubs, and despite his lack of formal training, he turned himself into an entrepreneur who believed in changing society through innovative products and environmental design. Fuller wore the same outfit to all his public appearances, and his personal habits amounted to an early form of biohacking. (Fuller slept each day for just a few hours, taking a nap whenever he felt tired, and survived mostly on steak and tea.) His closest equivalent today may well be Elon Musk, which tells us a lot about both men.

And this project is personally significant to me. I first encountered Fuller through The Whole Earth Catalog, which opened its first edition with two pages dedicated to his work, preceded by a statement from editor Stewart Brand: “The insights of Buckminster Fuller initiated this catalog.” I was three years old when he died, and I grew up in the shadow of his influence in the Bay Area. The week before my freshman year in high school, I bought a used copy of his book Critical Path, and I tried unsuccessfully to plow through Synergetics. (At the time, this all felt kind of normal, and it’s only when I look back that it seems strange—which tells you a lot about me, too.) Above all else, I was drawn to his reputation as the ultimate generalist, which reflected my idea of what my life should be, and I’m hugely excited by the prospect of returning to him now. Fuller has been the subject of countless other works, but never a truly authoritative biography, which is a project that meets both Susan Sontag’s admonition that a writer should try to be useful and the test that I stole from Lin-Manuel Miranda: “What’s the thing that’s not in the world that should be in the world?” Best of all, the process looks to be tremendously interesting for its own sake—I think it’s going to rewire my brain. It also requires an unbelievable amount of research. To apply the same balanced, fully sourced, narrative approach to his life that I tried to take for Campbell, I’ll need to work through all of Fuller’s published work, a mountain of primary sources, and what might literally be the largest single archive for any private individual in history. I know from experience that I can’t do it alone, and I’m looking forward to seeking help from the same kind of brain trust that I was lucky to have for Astounding. Those of you who have stuck with this blog should be prepared to hear a lot more about Fuller over the next three years, but I wouldn’t be doing this at all if I didn’t think that you might find it interesting. And who knows? He might change your life, too.

The ethereal phase

Like many readers, I first encountered the concept of the singularity—the idea that artificial intelligence will eventually lead to an era of exponential technological change—through the work of the futurist Ray Kurzweil. Fifteen years ago, I was browsing in a bookstore when I came across a copy of his book The Singularity is Near, which I bought on the spot. Kurzweil’s thesis is a powerful one, and, to a point, it remains completely convincing:

What, then, is the Singularity? It’s a future period during which the pace of technological change will be so rapid, its impact so deep, that human life will be irreversibly transformed…The key idea underlying the impending Singularity is that the pace of change of our human-created technology is accelerating and its powers are expanding at an exponential pace. Exponential growth is deceptive. It starts out almost imperceptibly and then explodes with unexpected fury—unexpected, that is, if one does not take care to follow its trajectory.

Kurzweil seems particularly enthusiastic about one purported consequence of this development: “We will gain power over our fates. Our mortality will be in our own hands. We will be able to live as long as we want (a subtly different statement from saying we will live forever).” And he suggests that the turning point will occur “before the middle of this century.”

This line of thinking, which was much more novel back then than it is today, was enough to briefly turn me into a transhumanist, or at least into the approximation of one. But I’m more skeptical now. As I noted here recently, one of Kurzweil’s core arguments—that incremental advances in medical technology will lead to functional immortality to those who can hang around for long enough—was advanced by John W. Campbell as far back as 1949. (Writing in Astounding Science Fiction, Campbell muses that a child will be born one day who never has to do die, and he concludes: “I wonder if that point has been passed? And my own guess is—it has.” There’s no proof yet that he was wrong, but I have my doubts.) And the notion of accelerating change is even older. The historian Henry Adams explores the possibility in an essay published in 1904, and a few years later, in the book Degradation of the Democratic Dogma, he writes of the pace of technological progress:

As each newly appropriated force increased the attraction between the sum of nature’s forces and the volume of human mind, by the usual law of squares, the acceleration hurried society towards the critical point that marked the passage into a new phase as though it were heat impelling water to explode as steam…The curve resembles that of the vaporization of water. The resemblance is too close to be disregarded, for nature loves the logarithm, and perpetually recurs to her inverse square. For convenience, if only as a momentary refuge, the physicist-historian will probably have to try the experiment of taking the law of inverse squares as his standard of social acceleration for the nineteenth century, and consequently for the whole phase, which obliges him to accept it experimentally as a general law of history.

Adams thought that the point of no return would occur around 1917, while Buckminster Fuller, writing over a generation later, speculated that technological change would lead to a post-scarcity society sometime in the late seventies. Such futurists tend to place the pivotal moment at a far enough remove to be plausible, while still potentially within their own lifetimes, which hints at the element of wishful thinking involved. (It’s worth noting that the same amount of time has passed since the publication of The Singularity is Near as elapsed between Adams’s first essay on the subject and the date that he posited for what he liked to call the Ethereal Phase.) And unlike other prophets, they benefit from their ability to frame such speculations in the language of science—and especially of physics and mathematics. Writing from the point of view of a historian, in fact, Adams arrives at something that sounds remarkably like psychohistory:

If values can be given to these attractions, a physical theory of history is a mere matter of physical formula, no more complicated than the formulas of Willard Gibbs or Clerk Maxwell; but the task of framing the formula and assigning the values belongs to the physicist, not to the historian…If the physicist-historian is satisfied with neither of the known laws of mass, astronomical or electric, and cannot arrange his variables in any combination that will conform with a phase-sequence, no resource seems to remain but that of waiting until his physical problems shall be solved, and he shall be able to explain what Force is…Probably the solution of any one of the problems will give the solution for them all.

