Archive for the ‘Books’ Category

Fuller at the 92Y

I’m very excited to announce that I’ll be giving a two-part online talk on the life and work of Buckminster Fuller in partnership with the 92nd Street Y on May 13 and 20. It’s hosted through Roundtable, their virtual education platform, so anyone can attend. I expect that it will be the most comprehensive talk that I’ll ever give on Fuller—I plan to cover every important episode from my biography Inventor of the Future—and I’m hoping to attract a receptive audience. If you have a chance, I’d appreciate it very much if you could spread the word—and I hope to see some of you there!

Back to the Future

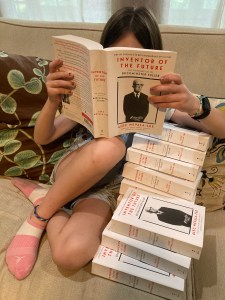

It’s hard to believe, but the paperback edition of Inventor of the Future: The Visionary Life of Buckminster Fuller is finally in stores today. As far as I’m concerned, this is the definitive version of this biography—it incorporates a number of small fixes and revisions—and it marks the culmination of a journey that started more than five years ago. It also feels like a milestone in an eventful writing year that has included a couple of pieces in the New York Times Book Review, an interview with the historian Richard Rhodes on Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer for The Atlantic online, and the usual bits and bobs elsewhere. Most of all, I’ve been busy with my upcoming biography of the Nobel Prize-winning physicist Luis W. Alvarez, which is scheduled to be published by W.W. Norton sometime in 2025. (Oppenheimer fans with sharp eyes and good memories will recall Alvarez as the youthful scientist in Lawrence’s lab, played by Alex Wolff, who shows Oppenheimer the news article announcing that the atom has been split. And believe me, he went on to do a hell of a lot more. I can’t wait to tell you about it.)

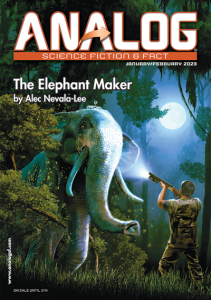

Ringing in the new

By any measure, I had a pretty productive year as a writer. My book Inventor of the Future: The Visionary Life of Buckminster Fuller was released after more than three years of work, and the reception so far has been very encouraging—it was named a New York Times Book Review Editors’ Choice, an Economist best book of the year, and, wildest of all, one of Esquire‘s fifty best biographies of all time. (My own vote would go to David Thomson’s Rosebud, his fantastically provocative biography of Orson Welles.) On the nonfiction front, I rounded out the year with pieces in Slate (on the misleading claim that Fuller somehow anticipated the principles of cryptocurrency) and the New York Times (on the remarkable British writer R.C. Sherriff and his wonderful novel The Hopkins Manuscript). Best of all, the latest issue of Analog features my 36,000-word novella “The Elephant Maker,” a revised and updated version of an unpublished novel that I started writing in my twenties. Seeing it in print, along with Inventor of the Future, feels like the end of an era for me, and I’m not sure what the next chapter will bring. But once I know, you’ll hear about it here first.

A Geodesic Life

After three years of work—and more than a few twists and turns—my latest book, Inventor of the Future: The Visionary Life of Buckminster Fuller, is finally here. I think it’s the best thing that I’ve ever done, or at least the one book that I’m proudest to have written. After last week’s writeup in The Economist, a nice review ran this morning in the New York Times, which is a dream come true, and you can check out excerpts today at Fast Company and Slate. (At least one more should be running this weekend in The Daily Beast.) If you want to hear more about it from me, I’m doing a virtual event today sponsored by the Buckminster Fuller Institute, and on Saturday August 13, I’ll be holding a discussion at the Oak Park Public Library with Sarah Holian of the Frank Lloyd Wright Trust, which will be also be available to view online. There’s a lot more to say here, and I expect to keep talking about Fuller for the rest of my life, but for now, I’m just delighted and relieved to see it out in the world at last.

