Posts Tagged ‘Analog Science Fiction and Fact’

Ringing in the new

By any measure, I had a pretty productive year as a writer. My book Inventor of the Future: The Visionary Life of Buckminster Fuller was released after more than three years of work, and the reception so far has been very encouraging—it was named a New York Times Book Review Editors’ Choice, an Economist best book of the year, and, wildest of all, one of Esquire‘s fifty best biographies of all time. (My own vote would go to David Thomson’s Rosebud, his fantastically provocative biography of Orson Welles.) On the nonfiction front, I rounded out the year with pieces in Slate (on the misleading claim that Fuller somehow anticipated the principles of cryptocurrency) and the New York Times (on the remarkable British writer R.C. Sherriff and his wonderful novel The Hopkins Manuscript). Best of all, the latest issue of Analog features my 36,000-word novella “The Elephant Maker,” a revised and updated version of an unpublished novel that I started writing in my twenties. Seeing it in print, along with Inventor of the Future, feels like the end of an era for me, and I’m not sure what the next chapter will bring. But once I know, you’ll hear about it here first.

Ben Bova (1932-2020)

Earlier this month, the legendary author and editor Ben Bova passed away in Florida. Bova famously took over Analog after the death of John W. Campbell, and he was the crucial figure in a transition that managed to honor the magazine’s tradition of hard science fiction while pushing into stranger, less predictable territory. By publishing stories like “The Gold at the Starbow’s End” by Frederik Pohl, “Hero” by Joe Haldeman, and “Ender’s Game” by Orson Scott Card, as well as important work by such authors as George R.R. Martin and Vonda N. McIntyre, Bova did more than anyone else to usher the Campbellian mode into the new era, and the result still embodies the genre’s possibilities for countless fans. I never met Bova in person, and I only had the chance to interview him once over the phone, but I was pleased to help out very slightly with his obituary in the New York Times. It’s a tribute that he richly deserved, and I hope that his example will endure well into the next generation of editors and writers.

The Return of “Retention”

Back in 2017, the audio anthology series The Outer Reach released an episode based on my dystopian two-person play “Retention,” which was performed by Aparna Nancherla and Echo Kellum. It’s one of my personal favorites of all my work—I talk about its origins here—and I’ve been delighted to see it come back over the last few months in no fewer than three different forms. The original recording, which was behind a paywall for years, is now available to stream for free through the network Maximum Fun. A wonderful new rendition narrated by Jonathan Todd Ross and Catherine Ho is included in my audio short story collection Syndromes. Perhaps best of all, the print adaptation appears in the July/August 2020 issue of Analog Science Fiction & Fact, which is on sale now. Because I’m hard at work on my current book project, this will probably be my last story in Analog for a while, and I can’t think of a better way to close out my recent run than with “Retention.” I’m very proud of all three versions, which interpret the same underlying text with intriguingly varied results, and I hope you’ll check at least one of them out.

Listening to Syndromes

I’m pleased beyond words to announce that my audio short fiction collection Syndromes, which includes all thirteen of my stories from Analog Science Fiction and Fact, has just been released by Recorded Books. (It was originally scheduled to drop in June, but in light of recent developments, it became one of a handful of titles to come out before everything shut down on that end. I’m glad that it managed to appear just under the wire, and I’m especially delighted by the dazzling cover art by Will Lee.) The wonderful narrators Jonathan Todd Ross and Catherine Ho trade reading duties on “Ernesto,” “The Spires,” “The Whale God,” “The Last Resort,” “Kawataro,” “Cryptids,” “The Boneless One,” “Inversus,” “Stonebrood,” “The Voices,” “The Proving Ground,” and “At the Fall,” before joining forces at the end for a new version of my audio play “Retention,” which strikes me as the standout track. Every story has been revised to fit into a single interconnected timeline, which stretches from 1937 through the near future, and even if you’ve read some of them before, you’ll discover a few new surprises. You can purchase it at Amazon or stream it through Audible or Libro.fm, so I hope that some of you will check it out—and let me know what you think!

“At the Fall” and Beyond

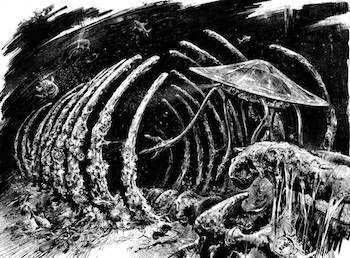

The May/June issue of Analog Science Fiction and Fact includes my new novelette “At the Fall,” a big excerpt of which you can read now on the magazine’s official site. It’s one of my favorite stories that I’ve ever written, and I’m especially pleased by the interior illustration by Eldar Zakirov, pictured above, which you can see in greater detail here. I don’t think I’ll have the chance to write up the kind of extended account of this story’s conception that I’ve provided for other works in the past, but if you’re curious about its origins, Analog has posted a fun conversation on its blog in which I talk about it with Frank Wu, the author of “In the Absence of Instructions to the Contrary,” which appeared in the magazine a few years ago. (Our stories have a number of interesting parallels that only came to light after I wrote and submitted mine, and I think that the result is a nice case study of what happens when two writers end up independently pursuing a similar idea.) There’s also a thoughtful editorial by former Analog editor Stanley Schmidt about his relationship with John W. Campbell, inspired by a panel that we held at last year’s World Science Fiction Convention. Enjoy!

Optimizing the future

Note: To celebrate the World Science Fiction Convention this week in San Jose, I’m republishing a few of my favorite pieces on various aspects of the genre. This post originally appeared, in a slightly different form, on August 10, 2017.

Last year, an online firestorm erupted over a ten-page memo written by James Damore, a twenty-eight-year-old software engineer at Google. Titled “Google’s Ideological Echo Chamber,” it led to its author being fired a few days later, and the furor took a long time to die down. (Damore filed a class action lawsuit against the company, and his case became a cause célèbre in exactly the circles that you’d expect.) In his memo, Damore essentially argues that the acknowledged gender gap in management and engineering roles at tech firms isn’t due to bias, but to “the distribution of preferences and abilities of men and women in part due to biological causes.” In women, these differences include “openness directed towards feelings and aesthetics rather than ideas,” “extraversion expressed as gregariousness rather than assertiveness,” “higher agreeableness,” and “neuroticism,” while men have a “higher drive for status” that leads them to take positions demanding “long, stressful hours that may not be worth it if you want a balanced and fulfilling life.” He summarizes:

I’m not saying that all men differ from women in the following ways or that these differences are “just.” I’m simply stating that the distribution of preferences and abilities of men and women differ in part due to biological causes and that these differences may explain why we don’t see equal representation of women in tech and leadership. Many of these differences are small and there’s significant overlap between men and women, so you can’t say anything about an individual given these population level distributions.

Damore quotes a decade-old research paper, which I suspect that he first encountered through the libertarian site Quillette, stating that as “society becomes more prosperous and more egalitarian, innate dispositional differences between men and women have more space to develop and the gap that exists between men and women in their personality becomes wider.” And he concludes: “We need to stop assuming that gender gaps imply sexism.”

When I first heard about the Damore case, it immediately rang a bell. Way back in 1968, a science fiction fan named Ron Stoloff attended the World Science Fiction Convention in Berkeley, where he was disturbed both by the lack of diversity and by the presence of at least one fan costumed as Lt. Uhura in blackface. He wrote up his thoughts in an essay titled “The Negro and Science Fiction,” which was published the following year in the fanzine The Vorpal Sword. (I haven’t been able to track down the full issue, but you can find the first page of his article here.) On May 1, 1969, the editor John W. Campbell wrote Stoloff a long letter objecting to the argument and to the way that he had been characterized. It’s a fascinating document that I wish I could quote in full, but the most revealing section comes after Campbell asks rhetorically: “Look guy—do some thinking about this. How many Negro authors are there in science fiction?” He then answers his own question:

Now consider what effect a biased, anti-Negro editor could have on that. Manuscripts come in by mail from all over the world…I haven’t the foggiest notion what most of the authors look like—and I never yet heard of an editor who demanded a photograph of an author before he’d print his work! Nor demanded a notarized document proving he was write.