And each of these men sees exactly what he wants to find in this phenomenon, which amounts to a kind of Rorschach test for futurists. On my bookshelf, I have a book titled The 10% Solution to a Healthy Life, which outlines a health plan based largely on the work of Nathan Pritikin, whose thoughts on diet—and longevity—have turned out to be surprisingly influential. Its author says of his decision to write a book: “Being a scientist and a trained skeptic, I was always turned off by people with strong singular agendas. People out to save my soul or even just my health or well-being were strongly suspect. I felt very uncomfortable, therefore, in this role myself, telling people how they should eat or live.” The author was Ray Kurzweil. He makes no mention of the singularity here, but after another decade, he had moved on to such titles as Fantastic Voyage: Live Long Enough to Live Forever and Transcend: Nine Steps to Living Well Forever. Immortality clearly matters a lot to him, which naturally affects how he views the prospect of accelerating change. By contrast, Adams was most attracted by the possibility of refining the theory of history into a science, as Campbell and Asimov later were, while Fuller saw it as the means to an ecological utopia, which had less to do with environmental awareness than with his desire to free the world’s population to do whatever it wanted with its time. Kurzweil, in turn, sees it as a way for us to live for as long as we want, which is an interest that predated his public association with the singularity, and this is reason enough to be skeptical of everything that he says. Kurzweil is a genius, but he’s also just about the last person we should trust to be objective when it comes to the consequences of accelerating change. I’ll be talking about this more tomorrow.

Under the dome

In the early seventies, a boy named Jaron Lanier was living with his father in a tent near Las Cruces, New Mexico. Decades later, Lanier would achieve worldwide acclaim as one of the founders of virtual reality—his company was the first to sell VR headsets and gloves—but at the time, he was ten years old and recovering from a succession of domestic tragedies. When he was nine, his mother Lilly had been killed in a horrific car accident; he was hospitalized for nearly a year with a series of infections; and his family’s new home burned down the day after construction was completed. Lanier’s father, Ellery, barely managed to scrape together enough money to buy an acre of undeveloped land in the desert, where they lived in tents for two years. (Ellery Lanier was a fascinating figure in his own right, and I hope one day to take a more detailed look at his career. He was a peripheral member of a circle of science fiction writers that included Lester del Rey and the radio host Long John Nebel, and he wrote nonfiction articles in the fifties for Fantastic and Amazing. As a younger man, he had known Gurdjieff and Aldous Huxley, and he was close friends with William Herbert Sheldon, the controversial psychologist best known for coining the terms “ectomorph,” “mesomorph,” and “endomorph,” as well as for his involvement with the Ivy League nude posture photos. Sheldon, in turn, was a numismatist who mentored Walter H. Breen, the husband of Marion Zimmer Bradley, about whom the less said the better. There’s obviously a lot to unpack here, but this post isn’t about that.)

When Lanier was about twelve years old, his father proposed that he design and build a house in which the two of them could live. In his memoir Dawn of the New Everything, Lanier speculates that this was his father’s way of helping him to deal with his recent traumas: “He realized that I needed a meaty obsession if I was ever going to become fully functional again.” At the time, Lanier was fascinated by the work of Hieronymus Bosch, especially The Garden of Earthly Delights, and he was equally intrigued when his father gave him a book titled Plants as Inventors. He decided that they should build a house with elements based on botanical structures, which may have been his father’s plan all along. Lanier remembers:

Ellery said he thought I might enjoy another book, in that case. This turned out to be a roughly designed publication in the form of an extra-thick magazine called Domebook. It was an offshoot of Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth Catalog. Buckminster Fuller had been promoting geodesic domes as ideal structures, and they embodied the techie utopian spirit of the times.

At first, Lanier actually thought that a dome would be too mainstream: “I don’t want our house to be like any other house, and other people are building geodesic domes.” His father replied that it would probably be easier to get a construction permit if they included “this countercultural cliché,” and Lanier ultimately granted the point.

The project lasted for seven years. In the classic Fuller fashion, Lanier began with models made of drinking straws, using the tables from the Domebook to calculate the angles. He recalls:

My design strategy was to mix “conventional” geodesic domes with connecting elements that would be profoundly weird and irregular. There was to be one big dome, about fifty feet across, and a medium-size one, to be connected by a strange passage, which would serve as the kitchen, formed out of two tilted, intersecting nine-sided pyramids…The overall form reminded me a little of the Starship Enterprise—which has two engines connected to a main body and a prominent disc jutting out in front—if you filled out the discs and cylinders of that design into spheres…At any rate it was a form that I liked and that Ellery accepted. There were a few passes back and forth with the building permit people, and ultimately Ellery did have to intervene to argue the case, but we got a permit.

Amazingly enough, it all sort of held together. Like many dome builders, Lanier ran into multiple problems on the construction side, in part because of the unreliable advice of the Domebook, which “pretended to offer solutions when it was actually reporting on ongoing experiments.” A decade later, when Lanier met Stewart Brand for the first time, he volunteered the fact that he had grown up in a dome. Brand asked immediately: “Did it leak?” Lanier replied: “Of course it leaked!”

Yet the really remarkable thing was that it worked at all. Fuller’s architectural ideas may have been flawed in practice, but they became popular in the counterculture for many of the same reasons that later led to the founding of the Homebrew Computer Club. Like a kid learning how to code, with the aid of a few simple formulas, diagrams, and rules of thumb, a teenager could build a house that looked like the Enterprise. It was a hackable approach that encouraged experimentation, and the simplicity of the structural principles involved—you could squeeze them into a couple of pages—allowed the information to be freely distributed, much like today’s online blueprints for printable houses. And Lanier adored the result:

The larger dome was big enough that you could almost focus at infinity while staring up at the curve of the baggy silver ceiling…We called it “the dome,” or “Earth Station Lanier.” One would “go dome” instead of going home…There wasn’t a proper bathroom or kitchen. Instead, tubs, sinks, and showers were inserted into the structure according to how the plumbing could be routed though the bizarre shapes I had chosen. A sink was unusually high off the ground; you needed a stepping stool to use it. Conventional choices regarding privacy, sleep schedules, or studying were not really possible. I loved the place; dreamt about it while sleeping inside it.

His father stayed there for another thirty years. Even after Lanier moved away, he never entirely got over it, and he lives today with his family in a house with an attached structure much like the one he left behind in New Mexico. As he concludes: “We live back in the dome, more or less.”

I’ll be appearing tonight at the Deep Dish reading series at Volumes Bookcafe in Chicago at 7pm, along with Cory Doctorow and an exciting group of speculative fiction writers. Hope to see some of you there!