Inventing the future

I realize that I’m well overdue for an update on my new book, Inventor of the Future: The Visionary Life of Buckminster Fuller, which is scheduled to be published by Dey Street Books / HarperCollins on August 2. Yesterday, I delivered my revisions to the copy edit, so I’ve essentially reached the end of a process that has lasted three long and challenging years. The result, I think, is the best thing I’ve ever done. It’s a big book—over six hundred pages including the back matter and index—but Fuller more than justifies it, and I hope that it will appeal to both his existing admirers and readers who are encountering him for the first time. (Even if you’re an obsessive Fuller fan, I can guarantee that there’s a lot here that you haven’t seen before.) I’m also delighted by the cover, which features a remarkable portrait of Fuller by Richard Avedon that has rarely been reproduced elsewhere. Obviously, I’ll have a lot more to say about this over the next few months, so check back soon for more!

Ben Bova (1932-2020)

Earlier this month, the legendary author and editor Ben Bova passed away in Florida. Bova famously took over Analog after the death of John W. Campbell, and he was the crucial figure in a transition that managed to honor the magazine’s tradition of hard science fiction while pushing into stranger, less predictable territory. By publishing stories like “The Gold at the Starbow’s End” by Frederik Pohl, “Hero” by Joe Haldeman, and “Ender’s Game” by Orson Scott Card, as well as important work by such authors as George R.R. Martin and Vonda N. McIntyre, Bova did more than anyone else to usher the Campbellian mode into the new era, and the result still embodies the genre’s possibilities for countless fans. I never met Bova in person, and I only had the chance to interview him once over the phone, but I was pleased to help out very slightly with his obituary in the New York Times. It’s a tribute that he richly deserved, and I hope that his example will endure well into the next generation of editors and writers.

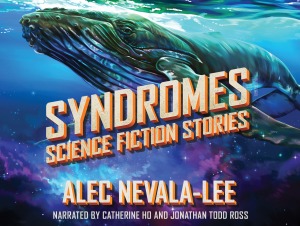

Listening to Syndromes

I’m pleased beyond words to announce that my audio short fiction collection Syndromes, which includes all thirteen of my stories from Analog Science Fiction and Fact, has just been released by Recorded Books. (It was originally scheduled to drop in June, but in light of recent developments, it became one of a handful of titles to come out before everything shut down on that end. I’m glad that it managed to appear just under the wire, and I’m especially delighted by the dazzling cover art by Will Lee.) The wonderful narrators Jonathan Todd Ross and Catherine Ho trade reading duties on “Ernesto,” “The Spires,” “The Whale God,” “The Last Resort,” “Kawataro,” “Cryptids,” “The Boneless One,” “Inversus,” “Stonebrood,” “The Voices,” “The Proving Ground,” and “At the Fall,” before joining forces at the end for a new version of my audio play “Retention,” which strikes me as the standout track. Every story has been revised to fit into a single interconnected timeline, which stretches from 1937 through the near future, and even if you’ve read some of them before, you’ll discover a few new surprises. You can purchase it at Amazon or stream it through Audible or Libro.fm, so I hope that some of you will check it out—and let me know what you think!

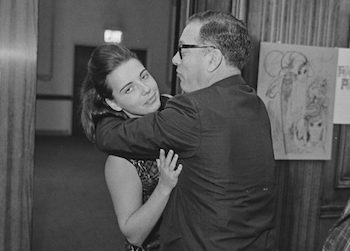

The books and the wall

Yesterday, I published an essay titled “Asimov’s Empire, Asimov’s Wall” on the website Public Books, in which I discuss Isaac Asimov’s history of groping and engaging in other forms of unwanted touching with women at conventions, in the workplace, and in private over the course of many decades. It’s a piece that I’ve had in mind for a long time, and I’ve come to think of it as a lost chapter of Astounding, which I might well have included in the book if I had delivered the final draft a few months later than I actually did. (I’m also very glad that the article includes the image reproduced above, which I found after going through thousands of photos in the Jay Kay Klein archive.) The response online so far has been overwhelming, including numerous firsthand accounts of his behavior, and I hope it leads to more stories about Asimov, as well as others. There’s a lot that I deliberately didn’t cover here, and it deserves to be taken further in the right hands.

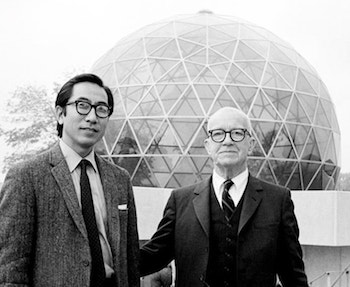

Shoji Sadao (1926-2019)

The architect Shoji Sadao—who worked closely with Buckminster Fuller and the sculptor Isamu Noguchi—passed away earlier this month in Tokyo. I’m briefly quoted in Sadao’s obituary in the New York Times, which draws attention to his largely unsung role in the careers of these two brilliant but demanding men. My contact with Sadao was limited to a few emails and one short phone conversation intended to set up an interview that I’m sorry will never happen, but I’ll be discussing his legacy at length in my upcoming biography of Fuller, and you’ll be hearing a lot more about him here.

