Posts Tagged ‘New York Times’

Back to the Future

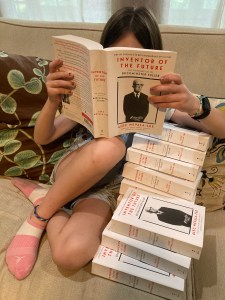

It’s hard to believe, but the paperback edition of Inventor of the Future: The Visionary Life of Buckminster Fuller is finally in stores today. As far as I’m concerned, this is the definitive version of this biography—it incorporates a number of small fixes and revisions—and it marks the culmination of a journey that started more than five years ago. It also feels like a milestone in an eventful writing year that has included a couple of pieces in the New York Times Book Review, an interview with the historian Richard Rhodes on Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer for The Atlantic online, and the usual bits and bobs elsewhere. Most of all, I’ve been busy with my upcoming biography of the Nobel Prize-winning physicist Luis W. Alvarez, which is scheduled to be published by W.W. Norton sometime in 2025. (Oppenheimer fans with sharp eyes and good memories will recall Alvarez as the youthful scientist in Lawrence’s lab, played by Alex Wolff, who shows Oppenheimer the news article announcing that the atom has been split. And believe me, he went on to do a hell of a lot more. I can’t wait to tell you about it.)

Ringing in the new

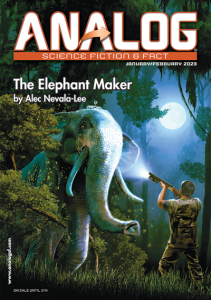

By any measure, I had a pretty productive year as a writer. My book Inventor of the Future: The Visionary Life of Buckminster Fuller was released after more than three years of work, and the reception so far has been very encouraging—it was named a New York Times Book Review Editors’ Choice, an Economist best book of the year, and, wildest of all, one of Esquire‘s fifty best biographies of all time. (My own vote would go to David Thomson’s Rosebud, his fantastically provocative biography of Orson Welles.) On the nonfiction front, I rounded out the year with pieces in Slate (on the misleading claim that Fuller somehow anticipated the principles of cryptocurrency) and the New York Times (on the remarkable British writer R.C. Sherriff and his wonderful novel The Hopkins Manuscript). Best of all, the latest issue of Analog features my 36,000-word novella “The Elephant Maker,” a revised and updated version of an unpublished novel that I started writing in my twenties. Seeing it in print, along with Inventor of the Future, feels like the end of an era for me, and I’m not sure what the next chapter will bring. But once I know, you’ll hear about it here first.

A Geodesic Life

After three years of work—and more than a few twists and turns—my latest book, Inventor of the Future: The Visionary Life of Buckminster Fuller, is finally here. I think it’s the best thing that I’ve ever done, or at least the one book that I’m proudest to have written. After last week’s writeup in The Economist, a nice review ran this morning in the New York Times, which is a dream come true, and you can check out excerpts today at Fast Company and Slate. (At least one more should be running this weekend in The Daily Beast.) If you want to hear more about it from me, I’m doing a virtual event today sponsored by the Buckminster Fuller Institute, and on Saturday August 13, I’ll be holding a discussion at the Oak Park Public Library with Sarah Holian of the Frank Lloyd Wright Trust, which will be also be available to view online. There’s a lot more to say here, and I expect to keep talking about Fuller for the rest of my life, but for now, I’m just delighted and relieved to see it out in the world at last.

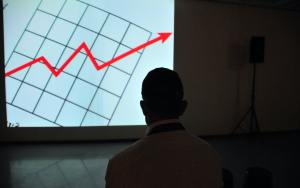

The Singularity is Near

My latest science fiction story, “Singularity Day,” is currently featured on Curious Fictions, an online publishing platform that allows authors to share their work directly with readers. It was originally written as a submission to the “Op-Eds From the Future” series at the New York Times, which was sadly discontinued earlier this year, but I liked how it turned out—it’s one of my few successful attempts at a short short story—and I decided to release it in this format as a little experiment. It’s a very quick read, and it’s free, so I hope you’ll take a look!

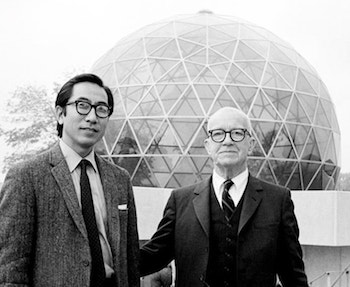

Shoji Sadao (1926-2019)

The architect Shoji Sadao—who worked closely with Buckminster Fuller and the sculptor Isamu Noguchi—passed away earlier this month in Tokyo. I’m briefly quoted in Sadao’s obituary in the New York Times, which draws attention to his largely unsung role in the careers of these two brilliant but demanding men. My contact with Sadao was limited to a few emails and one short phone conversation intended to set up an interview that I’m sorry will never happen, but I’ll be discussing his legacy at length in my upcoming biography of Fuller, and you’ll be hearing a lot more about him here.

Burrowing into The Tunnel

Last fall, it occurred to me that someone should write an essay on the parallels between the novel The Tunnel by William H. Gass, which was published in 1995, and the contemporary situation in America. Since nobody else seemed to be doing it, I figured that it might as well be me, although it was a daunting project even to contemplate—Gass’s novel is over six hundred pages long and famously impenetrable, and I knew that doing it justice would take at least three weeks of work. Yet it seemed like something that had to exist, so I wrote it up at the end of last year. For various reasons, it took a long time to see print, but it’s finally out now in the New York Times Book Review. It isn’t the kind of thing that I normally do, but it felt like a necessary piece, and I’m pretty proud of how it turned out. And if the intervening seven months don’t seem to have dated it at all, it only puts me in mind of what the radio host on The Simpsons once said about the DJ 3000 computer: “How does it keep up with the news like that?”

Outside the Wall

On Thursday, I’m heading out to the fortieth annual International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts in Orlando, Florida, where I’ll be participating in two events. One will be a reading at 8:30am featuring Jeanne Beckwith, James Patrick Kelly, Rachel Swirsky, and myself, moderated by Marco Palmieri. (I’m really looking forward to meeting Jim Kelly, who had an unforgettable story, “Monsters,” in the issue of Asimov’s Science Fiction that changed my life.) The other will be the panel “The Changing Canon of SF” at 4:15pm, moderated by James Patrick Kelly, at which Mary Anne Mohanraj, Rich Larson, and Erin Roberts will also be appearing.

In other news, I’m scheduled to speak next month at the Windy City Pulp and Paper Convention in Lombard, Illinois, where I’ll be giving a talk on Friday April 12 at 7pm. (Hugo nominations close soon, by the way, and if you’re planning to fill out a ballot, I’d be grateful if you’d consider nominating Astounding for Best Related Work.) And if you haven’t already seen it, please check out my recent review in the New York Times of John Lanchester’s dystopian novel The Wall. I should have a few more announcements here soon—please stay tuned for more!

Visions of tomorrow

As I’ve mentioned here before, one of my few real regrets about Astounding is that I wasn’t able to devote much room to discussing the artists who played such an important role in the evolution of science fiction. (The more I think about it, the more it seems to me that their collective impact might be even greater than that of any of the writers I discuss, at least when it comes to how the genre influenced and was received by mainstream culture.) Over the last few months, I’ve done my best to address this omission, with a series of posts on such subjects as Campbell’s efforts to improve the artwork, his deliberate destruction of the covers of Unknown, and his surprising affection for the homoerotic paintings of Alejandro Cañedo. And I can reveal now that this was all in preparation for a more ambitious project that has been in the works for a while—a visual essay on the art of Astounding and Unknown that has finally appeared online in the New York Times Book Review, with the highlights scheduled to be published in the print edition this weekend. It took a lot of time and effort to put it together, especially by my editors, and I’m very proud of the result, which honors the visions of such artists as H.W. Wesso, Howard V. Brown, Hubert Rogers, Manuel Rey Isip, Frank Kelly Freas, and many others. It stands on its own, but I’ve come to think of it as an unpublished chapter from my book that deserves to be read alongside its longer companion. As I note in the article, it took years for the stories inside the magazine to catch up to the dreams of its readers, but the artwork was often remarkable from the beginning. And if you want to know what the fans of the golden age really saw when they imagined the future, the answer is right here.