The beefeaters

Every now and then, I get the urge to write a blog post about Jordan Peterson, the Canadian professor of psychology who has unexpectedly emerged as a superstar pundit in the culture wars and the darling of young conservatives. I haven’t read any of Peterson’s books, and I’m not particularly interested in what I’ve seen of his ideas, so until now, I’ve managed to resist the temptation. What finally broke my resolve was a recent article in The Atlantic by James Hamblin, who describes how Peterson’s daughter Mikhailia has become an unlikely dietary guru by subsisting almost entirely on beef. As Hamblin writes:

[Mikhailia] Peterson described an adolescence that involved multiple debilitating medical diagnoses, beginning with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis…In fifth grade she was diagnosed with depression, and then later something called idiopathic hypersomnia (which translates to English as “sleeping too much, of unclear cause”—which translates further to sorry we really don’t know what’s going on). Everything the doctors tried failed, and she did everything they told her, she recounted to me. She fully bought into the system, taking large doses of strong immune-suppressing drugs like methotrexate…She started cutting out foods from her diet, and feeling better each time…Until, by December 2017, all that was left was “beef and salt and water,” and, she told me, “all my symptoms went into remission.”

As a result of her personal experiences, she began counseling people who were considering a similar diet, a role that she characterizes with what strikes me as an admirable degree of self-awareness: “They mostly want to see that I’m not dead.”

Mikhailia Peterson has also benefited from the public endorsement of her father, who has adopted the same diet, supposedly with positive results. According to Hamblin’s article:

In a July appearance on the comedian Joe Rogan’s podcast, Jordan Peterson explained how Mikhaila’s experience had convinced him to eliminate everything but meat and leafy greens from his diet, and that in the last two months he had gone full meat and eliminated vegetables. Since he changed his diet, his laundry list of maladies has disappeared, he told Rogan. His lifelong depression, anxiety, gastric reflux (and associated snoring), inability to wake up in the mornings, psoriasis, gingivitis, floaters in his right eye, numbness on the sides of his legs, problems with mood regulation—all of it is gone, and he attributes it to the diet…Peterson reiterated several times that he is not giving dietary advice, but said that many attendees of his recent speaking tour have come up to him and said the diet is working for them. The takeaway for listeners is that it worked for Peterson, and so it may work for them.

As Hamblin points out, not everyone agrees with this approach. He quotes Jack Gilbert, a professor of surgery at the University of Chicago: “Physiologically, it would just be an immensely bad idea. A terribly, terribly bad idea.” After rattling off a long list of the potential consequences, including metabolic dysfunction and cardiac problems, Gilbert concludes: “If [Mikhaila] does not die of colon cancer or some other severe cardiometabolic disease, the life—I can’t imagine.”

“There are few accounts of people having tried all-beef diets,” Hamblin writes, and it isn’t clear if he’s aware of one case study that was famous in its time. Buckminster Fuller—the futurist, architect, and designer best known for popularizing the geodesic dome—inspired a level of public devotion at his peak that can only be compared to Peterson’s, or even Elon Musk’s, and he ate little more than beef for the last two decades of his life. Fuller’s reasoning was slightly different, but the motivation and outcome were largely the same, as L. Steven Sieden relates in Buckminster Fuller’s Universe:

[Fuller] suddenly noticed his level of energy decreasing and decided to see if anything could be done about that change…Bucky resolved that since the majority of the energy utilized on earth originated from the sun, he should attempt to acquire the most highly concentrated solar energy available to him as food…He would be most effective if he ate more beef because cattle had eaten the vegetation and transformed the solar energy into a more protein-concentrated food. Hence, he began adhering to a regular diet of beef…His weight dropped back down to 140 pounds, identical to when he was in his early twenties. He also found that his energy level increased dramatically.

Fuller’s preferred cut was the relatively lean London broil, supplemented with salad, fruit, and Jell-O. As his friend Alden Hatch says in Buckminster Fuller: At Home in the Universe: “[London broil] is usually served in thin strips because it is so tough, but Bucky cheerfully chomps great hunks of it with his magnificent teeth.”

Unlike the Petersons, Fuller never seems to have inspired many others to follow his example. In fact, his diet, as Sieden tells it, “caused consternation among many of the holistic, health-oriented individuals to whom he regularly spoke during the balance of his life.” (It may also have troubled those who admired Fuller’s views on sustainability and conservation. As Hamblin notes: “Beef production at the scale required to feed billions of humans even at current levels of consumption is environmentally unsustainable.”) Yet the fact that we’re even talking about the diets of Jordan Peterson and Buckminster Fuller is revealing in itself. Hamblin ties it back to a desire for structure in times of uncertainty, which is precisely what Peterson holds out to his followers:

The allure of a strict code for eating—a way to divide the world into good foods and bad foods, angels and demons—may be especially strong at a time when order feels in short supply. Indeed there is at least some benefit to be had from any and all dietary advice, or rules for life, so long as a person believes in them, and so long as they provide a code that allows a person to feel good for having stuck with it and a cohort of like-minded adherents.

I’ve made a similar argument about diet here before. And Mikhailia Peterson’s example is also tangled up in fascinating ways with the difficulty that many women have in finding treatments for their chronic pain. But it also testifies to the extent to which charismatic public intellectuals like Fuller and Jordan Peterson, who have attained prominence in one particular subject, can insidiously become regarded as authority figures in matters far beyond their true area of expertise. There’s a lot that I admire about Fuller, and I don’t like much about Peterson, but in both cases, we should be just as cautious about taking their word on larger issues as we might when it comes to their diet. It’s more obvious with beef than it is with other aspects of our lives—but it shouldn’t be any easier to swallow.

A choice of categories

A few weeks ago, The Economist published a short article with the intriguing headline “Michel Foucault’s Lessons for Business.” It’s fun to speculate what the corporate world might actually stand to learn from this particular philosopher, who once noted that the capitalist system severely punishes crimes of property while discreetly reserving for itself “the illegality of rights.” In fact, the article is mostly interested in Foucault’s book The Order of Things, in which he examines the unstated assumptions that affect how we divide the universe into categories. The uncredited author begins:

Foucault was obsessed with taxonomies, or how humans split the world into arbitrary mental categories in order “to tame the wild profusion of existing things.” When we flip these around, “we apprehend in one great leap…the exotic charm of another system of thought.” Imagine, for example, a supermarket organized by products’ vintage. Lettuces, haddock, custard and the New York Times would be grouped in an aisle called “items produced yesterday.” Scotch, string, cans of dog food and the discounted Celine Dion DVDs would be in the “made in 2008” aisle.