Onward and upward

Next week, I’ll be attending the 77th World Science Fiction Convention in Dublin, Ireland, which promises to be a lot of fun. Here’s my schedule as it currently stands:

- Thursday August 15, 3pm—”Current Politics Reflected in SFF”—Dr. Harvey O’Brien (M), Susan Connolly, Dr Douglas Van Belle, Alec Nevala-Lee—”SFF is probably the genre that best mirrors present day society. If we examine SFF in both visual media and books, what can we learn about current politics playing out? What might future generations surmise about us?”

- Friday August 16, 11:30am—”Continuing Relevance of Older SF”—Sue Burke (M), Alec Nevala-Lee, Aliza Ben Moha, Robert Silverberg, Joe Haldeman—”We are in a new millennium, a literal Brave New World. Surely much of the fiction of the 20th century no longer holds relevance? The panel will discuss the fiction of the past and how it can still be relevant in the 21st century. What lessons from older authors – such as Orwell, Asimov, Butler, Delany, Kafka, and Atwood – can we apply to our app-loaded, social media-driven age?”

- Friday August 16, 2019, 5pm—”Comparable Futurist Movements”—Alec Nevala-Lee (M), Gillian Polack, Jeanine Tullos Hennig, Shweta Taneja—”How influenced by Afrofuturism are other world futurist movements such as Sinofuturism, Nippofuturism and Gulf futurism? Do they consider themselves a part of the same futurist tradition, or separate? The panel will discuss visions of the future from world cultures, how they are influenced by the root cultures they draw from, and how (if at all) they relate to Afrofuturism.”

- Saturday August 17, 2019, 2pm—Autographing

- Monday August 19, 2019, 10am—Kaffeeklatsch

- Monday August 19, 2019, 12:30pm—Reading

I might as well also mention that Astounding is up for the Hugo Award for Best Related Work—although the rest of the ballot is extremely formidable—and that it recently came out in paperback. (This new edition is virtually identical to the hardcover, but I took the opportunity to make a few small fixes and tweaks, and as far as I’m concerned, this is the definitive version.) And if you haven’t done so already, please check out the first three episodes of the wonderful Washington Post podcast Moonrise, which heavily draws on material from the book. Hope to see some of you soon!

Burrowing into The Tunnel

Last fall, it occurred to me that someone should write an essay on the parallels between the novel The Tunnel by William H. Gass, which was published in 1995, and the contemporary situation in America. Since nobody else seemed to be doing it, I figured that it might as well be me, although it was a daunting project even to contemplate—Gass’s novel is over six hundred pages long and famously impenetrable, and I knew that doing it justice would take at least three weeks of work. Yet it seemed like something that had to exist, so I wrote it up at the end of last year. For various reasons, it took a long time to see print, but it’s finally out now in the New York Times Book Review. It isn’t the kind of thing that I normally do, but it felt like a necessary piece, and I’m pretty proud of how it turned out. And if the intervening seven months don’t seem to have dated it at all, it only puts me in mind of what the radio host on The Simpsons once said about the DJ 3000 computer: “How does it keep up with the news like that?”

Love and Rockets

I’m delighted to share the news that Astounding is a 2019 Hugo Award Finalist for Best Related Work, along with a slate of highly deserving nominees. (The other finalists include Archive of Our Own, a project of the Organization for Transformative Works; the documentary The Hobbit Duology by Lindsay Ellis and Angelina Meehan; An Informal History of the Hugos by Jo Walton; The Mexicanx Initiative Experience at Worldcon 76 by Julia Rios, Libia Brenda, Pablo Defendini, and John Picacio; and Conversations on Writing by Ursula K. Le Guin and David Naimon. It’s a strong ballot, and I’m honored to be counted in such good company.) It feels like the high point of a journey that began with an announcement on this blog more than three years ago, and it isn’t over yet—I’m definitely going to be attending the World Science Fiction Convention in Dublin, which runs from August 15 to 19, and while I don’t know what the final outcome will be, I’m grateful to have made it even this far. The Hugos are an important part of the history that this book explores, and I’m thankful for the chance to be even a tiny piece of that story.

