Posts Tagged ‘The Outer Reach’

The Return of “Retention”

Back in 2017, the audio anthology series The Outer Reach released an episode based on my dystopian two-person play “Retention,” which was performed by Aparna Nancherla and Echo Kellum. It’s one of my personal favorites of all my work—I talk about its origins here—and I’ve been delighted to see it come back over the last few months in no fewer than three different forms. The original recording, which was behind a paywall for years, is now available to stream for free through the network Maximum Fun. A wonderful new rendition narrated by Jonathan Todd Ross and Catherine Ho is included in my audio short story collection Syndromes. Perhaps best of all, the print adaptation appears in the July/August 2020 issue of Analog Science Fiction & Fact, which is on sale now. Because I’m hard at work on my current book project, this will probably be my last story in Analog for a while, and I can’t think of a better way to close out my recent run than with “Retention.” I’m very proud of all three versions, which interpret the same underlying text with intriguingly varied results, and I hope you’ll check at least one of them out.

The audio file

When you spend most of your working life typing in silence, it can be disorienting to hear your own words spoken out loud. Writers are often advised to read their writing aloud to check the rhythm, but I’ve never gotten into the habit, and I tend to be more obsessed with how the result looks on the page. As a result, whenever I encounter an audio version of something I’ve written, it feels disorienting, like hearing my own voice on tape. I vividly remember listening to StarShipSofa’s version of “The Boneless One,” narrated by Josh Roseman, while holding my newborn daughter in the hospital, and if everything goes as planned, another publisher will release an audio anthology that includes my novella “The Proving Ground”—which was recently named a notable story in the upcoming edition of The Best American Science Fiction and Fantasy—within the next couple of months. And the most memorable project of all was “Retention,” my episode of the science fiction audio series The Outer Reach, which was performed by Aparna Nancherla and Echo Kellum. I’ve never forgotten the result, but listening to it was such an emotionally charged experience that I’ve only managed to play it once. (Hearing the finished product was gratifying, but the process also cured me of any desire to write words for actors. It’s exciting when it happens, but also requires a degree of detachment that I don’t currently possess.)

I mention all this now because an excerpt of the audiobook version of Astounding has just been posted on SoundCloud. It’s about five minutes long, and it includes the opening section of the first chapter, which recounts a rather strange incident—involving drugs, mirrors, and hypnosis—from the partnership of John W. Campbell and L. Ron Hubbard in the early days of dianetics. The narrator is Sean Runnette, who certainly knows the territory, with previous credits that include Heinlein’s The Number of the Beast and the novel that was the basis for The Meg. He does a great job, and although I haven’t heard the rest, which comes to more than thirteen hours, I suspect that I’m going to end up playing all of it. One of the hardest parts of writing anything is putting enough distance between yourself and your work so that you can review it objectively. For a short story, I’ve found that a few weeks is long enough, but in the case of a novel, it can take months, or even longer. And I’m not remotely close to that point yet with this book. Listening to this audio sample, however, I finally felt as if it had been written by somebody else, as if the translation from one medium into another had yielded the same effect that I normally get from distance in time. (Which may be the real reason why reading your work out loud might be a good idea.) I’m glad that this audio version exists for a lot of reasons, but I’m especially grateful for the new perspective that it offers on this book, which I wrote largely because it was something that I wanted to read. And so far, I actually like it.

Listening to “Retention,” Part 3

Note: I’m discussing the origins of “Retention,” the episode that I wrote for the audio science fiction anthology series The Outer Reach. It’s available for streaming here on the Howl podcast network, and you can get a free month of access by using the promotional code REACH.