And the article argues that we should take a closer look at how companies define themselves—how mining firms, for instance, are organized by commodity type, when a geographical analysis would reveal “that their production is often in unstable countries,” and that many of them are inordinately dependent on demand from China.

Speaking of China, Foucault’s interest in such problems had an unexpected inspiration, as he reveals in the preface to The Order of Things:

This book first arose out of a passage in [Jorge Luis] Borges, out of the laughter that shattered, as I read the passage, all the familiar landmarks of my thought—our thought that bears the stamp of our age and our geography—breaking up all the ordered surfaces and all the planes with which we are accustomed to tame the wild profusion of existing things, and continuing long afterwards to disturb and threaten with collapse our age-old distinction between the Same and the Other. This passage quotes a “certain Chinese encyclopedia” in which it is written that “animals are divided into: (a) belonging to the Emperor, (b) embalmed, (c) tame, (d) suckling pigs, (e) sirens, (f) fabulous, (g) stray dogs, (h) included in the present classification, (i) frenzied, (j) innumerable, (k) drawn with a very fine camel-hair brush, (l) et cetera, (m) having just broken the water pitcher, (n) that from a long way off look like flies.” In the wonderment of this taxonomy, the thing we apprehend in one great leap, the thing that, by means of the fable, is demonstrated as the exotic charm of another system of thought, is the limitation of our own, the stark impossibility of thinking that.”

Critics have tried in vain to find the source that Borges was using, if one even existed—although it’s worth noting that Foucault never explicitly affirms that the encyclopedia is real. (Borges attributes it to the German sinologist Franz Kuhn, and it would be a pretty problem for a bright scholar to track down a possible original.)

But you don’t need to resort to fiction to find taxonomies that call all your usual assumptions into question. Recently, while revisiting Buckminster Fuller’s book Critical Path, I was struck by a list of resources that he generated for the World Game, an educational simulation that he devised to encourage ecological thinking:

- Reliably operative and subconsciously sustaining [resources], effectively available twenty-four hours a day, anywhere in the Universe: gravity, love.

- Available only within ten miles of the surface of the Earth in sufficient quantity to conduct sound: i.e., the complex of atmospheric gases whose Sun-induced expansion on the sunny side and shadow-side-of-the-world induced contraction together produce the world’s winds, which in turn produce all the world’s waves.

- Available in sufficient quantity to sustain human life only within two miles above planet Earth’s spherical surface: oxygen.

- Available aboard our planet only during day: sunlight.

- Not everywhere or everywhere available: water, food, clothing, shelter, vision, initiative, friendliness.

- Only partially available for individual human consumption, being also required for industrial production: e.g., water.

- Not publicly available because used entirely by industry, e.g., helium.

- Not available to industry because used entirely by scientific laboratories: e.g., moon rocks.

You can chalk some of this up to Fuller’s simple weirdness, which is inseparable from his genius, but there’s also something undeniably useful about classifying resources by availability, which isn’t far removed from the hypothetical grocery store proposed by The Economist. It’s also revealing that so many of these schemes center on problems of resource allocation, since the categories that we use in practice often amount to a way of tracking the distribution of some finite benefit, material or otherwise. Our cultural debates, in particular, frequently depend on how we position ourselves within the patterns of give and take between groups. (The question of whether someone like Bruno Mars can be guilty of cultural appropriation is either mildly irritating or curiously profound, depending on how you look at it.) And while the classifications of Fuller or Borges’s apocryphal encyclopedist can seem amusingly random, they’re no less arbitrary than others that have evolved over time for practical reasons. If you were designing a political platform from scratch, it might seem absurd to lump together gun rights, opposition to abortion, support of the death penalty, a hard line on immigration, tax cuts, and climate change skepticism, or—in the case of both parties—to want the government to keep out of certain private matters while involving itself deeply in others. These methods of slicing up the world exist to hold together unstable coalitions, or to serve powerful interest groups, and we’ve seen how fragile certain convictions, such as a belief in free markets, can really be. Much of the trauma of this political moment has arisen from the splintering of established categories, or a sudden clarification of which parts truly mattered. The process is bound to continue until we arrive at a point of temporarily stability, which will inevitably find itself shaken apart in the next convulsion. As Borges concludes: “There is no classification of the universe that is not arbitrary and speculative. The reason is quite simple: we do not know what the universe is.”

The switch point

“I’ll tell you a thing that will shock you,” Anthony Burgess once said in an interview with Writers Digest in the late seventies. “It will certainly shock the readers of Writer’s Digest.” Here it is:

What I often do nowadays when I have to, say, describe a room, is to take a page of a dictionary, any page at all, and see if with the words suggested by that one page in the dictionary I can build up a room, build up a scene. This is the kind of puzzle that interests me, keeps me going, and it will even suggest how to describe a girl’s hair, at least some of it will come, but I must keep to that page.

Burgess went on to reveal that a description of a hotel vestibule in his novel M/F was based on a page in W.J. Wilkinson’s Malay English Dictionary, although nobody seemed to have noticed this. He concluded:

The thing you see, it suggests what pictures are on the wall, what color somebody’s wearing, and as most things in life are arbitrary anyway, you’re not doing anything naughty, you’re really normally doing what nature does, you’re just making an entity out of the elements. I do recommend it to young writers.

I love this little trick for two reasons. One is that it’s a convenient way to conduct a raid on the random using nothing but the materials on your desk, which is exactly where you’re most likely to need it. The other is that it only works with the dictionary, rather than with a novel or work of nonfiction. As soon as you’re looking at words that have been chosen by another writer, you inevitably get tangled up with an exterior consciousness. With the dictionary, the only meaning there is the one you extract from it, and it helps that we’re dealing with two levels of impersonal structure—alphabetical order and the slice created by the boundaries of the page. I’m reminded of my favorite description of Buckminster Fuller going over his page proofs:

Galleys galvanize Fuller partly because of the large visual component of his imagination. The effect is reflexive: his imagination is triggered by what the eye frames in front of him. It was the same with manuscript pages: he never liked to turn them over or continue to another sheet. Page = unit of thought. So his mind was retriggered with every galley and its quite arbitrary increment of thought from the composing process.

The key phrase here is “quite arbitrary.” As Burgess puts it: “I must keep to that page.” Total freedom can lead to total paralysis, and simply limiting your options is a form of liberation.