The unfinished lives

Yesterday, the New York Times published a long profile of Donald Knuth, the legendary author of The Art of Computer Programming. Knuth is eighty now, and the article by Siobhan Roberts offers an evocative look at an intellectual giant in twilight:

Dr. Knuth usually dresses like the youthful geek he was when he embarked on this odyssey: long-sleeved T-shirt under a short-sleeved T-shirt, with jeans, at least at this time of year…Dr. Knuth lives in Stanford, and allowed for a Sunday visitor. That he spared an entire day was exceptional—usually his availability is “modulo nap time,” a sacred daily ritual from 1 p.m. to 4 p.m. He started early, at Palo Alto’s First Lutheran Church, where he delivered a Sunday school lesson to a standing-room-only crowd.

This year marks the fiftieth anniversary of the publication of the first volume of Knuth’s most famous work, which is still incomplete. Knuth is busy writing the fourth installment, one fascicle at a time, although its most recent piece has been delayed “because he keeps finding more and more irresistible problems that he wants to present.” As Roberts writes: “Dr. Knuth’s exacting standards, literary and otherwise, may explain why his life’s work is nowhere near done. He has a wager with Sergey Brin, the co-founder of Google and a former student…over whether Mr. Brin will finish his Ph.D. before Dr. Knuth concludes his opus…He figures it will take another twenty-five years to finish The Art of Computer Programming, although that time frame has been a constant since about 1980.”

Knuth is a prominent example, although far from the most famous, of a literary and actuarial phenomenon that has grown increasingly familiar—an older author with a projected work of multiple volumes, published one book at a time, that seems increasingly unlikely to ever see completion. On the fiction side, the most noteworthy case has to be that of George R.R. Martin, who has been fielding anxious inquiries from fans for most of the last decade. (In an article that appeared seven long years ago in The New Yorker, Laura Miller quotes Martin, who was only sixty-three at the time: “I’m still getting e-mail from assholes who call me lazy for not finishing the book sooner. They say, ‘You better not pull a Jordan.’”) Robert A. Caro is still laboring over what he hopes will be the final volume of his biography of Lyndon Johnson, and mortality has become an issue not just for him, but for his longtime editor, as we read in Charles McGrath’s classic profile in the Times:

Robert Gottlieb, who signed up Caro to do The Years of Lyndon Johnson when he was editor in chief of Knopf, has continued to edit all of Caro’s books, even after officially leaving the company. Not long ago he said he told Caro: “Let’s look at this situation actuarially. I’m now eighty, and you are seventy-five. The actuarial odds are that if you take however many more years you’re going to take, I’m not going to be here.”

That was six years ago, and both men are still working hard. But sometimes a writer has no choice but to face the inevitable. When asked about the concluding fifth volume of his life of Picasso, with the fourth one still on the way, the biographer John Richardson said candidly: “Listen, I’m ninety-one—I don’t think I have time for that.”

I don’t have the numbers to back this up, but such cases—or at least the public attention that they inspire—seem to be growing more common these days, on account of some combination of lengthening lifespans, increased media coverage of writers at work, and a greater willingness from publishers to agree to multiple volumes in the first place. The subjects of such extended commitments tend to be monumental in themselves, in order to justify the total investment of the writer’s own lifetime, and expanding ambitions are often to blame for blown deadlines. Martin, Caro, and Knuth all increased the prospective number of volumes after their projects were already underway, or as Roberts puts it: “When Dr. Knuth started out, he intended to write a single work. Soon after, computer science underwent its Big Bang, so he reimagined and recast the project in seven volumes.” And this “recasting” seems particularly common in the world of biographies, as the author discovers more material that he can’t bear to cut. The first few volumes may have been produced with relative ease, but as the years pass and anticipation rises, the length of time it takes to write the next installment grows, until it becomes theoretically infinite. Such a radical change of plans, which can involve extending the writing process for decades, or even beyond the author’s natural lifespan, requires an indulgent publisher, university, or other benefactor. (John Richardson’s book has been underwritten by nothing less than the John Richardson Fund for Picasso Research, which reminds me of what Homer Simpson said after being informed that he suffered from Homer Simpson syndrome: “Oh, why me?”) And it may not be an accident that many of the examples that first come to mind are white men, who have the cultural position and privilege to take their time.

It isn’t hard to understand a writer’s reluctance to let go of a subject, the pressures on a book being written in plain sight, or the tempting prospect of working on the same project forever. And the image of such authors confronting their mortality in the face of an unfinished book is often deeply moving. One of the most touching examples is that of Joseph Needham, whose Science and Civilization in China may have undergone the most dramatic expansion of them all, from an intended single volume to twenty-seven and counting. As Kenneth Girdwood Robinson writes in a concluding posthumous volume:

The Duke of Edinburgh, Chancellor of the University of Cambridge, visited The Needham Research Institute, and interested himself in the progress of the project. “And how long will it take to finish it?” he enquired. On being given a rather conservative answer, “At least ten years,” he exclaimed, “Good God, man, Joseph will be dead before you’ve finished,” a very true appreciation of the situation…In his closing years, though his mind remained lucid and his memory astonishing, Needham had great difficulty even in moving from one chair to another, and even more difficulty in speaking and in making himself understood, due to the effect of the medicines he took to control Parkinsonism. But a secretary, working closely with him day by day, could often understand what he had said, and could read what he had written, when others were baffled.

Needham’s decline eventually became impossible to ignore by those who knew him best, as his biographer Simon Winchester writes in The Man Who Loved China: “It was suggested that, for the first time in memory, he take the day off. It was a Friday, after all: he could make it a long weekend. He could charge his batteries for the week ahead. ‘All right,’ he said. ‘I’ll stay at home.’” He died later that day, with his book still unfinished. But it had been a good life.

Go set a playwright

If you follow theatrical gossip as avidly as I do, you’re probably aware of the unexpected drama that briefly surrounded the new Broadway adaptation of Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, which was written for the stage by Aaron Sorkin. In March, Lee’s estate sued producer Scott Rudin, claiming that the production was in breach of contract for straying drastically from the book. According to the original agreement, the new version wasn’t supposed to “depart in any manner from the spirit of the novel nor alter its characters,” which Sorkin’s interpretation unquestionably did. (Rudin says just as much on the record: “I can’t and won’t present a play that feels like it was written in the year the book was written in terms of its racial politics. It wouldn’t be of interest. The world has changed since then.”) But the question isn’t quite as straightforward as it seems. As a lawyer consulted by the New York Times explains:

Does “spirit” have a definite and precise meaning, or could there be a difference of opinion as to what is “the spirit” of the novel? I do not think that a dictionary definition of “spirit” will resolve that question. Similarly, the contract states that the characters should not be altered. In its pre-action letter, Harper Lee’s estate repeatedly states that the characters “would never have” and “would not have” done numerous things; unless as a matter of historical fact the characters would not have done something…who is to say what a creature of fiction “would never have” or “would not have” done?