If Negro authors are extremely few—it’s solely because extremely few Negroes both wish to, and can, write in open competition. There isn’t any possible field of endeavor where race, religion, and sex make less difference. If there aren’t any individuals of a particular group in the authors’ column—it’s because either they didn’t want to, or weren’t able to. It’s got to be unbiased by the very nature of the process of submission.

Campbell’s argument is fundamentally the same as Damore’s. It states that the lack of black writers in the pages of Analog, like the underrepresentation of women in engineering roles at Google, isn’t due to bias, but because “either they didn’t want to, or weren’t able to.” (Campbell, like Damore, makes a point of insisting elsewhere that he’s speaking of the statistical description of the group as a whole, not of individuals, which strikes him as a meaningful distinction.) Earlier in the letter, however, Campbell inadvertently suggests another explanation for why “Negro authors are extremely few,” and it doesn’t have anything to do with ability:

Think about it a bit, and you’ll realize why there is so little mention of blacks in science fiction; we see no reason to go saying “Lookee lookee lookee! We’re using blacks in our stories! See the Black Man! See him in a spaceship!”

It is my strongly held opinion that any Black should be thrown out of any story, spaceship, or any other place—unless he’s a black man. That he’s got no business there just because he’s black, but every right there if he’s a man. (And the masculine embraces the feminine; Lt. Uhura is portrayed as no clinging vine, and not given to the whimper, whinny, and whine type behavior. She earned her place by competence—not by having a black skin.)

As I’ve noted elsewhere, there are two implications here. The first is that all protagonists should be white males by default, while the second is that black heroes have to “earn” their presence in the magazine, which, given the hundreds of cardboard “competent men” that Campbell featured over the years, is laughable in itself.

It never seems to have occurred to Campbell that the dearth of minority writers in the genre might have been caused by a lack of characters who looked like them, as well as by similar issues in the fandom, and he never believed that he had the ability or the obligation to address the situation as an editor. (Elsewhere in the same letter, he writes: “What I am against—and what has been misinterpreted by a number of people—is the idea that any member of any group has any right to preferential treatment because he is a member.”) Left to itself, the scarcity of minority voices and characters was a self-perpetuating cycle that made it easy to argue that interest and ability were to blame. The hard part about encouraging diversity in science fiction, or anywhere else, is that it doesn’t happen by accident. It requires systematic, conscious effort, and the payoff might not be visible for years. That’s as hard and apparently unrewarding for a magazine that worries mostly about managing its inventory from one month to the next as it is for a technology company focused on yearly or quarterly returns. If Campbell had really wanted to see more black writers in Analog in the late sixties, he should have put more black characters in the magazine in the early forties. You could excuse this by saying that he had different objectives, and that it’s unfair to judge him in retrospect, but it’s equally true that it was a choice that he could have made, but didn’t. And science fiction was the poorer for it. In his memo, Damore writes:

Philosophically, I don’t think we should do arbitrary social engineering of tech just to make it appealing to equal portions of both men and women. For each of these changes, we need principled reasons for why it helps Google; that is, we should be optimizing for Google—with Google’s diversity being a component of that.

Replace “tech” with “science fiction,” “men and women” with “black and white writers,” and “Google” with “Analog,” and you have a fairly accurate representation of Campbell’s position. He clearly saw his job as the optimization of science fiction. A diverse roster of writers, which would have resulted in far more interesting “analog simulations” of reality of the kind that he loved, would have gone a long way toward improving it. He didn’t make the effort, and the entire genre suffered as a result. Google, to its credit, seems to understand that diversity also offers competitive advantages when you aren’t just writing about the future, but inventing it. And anything else would be suboptimal.

A potent force of disintegration

As part of the production process these days, most nonfiction books from the major publishing houses get an automatic legal read—a review by a lawyer that is intended to check for anything potentially libelous about any living person. We can’t stop anyone from suing us, but we can make sure that we haven’t gone out of our way to invite it, and while most of the figures in Astounding have long since passed on, there are a handful who are still with us. As a result, I recently spent some time going over the relevant sections with a lawyer on the phone. The person on whom we ended up focusing the most, perhaps not surprisingly, was Harlan Ellison, who had a deserved reputation for being litigious, although he also liked to point out that he usually came out ahead. (After suing America Online for not promptly removing some of his stories that had been uploaded to a newsgroup on Usenet, Ellison explained in an interview that it was really about “slovenliness of thinking on the web” and the “slacker” philosophy that everything in life should be free: “If a professional gets published, well, any thief can steal it, and post it, and the thug feels abused if you whack him for it.” Ellison eventually received a settlement.) Mindful of this, we slowly went over the manuscript, checking each statement against its primary sources. Toward the end, the lawyer asked me if we had reasonable grounds for the sentence that described Ellison as “combative.” I replied: “Yes.”

Ellison died yesterday, and I never met or even corresponded with him, which is perhaps my greatest regret from the writing of Astounding. Two years ago, when I was just getting started, I wrote to him explaining the project and asking if I could interview him, but I never heard back. I don’t know if he ever saw the letter, and a mutual acquaintance told me that he was already too ill to respond to most of his mail. Ellison persists in the book as a kind of wraith in the background, appearing unexpectedly at various points in the narrative while trying to force his way into others. In an interview from the late seventies, he even claimed to have been in the room on the evening that L. Ron Hubbard came up with dianetics:

We were sitting around one night…who else was there? Alfred Bester, and Cyril Kornbluth, and Lester del Rey, and Ron Hubbard, who was making a penny a word, and had been for years…And somebody said, “Why don’t you invent a new religion? They’re always big.” We were clowning! You know, “Become Elmer Gantry! You’ll make a fortune!” He says, “I’m going to do it.” Sat down, stole a little bit from Freud, stole a little bit from Jung, a little bit from Adler…threw it all together, invented a few new words, because he was a science fiction writer, you know, “engrams” and “regression,” all that bullshit.

At the point at which this alleged event would have taken place, Ellison was a teenage kid living in Ohio. As another science fiction writer said to me: “Sometimes Harlan operates out of his own reality, which is always interesting but not necessarily identical to anybody else’s.”

Ellison may have never met Hubbard, but he interacted to one extent or another with the other subjects of my book, who often seemed bewildered by him—and I think it’s fair to say that he was the only science fiction writer of his generation who could plausibly seem like their match. He was very close to Asimov, while his relationship with Heinlein was cordial but distant, and John W. Campbell seems to viewed him mostly as an irritant. On April 15, 1958, Ellison, who was twenty-four, wrote in a letter to Campbell: “From the relatively—doubly—safe position of being eight hundred miles removed from your grasp and logic, and being fairly certain I’ll never sell to you anyhow, I wish to make a comment…lost in the wilderness.” After complaining about a story by Murray Leinster, which he described as a blatant example of “Campbell push-buttoning,” he continued:

Now writing to Campbell is not bad. It has been the policy of Astounding since I was in rompers, and anything that produces the kind of stuff ASF does, must have merit. But I look with sincere alarm at the ridiculous trend in the magazine currently: writing stories with the psi factor used when plotting or solving the problem becomes too wearying. Leinster has done it. Several others have done it also. I note this for your information. You may crucify me at will, Greeley.

Ellison, who was stationed at the time in Fort Knox, Kentucky, signed the letter “with respect and friendliness.” No response from Campbell survives.