That’s true of nearly every creative strategy, of course, but there’s a deeper point to be made here about the movement from order to disorder to order again. The most useful sources of randomness tend to be works that are rigorously organized. A dictionary is an obvious example, but an even greater one is the I Ching, which is so conceptually perfect that it may actually have retarded the development of Chinese civilization. As the historian Joseph Needham wrote:

The elaborated symbolic system of the Book of Changes was almost from the start a mischievous handicap. It tempted those who were interested in Nature to rest in explanations which were no explanations at all. The Book of Changes was a system for pigeon-holing novelty and then doing nothing more about it. Its universal system of symbolism constituted a stupendous filing-system…The Book of Changes might almost be said to have constituted an organization for “routing ideas through the right channels to the right departments.”

Yet if the I Ching was limiting when taken as a system of thought, that’s also why it made such a good oracle. You don’t get useful results by looking for randomness in chaos, but by taking an existing order, extracting an arbitrary piece of it, and then using it to create something orderly on the other side. It’s the series of switch points that matters. Going from structure to randomness to structure again is more productive than pursuing either extreme on its own, because it’s in those moments of transition that the mind awakens to itself.

Economists speak of the negative impact of “switching costs,” but in creative thinking, it’s usually the act of switching—along with the act of combination—that generates ideas. Not surprisingly, most artists find that they’ve built switch points into their process, even if it isn’t entirely conscious. If you switch too often, you never settle into a groove, but if you don’t switch at all, you end up in a rut. And that rhythm of alternation, as well as the state of mind that it creates, may matter more in the long run than any particular method you use. It has affinities with the concept of dialectic, in which thinking is structured as the movement from thesis to antithesis to a synthesis of the two, and it gets results because of the regular switch points that it demands. I don’t think it’s an accident that dialectic was embraced as a tool by the Surrealists and the Dadaists, who took a systematic approach to cultivating the irrational. In one of Antonin Artaud’s letters, we read the very exciting sentence: “Dialectics is the art of considering ideas from every conceivable point of view—it is a method of distributing ideas.” And Tristan Tzara may have gotten even closer to the truth: “The dialectic is an amusing mechanism which guides us—in a banal kind of way—to the opinions we had in the first place.” He’s right to call it banal, but it can also be hard to figure out what we already believe, and the switch point has a way of clarifying this. It can result in a philosophy of life, or it can take the form of an ad hoc trick, like Burgess and his dictionary. But we all end up with our own strategies for producing it, and we may not even have a choice. As Trotsky is supposed to have said: “You may not be interested in the dialectic, but the dialectic is interested in you.”

The power of the page

Note: I’m on vacation this week, so I’ll be republishing a few of my favorite posts from earlier in this blog’s run. This post originally appeared, in a slightly different form, on December 22, 2014.

Over the weekend, I found myself contemplating two very different figures from the history of American letters. The first is the bestselling nonfiction author Laura Hillenbrand, whose lifelong struggle with chronic fatigue syndrome compelled her to research and write Seabiscuit and Unbroken while remaining largely confined to her house for the last quarter of a century. (Wil S. Hylton’s piece on Hillebrand in The New York Times Magazine is absolutely worth a read—it’s the best author profile I’ve seen in a long time.) The other is the inventor and engineer Buckminster Fuller, whose life was itinerant as Hillebrand’s is stationary. There’s a page in E.J. Applewhite’s Cosmic Fishing, his genial look at his collaboration with Fuller on the magnum opus Synergetics, that simply reprints Fuller’s travel schedule for a representative two weeks in March: he flies from Philadelphia to Denver to Minneapolis to Miami to Washington to Harrisburg to Toronto, attending conferences and giving talks, to the point where it’s hard to see how he found time to get anything else done. Writing a coherent book, in particular, seemed like the least of his concerns; as Applewhite notes, Fuller’s natural element was the seminar, which allowed him to spin complicated webs of ideas in real time for appreciative listeners, and one of the greatest challenges of producing Synergetics lay in harnessing that energy in a form that could be contained within two covers.

At first glance, Hillenbrand and Fuller might seem to have nothing in common. One is a meticulous journalist, historian, and storyteller; the other a prodigy of worldly activity who was often reluctant to put his ideas down in any systematic way. But if they meet anywhere, it’s on the printed page—and I mean this literally. Hylton’s profile of Hillebrand is full of fascinating details, but my favorite passage describes how her constant vertigo has left her unable to study works on microfilm. Instead, she buys and reads original newspapers, which, in turn, has influenced the kinds of stories she tells:

Hillenbrand told me that when the newspaper arrived, she found herself engrossed in the trivia of the period—the classified ads, the gossip page, the size and tone of headlines. Because she was not hunched over a microfilm viewer in the shimmering fluorescent basement of a research library, she was free to let her eye linger on obscure details.

There are shades here of Nicholson Baker, who became so concerned over the destruction of library archives of vintage newspapers that he bought a literal ton of them with his life savings, and ended up writing an entire book, the controversial Human Smoke, based on his experience of reading press coverage of the events leading up to World War II day by day. And the serendipity that these old papers afforded was central to Hillebrand’s career: she first stumbled across the story of Louie Zamperini, the subject of Unbroken, on the opposite side of a clipping she was reading about Seabiscuit.

Fuller was similarly energized by the act of encountering ideas in printed form, with the significant difference that the words, in this case, were his own. Applewhite devotes a full chapter to Fuller’s wholesale revision of Synergetics after the printed galleys—the nearly finished proofs of the typeset book itself—had been delivered by their publisher. Authors aren’t supposed to make extensive rewrites in the galley stage; it’s so expensive to reset the text that writers pay for any major changes out of their own pockets. But Fuller enthusiastically went to town, reworking entire sections of the book in the margins, at a personal cost of something like $3,500 in 1975 dollars. And Applewhite’s explanation for this impulse is what caught my eye:

Galleys galvanize Fuller partly because of the large visual component of his imagination. The effect is reflexive: his imagination is triggered by what the eye frames in front of him. It was the same with manuscript pages: he never liked to turn them over or continue to another sheet. Page = unit of thought. So his mind was retriggered with every galley and its quite arbitrary increment of thought from the composing process.