Now that the suit has been settled and the play is finally on Broadway, this might all seem beside the point, but there’s one aspect of the story that I think deserves further exploration. Earlier this week, Sorkin spoke to Greg Evans of Deadline about his writing process, noting that he took the initial call from Rudin for good reasons: “The last three times Scott called me and said ‘I have something very exciting to talk to you about,’ I ended up writing Social Network, Moneyball, and Steve Jobs, so I was paying attention.” His first pass was a faithful version of the original story, which took him about six months to write: “I had just taken the greatest hits of the book, the most important themes, the most necessary themes. I stood them up and dramatized them. I turned them into dialogue.” When he was finished, he had a fateful meeting with Rudin:

He had two notes. The first was, “We’ve got to get to the trial sooner.” That’s a structural note. The second was the note that changed everything. He said, “Atticus can’t be Atticus for the whole play. He’s got to become Atticus,” and of course, he was right. A protagonist has to change. A protagonist has to be put through something and change as a result, and a protagonist has to have a flaw. And I wondered how Harper Lee had gotten away with having Atticus be Atticus for the whole book, and it’s because Atticus isn’t the protagonist in the book. Scout is. But in the play, Atticus was going to be the protagonist, and I threw out that first draft. I started all over again, but this time the goal wasn’t to be as much like the book as possible. The goal wasn’t to swaddle the book in bubble wrap and then gently transfer it to a stage. I was going to write a new play.

This is fascinating stuff, but it’s worth emphasizing that while Rudin’s first piece of feedback was “a structural note,” the second one was as well. The notions that “a protagonist has to change” and “a protagonist has to have a flaw” are narrative conventions that have evolved over time, and for good reason. Like the idea of building the action around a clear sequence of objectives, they’re basically artificial constructs that have little to do with the accurate representation of life. Some people never change for years, and while we’re all flawed in one way or another, our faults aren’t always reflected in dramatic terms in the situations in which we find ourselves. These rules are useful primarily for structuring the audience’s experience, which comes down to the ability to process and remember information delivered over time. (As Kurt Vonnegut, who otherwise might not seem to have much in common with Harper Lee, once said to The Paris Review: “I don’t praise plots as accurate representations of life, but as ways to keep readers reading.”) Yet they aren’t essential, either, as the written and filmed versions of To Kill a Mockingbird make clear. The original novel, in particular, has a rock-solid plot and supporting characters who can change and surprise us in ways that Atticus can’t. Unfortunately, it’s hard for plot alone to carry a play, which is largely a form about character, and Atticus is obviously the star part. Sorkin doesn’t shy away from using the backbone that Lee provides—the play does indeed get to the jury trial, which is still the most reliable dramatic convention ever devised, more quickly than the book does—but he also grasped the need to turn the main character into someone who could give shape to the audience’s experience of watching the play. It was this consideration, and not the politics, that turned out to be crucial.

There are two morals to this story. One is how someone like Sorkin, who can fall into traps of his own as a writer, benefits from feedback from even stronger personalities. The other is how a note on structure, which Sorkin takes seriously, forced him to engage more deeply with the play’s real material. As all writers know, it’s harder than it looks to sequence a story as a series of objectives or to depict a change in the protagonist, but simply by thinking about such fundamental units of narrative, a writer will come up with new insights, not just about the hero, but about everyone else. As Sorkin says of his lead character in an interview with Vulture:

He becomes Atticus Finch by the end of the play, and while he’s going along, he has a kind of running argument with Calpurnia, the housekeeper, which is a much bigger role in the play I just wrote. He is in denial about his neighbors and his friends and the world around him, that it is as racist as it is, that a Maycomb County jury could possibly put Tom Robinson in jail when it’s so obvious what happened here. He becomes an apologist for these people.

In other words, Sorkin’s new perspective on Atticus also required him to rethink the roles of Calpurnia and Tom Robinson, which may turn out to be the most beneficial change of all. (This didn’t sit well with the Harper Lee estate, which protested in its complaint that black characters who “knew their place” wouldn’t behave this way at the time.) As Sorkin says of their lack of agency in the original novel: “It’s noticeable, it’s wrong, and it’s also a wasted opportunity.” That’s exactly right—and I like the last reason the best. In theater, as in any other form of narrative, the technical considerations of storytelling are more important than doing the right thing. But to any experienced writer, it’s also clear that they’re usually one and the same.

The Great Man and the WASP

Last week, the New York Times opinion columnist Ross Douthat published a piece called “Why We Miss the WASPs.” Newspaper writers don’t get to choose their own headlines, and it’s possible that if the essay had run under a different title, it might not have attracted the same degree of attention, which was far from flattering. Douthat’s argument—which was inspired by the death of George H.W. Bush and his obvious contrast with the current occupant of the White House—can be summarized concisely:

Bush nostalgia [is] a longing for something America used to have and doesn’t really any more—a ruling class that was widely (not universally, but more widely than today) deemed legitimate, and that inspired various kinds of trust (intergenerational, institutional) conspicuously absent in our society today. Put simply, Americans miss Bush because we miss the WASPs—because we feel, at some level, that their more meritocratic and diverse and secular successors rule us neither as wisely nor as well.

Douthat ostentatiously concedes one point to his critics in advance: “The old ruling class was bigoted and exclusive and often cruel, it had failures aplenty, and as a Catholic I hold no brief for its theology.” But he immediately adds that “building a more democratic and inclusive ruling class is harder than it looks, and even perhaps a contradiction in terms,” and he suggests that one solution would be a renewed embrace of the idea that “a ruling class should acknowledge itself for what it really is, and act accordingly.”

Not surprisingly, Douthat’s assumptions about the desirable qualities of “a ruling class” were widely derided. He responded with a followup piece in which he lamented the “misreadings” of those who saw his column as “a paean to white privilege, even a brief for white supremacy,” while never acknowledging any flaws in his argument’s presentation. But what really sticks with me is the language of the first article, which is loaded with rhetorical devices that both skate lightly over its problems and make it difficult to deal honestly with the issues that it raises. One strategy, which may well have been unconscious, is a familiar kind of distancing. As Michael Harriot writes in The Root:

I must applaud opinion writer Ross Douthat for managing to put himself at an arms-length distance from the opinions he espoused. Douthat employed the oft-used Fox News, Trumpian “people are saying…” trick, essentially explaining that some white people think like this. Not him particularly—but some people.

It’s a form of evasiveness that resembles the mysterious “you” of other sorts of criticism, and it enables certain opinions to make it safely into print. Go back and rewrite the entire article in the first person, and it becomes all but unreadable. For instance, it’s hard to imagine Douthat writing a sentence like this: “I miss Bush because I miss the WASPs—because I feel, at some level, that their more meritocratic and diverse and secular successors rule us neither as wisely nor as well.”

But even as Douthat slips free from the implications of his argument on one end, he’s ensnared at the other by his own language. We can start with the term “ruling class” itself, which appears in the article no fewer than five times, along with a sixth instance in a quotation from the critic Helen Andrews. The word “establishment” appears seventeen times. If asked, Douthat might explain that he’s using both of these terms in a neutral sense, simply to signify the people who end up in political office or in other positions of power. But like the “great man” narrative of history or the “competent man” of science fiction, these words lock us into a certain set of assumptions, by evoking an established class that rules rather than represents, and they beg the rather important question of whether we need a ruling class at all. Even more insidiously, Douthat’s entire argument rests on the existence of the pesky but convenient word “WASP” itself. When the term appeared half a century ago, it was descriptive and slightly pejorative. (According to the political scientist Andrew Harris, who first used it in print, it originated in the “the cocktail party jargon of the sociologists,” and the initial letter initially stood for “wealthy.” As it stands, the term is slightly redundant, although it still describes exactly the same group of people, and foregrounding their whiteness isn’t necessarily a bad idea.) Ultimately, however, it turned into a tag that allows us to avoid spelling out everything that it includes, which makes it easier to let such attitudes slip by unexamined. Let’s rework that earlier sentence one more time: “I miss Bush because I miss the white Anglo-Saxon Protestants—because I feel, at some level, that their more meritocratic and diverse and secular successors rule us neither as wisely nor as well.” And this version, at least, is much harder to “misread.”