Ellison had a point about the direction in which Campbell was taking the magazine, and he never had any reason to revise his opinion. Nearly a decade later, in the groundbreaking anthology Dangerous Visions, he mocked the editor’s circle of subservient writers and spoke of “John W. Campbell, Jr., who used to edit a magazine that ran science fiction, called Astounding, and who now edits a magazine that runs a lot of schematic drawings, called Analog.” He did sell one story to Campbell, “Brillo,” a collaboration with Ben Bova that was supposed to be sent using a pseudonym, but was accidentally submitted under both of their names. But the editor’s feelings about Ellison were never particularly warm. Campbell once wrote to a correspondent: “In my terms, Ellison seems more of the Hitler-Genghis Khan type genius—he’s destructive, rather than constructive. The language lacks an adequate term for this type of entity; he’s not a hero, but an antihero means something more on the order of a hopeless, helpless slob than a potent force of disintegration.” He wrote elsewhere that Ellison needed “a muzzle more than a platform,” and another letter includes the amazing—but not atypical—lines: “I don’t know whether it’s the hyper-defensive attitude of the undersize or what, but [Ellison’s] an insulting little squirt with a nasty tongue. He’s one of the type that earned the appellation ‘kike’; as Einstein, Disraeli, and thousands of others have demonstrated, it ain’t racial—it’s personal.” Ellison never saw these letters, and as I transcribed them for the book, I wondered what he would think. There’s no way of knowing now. But I suspect that he would have liked it.

A Hawk From a Handsaw, Part 1

Note: My article “The Campbell Machine,” which describes one of the strangest episodes in the history of Astounding Science Fiction, is now available online and in the July/August issue of Analog. To celebrate its publication, I’m republishing a series about an equally curious point of intersection between science fiction and the paranormal. This post originally appeared, in a slightly different form, on February 15, 2017.

I am but mad north-north-west. When the wind is southerly, I know a hawk from a handsaw.

—Hamlet

In the summer of 1974, the Israeli magician and purported psychic Uri Geller arrived at Birkbeck College in Bloomsbury, London, where the physicist David Bohm planned to subject him to a series of tests. Two of the appointed observers were the authors Arthur Koestler and Arthur C. Clarke, of whom Geller writes in his autobiography:

Arthur Clarke…would be particularly important because he was highly skeptical of anything paranormal. His position was that his books, like 2001 and Childhood’s End, were pure science fiction, and it would be highly unlikely that any of their fantasies would come true, at least in his own lifetime.

He met the group in a conference room, where Koestler was outwardly polite, even as Geller sensed that he “really wasn’t getting through to Arthur C. Clarke.” A demonstration seemed to be in order, so Geller asked Clarke to hold one of his own house keys in one hand, watching closely to make sure that it wasn’t switched, handled, or subjected to any trickery. Soon enough, the key began to bend. Clarke cried out, in what I like to think was an inadvertent echo of his most famous story: “My God, my eyes are seeing it! It’s bending!”

Geller went on to display his talents in a number of other ways, including forcing a Geiger counter to click at an accelerated rate merely by concentrating on it. (The skeptic James Randi has suggested that Geller had a magnet taped to his leg.) “By that time,” Geller writes, “Arthur Clarke seemed to have lost all his skepticism. He said something like, ‘My God! It’s all coming true! This is what I wrote about in Childhood’s End. I can’t believe it.'” Geller continues:

Clarke was not there just to scoff. He had wanted things to happen. He just wanted to be completely convinced that everything was legitimate. When he saw that it was, he told the others: “Look, the magicians and the journalists who are knocking this better put up or shut up now. Unless they can repeat the same things Geller is doing under the same rigidly controlled conditions, they have nothing further to say.”

Clarke also described the plot of Childhood’s End, which Geller evidently hadn’t read: “It involves a UFO that is hovering over the earth and controlling it. He had written the book about twenty years ago. He said that, after being a total skeptic about these things, his mind had really been changed by observing these experiments.”

It’s tempting to think that Geller is exaggerating the extent of the author’s astonishment, but here’s what Clarke himself said of it much later:

Although it’s hard to focus on that hectic and confusing day at Birkbeck College in 1974…I suspect that Uri Geller’s account in My Story is all too accurate…In view of the chaos at the hastily arranged Birkbeck encounter, the phrase “rigidly controlled conditions” is hilarious. But that last sentence is right on target, for [the reproduction of Geller’s effects by stage magicians] is precisely what happened…Nevertheless, I must confess a sneaking fondness for Uri; though he left a trail of bent cutlery and fractured reputations round the world, he provided much-needed entertainment at a troubled and unhappy time.

Geller has largely faded from the public consciousness, but Clarke—who continued to believe long afterward that paranormal phenomena “can’t all be nonsense”—wasn’t the only prominent science fiction writer to find him intriguing. Robert Anton Wilson, one of my intellectual heroes, discusses him at length in the book Cosmic Trigger, in which he recounts a strange incident that was experienced by his friend Saul-Paul Sirag. The year before the Birkbeck tests, Sirag allegedly saw Geller’s head turn into that of a “bird of prey,” like a hawk: “His nose became a beak, and his entire head sprouted feathers, down to his neck and shoulders.” (Wilson neglects to mention that Sirag was also taking LSD at the time.) The hawk, Sirag thought, was the form assumed by an alien intelligence that was supposedly in contact with Geller, and he didn’t know that it had appeared in the same shape to two other witnesses, including a psychic named Ray Stanford and another man who nicknamed it “Horus,” after the Egyptian god with a hawk’s head.

And it gets even weirder. A few months later, Sirag saw the January 1974 issue of Analog, which featured the story “The Horus Errand” by William E. Cochrane. The cover illustration depicted a man wearing a hawklike helmet, with the name “Stanford” written over his breast pocket. According to one of Sirag’s friends, the occultist Alan Vaughan, the character in the painting even looked a little like Ray Stanford, and you can judge the resemblance for yourself. Vaughan was interested enough to write to the artist, the legendary Frank Kelly Freas, for more information. (Freas, incidentally, was close friends with John W. Campbell, to the point where Campbell even asked him to serve as the guardian for his daughters if anything ever happened to him or his wife.) Freas replied that he had never met Stanford in person or knew how he looked, but that he had once received a psychic consultation from him by mail, in which Stanford told Freas that he had been “some sort of illustrator in a past life in ancient Egypt.” As a result, Freas began to consciously employ Egyptian imagery in his work, and the design of the helmet on the cover was entirely his own, without any reference to the story. At that point, the whole thing kind of peters out, aside from serving as an example of the kind of absurd coincidence that was so close to Wilson’s heart. But the intersection of Arthur C. Clarke, Uri Geller, and Robert Anton Wilson at that particular moment in time is a striking one, and it points toward an important thread in the history of science fiction that tends to be overlooked or ignored—perhaps because it’s often guarded by ominous hawks. I’ll be digging into this more deeply tomorrow.

Changing the future

Astounding: John W. Campbell, Isaac Asimov, Robert A. Heinlein, L. Ron Hubbard, and the Golden Age of Science Fiction is now scheduled to be released on October 23, 2018. It was originally slated for August 14, but my publisher recently raised the possibility of pushing it back, and we agreed on the new date earlier this week. Why the change? Well, it’s a good thing. This is a big book—by one estimate, we’re looking at close to five hundred pages, including endnotes, back matter, and index—and it needs time to be edited, typeset, and put into production. We could also use the extra nine weeks to get it into bookstores and into the hands of reviewers, and rescheduling it for the fall puts us in a better position. The one downside, at least from my point of view, is that now we’ll be coming out in a corridor that is always packed with major releases, and it’s going to be challenging for us to stand out. (It’s also just two weeks before the midterm elections, and I’m worried about how much bandwidth readers will have to think about anything else.) But everybody involved seems to think that we can handle it, and I have no reason to doubt their enthusiasm or expertise.