The key word here is “quite arbitrary.” A sequence of pages—whether in a newspaper or in a galley proof—is an arbitrary grid laid on a sequence of ideas. Where the page break falls, or what ends up on the opposite side, is largely a matter of chance. And for both Fuller and Hillenbrand, the physical page itself becomes a carrier of information. It’s serendipitous, random, but no less real.

And it makes me reflect on what we give up when pages, as tangible objects, pass out of our lives. We talk casually about “web pages,” but they aren’t quite the same thing: now that many websites, including this one, offer visitors an infinite scroll, the effect is less like reading a book than like navigating the spool of paper that Kerouac used to write On the Road. Occasionally, a web page’s endlessness can be turned into a message in itself, as in the Clickhole blog post “The Time I Spent on a Commercial Whaling Ship Totally Changed My Perspective on the World,” which turns out to contain the full text of Moby-Dick. More often, though, we end up with a wall of text that destroys any possibility of accidental juxtaposition or structure. I’m not advocating a return to the practice of arbitrarily dividing up long articles into multiple pages, which is usually just an excuse to generate additional clicks. But the primacy of the page—with its arbitrary slice or junction of content—reminds us of why it’s still sometimes best to browse through a physical newspaper or magazine, or to look at your own work in printed form. At a time when we all have access to the same world of information, something as trivial as a page break or an accidental pairing of ideas can be the source of insights that have occurred to no one else. And the first step might be as simple as looking at something on paper.

Quote of the Day

If you are in a shipwreck and all the boats are gone, a piano top buoyant enough to keep you afloat that comes along makes a fortuitous life preserver. But this is not to say that the best way to design a life preserver is in the form of a piano top.

Tying the knot

McKenzie Funk’s recent piece in The New York Times Magazine on the wreck of the Kulluk, the doomed oil rig sent by Shell to drill an exploratory well in the Arctic Sea, is one of the most riveting stories I’ve read in a long time. The whole thing is full of twists and turns—I devoured it in a single sitting—but my favorite moment involves a simple knot. Faced with a rig with a broken emergency line, Craig Matthews, the chief engineer of the tugboat Alert, came up with a plan: they’d get close enough to grab the line with a grappling hook, reel it in, and tie it to their own tow cable with a bowline. After two tries, they managed to snag the line, “thicker than a man’s arm, a soggy dead weight.” Funk describes what happened next:

Now Matthews tried to orient himself. A knot he could normally tie with one hand without looking would have to be tackled by two people, chunk by chunk. The chief mate helped him lift the line again, and together they hurriedly bent it and forced the rabbit through the hole…Matthews had planned to do a second bend, just in case, but he was exhausted. “Is that it?” Matthews recalls the chief mate asking. His answer was to let the towline slide over the edge.

And although plenty of other things would go wrong later on, the knot held throughout all that followed.

The story caught my eye because it reminded me, as almost everything does these days, of the creative process. When you’re a writer, you generally hone your craft on smaller projects, short stories or essays that you can practically hold in one hand. Early on, it’s like learning to tie a bowline for the first time—as Brody does in Jaws—and it can be hard to even keep the ends straight, but sooner or later, you internalize the steps to the point where you can take them for granted. As soon as you tackle a larger project, though, you find that you suddenly need to stop and remember everything you thought you knew by heart. Most of us don’t think twice about how to tie our shoelaces, but if we were told to make the same knot in a rope the thickness of a fire hose, we’d have to think hard. A change in scale forces us to relearn the most basic tricks, and at first, we feel almost comically clumsy. That’s all the more true of a collaborative effort, like making a movie or staging a play, which can often feel like two people tying a knot together while being buffeted by wind and waves. (Technically, a novel or play is more like one big knot made up of many other knots, but maybe this analogy is strained enough as it is.)

Knots have long fascinated novelists, like Annie Proulx, perhaps because they’re the purest example of an abstract design intended to perform a functional task. As Buckminster Fuller points out in Synergetics, you can tie a loose knot in a rope spliced together successively from distinct kinds of fiber, like manila and cotton, and slip it from one end to the other: the materials change, but the knot stays the same. Fuller concludes, in his marvelously explicit and tangled prose: “The knot is not the rope; it is a weightless, mathematical, geometrical, metaphysically conceptual, pattern integrity tied momentarily into the rope by the knot-conceiving, weightless mind of the human conceiver—knot-former.” That’s true of a novel, too. You can, and sometimes do, revise every sentence of a story into a different form while leaving the overall pattern the same. Knots themselves can be used to transmit information, as in the Incan quipu, which record numbers and even syllables in the form of knotted cords. And Robert Graves has suggested that the Gordian knot encoded the name of a Phrygian god, which could only be untied by reading the message one letter at a time. Alexander the Great simply cut it with his sword—a solution that has occurred to more than one novelist frustrated by the mess he’s created.

You could write an entire essay on the metaphors inherent in knots, the language of which itself is rich with analogies: the phrase “the bitter end,” for instance, originates in ropeworking, referring to the end of the rope that is tied off. Most memorable is Fuller’s own suggestion that the ropeworker himself is a kind of thinking knot:

The metabolic flow that passes through a man is not the man. He is an abstract pattern integrity that is sustained through all his physical changes and processing, a knot through which pass the swift strands of concurrent ecological cycles—recycling transformations of solar energy.

And if we’re all simply knots passing through time, the prospect of untying and redoing that pattern is far more daunting than doing the same for even the most complicated novel. We’re all a little like Matthews on the deck of the Alert: we’d like to do a second bend to be safe, but sometimes we have no choice but to let the line slip over the side. That’s true of the small things, like sending out a story when we might prefer to noodle over it forever, and the large, like choosing a shape for your life that you hope will get the job done. And all we can really do is tie the knot we know best, let it go, and hang on to the bitter end.

The power of the page

Over the weekend, I found myself contemplating two very different figures from the history of American letters. The first is the bestselling nonfiction author Laura Hillenbrand, whose lifelong struggle with chronic fatigue syndrome compelled her to research and write Seabiscuit and Unbroken while remaining largely confined to her house for the last quarter of a century. (Wil S. Hylton’s piece on Hillebrand in The New York Times Magazine is absolutely worth a read—it’s the best author profile I’ve seen in a long time.) The other is the inventor and engineer Buckminster Fuller, whose life was itinerant as Hillebrand’s is stationary. There’s a page in E.J. Applewhite’s Cosmic Fishing, his genial look at his collaboration with Fuller on the magnum opus Synergetics, that simply reprints Fuller’s travel schedule for a representative two weeks in March: he flies from Philadelphia to Denver to Minneapolis to Miami to Washington to Harrisburg to Toronto, attending conferences and giving talks, to the point where it’s hard to see how he found time to get anything else done. Writing a coherent book, in particular, seemed like the least of his concerns; as Applewhite notes, Fuller’s natural element was the seminar, which allowed him to spin complicated webs of ideas in real time for appreciative listeners, and one of the greatest challenges of producing Synergetics lay in harnessing that energy in a form that could be contained within two covers.