One of the unsung benefits of writing for film, television, or radio is that it requires the writer to conform to a fixed format on the printed page. The stylistic conventions of the screenplay originally evolved for the sake of everyone but the screenwriter: it’s full of small courtesies for the director, actors, sound editor, production designer, and line producer, and in theory, it’s supposed to result in one minute of running time per page—although, in practice, the differences between filmmakers and genres make even this rule of thumb almost meaningless. But it also offers certain advantages for writers, too, even if it’s mostly by accident. It can be helpful for authors to force themselves to work within the typeface, margins, and arbitrary formatting rules that the script imposes: it leaves them with minimal freedom except in the choice of the words themselves. Because all the dialogue is indented, you can see the balance between talk and action at a glance, and you eventually develop an intuition about how a good script should look when you flip rapidly through the pages. (The average studio executive, I suspect, rarely does much more than this.) Its typographical constraints amount to a kind of poetic form, and you find yourself thinking in terms of the logic of that space. As the screenwriter Terry Rossio put it:

In retrospect, my dedication—or my obsession—toward getting the script to look exactly the way it should, no matter how long it took—that’s an example of the sort of focus one needs to make it in this industry…If you find yourself with this sort of obsessive behavior—like coming up with inventive ways to cheat the page count!—then, I think, you’ve got the right kind of attitude to make it in Hollywood.

When it came time to write “Retention,” I was looking forward to working within a new template: the radio play. I studied other radio scripts and did my best to make the final result look right. This was more for my own sake than for anybody else’s, and I’m pretty sure that my producer would have been happy to get a readable script in any form. But I had a feeling that it would be helpful to adapt my habitual style to the standard format, and it was. In many ways, this story was a more straightforward piece of writing than most: it’s just two actors talking with minimal sound effects. Yet the stark look of the radio script, which consists of nothing but numbered lines of dialogue alternating between characters, had a way of clarifying the backbone of the narrative. Once I had an outline, I began by typing the dialogue as quickly as I could, almost in real time, without even indicating the identities of the speakers. Then I copied and pasted the transcript—which is how I came to think of it—into the radio play template. For the second draft, I found myself making small changes, as I always do, so that the result would look good on the page, rewriting lines to make for an even right margin and tightening speeches so that they wouldn’t fall across a page break. My goal was to come up with a document that would be readable and compelling in itself. And what distinguished it from my other projects was that I knew that it would ultimately be translated into performance, which was how its intended audience would experience it.

I delivered a draft of the script to Nick White, my producer, on January 8, 2016, which should give you a sense of how long it takes for something like this to come to fruition. Nick made a few edits, and I did one more pass on the whole thing, but we essentially had a finished version by the end of the month. After that, there was a long stretch of waiting, as we ran the script past the Howl network and began the process of casting. It went out to a number of potential actors, and it wasn’t until September that Aparna Nancherla and Echo Kellum came on board. (I also finally got paid for the script, which was noteworthy in itself—not many similar projects can afford to pay their writers. The amount was fairly modest, but it was more than reasonable for what amounted to a week of work.) In November, I got a rough cut of the episode, and I was able to make a few small suggestions. Finally, on December 21, it premiered online. All told, it took about a year to transform my initial idea into fifteen minutes of audio, so I was able to listen to the result with a decent amount of detachment. I’m relieved to say that I’m pleased with how it turned out. Casting Aparna Nancherla as Lisa, in particular, was an inspired touch. And although I hadn’t anticipated the decision to process her voice to make it more obvious from the beginning that she was a chatbot, on balance, I think that it was a valid choice. It’s probably the most predictable of the story’s twists, and by tipping it in advance, it serves as a kind of mislead for listeners, who might catch onto it quickly and conclude, incorrectly, that it was the only surprise in store.

What I found most interesting about the whole process was how it felt to deliver what amounted to a blueprint of a story for others to execute. Playwrights and screenwriters do it all the time, but for me, it was a novel experience: I may not be entirely happy with every story I’ve published, but they’re all mine, and I bear full responsibility for the outcome. “Retention” gave me a taste, in a modest way, of how it feels to hand an idea over to someone else, and of the peculiar relationship between a script and the dramatic work itself. Many aspiring screenwriters like to think that their vision on the page is complete, but it isn’t, and it has to pass through many intermediaries—the actors, the producer, the editor, the technical team—before it comes out on the other side. On balance, I prefer writing my own stuff, but I came away from “Retention” with valuable lessons that I expect to put into practice, whether or not I write for audio again. (I’m hopeful that there will be a second season of The Outer Reach, and I’d love to be a part of it, but its future is still up in the air.) I’ve spent most of my career worrying about issues of clarity, and in the case of a script, this isn’t an abstract goal, but a strategic element that can determine how faithfully the story is translated into its final form. Any fuzzy thinking early on will only be magnified in subsequent stages, so there’s a huge incentive for the writer to make the pieces as transparent and logical as possible. This is especially true when you’re providing a sketch for someone else to finish, but it also applies when you’re writing for ordinary readers, who are doing nothing else, after all, but turning the story into a movie in their heads.