Art and Arcana

On Sunday, I got back from the Savannah Book Festival, which was a real pleasure. My event at Trinity United Methodist Church—which was the first time that I’ve ever spoken from a pulpit—went great, at least to my eyes, and I enjoyed talking to the science fiction fans who were kind enough to turn out on a rainy afternoon. (I also had the chance to meet a number of other writers, notably Mike Witwer, whose Dungeons & Dragons: Art and Arcana looks just incredible.) During my free time, I visited the Book Lady Bookstore, which I highly recommend, and the house of Juliette Gordon Low, the founder of the Girl Scouts of the USA, much to the delight of my daughter, who recently joined the Daises. And I’m happy to note that my talk is scheduled to air on BookTV on C-SPAN2 this Saturday at 5:35pm ET, followed by an encore presentation early the following morning. (You can watch it online here.)

In the meantime, I have a few other upcoming events that might be worth mentioning. On Saturday February 23, I’ll be holding a second session of my fiction workshop, “Writing Science Fiction that Sells,” at Mary Anne Mohanraj’s makerspace in Oak Park, Illinois. The first class went better than I could have hoped, and I’d love to see some new faces there. (For the record, most of the guidelines that I plan to cover—clarity, coming up with ideas, structuring the plot as a series of objectives, managing the information that the reader receives—apply to all kinds of writing, although they present particular challenges in science fiction and fantasy.) I’m also going to be appearing with the editor and critic Gary K. Wolfe on Monday February 25 at the Blackstone branch of the Chicago Public Library, where we’ll be discussing Astounding as part of One Book, One Chicago. Please spread the word to anyone who might be interested—I hope to see some of you soon!

Sci-Fi Strawberry in Savannah

I’m heading out this morning to Savannah, Georgia for the Savannah Book Festival, where I’ll be appearing this Saturday at 4 pm at Trinity United Methodist Church to discuss Astounding. (As it happens, L. Ron Hubbard lived in Savannah for a period of time in the late forties while he was developing the mental health therapy that became known as dianetics, and I plan to briefly explore this local connection, as well as other aspects of the book that recently scored a big endorsement from a certain bearded fantasy writer.) I hope to see some of you there in person—perhaps at Leopold’s Ice Cream, which will be serving Sci-Fi Strawberry this weekend in honor of the book—and if you can’t make it, my event is scheduled to air eventually on BookTV on C-SPAN 2. And please keep an eye on this blog, where I expect to have a few other announcements soon. Stay tuned!

Visions of tomorrow

As I’ve mentioned here before, one of my few real regrets about Astounding is that I wasn’t able to devote much room to discussing the artists who played such an important role in the evolution of science fiction. (The more I think about it, the more it seems to me that their collective impact might be even greater than that of any of the writers I discuss, at least when it comes to how the genre influenced and was received by mainstream culture.) Over the last few months, I’ve done my best to address this omission, with a series of posts on such subjects as Campbell’s efforts to improve the artwork, his deliberate destruction of the covers of Unknown, and his surprising affection for the homoerotic paintings of Alejandro Cañedo. And I can reveal now that this was all in preparation for a more ambitious project that has been in the works for a while—a visual essay on the art of Astounding and Unknown that has finally appeared online in the New York Times Book Review, with the highlights scheduled to be published in the print edition this weekend. It took a lot of time and effort to put it together, especially by my editors, and I’m very proud of the result, which honors the visions of such artists as H.W. Wesso, Howard V. Brown, Hubert Rogers, Manuel Rey Isip, Frank Kelly Freas, and many others. It stands on its own, but I’ve come to think of it as an unpublished chapter from my book that deserves to be read alongside its longer companion. As I note in the article, it took years for the stories inside the magazine to catch up to the dreams of its readers, but the artwork was often remarkable from the beginning. And if you want to know what the fans of the golden age really saw when they imagined the future, the answer is right here.

The writing in the dust

Note: I’m taking some time off for the holidays, so I’m republishing a few pieces from earlier in this blog’s run. This post originally appeared, in a slightly different form, on November 22, 2017.