At first glance, Hillenbrand and Fuller might seem to have nothing in common. One is a meticulous journalist, historian, and storyteller; the other a prodigy of worldly activity who was often reluctant to put his ideas down in any systematic way. But if they meet anywhere, it’s on the printed page—and I mean this literally. Hylton’s profile of Hillebrand is full of fascinating details, but my favorite passage describes how her constant vertigo has left her unable to study works on microfilm. Instead, she buys and reads original newspapers, which, in turn, has influenced the kinds of stories she tells:

Hillenbrand told me that when the newspaper arrived, she found herself engrossed in the trivia of the period—the classified ads, the gossip page, the size and tone of headlines. Because she was not hunched over a microfilm viewer in the shimmering fluorescent basement of a research library, she was free to let her eye linger on obscure details.

There are shades here of Nicholson Baker, who became so concerned over the destruction of library archives of vintage newspapers that he bought a literal ton of them with his life savings, and ended up writing an entire book, the controversial Human Smoke, based on his experience of reading press coverage of the events leading up to World War II day by day. And the serendipity that these old papers afforded was central to Hillebrand’s career: she first stumbled across the story of Louie Zamperini, the subject of Unbroken, on the opposite side of a clipping she was reading about Seabiscuit.

Fuller was similarly energized by the act of encountering ideas in printed form, with the significant difference that the words, in this case, were his own. Applewhite devotes a full chapter to Fuller’s wholesale revision of Synergetics after the printed galleys—the nearly finished proofs of the typeset book itself—had been delivered by their publisher. Authors aren’t supposed to make extensive rewrites in the galley stage; it’s so expensive to reset the text that writers pay for any major changes out of their own pockets. But Fuller enthusiastically went to town, reworking entire sections of the book in the margins, at a personal cost of something like $3,500 in 1975 dollars. And Applewhite’s explanation for this impulse is what caught my eye:

Galleys galvanize Fuller partly because of the large visual component of his imagination. The effect is reflexive: his imagination is triggered by what the eye frames in front of him. It was the same with manuscript pages: he never liked to turn them over or continue to another sheet. Page = unit of thought. So his mind was retriggered with every galley and its quite arbitrary increment of thought from the composing process.

The key word here is “quite arbitrary.” A sequence of pages—whether in a newspaper or in a galley proof—is an arbitrary grid laid on a sequence of ideas. Where the page break falls, or what ends up on the opposite side, is largely a matter of chance. And for both Fuller and Hillenbrand, the physical page itself becomes a carrier of information. It’s serendipitous, random, but no less real.

And it makes me reflect on what we give up when pages, as tangible objects, pass out of our lives. We talk casually about “web pages,” but they aren’t quite the same thing: now that many websites, including this one, offer visitors an infinite scroll, the effect is less like reading a book than like navigating the spool of paper that Kerouac used to write On the Road. Occasionally, a web page’s endlessness can be turned into a message in itself, as in the Clickhole blog post “The Time I Spent on a Commercial Whaling Ship Totally Changed My Perspective on the World,” which turns out to contain the full text of Moby-Dick. More often, though, we end up with a wall of text that destroys any possibility of accidental juxtaposition or structure. I’m not advocating a return to the practice of arbitrarily dividing up long articles into multiple pages, which is usually just an excuse to generate additional clicks. But the primacy of the page—with its arbitrary slice or junction of content—reminds us of why it’s still sometimes best to browse through a physical newspaper or magazine, or to look at your own work in printed form. At a time when we all have access to the same world of information, something as trivial as a page break or an accidental pairing of ideas can be the source of insights that have occurred to no one else. And the first step might be as simple as looking at something on paper.

Quote of the Day

Philosophy to be effective must be mechanically applied.

Masters of the earthworm, or the generalist’s dilemma

Over the past year or so, I’ve scaled back on the number of books I buy each month, mostly for reasons of shelf space. Every now and then, though, my eye will be caught by a sale or special event I can’t resist, which is how I ended up receiving a big carton last week from Better World Books. (As I’ve noted before, this is the best site for used books around, and a fantastic resource for filling in the gaps in your library.) The box contained what looks, at first, like a random assortment of titles: Strong Opinions, the aptly named collection of interviews and essays by Vladimir Nabokov; Art and Illusion by E.H. Gombrich, which was named one of the hundred best nonfiction books of the century by Modern Library; Cosmic Fishing, a short memoir by E.J. Applewhite about his collaboration with Buckminster Fuller on the book Synergetics; and best of all, Ernest Schwiebert’s magisterial two-volume Trout, which I’ve coveted for years. If it seems like a grab bag, that’s no accident: I really had my eye on Trout, which I ended up getting for half the price it goes for elsewhere, and the others were mostly there to fill out the order. But my choices here also say a lot about me and the kind of books and authors I find most appealing.

The most obvious common thread between all these books is that they lie somewhere at the intersection of art and science. Nabokov, of course, was an accomplished lepidopterist, and Strong Opinions concludes with a sampling of his scientific papers on butterflies. Art and Illusion is a work on the psychology of perception written by an art historian, and the back cover makes its intentions clear: “This book is directed to all who seek for a meeting ground between science and the humanities.” Fuller always occupied a peculiar position between that of engineer, crackpot, and mystic, and this comes through strongly through the eyes of his literary collaborator, who strikingly argues that Fuller’s primary vocation is that of a poet, and reveals that he briefly considered rewriting all of Synergetics in blank verse. And in Schwiebert’s hands, the humble trout becomes a lens through which he considers nearly all of human experience: in the first volume, he wears the hats of historian, literary critic, biologist, ecologist, and entomologist, and that’s before he even gets to the intricacies of rods, flies, and waders. As Schwiebert writes: “[Angling’s] skills are a perfect equilibrium between tradition, physical dexterity and grace, strength, logic, esthetics, our powers of observation, problem solving, perception, and the character of our experience and knowledge.”