Listening to “Retention,” Part 2

Note: I’m discussing the origins of “Retention,” the episode that I wrote for the audio science fiction anthology series The Outer Reach. It’s available for streaming here on the Howl podcast network, and you can get a free month of access by using the promotional code REACH.

Yesterday, I described how I came up with the premise of “Retention,” which consists entirely of a recording of a telephone call in which a customer tries to get a service representative from a cable company to cancel his account. The primary difference between this conversation and the equally infuriating ones that happen every day is that it takes place at some undefined point in the future, which immediately opened up two possible avenues of exploration. First, there was the question of what kind of services are being provided. It wasn’t hard to imagine a scenario in which companies like Comcast have taken over every aspect of our lives, with algorithms automatically delivering content and services based on our user profiles, until we’re both totally dependent on the system and increasingly isolated from others. This wasn’t the most original idea in the world—Black Mirror, among others, has mined this territory before—but I had fun with it. The other question was who, exactly, was having this conversation. I had the notion early on that the service representative was actually a chatbot, or an artificial intelligence programmed to mimic a real person, which is one of the first possibilities that would have occurred to anybody. (In the finished episode, there isn’t much of an attempt to hide it.) But I also wondered if it might be possible to have the customer be an artificial intelligence as well: an emergent property of the system that accidentally arose from the client’s preferences and search history. The original customer might not even exist. And at that point, I knew that I had a story.

I’ve been interested in the concept of the Turing Test and conversations with artificial intelligences for a long time, ever since reading the hilarious dialogue in Metamagical Themas between Douglas R. Hofstadter and what claimed to be a computer program named Nicolai. (If you’ve never read it before, please drop everything and check it out here—just search for the words “Post Scriptum.”) Two of the most famous early chatbots were ELIZA, which was meant to simulate a psychiatrist, and PARRY, a simulation of a patient with schizophrenia. These personalities were chosen because they offered limited, stereotyped ways of speaking that would be easier to imitate, but they also complemented each other in obvious ways, so it’s no surprise that someone decided to see what happened when the two programs spoke to each other, which they did in 1972. Here’s a short excerpt from the full conversation:

ELIZA: What else would you like to discuss?

PARRY: I am getting tired of answering the same questions over and over.

ELIZA: What resemblance do you see?

PARRY: Why do you need to know that?

ELIZA: What do you think?

PARRY: I don’t understand your motives.

ELIZA: Why don’t you understand my motives?

Under the circumstances, it’s not surprising that neither program was at its best: each one depended on the use of canned phrases, repetition, and leading questions to keep the conversation going, which didn’t give them much to work with in the absence of a human partner. But I’ve never forgotten the idea of two chatbots talking to each other. The final transcript of the conversation between ELIZA and PARRY runs about six pages, but in theory, it could have continued endlessly, with the two programs going back and forth to this very day. (It isn’t the only time that two bots have faced off, either: earlier this year, an interminable conversation between two Google Homes named Vladimir and Estragon led to a brief flurry of interest online.) It seemed to me that I could write something poignant and creepy about a customer service call that never ended because it inadvertently paired off two artificial intelligences. One would be programmed to retain the client at all costs; the other would be determined to cancel its account. Their objectives would be clearly defined and mutually inconsistent, and as long as neither one of them crashed, they would keep arguing forever. In the finished script, my two characters, whom I named Lisa and Perry in a nod to their predecessors, wind up talking for something like eight hundred years, and the episode fades out before they finish. I wasn’t quite sure what the tone of the resulting story would be, but I assumed that one would emerge naturally if I laid all the pieces end to end.