At this point, I should probably confess that I take a personal interest in everything that Douthat writes. Not only are we both Ivy Leaguers, but we’re members of the same college class, although I don’t think we ever crossed paths. In most other respects, we don’t have a lot in common, but I can relate firsthand to the kind of educational experience—which John Stuart Mill describes in today’s quotation—that leads public intellectuals to become more limited in their views than they might realize. Inspired by a love of the great books and my summer at St. John’s College, I spent most of my undergraduate years reading an established canon of writers, in part because I was drawn to an idea of elitism in its most positive sense. What I didn’t see for a long time was that I was living in an echo chamber. It takes certain forms of privilege and status for granted, and it makes it hard to talk about these matters in the real world without a conscious effort of will. (In his original article, Douthat’s sense of the possible objections to his thesis is remarkably blinkered in itself. After acknowledging the old ruling class’s bigotry, exclusivity, and cruelty, he adds: “And don’t get me started on its Masonry.” That was fairly low down my list of concerns, but now I’m frankly curious.) I understand where Douthat is coming from, because I came from it, too. But that isn’t an excuse for looking at the WASPs, or a dynasty that made a fortune in the oil business, and feeling “nostalgic for their competence,” which falls apart the second we start to examine it. If they did rule us once, then they bear responsibility for the destruction of our planet and the perpetuation of attitudes that put democracy itself at risk. If they’ve managed to avoid much of the blame, it’s only because it took decades for us to see the full consequences of their actions, which have emerged more clearly in the generation that they raised in their image. It might well be true, as Douthat wrote, that they trained their children “for service, not just success.” But they also failed miserably.

The long night

Three years ago, a man named Paul Gregory died on Christmas Day. He lived by himself in Desert Hot Springs, California, where he evidently shot himself in his apartment at the age of ninety-five. His death wasn’t widely reported, and it was only this past week that his obituary appeared in the New York Times, which noted of his passing:

Word leaked out slowly. Almost a year later, The Desert Sun, a daily newspaper serving Palm Springs, California, and the Coachella Valley area, published an article that took note of Mr. Gregory’s death, saying that “few people knew about it.” “He wasn’t given a public memorial service and he didn’t receive the kind of appreciations showbiz luminaries usually get,” the newspaper said…When the newspaper’s article appeared, [the Desert Hot Springs Historical Society] had recently given a dinner in Mr. Gregory’s memory for a group of his friends. “His passing was so quiet,” Bruce Fessler, who wrote the article, told the gathering. “No one wrote about him. It’s just one of those awkward moments.”

Yet his life was a remarkable one, and more than worth a full biography. Gregory was a successful film and theater producer who crossed paths over the course of his career with countless famous names. On Broadway, he was the force behind Herman Wouk’s The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial, one of the big dramatic hits of its time, and he produced Laughton’s The Night of the Hunter, which deserves to be ranked among the greatest American movies.

Gregory’s involvement with The Night of the Hunter alone would have merited a mention here, but his death caught my eye for other reasons. As I mentioned here last week, I’ve slowly been reading through Mailer’s Selected Letters, in which both Gregory and Laughton figure prominently. In 1954, Mailer told his friends Charlie and Jill Devlin that he had recently received an offer from Gregory, whom he described as “a kind of front for Charles Laughton,” for the rights to The Naked and the Dead. He continued:

Now, about two weeks ago Gregory called me up for dinner and gave me the treatment. Read Naked five times, he said, loved it, those Marines, what an extraordinary human story of those Marines, etc…What he wants to do, he claims, is have me do an adaptation of Naked, not as a play, but as a dramatized book to be put on like The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial…Anyway, he wants it to be me and only me to do the play version.

The play never got off the ground, but Gregory retained the movie rights to the novel, with an eye to Laughton directing with Robert Mitchum in the lead. Mailer was hugely impressed by Laughton, telling Elsa Lanchester decades later that he had never met “an actor before or since whose mind was so fine and powerful” as her late husband’s. The two men spent a week at Laughton’s hotel in Switzerland going over the book, and Mailer recalled that the experience was “a marvelous brief education in the problems of a movie director.”

In the end, sadly, this version of the movie was never made, and Mailer deeply disliked the film that Gregory eventually produced with director Raoul Walsh. It might all seem like just another footnote to Mailer’s career—but there’s another letter that deserves to be mentioned. At exactly the same time that Mailer was negotiating with Gregory, he wrote an essay titled “The Homosexual Villain,” in which he did the best that he could, given the limitations of his era and his personality, to come to terms with his own homophobia. (Mailer himself never cared for the result, and it’s barely worth reading today even as a curiosity. The closing line gives a good sense of the tone: “Finally, heterosexuals are people too, and the hope of acceptance, tolerance, and sympathy must rest on this mutual appreciation.”) On September 24, 1954, Mailer wrote to the editors of One: The Homosexual Magazine, in which the article was scheduled to appear:

Now, something which you may find somewhat irritating. And I hate like hell to request it, but I think it’s necessary. Perhaps you’ve read in the papers that The Naked and the Dead has been sold to Paul Gregory. It happens to be half-true. He’s in the act of buying it, but the deal has not yet been closed. For this reason I wonder if you could hold off publication for a couple of months? I don’t believe that the publication of this article would actually affect the sale, but it is a possibility, especially since Gregory—shall we put it this way—may conceivably be homosexual.

And while there’s a lot to discuss here, it’s worth emphasizing the casual and utterly gratuitous way in which Mailer—who became friendly years later with Roy Cohn—outed his future business partner by name.

But the letter also inadvertently points to a fascinating and largely unreported aspect of Gregory’s life, which I can do little more than suggest here. Charles Laughton, of course, was gay, as Elsa Lanchester discusses at length in her autobiography. (Gregory appears frequently in this book as well. He evidently paid a thousand dollars to Confidential magazine to kill a story about Laughton’s sexuality, and Lanchester quotes a letter from Gregory in which he accused Henry Fonda, who appeared in The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial, of calling Laughton a “fat, ugly homosexual”—although Laughton told her that Fonda had used an even uglier word.) Their marriage was obviously a complicated one, but it was far from the only such partnership. The actress Mary Martin, best known for her role as Peter Pan, was married for decades to the producer and critic Richard Halliday, whom her biographer David Kaufman describes as “her father, her husband, her best friend, her gay/straight ‘cover,’ and, both literally and figuratively, her manager.” One of Martin’s closest friends was Janet Gaynor, the Academy Award-winning actress who played the lead in the original version of A Star is Born. Gaynor was married for many years to Gilbert Adrian, an openly gay costume designer whose most famous credit was The Wizard of Oz. Gaynor herself was widely believed to be gay or bisexual, and a few years after Adrian’s death, she married a second time—to Paul Gregory. Gaynor and Gregory often traveled with Martin, and they were involved in a horrific taxi accident in San Francisco in 1982, in which Martin’s manager was killed, Gregory broke both legs, Martin fractured two ribs and her pelvis, and Gaynor sustained injuries that led to her death two years later. Gregory remarried, but his second wife passed away shortly afterward, and he appears to have lived quietly on his own until his suicide three years ago. The rest of the world only recently heard about his death. But even if we don’t know the details, it seems clear that there were many stories from his life that we’ll never get to hear at all.

The Bad Pennies, Part 1

For the last couple of months, I’ve been trying to pull together the tangled ends of a story that seems so complicated—and which encompasses so many unlikely personalities—that I doubt that I’ll ever get to the bottom of it, at least not without devoting more time to the project than I currently have to spare. (It really requires a good biography, and maybe two, and in the meantime, I’m just going to throw out a few leads in the hopes that somebody else will follow up.) It centers on a man named William Herbert Sheldon, who was born in 1898 and died in 1977. Sheldon was a psychologist and numismatist who received his doctorate from the University of Chicago and studied under Carl Jung. He’s best known today for his theory of somatotypes, which classified all human beings into degrees of endomorph, mesomorph, or ectomorph, based on their physical proportions. Sheldon argued that an individual’s build was an indication of character and ability, as Ron Rosenbaum wrote over twenty years ago in a fascinating investigative piece for the New York Times:

[Sheldon] believed that every individual harbored within him different degrees of each of the three character components. By using body measurements and ratios derived from nude photographs, Sheldon believed he could assign every individual a three-digit number representing the three components, components that Sheldon believed were inborn—genetic—and remained unwavering determinants of character regardless of transitory weight change. In other words, physique equals destiny.