About a year ago, I found myself thinking at length about what might well be the most moving passage in the entire Bible. It’s the scene in the Gospel of John in which the Pharisees, hoping to trap Jesus, bring forward a woman taken in adultery and ask him if she should be stoned according to the law, only to hear him respond: “Whoever is sinless in this crowd should go ahead and throw the first stone.” After the other onlookers drift off one by one, embarrassed, leaving just the woman behind, Jesus asks if anyone has condemned her. When she answers no, he says: “I don’t condemn you either. You’re free to go, but from now on, no more sinning.” (The story was memorably, if freely, adapted as one of the most powerful scenes in Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ.) In The Acts of Jesus, the Jesus Seminar writes of the passage:

The earliest ancient manuscripts of John do not have it, and modern scholars are virtually unanimous in concluding that it was not an original part of the Fourth Gospel…An impartial evaluation of the story has been impeded by its preservation as part of the Gospel of John…The fundamental question is whether this anecdote is a fragment that survived from an otherwise unknown gospel. Had it been discovered as a separate piece of papyrus, it would have attracted serious scholarly attention in its own right.

In the end, the seminar endorses it mildly, less as a real incident than as a reflection of what we know about Jesus himself, and the companion volume The Five Gospels includes the remarkable line: “While the Fellows agreed that the words did not originate in their present form with Jesus, they nevertheless assigned the words and story to a special category of things they wish Jesus had said and done.”

I feel the same way. But I haven’t even mentioned the one detail that has always struck me—and many other readers—the most. When the Pharisees first pose their question, Jesus doesn’t answer right away. Instead, he stoops down and silently draws on the ground with his finger. He responds only after they insist on a reply, and then he bends down to write in the dust again. It’s impossible to read this without wondering what he might have been writing, and nearly three centuries ago, the biblical commentator Matthew Henry did as good a job of summarizing the possibilities as anyone could:

It is impossible to tell, and therefore needless to ask, what he wrote; but this is the only mention made in the gospels of Christ’s writing…Some think they have a liberty of conjecture as to what he wrote here. Grotius says, It was some grave weighty saying, and that it was usual for wise men, when they were very thoughtful concerning any thing, to do so. Jerome and Ambrose suppose he wrote, Let the names of these wicked men be written in the dust. Others this, The earth accuses the earth, but the judgment is mine. Christ by this teaches us to be slow to speak when difficult cases are proposed to us, not quickly to shoot our bolt; and when provocations are given us, or we are bantered, to pause and consider before we reply; think twice before we speak once.

That last line seems reasonable enough, and Henry concludes: “He did as it were look another way, to show that he was not willing to take notice of their address, saying, in effect, Who made me a judge or a divider?”

And the passage, authentic or not, is also precious as one of the few everyday actions of Jesus that have been passed down to us. I’ve spoken elsewhere of a gospel of nouns and verbs, but nearly all of it occurs in Jesus’s words, not in descriptions of him preserved by others. Jesus writes on the ground; he falls asleep in a boat; he feels hungry; he breaks bread and pours wine; he weeps. There isn’t much more. Part of this reflects the fact that the gospels emerged from an oral tradition, but it also testifies to its debt to its literary predecessors. In his great book Mimesis, Erich Auerbach writes of the Old Testament story of the binding of Isaac:

In this atmosphere it is unthinkable that an implement, a landscape through which the travelers passed, the servingmen, or the ass, should be described, that their origin or descent or material or appearance or usefulness should be set forth in terms of praise; they do not even admit an adjective: they are serving-men, ass, wood, and knife, and nothing else, without an epithet; they are there to serve the end which God has commanded; what in other respects they were, are, or will be, remains in darkness. A journey is made, because God has designated the place where the sacrifice is to be performed; but we are told nothing about the journey except that it took three days, and even that we are told in a mysterious way: Abraham and his followers rose “early in the morning” and “went unto” the place of which God had told him; on the third day he lifted up his eyes and saw the place from afar. That gesture is the only gesture, is indeed the only occurrence during the whole journey, of which we are told…It is as if, while he traveled on, Abraham had looked neither to the right nor to the left, had suppressed any sign of life in his followers and himself save only their footfalls.