In short, if you’ve been looking forward to reading Astounding, you’ll have to wait two months longer. (Apart from an upcoming round of minor edits, by the way, the book is basically finished.) In the meantime, at the end of this month, I’m attending the academic conference “Grappling With the Futures” at Harvard and Boston University, where I’ll be delivering a presentation on the evolution of psychohistory alongside the scholar Emmanuelle Burton. The July/August issue of Analog will feature “The Campbell Machine,” a modified excerpt from the book, including a lot of material that won’t appear anywhere else, about one of the most significant incidents in John W. Campbell’s life—the tragic death of his stepson, which encouraged his interest in psionics and culminated in his support of the Hieronymus Machine. And I’m hopeful that a piece about Campbell’s role in the development of dianetics will appear elsewhere in the fall. I’ve also confirmed that I’ll be a program participant at the upcoming World Science Fiction Convention in San Jose, which runs from August 16 to 20. At one point, I’d planned to have the book in stores by then, which isn’t quite how it worked out. But if you run into me there, ask me for a copy. If I have one handy, it’s yours.

The dawn of man

Note: To celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the release of 2001: A Space Odyssey, which held its premiere on April 2, 1968, I’ll be spending the week looking at various aspects of what remains the greatest science fiction movie ever made.

Almost from the moment that critics began to write about 2001, it became fashionable to observe that the best performance in the movie was by an actor playing a computer. In his review in Analog, for example, P. Schuyler Miller wrote:

The actors, except for the gentle voice of HAL, are thoroughly wooden and uninteresting, and I can’t help wondering whether this isn’t Kubrick’s subtle way of suggesting that the computer is really more “human” than they and fully justified in trying to get rid of them before they louse up an important mission. Someday we may know whether the theme of this part is a Clarke or a Kubrick contribution. I suspect it was the latter…perhaps just because Stanley Kubrick is said to like gadgets.

This criticism is often used to denigrate the other performances or the film’s supposed lack of humanity, but I prefer to take it as a tribute to the work of actor Douglas Rain, Kubrick and Clarke’s script, and the brilliant design of HAL himself. The fact that a computer is the character we remember best isn’t a flaw in the movie, but a testament to its skill and imagination. And as I’ve noted elsewhere, the acting is excellent—it’s just so understated and naturalistic that it seems vaguely incongruous in such spectacular settings. (Compare it to the performances in Destination Moon, for instance, and you see how good Keir Dullea and William Sylvester really are here.)

But I also think that the best performance in 2001 isn’t by Douglas Rain at all, but by Vivian Kubrick, in her short appearance on the phone as Heywood Floyd’s daughter. It’s a curious scene that breaks many of the rules of good storytelling—it doesn’t lead anywhere, it’s evidently designed to do nothing but show off a piece of hardware, and it peters out even as we watch it. The funniest line in the movie may be Floyd’s important message:

Listen, sweetheart, I want you to tell mommy something for me. Will you remember? Well, tell mommy that I telephoned. Okay? And that I’ll try to telephone tomorrow. Now will you tell her that?

But that’s oddly true to life as well. And when I watch the scene today, with a five-year-old daughter of my own, it seems to me that there’s no more realistic little girl in all of movies. (Kubrick shot the scene himself, asking the questions from offscreen, and there’s a revealing moment when the camera rises to stay with Vivian as she stands. This is sometimes singled out as a goof, although there’s no reason why a sufficiently sophisticated video phone wouldn’t be able to track her automatically.) It’s a scene that few other films would have even thought to include, and now that video chat is something that we all take for granted, we can see through the screen to the touchingly sweet girl on the other side. On some level, Kubrick simply wanted his daughter to be in the movie, and you can’t blame him.

At the time, 2001 was criticized as a soulless hunk of technology, but now it seems deeply human, at least compared to many of its imitators. Yesterday in the New York Times, Bruce Handy shared a story from Keir Dullea, who explained why he breaks the glass in the hotel room at the end, just before he comes face to face with himself as an old man:

Originally, Stanley’s concept for the scene was that I’d just be eating and hear something and get up. But I said, “Stanley, let me find some slightly different way that’s kind of an action where I’m reaching—let me knock the glass off, and then in mid-gesture, when I’m bending over to pick it up, let me hear the breathing from that bent-over position.” That’s all. And he says, “Oh, fine. That sounds good.” I just wanted to find a different way to play the scene than blankly hearing something. I just thought it was more interesting.

I love this anecdote, not just because it’s an example of an evocative moment that arose from an actor’s pragmatic considerations, but because it feels like an emblem of the production of the movie as a whole. 2001 remains the most technically ambitious movie of all time, but it was also a project in which countless issues were being figured out on the fly. Every solution was a response to a specific problem, and it covered a dizzying range of challenges—from the makeup for the apes to the air hostess walking upside down—that might have come from different movies entirely.

2001, in short, was made by hand—and it’s revealing that many viewers assume that computers had to be involved, when they didn’t figure in the process at all. (All of the “digital” readouts on the spacecraft, for instance, were individually animated, shot on separate reels of film, and projected onto those tiny screens on set, which staggers me even to think about it. And even after all these years, I still can’t get my head around the techniques behind the Star Gate sequence.) It reminds me, in fact, of another movie that happens to be celebrating an anniversary this year. As a recent video essay pointed out, if the visual effects in Jurassic Park have held up so well, it’s because most of them aren’t digital at all. The majority consist of a combination of practical effects, stop motion, animatronics, raptor costumes, and a healthy amount of misdirection, with computers used only when absolutely necessary. Each solution is targeted at the specific problems presented by a snippet of film that might last just for a few seconds, and it moves so freely from one trick to another that we rarely have a chance to see through it. It’s here, not in A.I., that Spielberg got closest to Kubrick, and it hints at something important about the movies that push the technical aspects of the medium. They’re often criticized for an absence of humanity, but in retrospect, they seem achingly human, if only because of the total engagement and attention that was required for every frame. Most of their successors lack the same imaginative intensity, which is a greater culprit than the use of digital tools themselves. Today, computers are used to create effects that are perfect, but immediately forgettable. And one of the wonderful ironies of 2001 is that it used nothing but practical effects to create a computer that no viewer can ever forget.

Exploring “The Proving Ground,” Part 3

Note: My novella “The Proving Ground,” which was first published in the January/February 2017 issue of Analog, is being reprinted this month in Lightspeed Magazine. It will also be appearing in the upcoming edition of The Year’s Best Science Fiction, edited by Gardner Dozois, and is a finalist for the Analytical Laboratory award for Best Novella. This post on the story’s conception and writing originally appeared, in a slightly different form, on January 11, 2017.

In the famous book-length interview Hitchcock/Truffaut, the director François Truffaut observes of The Birds: “This happens to be one picture, I think, in which the public doesn’t try to anticipate. They merely suspect that the attacks by the birds are going to become increasingly serious. The first part is an entirely normal picture with psychological overtones, and it is only at the end of each scene that some clue hints at the potential menace of the birds.” And Alfred Hitchcock’s response is very revealing:

I had to do it that way because the public’s curiosity was bound to be aroused by the articles in the press and the reviews, as well as by the word-of-mouth talk about the picture. I didn’t want the public to become too impatient about the birds, because that would distract them from the personal story of the two central characters. Those references at the end of each scene were my way of saying, “Just be patient. They’re coming soon.”

Hitchcock continues: “This is why we have an isolated attack on Melanie by a sea gull, why I was careful to put a dead bird outside the schoolteacher’s house at night, and also why we put the birds on the wires when the girl drives away from the house in the evening. All of this was my way of saying to the audience, ‘Don’t worry, they’re coming. The birds are on their way!’”

I kept this advice constantly in mind while plotting “The Proving Ground,” which is the closest that I’ve come to an outright homage to another work of art. (My novelette “Inversus” contains many references to Through the Looking-Glass, but the plot doesn’t have anything in common with the book, and the parallels between “The Whale God” and George Orwell’s essay “Shooting an Elephant” didn’t emerge until that story was almost finished.) I knew that I had to quote from the movie directly, if only to acknowledge my sources and make it clear that I wasn’t trying to put anything over on the reader, which is also why I open it with an epigraph from Daphne du Maurier’s original short story. When I tried to figure out where to put those references, however, I realized that it wasn’t just a matter of paying tribute to my inspiration, but of drawing upon the very useful solutions that Hitchcock and screenwriter Evan Hunter had developed for the same set of problems. Any story about a series of bird attacks is going to confront similar challenges. You have to build up to it slowly, saving the most exciting moments for the second half, which leaves you with the tricky question of what to do in the meantime. Hitchcock and Hunter had clearly thought about this carefully, and by laying in analogous beats at approximately the same points, I was able to benefit from the structure that they had already discovered. “The Proving Ground” follows The Birds overtly in only a handful of places—the first attack on Haley, the sight of the birds perching on the trellises of the wind tower, the noiseless attack in the supply shed, the mass assault on the seastead, and Haley inching through the silent ranks of birds at the end. But they all occur at moments that play a specific role in the story.