Sheldon’s work carried obvious overtones of eugenics, even racism, which must have been evident to many observers even at the time. (In the early twenties, Sheldon wrote a paper titled “The Intelligence of Mexican Children,” in which he asserted that “Negro intelligence” comes to a “standstill at about the tenth year.”) And these themes became even more explicit in the writings of his closest collaborator, the anthropologist Earnest A. Hooton. In the fifties, Hooton’s “research” on the physical attributes that were allegedly associated with criminality was treated with guarded respect even by the likes of Martin Gardner, who wrote in his book Fads and Fallacies:

The theory that criminals have characteristic “stigmata”—facial and bodily features which distinguish them from other men—was…revived by Professor Earnest A. Hooton, of the Harvard anthropology faculty. In a study made in the thirties, Dr. Hooton found all kinds of body correlations with certain types of criminality. For example, robbers tend to have heavy beards, diffused pigment in the iris, attached ear lobes, and six other body traits. Hooton must not be regarded as a crank, however—his work is too carefully done to fall into that category—but his conclusions have not been accepted by most of his colleagues, who think his research lacked adequate controls.

Gardner should have known better. Hooton, like Sheldon, was obsessed with dividing up human beings on the basis of their morphological characteristics, as he wrote in the Times in 1936: “Our real purpose should be to segregate and eliminate the unfit, worthless, degenerate and anti-social portion of each racial and ethnic strain in our population, so that we may utilize the substantial merits of the sound majority, and the special and diversified gifts of its superior members.”

Sheldon and Hooton’s work reached its culmination, or nadir, in one of the strangest episodes in the history of anthropology, which Rosenbaum’s article memorably calls “The Great Ivy League Nude Posture Photo Scandal.” For decades, such institutions as Harvard College had photographed incoming freshmen in the nude, supposedly to look for signs of scoliosis and rickets. Sheldon and Hooton took advantage of these existing programs to take nude photos of students, both male and female, at colleges including Harvard, Radcliffe, Princeton, Yale, Wellesley, and Vassar, ostensibly to study posture, but really to gather raw data for their work on somatotypes. The project went on for decades, and Rosenbaum points out that the number of famous alumni who had their pictures taken staggers the imagination: “George Bush, George Pataki, Brandon Tartikoff and Bob Woodward were required to do it at Yale. At Vassar, Meryl Streep; at Mount Holyoke, Wendy Wasserstein; at Wellesley, Hillary Rodham and Diane Sawyer.” After some diligent sleuthing, Rosenbaum determined that most of these photographs were later destroyed, but a collection of negatives survived at the National Anthropological Archives in the Smithsonian, where he was ultimately allowed to view some of them. He writes of the experience:

As I thumbed rapidly through box after box to confirm that the entries described in the Finder’s Aid were actually there, I tried to glance at only the faces. It was a decision that paid off, because it was in them that a crucial difference between the men and the women revealed itself. For the most part, the men looked diffident, oblivious. That’s not surprising considering that men of that era were accustomed to undressing for draft physicals and athletic-squad weigh-ins. But the faces of the women were another story. I was surprised at how many looked deeply unhappy, as if pained at being subjected to this procedure. On the faces of quite a few I saw what looked like grimaces, reflecting pronounced discomfort, perhaps even anger.

And it’s clearly the women who bore the greatest degree of lingering humiliation and fear. Rumors circulated for years that the pictures had been stolen and sold, and such notable figures as Nora Ephron, Sally Quinn, and Judith Martin speak candidly to Rosenbaum of how they were haunted by these memories. (Quinn tells him: “You always thought when you did it that one day they’d come back to haunt you. That twenty-five years later, when your husband was running for president, they’d show up in Penthouse.” For the record, according to Rosenbaum, when the future Hillary Clinton attended Wellesley, undergraduates were allowed to take the pictures “only partly nude.”) Rosenbaum captures the unsavory nature of the entire program in terms that might have been published yesterday:

Suddenly the subjects of Sheldon’s photography leaped into the foreground: the shy girl, the fat girl, the religiously conservative, the victim of inappropriate parental attention…In a culture that already encourages women to scrutinize their bodies critically, the first thing that happens to these women when they arrive at college is an intrusive, uncomfortable, public examination of their nude bodies.

If William Herbert Sheldon’s story had ended there, it would be strange enough, but there’s a lot more to be told. I haven’t even mentioned his work as a numismatist, which led to a stolen penny scandal that rocked the world of coin collecting as deeply as the nude photos did the Ivy League. But the real reason I wanted to talk about him involves one of his protégés, whom Sheldon met while teaching in the fifties at Columbia. His name was Walter H. Breen, who later married the fantasy author Marion Zimmer Bradley—which leads us in turn to one of the darkest episodes in the entire history of science fiction. I’ll be talking more about this tomorrow.

The Men Who Saw Tomorrow, Part 1

If there’s a single theme that runs throughout my book Astounding, it’s the two sides of the editor John W. Campbell. These days, Campbell tends to be associated with highly technical “hard” science fiction with an emphasis on physics and engineering, but he had an equally dominant mystical side, and from the beginning, you often see the same basic impulses deployed in both directions. (After the memory of his career had faded, much of this history was quietly revised, as Algis Burdrys notes in Benchmarks Revisited: “The strong mystical bent displayed among even the coarsest cigar-chewing technists is conveniently overlooked, and Campbell’s subsequent preoccupation with psionics is seen as an inexplicable deviation from a life of hitherto unswerving straight devotion to what we all agree is reasonability.”) As an undergraduate at M.I.T. and Duke, Campbell was drawn successively to Norbert Wiener, the founder of cybernetics, and Joseph Rhine, the psychologist best known for his statistical studies of telepathy. Both professors fed into his fascination with a possible science of the mind, but along strikingly different lines, and he later pursued both dianetics, which he originally saw as a kind of practical cybernetics, and explorations of psychic powers. Much the same holds true of his other great obsession—the problem of foreseeing the future. As I discuss today in an essay in the New York Times, its most famous manifestation was the notion of psychohistory, the fictional science of prediction in Asimov’s Foundation series. But at a time of global uncertainty, it wasn’t the method of forecasting that counted, but the accuracy of the results, and even as Campbell was collaborating with Asimov, his interest in prophecy was taking him to even stranger places.

The vehicle for the editor’s more mystical explorations was Unknown, the landmark fantasy pulp that briefly channeled these inclinations away from the pages of Astounding. (In my book, I argue that the simultaneous existence of these two titles purified science fiction at a crucial moment, and that the entire genre might have evolved in altogether different ways if Campbell had been forced to express all sides of his personality in a single magazine.) As I noted here the other day, in an attempt to attract a wider audience, Campbell removed the cover paintings from Unknown, hoping to make it look like a more mainstream publication. The first issue with the revised design was dated July 1940, and in his editor’s note, Campbell explicitly addressed the “new discoverers” who were reading the magazine for the first time. He grandly asserted that fantasy represented “a completely untrammeled literary medium,” and as an illustration of the kinds of subjects that he intended to explore in his stories, he offered a revealing example:

Until somebody satisfactorily explains away the unquestionable masses of evidence showing that people do have visions of things yet to come, or of things occurring at far-distant points—until someone explains how Nostradamus, the prophet, predicted things centuries before they happened with such minute detail (as to names of people not to be born for half a dozen generations or so!) that no vague “Oh, vague generalities—things are always happening that can be twisted to fit!” can possibly explain them away—until the time those are docketed and labeled and nearly filed—they belong to The Unknown.