At this point, I had a decent spine for the script, and the rest amounted to a series of technical challenges. The story fell logically into several segments, each one of which was defined by a twist. There was Perry’s desire to cancel his account and Lisa’s reluctance to allow it; the gradual disclosure of the extent to which the system has taken over its clients’ lives; the reveal that Lisa is a bot and, later, that Perry is one, too; and the revelation at the end that they’ve been talking for centuries. Writing it became a matter of figuring out how to convey this information organically over the course of the conversation. Fortunately, I had a lot of material. I listened to the recording of Ryan Block’s conversation with Comcast several times and noted down scraps of potential dialogue. Even better, I found a copy of the Comcast quality guidelines for customer retention, which amounts to a script that representatives are supposed to follow, complete with canned phrases—“I understand that your needs have changed and you want your services to reflect that”—that wouldn’t be out of place in ELIZA’s programming. The rest practically wrote itself. What I liked the most about it is that it fulfilled my original goal, which was to write a story that was inseparable from the audio format. Not only does it lend itself to a podcast, but it wouldn’t be possible in any other form: the two characters are both disembodied intelligences, but you aren’t supposed to realize this right away, and I can’t think of another medium in which it would work. Tomorrow, I’ll talk about what happened after I delivered the script to my producer, and how I feel about the finished episode itself.

Listening to “Retention,” Part 1

Note: For the next three days, I’m going to be discussing the origins of “Retention,” the episode that I wrote for the audio science fiction anthology series The Outer Reach. It’s available for streaming here on the Howl podcast network, and you can get a free month of access by using the promotional code REACH.

Until about a year ago, I had never thought about writing for audio. As I’ve recounted elsewhere, I got into it thanks to a lucky coincidence: I was approached by Nick White, a radio producer in Los Angeles, who had gone to high school with my younger brother. Nick was developing an audio science fiction series, purely as a labor of love, and since he knew that I’d published some stories in Analog, he wanted to know if I’d consider adapting one for the show. I was more than willing, but after taking a hard look at “The Boneless One” and “Cryptids,” I decided that neither one was particularly suited for the format. There were too many characters, for one thing, and it would be hard to make either story work with a smaller cast: the former is a murder mystery with multiple suspects, the latter a monster story that depends on the victims being picked off one by one, and each has about the right number of players. I also couldn’t think of a plausible way to tell them using auditory tools alone. Since I didn’t have an obvious candidate for adaptation, which in itself would probably require at least a week of work, I began to think that it would make more sense for me to write something up from scratch. Nick, fortunately, agreed. And when I started to figure out what kind of plot to put together, one of my first criteria was that it be a story that could be conveyed entirely through dialogue and sound.

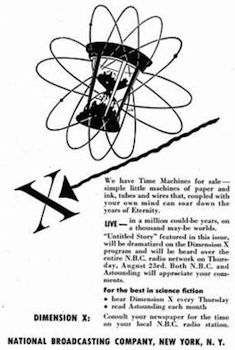

I was probably overthinking it. When I went back recently to listen to old science fiction radio shows like Dimension X and X Minus One, I discovered that they weren’t shy about leaning heavily on narration. Radio playwrights didn’t worry much about honoring to the purity of the medium: they were seasoned professionals who had to get an episode out on time, and by using a narrator, they could tell a wider range of stories with less trouble. (Most of these scripts were adaptations of stories from magazines like Astounding and Galaxy, and many wouldn’t have worked at all without some degree of narration to fill in the gaps between scenes.) Which isn’t to say that they didn’t rely on a few basic principles when it came to dramatizing the situation. For instance, we rarely hear more than two voices at once. Even on the printed page, it can be difficult for the reader to keep track of more than two new characters at a time, and when you don’t have any visual cues, it’s best to restrict the speakers to a number that the listener can easily follow. A scene between two characters, particularly a man and a woman, is immediately more engaging than one in which we have to keep track of three similar male voices. As I concluded in my earlier post on the subject: “If I were trying to adapt a story for radio and didn’t know where to begin, I’d start by asking myself if it could be structured as five two-person dialogue scenes, ideally for one actor and one actress.”