In short, these are all books by or about generalists, original thinkers who understand that the divisions between categories of knowledge are porous, if not outright fictional, and who can draw freely on a wide range of disciplines. Yet these authors also share another, more subtle quality: a relentless focus on a single subject as a window onto all of the rest. Nabokov was as obsessed by his butterflies as Fuller was by the tetrahedron. Gombrich returns repeatedly to “the riddle of style,” or what it means when we say that we draw what we see, and Schwiebert, of course, loved trout. I wouldn’t go so far as to say that any of them became generalists by accident; it takes a certain inborn temperament, and an inhuman degree of patience and curiosity, to even attempt such a comprehensive vision. But it’s no accident that all four of these men—and most of the generalists we know and remember—arrived at their expansive vistas through the narrowest of gates. Occasionally, a thinker with global ambitions will begin by deliberately constraining his or her focus, in a kind of apprenticeship or training ground: Darwin spent long eight years studying the cirripedes, a kind of barnacle, in what Thomas Henry Huxley called “a piece of critical self-discipline.” He knew that you need to go deep before you can go really wide.

And that hasn’t changed. The entomologist Edward O. Wilson recently published a book entitled The Meaning of Human Existence, which would seem insufferably grandiose if he hadn’t already proven himself with decades of laborious work on the ants and other social insects. When we think of the intellectuals we respect, nearly all are men and women who made fundamental contributions to a single, clearly defined field before moving on to others. That’s the generalist’s dilemma: it’s hard to think in an original way about everything until you know one thing well. Otherwise, you end up seeming like a dilettante or worse. I’m acutely aware of my own shortcomings here: I’ve spent all my life trying to be a generalist, to the point of becoming a writer so I had an excuse to poke into whatever subjects I like, but I’ve rarely had the patience to drill down deeply. And while I’m content with my choice, I’m not sure I’d recommend it to anyone else. Hilaire Belloc once said that the best way for a writer to become famous was to concentrate on one subject, like the earthworm, for forty years: “When he is sixty, pilgrims will make a hollow path with their feet to the door of the world’s great authority on the earthworm. They will knock at his door and humbly beg to be allowed to see the Master of the Earthworm.” Belloc pointedly failed to take his own advice, but he has a point. We need to become masters of the earthworm before we become masters of the earth.

Books do furnish a life

When I was growing up in Castro Valley, California, one of the high points of any year was our annual library book sale. My local library was located conveniently across the street from my church, so on one magical weekend, I’d enter the parish hall to find row after row of folding tables stacked with discards and donations. In many ways, it was my first real taste of the joys of browsing: there wasn’t a good used bookstore in town, and I was still a few years away from taking the train up to Berkeley to dive into the stacks at Moe’s and Shakespeare and Company. Instead, I found countless treasures on those tables, and because each book cost just a few dollars, it encouraged exploration, risk, and serendipitous discoveries. Best of all was the final day, in which enterprising buyers could fill a shopping bag of books—a whole bag!—for just a couple of bucks. If you’re a certain kind of book lover, you know that this can be the best feeling in the world, and I still occasionally have dreams at night of making a similar haul at the perfect used bookshop.

Over time, though, the books I picked up were slowly dispersed, usually by a series of moves, so that only a few have followed me from California to Chicago. (Looking around my shelves now, the only books I can positively identify as having come from one of those sales are Dean Koontz’s Writing Popular Fiction and my complete set of Great Books of the Western World, which certainly counts as my greatest find—I vividly remember camping out in a corner to guard the volumes until the time came to drag them away.) It’s a cycle that has recurred repeatedly through my life, as I stumble across a new source of abundant cheap books, buy scores of them in a series of impulsive trips, then find myself faced with some hard choices at my next move. Over the course of seven years in New York, I probably spent several thousand dollars at the Strand, much of it in the legendary dollar bin, and when I moved, I donated twelve boxes to Goodwill, coming to maybe five hundred books that had briefly enriched my life before moving on. As Buckminster Fuller wrote about his own body:

I am not a thing—a noun. At eighty-five, I have taken in over a thousand tons of air, food, and water, which temporarily became my flesh and which progressively disassociated from me. You and I seem to be verbs—evolutionary processes.

A library, I’ve found, is a sort of organic being of its own, growing along with its user, taking in raw materials, retaining some while getting rid of others, and progressing ever closer to an ideal shape that changes, like the body, over time. It’s even more accurate to see a library as the result of a kind of editorial process. The bags of books I picked up when I was in my teens were like a first draft, ragged, messy, but a source of essential clay for the work to come. More drafts followed with every change of address, with the books that no longer spoke to me—or whose purpose had been filled in providing a few happy hours of browsing—standing aside to make room for others. A library moves asymptotically, like a novel, toward its finished form, and in the end, it starts to look like a portrait of the author. To mix analogies, it’s like a sculpture, or a collage, that finds its shape both through accretion and removal. I never could have assembled the library I have now through first principles: it’s the product of time, shifting interests, the urge in my programming to buy more books, and the constraints imposed by mobility and shelving. And although the result may puzzle others, to me, it feels like home.

Not surprisingly, I’ve become increasingly picky, even eccentric, when it comes to the books I buy. Over the last few weeks, I’ve gone to a number of book sales—at the Printers Row Lit Fest and the Open Books store in Chicago—that previously would have left me with several bags to bring home. Instead, I’ve emerged after hours of browsing with a handful of books whose titles bewilder even me: Hidden Images, Design With Climate, The Divining Rod, Ship Models. If I’m drawn increasingly to odd little books, it’s due in part to the fact that I’ve already filled up the shelves in my office, so I tend to favor books that I don’t think I’ll be able to find at my local library. Really, though, it’s because the books I buy now are devoted to filling existing gaps, like a draft of a novel in which the choices I can make are influenced by a long train of earlier decisions. It’s starting to feel like my life’s work, and I treat it accordingly. Every now and then, I’ll cast an eye over my shelves, and if a book doesn’t make me actively happy to see it there, off it goes. Each one that remains carries a reside of meaning or history, if only by capturing a memory of a day spent deep in the stacks. And unlike my other works, it won’t ever be complete, because on the day it’s finished, I will be, too.