At first glance, this style might seem primitive compared to that of the Iliad or the Odyssey, but as Auerbach points out, its effect on its audience goes much deeper than what we find in Homer:

The world of the Scripture stories is not satisfied with claiming to be a historically true reality—it insists that it is the only real world, is destined for autocracy. All other scenes, issues, and ordinances have no right to appear independently of it, and it is promised that all of them, the history of all mankind, will be given their due place within its frame, will be subordinated to it. The Scripture stories do not, like Homer’s, court our favor, they do not flatter us that they may please us and enchant us—they seek to subject us, and if we refuse to be subjected we are rebels…Far from seeking, like Homer, merely to make us forget our own reality for a few hours, it seeks to overcome our reality: we are to fit our own life into its world, feel ourselves to be elements in its structure of universal history.

This is the tradition to which Jesus—a historical person who feels much closer to many of us than the distant, shadowy figure of Abraham—was subordinated by the author of the gospels. As a literary strategy, it was a masterstroke, and it went a long way toward enabling Jesus to strike up an existence in the inner lives of so many. (Which doesn’t mean that its virtues are obvious. Norman Mailer once said of the gospels: “Where you don’t have a wonderful sentence, what you get is some pretty dull prose and a contradictory, almost hopeless way of telling the story.”) It also means, for better or worse, that Jesus can mean all things to all people. We no longer see him clearly, and he’s being used even as I write this to justify all forms of belief and behavior. My version of him is no more legitimate than that of anyone else. But I prefer to believe in the man who drew that line in the sand.

Updike’s ladder

Note: I’m taking the day off, so I’m republishing a post that originally appeared, in a slightly different form, on September 13, 2017.

Last year, the author Anjali Enjeti published an article in The Atlantic titled “Why I’m Still Trying to Get a Book Deal After Ten Years.” If just reading those words makes your palms sweat and puts your heart through a few sympathy palpitations, congratulations—you’re a writer. No matter where you might be in your career, or what length of time you mentally insert into that headline, you can probably relate to what Enjeti writes:

Ten years ago, while sitting at my computer in my sparsely furnished office, I sent my first email to a literary agent. The message included a query letter—a brief synopsis describing the personal-essay collection I’d been working on for the past six years, as well as a short bio about myself. As my third child kicked from inside my pregnant belly, I fantasized about what would come next: a request from the agent to see my book proposal, followed by a dream phone call offering me representation. If all went well, I’d be on my way to becoming a published author by the time my oldest child started first grade.

“Things didn’t go as planned,” Enjeti says dryly, noting that after landing and leaving two agents, she’s been left with six unpublished manuscripts and little else to show for it. She goes on to share the stories of other writers in the same situation, including Michael Bourne of Poets & Writers, who accurately calls the submission process “a slow mauling of my psyche.” And Enjeti wonders: “So after sixteen years of writing books and ten years of failing to find a publisher, why do I keep trying? I ask myself this every day.”

It’s a good question. As it happens, I first encountered her article while reading the authoritative biography Updike by Adam Begley, which chronicles a literary career that amounts to the exact opposite of the ones described above. Begley’s account of John Updike’s first acceptance from The New Yorker—just months after his graduation from Harvard—is like lifestyle porn for writers:

He never forgot the moment when he retrieved the envelope from the mailbox at the end of the drive, the same mailbox that had yielded so many rejection slips, both his and his mother’s: “I felt, standing and reading the good news in the midsummer pink dusk of the stony road beside a field of waving weeds, born as a professional writer.” To extend the metaphor…the actual labor was brief and painless: he passed from unpublished college student to valued contributor in less than two months.

If you’re a writer of any kind, you’re probably biting your hand right now. And I haven’t even gotten to what happened to Updike shortly afterward:

A letter from Katharine White [of The New Yorker] dated September 15, 1954 and addressed to “John H. Updike, General Delivery, Oxford,” proposed that he sign a “first-reading agreement,” a scheme devised for the “most valued and most constant contributors.” Up to this point, he had only one story accepted, along with some light verse. White acknowledged that it was “rather unusual” for the magazine to make this kind of offer to a contributor “of such short standing,” but she and Maxwell and Shawn took into consideration the volume of his submissions…and their overall quality and suitability, and decided that this clever, hard-working young man showed exceptional promise.