The result taught me a lot about the nature of homage. I was well aware that “The Proving Ground” wasn’t the first attempt to draw on The Birds to deliver an environmental message, and I even thought about including an explicit reference to Birdemic, which is one of my favorite bad movies. If there’s a difference between the two, and I hope that there is, it’s that I ended up at The Birds in a roundabout fashion, after realizing that it lent itself nicely to the setting and themes at which I had independently arrived. At that point, I had already filled out much of the background, so I was able to use Hitchcock’s movie as a kind of organizing principle to keep this unwieldy mass of material under control. It wasn’t until I actually sat down and started to write it that I realized how big it was going to be: it became a novella, although just barely, and the longest thing I’d ever published in Analog. This was partially due to the fact that the background had to be unusually detailed, and the story would only make sense if I devoted sufficient space to the geography of the Marshall Islands, its environmental situation, and the physical layout of the seastead. I also had to sketch in the political situation and provide some historical context, not just because it was interesting in itself, but because it clarified the logic behind the protagonist’s actions—the Marshallese have had to deal with the problem of reparations before, and Haley is very mindful of this. This meant adding several thousand words to a story that might have played just as well as a novelette, at least from the point of view of pure action, and I found that the structure I borrowed from Hitchcock allowed it to read as a unified whole, rather than as a collection of disparate ideas united only by the setting.

This became particularly helpful after the circle of associations expanded yet again, to encompass the history of the atomic bomb tests that the United States government conducted at Bikini Atoll. I hadn’t planned to set the story on Bikini itself, but it eventually became clear that it was the obvious setting, simply from the point of view of the logistics of the seastead. An atoll provides a natural breakwater against waves—Bikini is even mentioned by name in the relevant section in Patri Friedman’s book on seasteading—and the location had other advantages: it was uninhabited but livable, with plenty of infrastructure and equipment left behind from the nuclear tests. Placing the seastead there added another level of resonance to the story, and instead of trying to reconcile the different elements, I ended up placing the components from The Birds side by side with the material about Bikini, just to see what happened. As it turned out, the two halves complemented each other in surprising ways, and I didn’t need to tease out the connections. “The Proving Ground,” as the title implies, is about a proof of concept: the Marshall Islands were chosen for Operation Crossroads because they were remote and politically vulnerable, and they end up as a test case for the seastead for similar reasons. Haley tries to use the lessons of the first incident to guide her response to the second, but the birds have other plans. In both du Maurier and Hitchcock, the attacks are left unexplained, while in this story, they’re an unanticipated side effect of a technological solution to a social and ecological problem. Any attempt at an explanation would have ruined the earlier versions, but I think it’s necessary here. The birds are an accidental but inevitable consequence of a plan that initially failed to take them into account. And that’s how they ended up in this story, too.

Exploring “The Proving Ground,” Part 1

Note: My novella “The Proving Ground,” which was first published in the January/February 2017 issue of Analog, is being reprinted this month in Lightspeed Magazine. It will also be appearing in the upcoming edition of The Year’s Best Science Fiction, edited by Gardner Dozois, and is a finalist for the Analytical Laboratory award for Best Novella. This post on the story’s conception and writing originally appeared, in a slightly different form, on January 9, 2017.

Usually, whenever I start working on a story, I try to begin with as few preconceptions about it as possible. Years ago, in a post called “The Anthropic Principle of Fiction,” I made the argument that the biggest, most obvious elements of the narrative—the setting, the characters, the theme—should be among the last things that the writer figures out, and that the overall components should all be chosen with an eye to enabling a pivotal revelation toward the end. This isn’t true of all plots, of course, but for the sort of scientific puzzle stories in which I’ve come to specialize, it’s all but essential. Mystery writers grasp this intuitively, but it can be harder to accept in science fiction, perhaps because we’ve been trained to think in terms of worldbuilding from an initial premise, rather than reasoning backward from the final result. But both are equally legitimate approaches, if followed with sufficient logic and imagination. As I wrote in my first treatment of the subject:

Readers will happily accept almost any premise when it’s introduced in the first few pages, but as the story continues, they’ll grow increasingly skeptical of any plot element that doesn’t seem to follow from that initial set of rules—so you’d better make sure that the world in which the story takes place has been fine-tuned to allow whatever implausibilities you later decide to include.

Which led me to formulate a general rule: The largest elements of the story should be determined by its least plausible details.

I still believe this. For “The Proving Ground,” however, I broke that rule, along with an even more important one: it’s the first and only story that I’ve ever written around an explicit political theme. Any discussion of this novella, then, has to begin with the disclaimer that I don’t recommend writing this way—and if the result works at all, it’s because of good luck and more work than I ever hope to invest in a short story again. (I write most of my stories in about two weeks, but “The Proving Ground” took twice that long.) Fortunately, it came out of a confluence of factors that seem unlikely to repeat themselves. A friend of mine was hoping to write a series of freelance editorials about climate change, and she asked me to come on board as a kind of unofficial consultant. She began by giving me a reading list, and I spent about a month working my way through such books as The Sixth Extinction by Elizabeth Kolbert, This Changes Everything by Naomi Klein, Windfall by McKenzie Funk, and Don’t Even Think About It by George Marshall. Ultimately, we didn’t end up working together, mostly because we each got distracted by other projects. But it allowed me to think at length about what I still believe is the central issue of our time, and even though I didn’t come away with any clear answers, it provided me with plenty of story material. Climate change has been a favorite subject of science fiction for decades, but the result tends to take place after sea levels have already risen, and I wanted to write something that was in my wheelhouse—a story set in the present or near future that tackled the theme using the tools of suspense.

I ended up focusing on an idea that I first encountered in Funk’s Windfall. The Marshall Islands are among the countries that are the most threatened by global warming, as well as one of the most likely beneficiaries of climate-change reparations from more developed nations. In order to qualify for reparations, however, they have to fulfill the legal definition of a country, which means that they need to have land—when it’s precisely for the loss of that land that they hope to be compensated. It’s easy to imagine them caught in a regulatory twilight zone, with rising sea levels erasing their territory, while also depriving them of the sovereign status from which they could initiate proceedings in the international court system. Funk does a nice job of laying out the dilemma, and it could lead to any number of stories. A different writer, for instance, might have taken it as the basis for a dark, bitter satire. That isn’t a mode in which I’m comfortable operating, though, and I was more intrigued by another detail, which is that one of the proposed solutions to the territorial problem is a seastead, or an artificial island that would allow the Marshallese to maintain their claim to statehood. This struck me as a good backdrop for whatever story I ended up writing, and although I could have started it at a point in which a seastead had already been built, it seemed more promising to begin when it was still under construction. Science fiction is often structured around a major engineering project, both because it allows for future technology to be described in a fairly organic way and because it can be used to create the interim objectives and crises that a story needs to keep moving. (It also provides a convenient stage on which the competent man—or woman—can shine.)