It was Campbell’s first mention in print of Nostradamus, the sixteenth-century French prophet, but it wouldn’t be the last. A few months later, Campbell alluded in another editorial to the Moberly-Jourdain incident, in which two women claimed to have traveled over a century back in time on a visit to the Palace of Versailles. The editor continued: “If it happens one way—how about the other? How about someone slipping from the past to the future? It is known—and don’t condemn till you’ve read a fair analysis of the old man’s works—that Nostradamus, the famous French prophet, did not guess at what might happen; he recorded what did happen—before it happened. His accuracy of prophecy runs considerably better, actually, than the United States government crop forecasts, in percentage, and the latter are certainly used as a basis for business.” Campbell then drew a revealing connection between Nostradamus and the war in Europe:

Incidentally, to avoid disappointment, Nostradamus did not go into much detail about this period. He was writing several hundred years ago, for people of that time—and principally for Parisians. He predicted in some detail the French Revolution, predicted several destructions of Paris—which have come off on schedule, to date—and did not predict destruction of Paris for 1940. He did, however, for 1999—by a “rain of fire from the East.” Presumably he didn’t have any adequate terms for airplane bombs, so that may mean thermite incendiaries. But the present period, too many centuries from his own times, would be of minor interest to him, and details are sketchy. The prophecy goes up to about the thirty-fifth century.

And the timing was highly significant. Earlier that year, Campbell had published the nonfiction piece “The Science of Whithering” by L. Sprague de Camp in Astounding, shortly after German troops marched into Paris. De Camp’s article, which discussed the work of such cyclical historians as Spengler and Toynbee, represented the academic or scientific approach the problem of forecasting, and it would soon find its fictional expression in such stories as Jack Williamson’s “Breakdown” and Asimov’s “Foundation.” As usual, however, Campbell was playing both sides, and he was about to pursue a parallel train of thought in Unknown that has largely been forgotten. Instead of attempting to explain Nostradamus in rational terms, Campbell ventured a theory that was even more fantastic than the idea of clairvoyance:

Occasionally a man—vanishes…And somehow, he falls into another time. Sometimes future—sometimes past. And sometimes he comes back, sometimes he doesn’t. If he does come back, there’d be a tendency, and a smart one, to shut up; it’s mighty hard to prove. Of course, if he’s a scholarly gentlemen, he might spend his unintentional sojourn in the future reading histories of his beloved native land. Then, of course, he ought to be pretty accurate at predicting revolutions and destruction of cities. Even be able to name inconsequential details, as Nostradamus did.

To some extent, this might have been just a game that he was playing for his readers—but not completely. Campbell’s interest in Nostradamus was very real, and just as he had used Williamson and Asimov to explore psychohistory, he deployed another immensely talented surrogate to look into the problem of prophecy. His name was Anthony Boucher. I’ll be exploring this in greater detail tomorrow.

Note: Please join me today at 12:00pm ET for a Twitter AMA to celebrate the release of the fantastic new horror anthology Terror at the Crossroads, which includes my short story “Cryptids.”

Fire and Fury

I’ve been thinking a lot recently about Brian De Palma’s horror movie The Fury, which celebrated its fortieth anniversary earlier this year. More specifically, I’ve been thinking about Pauline Kael’s review, which is one of the pieces included in her enormous collection For Keeps. I’ve read that book endlessly for two decades now, and as a result, The Fury is one of those films from the late seventies—like Philip Kaufman’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers—that endure in my memory mostly as a few paragraphs of Kael’s prose. In particular, I often find myself remembering these lines:

De Palma is the reverse side of the coin from Spielberg. Close Encounters gives us the comedy of hope. The Fury is the comedy of cruelly dashed hope. With Spielberg, what happens is so much better than you dared hope that you have to laugh; with De Palma, it’s so much worse than you feared that you have to laugh.

That sums up how I feel about a lot of things these days, when everything is consistently worse than I could have imagined, although laughter usually feels very far away. (Another line from Kael inadvertently points to the danger of identifying ourselves with our political heroes: “De Palma builds up our identification with the very characters who will be destroyed, or become destroyers, and some people identified so strongly with Carrie that they couldn’t laugh—they felt hurt and betrayed.”) And her description of one pivotal scene, which appears in her review of Dressed to Kill, gets closer than just about anything else to my memories of the last presidential election: “There’s nothing here to match the floating, poetic horror of the slowed-down sequence in which Amy Irving and Carrie Snodgress are running to freedom: it’s as if each of them and each of the other people on the street were in a different time frame, and Carrie Snodgress’s face is full of happiness just as she’s flung over the hood of a car.”

The Fury seems to have been largely forgotten by mainstream audiences, but references to it pop up in works ranging from Looper to Stranger Things, and I suspect that it might be due for a reappraisal. It’s about two teenagers, a boy and a girl, who have never met, but who share a psychic connection. As Kael notes, they’re “superior beings” who might have been prophets or healers in an earlier age, but now they’ve been targeted by our “corrupt government…which seeks to use them for espionage, as secret weapons.” Reading this now, I’m slightly reminded of our current administration’s unapologetic willingness to use vulnerable families and children as political pawns, but that isn’t really the point. What interests me more is how De Palma’s love of violent imagery undercuts the whole moral arc of the movie. I might call this a problem, except that it isn’t—it’s a recurrent feature of his work that resonated uneasily with viewers who were struggling to integrate the specter of institutionalized violence into their everyday lives. (In a later essay, Kael wrote of acquaintances who resisted such movies because of its association with the “guilty mess” of the recently concluded war: “There’s a righteousness in their tone when they say they don’t like violence; I get the feeling that I’m being told that my urging them to see The Fury means that I’ll be responsible if there’s another Vietnam.”) And it’s especially striking in this movie, which for much of its length is supposedly about an attempt to escape this cycle of vengeance. Of the two psychic teens, Robyn, played by Andrew Stevens, eventually succumbs to it, while Gillian, played by Amy Irving, fights it for as long as she can. As Kael explains: “Both Gillian and Robyn have the power to zap people with their minds. Gillian is trying to cling to her sanity—she doesn’t want to hurt anyone. And, knowing that her power is out of her conscious control, she’s terrified of her own secret rages.”

And it’s hard for me to read this passage now without connecting it to the ongoing discussion over women’s anger, in which the word “fury” occurs with surprising frequency. Here’s the journalist Rebecca Traister writing in the New York Times, in an essay adapted from her bestselling book Good and Mad:

Fury was a tool to be marshaled by men like Judge Kavanaugh and Senator Graham, in defense of their own claims to political, legal, public power. Fury was a weapon that had not been made available to the woman who had reason to question those claims…Most of the time, female anger is discouraged, repressed, ignored, swallowed. Or transformed into something more palatable, and less recognizable as fury—something like tears. When women are truly livid, they often weep…This political moment has provoked a period in which more and more women have been in no mood to dress their fury up as anything other than raw and burning rage.

Traister’s article was headlined: “Fury is a Political Weapon. And Women Need to Wield It.” And if you were so inclined, you could take The Fury as an extended metaphor for the issue that Casey Cep raises in her recent roundup of books on the subject in The New Yorker: “A major problem with anger is that some people are allowed to express it while others are not.” In the film, Gillian spends most of the movie resisting her violent urges, while her male psychic twin gives into them, and the climax—which is the only scene that most viewers remember—hinges on her embrace of the rage that Robyn passed to her at the moment of his death.

This brings us to Childress, the villain played by John Cassavetes, whose demise Kael hyperbolically describes as “the greatest finish for any villain ever.” A few paragraphs earlier, Kael writes of this scene:

This is where De Palma shows his evil grin, because we are implicated in this murderousness: we want it, just as we wanted to see the bitchy Chris get hers in Carrie. Cassavetes is an ideal villain (as he was in Rosemary’s Baby)—sullenly indifferent to anything but his own interests. He’s so right for Childress that one regrets that there wasn’t a real writer around to match his gloomy, viscous nastiness.