Updike was twenty-two years old. Even now, more than half a century later and with his early promise more than fulfilled, it’s hard to read this account without hating him a little. Norman Mailer—whose debut novel, The Naked and the Dead, appeared when he was twenty-five—didn’t pull any punches in “Some Children of the Goddess,” an essay on his contemporaries that was published in Esquire in 1963: “[Updike’s] reputation has traveled in convoy up the Avenue of the Establishment, The New York Times Book Review, blowing sirens like a motorcycle caravan, the professional muse of The New Yorker sitting in the Cadillac, membership cards to the right Fellowships in his pocket.” Even Begley, his biographer, acknowledges the singular nature of his subject’s rise:

It’s worth pausing here to marvel at the unrelieved smoothness of his professional path…Among the other twentieth-century American writers who made a splash before their thirtieth birthday…none piled up accomplishments in as orderly a fashion as Updike, or with as little fuss…This frictionless success has sometimes been held against him. His vast oeuvre materialized with suspiciously little visible effort. Where there’s no struggle, can there be real art? The Romantic notion of the tortured poet has left us with a mild prejudice against the idea of art produced in a calm, rational, workmanlike manner (as he put it, “on a healthy basis of regularity and avoidance of strain”), but that’s precisely how Updike got his start.

Begley doesn’t mention that the phrase “regularity and avoidance of strain” is actually meant to evoke the act of defecation, but even this provides us with an odd picture of writerly contentment. As Dick Hallorann says in The Shining, the best movie about writing ever made: “You got to keep regular, if you want to be happy.”

If there’s a larger theme here, it’s that the sheer productivity and variety of Updike’s career—with its reliable production of uniform hardcover editions over the course of five decades—are inseparable from the “orderly” circumstances of his rise. Updike never lacked a prestigious venue for his talents, which allowed him to focus on being prolific. Writers whose publication history remains volatile and unpredictable, even after they’ve seen print, don’t always have the luxury of being so unruffled, and it can affect their work in ways that are almost subliminal. (A writer can’t survive ten years of chasing after a book deal without spending the entire time convinced that he or she is on the verge of a breakthrough, anticipating an ending that never comes, which may partially account for the prevalence in literary fiction of frustration and unresolved narratives. It also explains why it helps to be privileged enough to fail for years.) The short answer to Begley’s question is that struggle is good for a writer, but so is success, and you take what you can get, even as you’re transformed by it. I think on a monthly basis of what Nicholson Baker writes of Updike in his tribute U and I:

I compared my awkward public self-promotion too with a documentary about Updike that I saw in 1983, I believe, on public TV, in which, in one scene, as the camera follows his climb up a ladder at his mother’s house to put up or take down some storm windows, in the midst of this tricky physical act, he tosses down to us some startlingly lucid little felicity, something about “These small yearly duties which blah blah blah,” and I was stunned to recognize that in Updike we were dealing with a man so naturally verbal that he could write his fucking memoirs on a ladder!

We’re all on that ladder, including Enjeti, who I’m pleased to note finally scored her book deal—she has an essay collection in the works from the University of Georgia Press. Some are on their way up, some are headed down, and some are stuck for years on the same rung. But you never get anywhere if you don’t try to climb.

The unfinished lives

Yesterday, the New York Times published a long profile of Donald Knuth, the legendary author of The Art of Computer Programming. Knuth is eighty now, and the article by Siobhan Roberts offers an evocative look at an intellectual giant in twilight:

Dr. Knuth usually dresses like the youthful geek he was when he embarked on this odyssey: long-sleeved T-shirt under a short-sleeved T-shirt, with jeans, at least at this time of year…Dr. Knuth lives in Stanford, and allowed for a Sunday visitor. That he spared an entire day was exceptional—usually his availability is “modulo nap time,” a sacred daily ritual from 1 p.m. to 4 p.m. He started early, at Palo Alto’s First Lutheran Church, where he delivered a Sunday school lesson to a standing-room-only crowd.

This year marks the fiftieth anniversary of the publication of the first volume of Knuth’s most famous work, which is still incomplete. Knuth is busy writing the fourth installment, one fascicle at a time, although its most recent piece has been delayed “because he keeps finding more and more irresistible problems that he wants to present.” As Roberts writes: “Dr. Knuth’s exacting standards, literary and otherwise, may explain why his life’s work is nowhere near done. He has a wager with Sergey Brin, the co-founder of Google and a former student…over whether Mr. Brin will finish his Ph.D. before Dr. Knuth concludes his opus…He figures it will take another twenty-five years to finish The Art of Computer Programming, although that time frame has been a constant since about 1980.”