I decided, then, that this was going to be a story about the construction of a seastead in the Marshall Islands, which was pretty specific. There was also plenty of available but obscure background material, ranging from general treatments of the idea in books like The Millennial Project by Marshall T. Savage—which had been sitting unread on my shelf for years—to detailed proposals for seasteads in the real world. (The obvious example is The Seasteading Institute, a libertarian pipe dream funded by Peter Thiel, who has since gone on to even more dubious ventures. But it generated a lot of useful proposals and plans along the way, as long as you treat it as the legwork for a science fiction story, rather than as a project on which you’re hoping to get someone to actually spend fifty billion dollars.) As I continued to read, however, I became uncomfortably aware that I had broken my one rule. Instead of working backward from a climax, I was moving forward from a setting, on the assumption that I’d find something in my research that I could turn into a proper story. It isn’t impossible, but it also isn’t an approach that I’d recommend: not only does it double the investment of time required, but it increases the chances that you’ll distort the facts to fit them into the framework that you’ve imposed on yourself. In this instance, I think I pulled it off, but there’s no guarantee that I will again. “The Proving Ground” took a lot of wrong turns, and it was only through sheer good fortune that I was able to find a story that I felt able to write. Tomorrow, I’ll talk more about how I nearly followed one potential premise into a dead end, and how I found myself writing the story, to my surprise, as an homage to Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds.

Looking for “The Spires”

Over two years ago, I was browsing at my local thrift store when my eye was caught by a book titled Alaska Bush Pilots in the Float Country. Its dust jacket read: “The men who brought airplanes to Alaska’s Panhandle were a different breed: a little braver than the average pilot and blessed with the particular skills and set of nerves it requires to fly float planes, those Lockheed Vegas made of plywood that were held together by termites holding hands, as well as the sturdy Fairchild 71s and Bellanca Pacemakers.” This might not seem like a volume that would appeal to the average reader, but I bought it—and I had a particular use for it in mind. Like most writers, I’m constantly on the lookout for promising veins of material, and my inner spidey sense began to tingle as soon as I saw that cover. If I had to describe the kind of short stories that I like to write, I’d call them carefully plotted works of science fiction, usually staged against a colorful backdrop, often with elements of horror. The Alaskan Panhandle in the thirties seemed like as good a setting for this as any, and that book on bush pilots was visibly packed with more information than I would need for a novelette. I’ve come to treasure works of nonfiction that provide a narrow but deep slice of knowledge about a previously unexplored topic, and I automatically got to thinking about bush pilots in Alaska, even though the subject had never interested me before.

It took me over a year to get to it, but the result was my novelette “The Spires,” which appears in the current issue of Analog Science Fiction and Fact. It was the first story that I’d attempted since commencing work on Astounding, and it was more informed than usual by the history of science fiction. When I sat down to think about it in earnest, I decided more or less at random to approach it as a tribute to the work of Charles Fort, who filled four large books with accounts of unexplained events that he gleaned from the newspaper archives at the New York Public Library. In New Lands, Fort mentions a phantom city that has occasionally been seen in the sky over Alaska, which seemed like an excellent place to start. My goal, as usual, was to begin with what sounded like a paranormal phenomenon and work backward to a scientific explanation that wouldn’t be out of place in Analog, sort of like The X-Files in reverse. I’m still not entirely sure what to think of the result here—and I resisted it for a long time. It comes perilously close to a shaggy dog story, but I like the atmosphere, and the “solution,” while not one that I would have chosen under most circumstances, ended up feeling inevitable. If you read it, I hope you’ll agree. In a few weeks, I’ll talk about its origins at length, but in the meantime, I’ll leave you with one of my favorite quotes from Fort: “My own notion is that it is very unsportsmanlike ever to mention fraud. Accept anything. Then explain it your way.”

The cosmic engineers

On May 18, 1966, the novelist C.P. Snow delivered a talk titled “The Status of Doctors” before the Royal Society of Medicine in London. Snow—who had studied physics and chemistry at the University of Leicester and Cambridge—spent much of his speech comparing the fields of engineering and medicine, noting that doctors enjoyed a more exalted social status than engineers, perhaps because their work was easier to understand: “Doctors have a higher place in the popular imagination and I think also in the more esoteric imagination. A novelist can bring a doctor into a novel without any trouble at all, people know who he is; but try bringing an engineer into a novel and it is terribly difficult—they have not got recognition symbols in the way the medical profession has.” He continued:

I do not think doctors suffer from the other great weakness of engineers, that is, their complete lack of verbalism. Engineers can often be extremely clever but they cannot spell and they cannot speak. The doctors I have known are extremely articulate. I suspect the descriptive processes they have to go through, both themselves and presumably with their patients, are extremely good verbal training, and I do not think it is an accident that the one thing the medical profession has done, apart from producing doctors, is to produce writers. I do not think it is an accident that there are almost no engineering writers, and very few from the scientific professions. On the other hand, the medical profession has produced some really good writers in the last hundred years.

Snow would presumably have been mortified by the idea of a magazine that published nothing but stories written by and for engineers, but by the time that he gave his talk, Astounding Science Fiction—which had changed its name several years earlier to Analog—had been in that business for decades. In practice, science fiction writers came from a wide range of professional backgrounds, but there was no doubt that John W. Campbell’s ideal author was a working engineer who wrote for his own pleasure on the side. In an editorial in the February 1941 issue, the editor delivered a pitch to them directly:

Most of Astounding’s authors are, in the professional sense, amateur authors, spare-time writers who earn their bread and butter in one field of work, and use their writing ability as a source of the jam supply…”Jam” in the above sense is useful. Briefly, it amounts to the equivalent of a couple of new suits, or a suit and overcoat, for a short story, a new radio with, say, FM tuning for a novelette, and a new car or so for a novel.

He also made no secret of what kind of professional he was hoping to find. By the end of the decade, a survey indicated that fully fifteen percent of the magazine’s readers were engineers themselves. As Damon Knight wrote in In Search of Wonder: “[Campbell] deliberately built up a readership among practicing scientists and technicians.” And he expected to source most of his writers directly from that existing audience.

But his reasons for looking for engineers were more complicated than they might seem. When Campbell took over Astounding in 1937, the submissions that he received tended to fall into one of two categories. Some were from professional pulp writers who wrote for multiple genres; others were written by younger fans who had grown up with science fiction, loved it, and desperately wanted to break into the magazine. Neither was the kind of writer whom Campbell secretly wanted. Working authors had to write quickly to make a living at a penny a word, and they were usually content to stick to the tricks and formulas that they knew best. They certainly weren’t interested in repeated revisions, which meant that they weren’t likely to be receptive to the notes that Campbell was planning to give. (Some writers, like Edmond Hamilton, bowed out entirely because they didn’t feel like changing.) The fans were even worse. They had only emerged as a force in their own right within the last few years, and you couldn’t tell them anything—they treated science fiction as their personal property, which made it hard to give them any feedback. What Campbell wanted was a legion of successful engineers who wrote science fiction because they liked it, didn’t take it so personally that they would push back against his suggestions, and had the time and leisure to rework a story to his specifications. These men were understandably hard to find, and few of the major writers of the golden age fit that profile completely. It wasn’t until after the war that the figure of the engineer who wrote science fiction as a hobby really began to emerge.

By 1967, a year after C.P. Snow delivered his talk, however, it was possible for Harlan Ellison to refer in the anthology Dangerous Visions to “John W. Campbell, Jr., who used to edit a magazine that ran science fiction, called Astounding, and who now edits a magazine that runs a lot of schematic drawings, called Analog.” And there’s little doubt that it was exactly the magazine that Campbell wanted. His control over it was even more complete than it had been in the thirties and forties, largely because of the type of writer he had selected for it, as Damon Knight pointed out: “He deliberately cultivated technically oriented writers with marginal writing skills…Campbell was building a new stable he knew he could keep.” And this side of his legacy persists even today. In Psychoanalysis: The Impossible Profession, Janet Malcolm writes:

Soon after the Big Bang of Freud’s major discoveries…the historian of psychoanalysis notes a fork in the road. One path leads outward into the general culture, widening to become the grand boulevard of psychoanalytic influence…The other is the narrow, inward-turning path of psychoanalytic therapy: a hidden, almost secret byway travelled by few.