“Gloomy, viscous nastiness” might ring a bell today, and Childress’s death—Gillian literally blows him up with her mind—feels like the embodiment of our impulses for punishment, revenge, and retribution. It’s stunning how quickly the movie discards Gillian’s entire character arc for the sake of this moment, but what makes the ending truly memorable is what happens next, which is nothing. Childress explodes, and the film just ends, because it has nothing left to show us. That works well enough in a movie, but in real life, we have to face the problem of what Brittney Cooper, whose new book explicitly calls rage a superpower, sums up as “what kind of world we want to see, not just what kind of things we want to get rid of.” In her article in The New Yorker, Cep refers to the philosopher and classicist Martha Nussbaum’s treatment of the Furies themselves, who are transformed at the end of the Oresteia into the Eumenides, “beautiful creatures that serve justice rather than pursue cruelty.” It isn’t clear how this transformation takes place, and De Palma, typically, sidesteps it entirely. But if we can’t imagine anything beyond cathartic vengeance, we’re left with an ending closer to what Kael writes of Dressed to Kill: “The spell isn’t broken and [De Palma] doesn’t fully resolve our fear. He’s saying that even after the horror has been explained, it stays with you—the nightmare never ends.”

The chosen ones

In his recent New Yorker profile of Mark Zuckerberg, Evan Osnos quotes one of the Facebook founder’s close friends: “I think Mark has always seen himself as a man of history, someone who is destined to be great, and I mean that in the broadest sense of the term.” Zuckerberg feels “a teleological frame of feeling almost chosen,” and in his case, it happened to be correct. Yet this tells us almost nothing abut Zuckerberg himself, because I can safely say that most other undergraduates at Harvard feel the same way. A writer for The Simpsons once claimed that the show had so many presidential jokes—like the one about Grover Cleveland spanking Grandpa “on two non-consecutive occasions”—because most of the writers secretly once thought that they would be president themselves, and he had a point. It’s very hard to do anything interesting in life without the certainty that you’re somehow one of the chosen ones, even if your estimation of yourself turns out to be wildly off the mark. (When I was in my twenties, my favorite point of comparison was Napoleon, while Zuckerberg seems to be more fond of Augustus: “You have all these good and bad and complex figures. I think Augustus is one of the most fascinating. Basically, through a really harsh approach, he established two hundred years of world peace.”) This kind of conviction is necessary for success, although hardly sufficient. The first human beings to walk on Mars may have already been born. Deep down, they know it, and this knowledge will determine their decisions for the rest of their lives. Of course, thousands of others “know” it, too. And just a few of them will turn out to be right.

One of my persistent themes on this blog is how we tend to confuse talent with luck, or, more generally, to underestimate the role that chance plays in success or failure. I never tire of quoting the economist Daniel Kahneman, who in Thinking Fast and Slow shares what he calls his favorite equation:

Success = Talent + Luck

Great Success = A little more talent + A lot of luck

The truth of this statement seems incontestable. Yet we’re all reluctant to acknowledge its power in our own lives, and this tendency only increases as the roles played by luck and privilege assume a greater importance. This week has been bracketed by news stories about two men who embody this attitude at its most extreme. On the one hand, you have Brett Kavanaugh, a Yale legacy student who seems unable to recognize that his drinking and his professional success weren’t mutually exclusive, but closer to the opposite. He occupied a cultural and social stratum that gave him the chance to screw up repeatedly without lasting consequences, and we’re about to learn how far that privilege truly extends. On the other hand, you have yesterday’s New York Times exposé of Donald Trump, who took hundreds of millions of dollars from his father’s real estate empire—often in the form of bailouts for his own failed investments—while constantly describing himself as a self-made billionaire. This is hardly surprising, but it’s still striking to see the extent to which Fred Trump played along with his son’s story. He understood the value of that myth.

This gets at an important point about privilege, no matter which form it takes. We have a way of visualizing these matters in spatial terms—”upper class,” “lower class,” “class pyramid,” “rising,” “falling,” or “stratum” in the sense that I used it above. But true privilege isn’t spatial, but temporal. It unfolds over time, by giving its beneficiaries more opportunities to fail and recover, when those living at the edge might not be able to come back from the slightest misstep. We like to say that a privileged person is someone who was born on third base and thinks he hit a triple, but it’s more like being granted unlimited turns at bat. Kavanaugh provides a vivid reminder, in case we needed one, that a man who fits a certain profile has the freedom to make all kinds of mistakes, the smallest of which would be fatal for someone who didn’t look like he did. And this doesn’t just apply to drunken misbehavior, criminal or otherwise, but even to the legitimate failures that are necessary for the vast majority of us to achieve real success. When you come from the right background, it’s easier to survive for long enough to benefit from the effects of luck, which influences the way that we talk about failure itself. Silicon Valley speaks of “failing faster,” which only makes sense when the price of failure is humiliation or the loss of investment capital, not falling permanently out of the middle class. And as I’ve noted before, Pixar’s creative philosophy, which Andrew Stanton described as a process in which “the films still suck for three out of the four years it takes to make them,” is only practicable for filmmakers who look and sound like their counterparts at the top, which grants them the necessary creative freedom to fail repeatedly—a luxury that women are rarely granted.

This may all come across as unbelievably depressing, but there’s a silver lining, and it took me years to figure it out. The odds of succeeding in any creative field—which includes nearly everything in which the standard career path isn’t clearly marked—are minuscule. Few who try will ever make it, even if they have “a teleological frame of feeling almost chosen.” This isn’t due to a lack of drive or talent, but of time and second chances. When you combine the absence of any straightforward instructions with the crucial role played by luck, you get a process in which repeated failure over a long period is almost inevitable. Those who drop out don’t suffer from weak nerves, but from the fact that they’ve used up all of their extra lives. Privilege allows you to stay in the game for long enough for the odds to turn in your favor, and if you’ve got it, you may as well use it. (An Ivy League education doesn’t guarantee success, but it drastically increases your ability to stick around in the middle class in the meantime.) In its absence, you can find strategies of minimizing risk in small ways while increasing it on the highest levels, which just another word for becoming a bohemian. And the big takeaway here is that since the probability of success is already so low, you may as well do exactly what you want. It can be tempting to tailor your work to the market, reasoning that it will increase your chances ever so slightly, but in reality, the difference is infinitesimal. An objective observer would conclude that you’re not going to make it either way, and even if you do, it will take about the same amount of time to succeed by selling out as it would by staying true to yourself. You should still do everything that you can to make the odds more favorable, but if you’re probably going to fail anyway, you might as well do it on your own terms. And that’s the only choice that matters.

The Order of St. John’s

When I think back on my personal experience with the great books, as I did here the other day, I have to start with the six weeks that I spent as a high school junior at St. John’s College in Annapolis, Maryland. As I’ve discussed in greater detail before, I had applied to the Telluride Associate Summer Program on the advice of my guidance counselor. It was an impulsive decision, but I was accepted, and I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to call it one of the three or four most significant turning points in my entire life. I was more than primed for a program like this—I had just bought my own set of the Great Books of the Western World at a church book sale—and I left with my head full of the values embodied by the college, which still structures its curriculum around a similar notion of the Western Canon. Throughout the summer, I attended seminars with seventeen other bright teenagers, and as we worked our way from Plato’s Cratylus through Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations, it all seemed somehow normal. I more or less assumed that this was how college would be, which wasn’t entirely true, although I did my best to replicate the experience. Looking back, in fact, I suspect that my time at St. John’s was more responsible than any other factor for allowing me to attend the college of my choice, and it certainly played a role in my decision to major in classics. But it’s only now that I can fully appreciate how much privilege went into each stage in that process. It came down to a series of choices, which I was able to make freely, and while I don’t think I always acted correctly, I’m amazed at how lucky I was, and how the elements of a liberal education itself managed to obscure that crucial point.