Knuth is a prominent example, although far from the most famous, of a literary and actuarial phenomenon that has grown increasingly familiar—an older author with a projected work of multiple volumes, published one book at a time, that seems increasingly unlikely to ever see completion. On the fiction side, the most noteworthy case has to be that of George R.R. Martin, who has been fielding anxious inquiries from fans for most of the last decade. (In an article that appeared seven long years ago in The New Yorker, Laura Miller quotes Martin, who was only sixty-three at the time: “I’m still getting e-mail from assholes who call me lazy for not finishing the book sooner. They say, ‘You better not pull a Jordan.’”) Robert A. Caro is still laboring over what he hopes will be the final volume of his biography of Lyndon Johnson, and mortality has become an issue not just for him, but for his longtime editor, as we read in Charles McGrath’s classic profile in the Times:

Robert Gottlieb, who signed up Caro to do The Years of Lyndon Johnson when he was editor in chief of Knopf, has continued to edit all of Caro’s books, even after officially leaving the company. Not long ago he said he told Caro: “Let’s look at this situation actuarially. I’m now eighty, and you are seventy-five. The actuarial odds are that if you take however many more years you’re going to take, I’m not going to be here.”

That was six years ago, and both men are still working hard. But sometimes a writer has no choice but to face the inevitable. When asked about the concluding fifth volume of his life of Picasso, with the fourth one still on the way, the biographer John Richardson said candidly: “Listen, I’m ninety-one—I don’t think I have time for that.”

I don’t have the numbers to back this up, but such cases—or at least the public attention that they inspire—seem to be growing more common these days, on account of some combination of lengthening lifespans, increased media coverage of writers at work, and a greater willingness from publishers to agree to multiple volumes in the first place. The subjects of such extended commitments tend to be monumental in themselves, in order to justify the total investment of the writer’s own lifetime, and expanding ambitions are often to blame for blown deadlines. Martin, Caro, and Knuth all increased the prospective number of volumes after their projects were already underway, or as Roberts puts it: “When Dr. Knuth started out, he intended to write a single work. Soon after, computer science underwent its Big Bang, so he reimagined and recast the project in seven volumes.” And this “recasting” seems particularly common in the world of biographies, as the author discovers more material that he can’t bear to cut. The first few volumes may have been produced with relative ease, but as the years pass and anticipation rises, the length of time it takes to write the next installment grows, until it becomes theoretically infinite. Such a radical change of plans, which can involve extending the writing process for decades, or even beyond the author’s natural lifespan, requires an indulgent publisher, university, or other benefactor. (John Richardson’s book has been underwritten by nothing less than the John Richardson Fund for Picasso Research, which reminds me of what Homer Simpson said after being informed that he suffered from Homer Simpson syndrome: “Oh, why me?”) And it may not be an accident that many of the examples that first come to mind are white men, who have the cultural position and privilege to take their time.

It isn’t hard to understand a writer’s reluctance to let go of a subject, the pressures on a book being written in plain sight, or the tempting prospect of working on the same project forever. And the image of such authors confronting their mortality in the face of an unfinished book is often deeply moving. One of the most touching examples is that of Joseph Needham, whose Science and Civilization in China may have undergone the most dramatic expansion of them all, from an intended single volume to twenty-seven and counting. As Kenneth Girdwood Robinson writes in a concluding posthumous volume:

The Duke of Edinburgh, Chancellor of the University of Cambridge, visited The Needham Research Institute, and interested himself in the progress of the project. “And how long will it take to finish it?” he enquired. On being given a rather conservative answer, “At least ten years,” he exclaimed, “Good God, man, Joseph will be dead before you’ve finished,” a very true appreciation of the situation…In his closing years, though his mind remained lucid and his memory astonishing, Needham had great difficulty even in moving from one chair to another, and even more difficulty in speaking and in making himself understood, due to the effect of the medicines he took to control Parkinsonism. But a secretary, working closely with him day by day, could often understand what he had said, and could read what he had written, when others were baffled.

Needham’s decline eventually became impossible to ignore by those who knew him best, as his biographer Simon Winchester writes in The Man Who Loved China: “It was suggested that, for the first time in memory, he take the day off. It was a Friday, after all: he could make it a long weekend. He could charge his batteries for the week ahead. ‘All right,’ he said. ‘I’ll stay at home.’” He died later that day, with his book still unfinished. But it had been a good life.