Replace “Freud” with “Campbell” and “psychoanalysis” with “science fiction,” and you have a decent picture of what happened with Analog. Science fiction took over the world, while Campbell’s old magazine continued to pursue his private vision, and its writers fit that profile now more than ever. It’s no longer possible to write short fiction for a living, which makes it very attractive for engineers who write on the side. I love Analog—it changed my life. But if you ever wonder why it looks so different from even the rest of the genre, it’s because it was engineered that way.

Sci-Fi and Si

In 1959, the newspaper magnate Samuel I. Newhouse allegedly asked his wife Mitzi what she wanted for their upcoming wedding anniversary. When she told him that she wanted Vogue, he bought all of Condé Nast. At the time, the publishing firm was already in negotiations to acquire the titles of the aging Street & Smith, and Newhouse, its new owner, inherited this transaction. Here’s how Carol Felsenthal describes the deal in Citizen Newhouse:

For $4 million [Newhouse] bought Charm, Living for Young Homemakers, and Mademoiselle. (Also included were five sports annuals, which he ignored, allowing them to continue to operate with a minimal staff and low-overhead offices—separate from Condé Nast’s—and to earn a small but steady profit.) He ordered that Charm be folded into Glamour. Living for Young Homemakers become House & Garden Guides. Mademoiselle was allowed to survive because its audience was younger and better educated than Glamour’s; Mademoiselle was aimed at the college girl, Glamour at the secretary.

Newhouse’s eldest son, who was known as Si, joined Glamour at the age of thirty-five, and within a few years, he was promoted to oversee all the company’s magazines. When he passed away yesterday, as his obituary in the Times notes, he was a media titan “who as the owner of The New Yorker, Vogue, Vanity Fair, Architectural Digest and other magazines wielded vast influence over American culture, fashion and social taste.”

What this obituary—and all the other biographies that I’ve seen—fails to mention is that when the Newhouses acquired Street & Smith, they also bought Astounding Science Fiction. In the context of two remarkably busy lives, this merits little more than a footnote, but it was a significant event in the career of John W. Campbell and, by extension, the genre as a whole. In practice, Campbell was unaffected by the change in ownership, and he joked that he employed Condé Nast to get his ideas out, rather than the other way around. (Its most visible impact was a brief experiment with a larger format, allowing the magazine to sell ads to technical advertisers that didn’t make smaller printing plates, but the timing was lousy, and it was discontinued after two years.) But it also seems to have filled him with a sense of legitimacy. Campbell, like his father, had an uncritical admiration for businessmen—capitalism was the one orthodoxy that he took at face value—and from his new office in the Graybar Building on Lexington Avenue, he continued to identify with his corporate superiors. When Isaac Asimov tried to pick up a check at lunch, Campbell pinned his hand to the table: “Never argue with a giant corporation, Isaac.” And when a fan told him that he had written a story, but wasn’t sure whether it was right for the magazine, Campbell drew himself up: “And since when does the Condé Nast Publications, Incorporated pay you to make editorial decisions?” In fact, the change in ownership seems to have freed him up to make the title change that he had been contemplating for years. Shortly after the sale, Astounding became Analog, much to the chagrin of longtime fans.

Some readers discerned more sinister forces at work. In the memorial essay collection John W. Campbell: An Australian Tribute, the prominent fan Redd Boggs wrote: “What indulgent publisher is this who puts out and puts up with Campbell’s personal little journal, his fanzine?…One was astounded to see the magazine plunge along as hardily as ever after Condé Nast and Samuel I. Newhouse swallowed up and digested Street & Smith.” He went on to answer his own question:

We are making a mistake when we think of Analog as a science fiction magazine and of John W. Campbell as an editor. The financial backer or backers of Analog obviously do not think that way. They regard Analog first and foremost as a propaganda mill for the right wing, and Campbell as a propagandist of formidable puissance and persuasiveness. The stories, aside from those which echo Campbell’s own ideas, are only incidental to the magazine, the bait that lures the suckers. Analog’s raison d’être is Campbell’s editorials. If Campbell died, retired, or backslid into rationality, the magazine would fold instantly…

Campbell is a precious commodity indeed, a clever and indefatigable propagandist for the right wing, much superior in intelligence and persuasive powers to, say, William F. Buckley, and he works for bargain basement prices at that. And if our masters are as smart as I think they are…I feel sure that they would know how to cherish such heaven-sent gifts, even as I would.

This is an ingenious argument, and I almost want to believe it, if only because it makes science fiction seem as important as it likes to see itself. In reality, it seems likely that Si Newhouse barely thought about Analog at all, which isn’t to say that he wasn’t aware of it. His Times obituary notes: “He claimed to read every one of his magazines—they numbered more than fifteen—from cover to cover.” This conjures up the interesting image of Newhouse reading the first installment of Dune and the latest update on the Dean Drive, although it’s hard to imagine that he cared. Campbell—who must have existed as a wraith in the peripheral vision of Diana Vreeland of Vogue, who worked in the same building for nearly a decade—was allowed to run the magazine on his own, and it was tolerated as along as it remained modestly profitable. Newhouse’s own interests ran less to science fiction than toward what David Remnick describes as “gangster pictures, romantic comedies, film noir, silent comedies, the avant-garde.” (He did acquire Wired, but his most profound impact on our future was one that nobody could have anticipated—it was his idea to publish Donald Trump’s The Art of the Deal.) When you love science fiction, it can seem like nothing else matters, but it hardly registers in the life of someone like Newhouse. We don’t know what Campbell thought of him, but I suspect that he wished that they had been closer. Campbell wanted nothing more than to bring his notions, like psionics, to a wider audience, and he spent the last decade of his career with a publishing magnate within view but tantalizingly out of reach—and his name was even “Psi.”

Optimizing the future

On Saturday, an online firestorm erupted over a ten-page memo written by James Damore, a twenty-eight-year-old software engineer at Google. Titled “Google’s Ideological Echo Chamber,” it led to its author being fired a few days later, and the furor is far from over—I have the uncomfortable feeling that it’s just getting started. (Damore has said that he intends to sue, and his case has already become a cause célèbre in exactly the circles that you’d expect.) In his memo, Damore essentially argues that the acknowledged gender gap in management and engineering roles at tech firms isn’t due to bias, but to “the distribution of preferences and abilities of men and women in part due to biological causes.” In women, these differences include “openness directed towards feelings and aesthetics rather than ideas,” “extraversion expressed as gregariousness rather than assertiveness,” “higher agreeableness,” and “neuroticism,” while men have a “higher drive for status” that leads them to take positions demanding “long, stressful hours that may not be worth it if you want a balanced and fulfilling life.” He summarizes:

I’m not saying that all men differ from women in the following ways or that these differences are “just.” I’m simply stating that the distribution of preferences and abilities of men and women differ in part due to biological causes and that these differences may explain why we don’t see equal representation of women in tech and leadership. Many of these differences are small and there’s significant overlap between men and women, so you can’t say anything about an individual given these population level distributions.

Damore quotes a decade-old research paper, which I suspect that he first encountered through the libertarian site Quillette, stating that as “society becomes more prosperous and more egalitarian, innate dispositional differences between men and women have more space to develop and the gap that exists between men and women in their personality becomes wider.” And he concludes: “We need to stop assuming that gender gaps imply sexism.”

I wasn’t even going to write about this here, but it rang a bell. Back in 1968, a science fiction fan named Ron Stoloff attended the World Science Fiction Convention in Berkeley, where he was disturbed both by the lack of diversity and by the presence of at least one fan costumed as Lt. Uhura in blackface. He wrote up his thoughts in an essay titled “The Negro and Science Fiction,” which was published the following year in the fanzine The Vorpal Sword. (I haven’t been able to track down the full issue, but you can find the first page of his article here.) On May 1, 1969, the editor John W. Campbell wrote Stoloff a long letter objecting to the argument and to the way that he had been characterized. It’s a fascinating document that I wish I could quote in full, but the most revealing section comes after Campbell asks rhetorically: “Look guy—do some thinking about this. How many Negro authors are there in science fiction?” He then answers his own question:

Now consider what effect a biased, anti-Negro editor could have on that. Manuscripts come in by mail from all over the world…I haven’t the foggiest notion what most of the authors look like—and I never yet heard of an editor who demanded a photograph of an author before he’d print his work! Nor demanded a notarized document proving he was write.