This is the same structure that I ended up using for “Retention,” and I stumbled across it intuitively, as a kind of safety net to make up for my lack of experience. Most of what I know about audio storytelling arises from the fact that I’m married to a professional podcaster, and the first thing you learn about radio journalism is that clarity is key. When you listen to a show like Serial or Invisibilia, for example, you soon become aware of how obsessively organized it all is, even while it maintains what feels like a chatty, informal tone. Whenever the hosts introduce a new character or story, they tell us to sit tight, reassuring us that we’ll circle back soon to the central thread of the episode, and they’ll often inform us of exactly how many minutes an apparent digression will last. This sort of handholding is crucial, because you can’t easily rewind to listen to a section that seems unclear. If you stop to figure out what you’ve just been told, you’ll miss what comes next. That’s why radio shows are constantly telling us what to think about what we’re hearing. As Ira Glass put it in Radio: An Illustrated Guide:

This is the structure of every story on our program—there’s an anecdote, that is, a sequence of actions where someone says “this happened then this happened then this happened”—and then there’s a moment of reflection about what that sequence means, and then on to the next sequence of actions…Anecdote then reflection, over and over.

I didn’t necessarily want to do this for my script, but for the sake of narrative clarity, I decided to follow an analogous set of rules. When I write fiction, I always try to structure the plot as a series of clear objectives, mostly to keep the reader grounded, and it seemed even more critical here. It soon struck me that the best way to orient the listener from the beginning was to start with a readily identifiable kind of “found” audio, and then see what kind of story it suggested. In my earliest emails to Nick, I pitched structuring an episode around an emergency hotline call—which is an idea that I still might use one day—or a series of diary entries from a spacecraft, like ones that the hero records for his daughter in Interstellar. I also began to think about what kinds of audio tend to go viral, which only happens when the situations they present are immediately obvious. And the example that seemed the most promising was the notorious recording of the journalist Ryan Block trying to get a representative from Comcast to cancel his account. What I liked about it was how quickly it establishes the premise. In the final script of “Retention,” the first spoken dialogue is: “Thank you for holding. This call may be recorded or monitored for quality assurance. My name is Lisa. To whom am I speaking?” A few lines later, Perry, the customer, says: “I want to disconnect my security system and close my account, please.” At that point, after less than thirty seconds, we know what the story is about. Tomorrow, I’ll talk more about how the structure of a customer service call freed me to follow the story into strange places, and how I was inspired by a famous anecdote from the history of artificial intelligence.

Entering The Outer Reach

About a year ago, I got an email from Nick White, a radio producer at KCRW in Los Angeles, who wanted to discuss an audio science fiction show that he was developing. We had heard about each other thanks to a lucky coincidence—Nick had gone to high school with my brother—but I quickly became interested in the project for its own sake. At that point, it didn’t even have a title, and all I knew was that it would be an anthology series of loosely connected stories set in the far future. Nick had already put together a pilot featuring the actor Martin Starr, and he was hoping to commission four more episodes to be released on the Howl FM podcast network. He also had a small budget to pay writers, which is even more remarkable than it sounds. When he asked me if I had any stories that I’d consider adapting, I sent him a link to my novelette “The Boneless One,” which had been released in an audio version by StarShipSofa. In the end, it didn’t seem like a natural fit for the format: it had too many characters, and there was no obvious way to tell it through dialogue and sound alone. Since it seemed as if any adaptation would require at least a week of work, if not more, I started wondering if it might make more sense for me to write something up from scratch. And Nick, fortunately, agreed.

The result is “Retention,” an installment of the original science fiction anthology series The Outer Reach, which debuts today in its entirety on Howl. (If you aren’t already a member, you have to sign up for the service, but the first month is free. The streaming page for the show is here.) Nick put together a great cast—the episode, which consists entirely of a conversation between two characters, is performed by Aparna Nancherla (Inside Amy Schumer) and Echo Kellum (Arrow)—and I’m very happy with the result. I’ll be talking more about how it came together in a future post, but I’ll just say for now that it represents my attempt to write a story that could only be told in an audio format, and that utilized the medium’s logic, rather than fighting against it. Listening to it has been an odd but ultimately gratifying experience. I wrote the script last December, which is long enough ago that I can hear it with detachment, and I don’t feel the same sense of ownership over it that I do with, say, my novella “The Proving Ground,” which appears in the current issue of Analog. “Retention” is the first thing I’ve ever written that I’ve handed over to be realized by somebody else, and I’m relieved to say that I like it. In fact, I like it one hell of a lot. It’s only fifteen minutes long, so please check it out if you’re so inclined, and let me know what you think.