I’ve been thinking about this recently because of an article by Frank Bruni in the New York Times, who paid a visit to the sister campus of St. John’s College in Santa Fe. He opens with a description that certainly would have appealed to my adolescent self, although probably not to most other teenagers:

Have I got a college for you. For your first two years, your regimen includes ancient Greek. And I do mean Greek, the language, not Greece, the civilization, though you’ll also hang with Aristotle, Aeschylus, Thucydides and the rest of the gang. There’s no choice in the matter. There’s little choice, period…You have no major, only “the program,” an exploration of the Western canon that was implemented in 1937 and has barely changed…It’s an increasingly exotic and important holdout against so many developments in higher education—the stress on vocational training, the treatment of students as fickle consumers, the elevation of individualism over a shared heritage—that have gone too far. It’s a necessary tug back in the other direction.

More than twenty years after I spent the summer there, the basic pitch for the college doesn’t seem to have changed. Its fans still draw a pointed comparison between the curriculum at St. John’s and the supposedly more “consumerist” approach of most undergraduate programs, and it tends to define itself in sharp contrast to the touchy-feely world around it. “Let your collegiate peers elsewhere design their own majors and frolic with Kerouac,” Bruni writes. “For you it’s Kant.”

Yet it isn’t hard to turn this argument on its head, or to recognize that there’s a real sense in which St. John’s might be one of the most individualistic and consumerist colleges in the entire country. (The article itself is headlined “The Most Contrarian College in America,” while Bruni writes that he was drawn to it “out of respect for its orneriness.” And a school for ornery contrarians sounds pretty individualistic to me.) We can start with the obvious point that “the stress on vocational training” at other colleges is the result of economic anxiety at a time of rising tuitions and crippling student loans. There’s tremendous pressure to turn students away from the humanities, and it isn’t completely unjustified. The ability to major in classics or philosophy reflects a kind of privilege in itself, at least in the form of the absence of some of those pressures, and it isn’t always about money. For better or worse, reading the great books is just about the most individualistic gesture imaginable, and its supposed benefits—what the dean of the Santa Fe campus characterizes as the creation of “a more thoughtful, reflective, self-possessed and authentic citizen, lover, partner, parent and member of the global economy”—are obsessively focused on the self. The students at St. John’s may not have the chance to shop around for classes once they get there, but they made a vastly more important choice as a consumer long before they even arrived. A choice of college amounts to a lot of things, but it’s certainly an act with financial consequences. In many cases, it’s the largest purchase that any of us will ever make. The option of spending one’s college years reading Hobbes and Spinoza at considerable cost doesn’t even factor into the practical or economic universe of most families, and it would be ridiculous to claim otherwise.

In other words, every student at St. John’s exercised his or her power in the academic marketplace when it mattered most. By comparison, the ability to tailor one’s class schedule seems like a fairly minor form of consumerism—which doesn’t detract from the quality of the product, which is excellent, as it should be at such prices. (Bruni notes approvingly that the college recently cut its annual tuition from $52,000 to $35,000, which I applaud, although it doesn’t change my underlying point.) But it’s difficult to separate the value of such an education from the existing qualities required for a high schooler to choose it in the first place. It’s hard for me to imagine a freshman at St. John’s who wasn’t intelligent, motivated, and individualistic, none of which would suffer from four years of immersion in the classics. They’re already lucky, which is a lesson that the great books won’t teach on their own. The Great Conversation tends to take place within a circle of authors who have been chosen for their resemblance to one another, or for how well they fit into a cultural narrative imposed on them after the fact, as Robert Maynard Hutchins writes in the introduction to Great Books of the Western World: “The set is almost self-selected, in the sense that one book leads to another, amplifying, modifying, or contradicting it.” And that’s fine. But it means that you rarely see these authors marveling over their own special status, which they take for granted. For a canon that consists entirely of books written by white men, there’s remarkably little discussion of privilege, because they live in it like fish in water—which is as good an argument for diversity as any I can imagine. The students at St. John’s may ask these hard questions about themselves, but if they do, it’s despite what they read, not because of it. Believe me, I should know.

The end of flexibility

A few days ago, I picked up my old paperback copy of Steps to an Ecology of Mind, which collects the major papers of the anthropologist and cyberneticist Gregory Bateson. I’ve been browsing through this dense little volume since I was in my teens, but I’ve never managed to work through it all from beginning to end, and I turned to it recently out of a vague instinct that it was somehow what I needed. (Among other things, I’m hoping to put together a collection of my short stories, and I’m starting to see that many of Bateson’s ideas are relevant to the themes that I’ve explored as a science fiction writer.) I owe my introduction to his work, as with so many other authors, to Stewart Brand of The Whole Earth Catalog, who advised in one edition:

[Bateson] wandered thornily in and out of various disciplines—biology, ethnology, linguistics, epistemology, psychotherapy—and left each of them altered with his passage. Steps to an Ecology of Mind chronicles that journey…In recommending the book I’ve learned to suggest that it be read backwards. Read the broad analyses of mind and ecology at the end of the book and then work back to see where the premises come from.

This always seemed reasonable to me, so when I returned to it last week, I flipped immediately to the final paper, “Ecology and Flexibility in Urban Civilization,” which was first presented in 1970. I must have read it at some point—I’ve quoted from it several times on this blog before—but as I looked over it again, I found that it suddenly seemed remarkably urgent. As I had suspected, it was exactly what I needed to read right now. And its message is far from reassuring.

Bateson’s central point, which seems hard to deny, revolves around the concept of flexibility, or “uncommitted potentiality for change,” which he identifies as a fundamental quality of any healthy civilization. In order to survive, a society has to be able to evolve in response to changing conditions, to the point of rethinking even its most basic values and assumptions. Bateson proposes that any kind of planning for the future include a budget for flexibility itself, which is what enables the system to change in response to pressures that can’t be anticipated in advance. He uses the analogy of an acrobat who moves his arms between different positions of temporary instability in order to remain on the wire, and he notes that a viable civilization organizes itself in ways that allow it to draw on such reserves of flexibility when needed. (One of his prescriptions, incidentally, serves as a powerful argument for diversity as a positive good in its own right: “There shall be diversity in the civilization, not only to accommodate the genetic and experiential diversity of persons, but also to provide the flexibility and ‘preadaptation’ necessary for unpredictable change.”) The trouble is that a system tends to eat up its own flexibility whenever a single variable becomes inflexible, or “uptight,” compared to the rest:

Because the variables are interlinked, to be uptight in respect to one variable commonly means that other variables cannot be changed without pushing the uptight variable. The loss of flexibility spreads throughout the system. In extreme cases, the system will only accept those changes which change the tolerance limits for the uptight variable. For example, an overpopulated society looks for those changes (increased food, new roads, more houses, etc.) which will make the pathological and pathogenic conditions of overpopulation more comfortable. But these ad hoc changes are precisely those which in longer time can lead to more fundamental ecological pathology.

When I consider these lines now, it’s hard for me not to feel deeply unsettled. Writing in the early seventies, Bateson saw overpopulation as the most dangerous source of stress in the global system, and these days, we’re more likely to speak of global warming, resource depletion, and income inequality. Change a few phrases here and there, however, and the situation seems largely the same: “The pathologies of our time may broadly be said to be the accumulated results of this process—the eating up of flexibility in response to stresses of one sort or another…and the refusal to bear with those byproducts of stress…which are the age-old correctives.” Bateson observes, crucially, that the inflexible variables don’t need to be fundamental in themselves—they just need to resist change long enough to become a habit. Once we find it impossible to imagine life without fossil fuels, for example, we become willing to condone all kinds of other disruptions to keep that one hard-programmed variable in place. A civilization naturally tends to expand into any available pocket of flexibility, blowing through the budget that it should have been holding in reserve. The result is a society structured along lines that are manifestly rigid, irrational, indefensible, and seemingly unchangeable. As Bateson puts it grimly:

Civilizations have risen and fallen. A new technology for the exploitation of nature or a new technique for the exploitation of other men permits the rise of a civilization. But each civilization, as it reaches the limits of what can be exploited in that particular way, must eventually fall. The new invention gives elbow room or flexibility, but the using up of that flexibility is death.