If Negro authors are extremely few—it’s solely because extremely few Negroes both wish to, and can, write in open competition. There isn’t any possible field of endeavor where race, religion, and sex make less difference. If there aren’t any individuals of a particular group in the authors’ column—it’s because either they didn’t want to, or weren’t able to. It’s got to be unbiased by the very nature of the process of submission.

Campbell’s argument is fundamentally the same as Damore’s. It states that the lack of black writers in the pages of Analog, like the underrepresentation of women in engineering roles at Google, isn’t due to bias, but because “either they didn’t want to, or weren’t able to.” (Campbell, like Damore, makes a point of insisting elsewhere that he’s speaking of the statistical description of the group as a whole, not of individuals, which strikes him as a meaningful distinction.) Earlier in the letter, however, Campbell inadvertently suggests another explanation for why “Negro authors are extremely few,” and it doesn’t have anything to do with ability:

Think about it a bit, and you’ll realize why there is so little mention of blacks in science fiction; we see no reason to go saying “Lookee lookee lookee! We’re using blacks in our stories! See the Black Man! See him in a spaceship!”

It is my strongly held opinion that any Black should be thrown out of any story, spaceship, or any other place—unless he’s a black man. That he’s got no business there just because he’s black, but every right there if he’s a man. (And the masculine embraces the feminine; Lt. Uhura is portrayed as no clinging vine, and not given to the whimper, whinny, and whine type behavior. She earned her place by competence—not by having a black skin.)

There are two implications here. The first is that all protagonists should be white males by default, a stance that Campbell might not even have seen as problematic—and it’s worth noting that even if race wasn’t made explicit in the story, the magazine’s illustrations overwhelmingly depicted its characters as white. There’s also the clear sense that black heroes have to “earn” their presence in the magazine, which, given the hundreds of cardboard “competent men” that Campbell cheerfully featured over the years, is laughable in itself. In fiction, as in life, if you’re black, you’ve evidently got to be twice as good to justify yourself.

It never seems to have occurred to Campbell that the dearth of minority writers in the genre might have been caused by a lack of characters who looked like them, as well as by similar issues in the fandom, and he never believed that he had the ability or the obligation to address the situation as an editor. (Elsewhere in the same letter, he writes: “What I am against—and what has been misinterpreted by a number of people—is the idea that any member of any group has any right to preferential treatment because he is a member.”) Left to itself, the scarcity of minority voices and characters was a self-perpetuating cycle that made it easy to argue that interest and ability were to blame. The hard part about encouraging diversity in science fiction, or anywhere else, is that it doesn’t happen by accident. It requires systematic, conscious effort, and the payoff might not be visible for years. That’s as hard and apparently unrewarding for a magazine that worries mostly about managing its inventory from one month to the next as it is for a technology company focused on yearly or quarterly returns. If Campbell had really wanted to see more black writers in Analog in the late sixties, he should have put more black characters in the magazine in the early forties. You could excuse this by saying that he had different objectives, and that it’s unfair to judge him in retrospect, but it’s equally true that it was a choice that he could have made, but didn’t. And science fiction was the poorer for it. In his memo, Damore writes:

Philosophically, I don’t think we should do arbitrary social engineering of tech just to make it appealing to equal portions of both men and women. For each of these changes, we need principled reasons for why it helps Google; that is, we should be optimizing for Google—with Google’s diversity being a component of that.

Replace “tech” with “science fiction,” “men and women” with “black and white writers,” and “Google” with “Analog,” and you have a fairly accurate representation of Campbell’s position. He clearly saw his job as the optimization of science fiction. A diverse roster of writers, which would have resulted in far more interesting “analog simulations” of reality of the kind that he loved, would have gone a long way toward improving it. He didn’t make the effort, and the entire genre suffered as a result. Google, to its credit, seems to understand that diversity also offers competitive advantages when you aren’t just writing about the future, but inventing it. And anything else would be suboptimal.

Children of the Lens

During World War II, as the use of radar became widespread in battle, the U.S. Navy introduced the Combat Information Center, a shipboard tactical room with maps, consoles, and screens of the kind that we’ve all seen in television and the movies. At the time, though, it was like something out of science fiction, and in fact, back in 1939, E.E. “Doc” Smith had described a very similar display in the serial Gray Lensman:

Red lights are fleets already in motion…Greens are fleets still at their bases. Ambers are the planets the greens took off from…The white star is us, the Directrix. That violet cross way over there is Jalte’s planet, our first objective. The pink comets are our free planets, their tails showing their intrinsic velocities.

After the war, in a letter dated June 11, 1947, the editor John W. Campbell told Smith that the similarity was more than just a coincidence. Claiming to have been approached “unofficially, and in confidence” by a naval officer who played an important role in developing the C.I.C., Campbell said:

The entire setup was taken specifically, directly, and consciously from the Directrix. In your story, you reached the situation the Navy was in—more communications channels than integration techniques to handle it. You proposed such an integrating technique, and proved how advantageous it could be…Sitting in Michigan, some years before Pearl Harbor, you played a large share in the greatest and most decisive naval action of the recent war!

Unfortunately, this wasn’t true. The naval officer in question, Cal Laning, was indeed a science fiction fan—he was close friends with Robert A. Heinlein—but any resemblance to the Directrix was coincidental, or, at best, an instance of convergence as fiction and reality addressed the same set of problems. (An excellent analysis of the situation can be found in Ed Wysocki’s very useful book An Astounding War.)

If Campbell was tempted to overstate Smith’s influence, this isn’t surprising—the editor was disappointed that science fiction hadn’t played the role that he had envisioned for it in the war, and this wasn’t the first or last time that he would gently exaggerate it. Fifteen years later, however, Smith’s fiction had a profound impact on a very different field. In 1962, Steve Russell of M.I.T. developed Spacewar, the first video game to be played on more than one computer, with two spaceships dueling with torpedoes in the gravity well of a star. In an article for Rolling Stone written by my hero Stewart Brand, Russell recalled:

We had this brand new PDP-1…It was the first minicomputer, ridiculously inexpensive for its time. And it was just sitting there. It had a console typewriter that worked right, which was rare, and a paper tape reader and a cathode ray tube display…Somebody had built some little pattern-generating programs which made interesting patterns like a kaleidoscope. Not a very good demonstration. Here was this display that could do all sorts of good things! So we started talking about it, figuring what would be interesting displays. We decided that probably you could make a two-dimensional maneuvering sort of thing, and decided that naturally the obvious thing to do was spaceships…

I had just finished reading Doc Smith’s Lensman series. He was some sort of scientist but he wrote this really dashing brand of science fiction. The details were very good and it had an excellent pace. His heroes had a strong tendency to get pursued by the villain across the galaxy and have to invent their way out of their problem while they were being pursued. That sort of action was the thing that suggested Spacewar. He had some very glowing descriptions of spaceship encounters and space fleet maneuvers.

The “somebody” whom he mentions was Marvin Minsky, another science fiction fan, and Russell’s collaborator Martin Graetz elsewhere cited Smith’s earlier Skylark series as an influence on the game.

But the really strange thing is that Campbell, who had been eager to claim credit for Smith when it came to the C.I.C., never made this connection in print, at least not as far as I know, although he was hugely interested in Spacewar. In the July 1971 issue of Analog, he published an article on the game by Albert W. Kuhfeld, who had developed a variation of it at the University of Minnesota. Campbell wrote in his introductory note:

For nearly a dozen years I’ve been trying to get an article on the remarkable educational game invented at M.I.T. It’s a great game, involving genuine skill in solving velocity and angular relation problems—but I’m afraid it will never be widely popular. The playing “board” costs about a quarter of a megabuck!