Posts Tagged ‘Frederik Pohl’

Ben Bova (1932-2020)

Earlier this month, the legendary author and editor Ben Bova passed away in Florida. Bova famously took over Analog after the death of John W. Campbell, and he was the crucial figure in a transition that managed to honor the magazine’s tradition of hard science fiction while pushing into stranger, less predictable territory. By publishing stories like “The Gold at the Starbow’s End” by Frederik Pohl, “Hero” by Joe Haldeman, and “Ender’s Game” by Orson Scott Card, as well as important work by such authors as George R.R. Martin and Vonda N. McIntyre, Bova did more than anyone else to usher the Campbellian mode into the new era, and the result still embodies the genre’s possibilities for countless fans. I never met Bova in person, and I only had the chance to interview him once over the phone, but I was pleased to help out very slightly with his obituary in the New York Times. It’s a tribute that he richly deserved, and I hope that his example will endure well into the next generation of editors and writers.

The invisible library

Over the last week, three significant events occurred in the timeline of my book Astounding. The page proofs—the typeset text to which the author can still make minor changes and corrections—were due back at my publisher on Wednesday. Yesterday, I received a boxful of uncorrected advance copies, which look great. And I got paid. This last point might not seem worth mentioning, but it’s an aspect of the process that doesn’t get the attention that it deserves. An advance payment for a book, which is often the only money that a writer ever sees, is usually delivered in three installments. (The breakdown depends on the terms of the contract, but it’s roughly divided into thirds, although the first chunk is generally a little larger than the others, and the middle one tends to be the smallest.) One piece is paid on signing; another on acceptance of the manuscript; and the last on publication. In practice, the payments can get held up for one reason or another, and in my case, nearly two and a half years passed between the first installment and the second. That’s a long time to stretch it out. And it points to one of the challenges of the publishing industry, which is that it’s survivable only by writers who have either an alternative source of income or a robust support structure. This naturally limits the kinds of voices and the range of subjects that it can accommodate. I don’t think that I could have written this book in under three years if I had been working a regular job, and the fact that I managed to pull it off at all was thanks to luck, good timing, and a very patient spouse.

But it also provided me with fresh insight into one of my great unanswered questions about this project, which was why no one had ever done it before. A biography of John W. Campbell seemed like such an obvious and necessary book that I was amazed to realize that it didn’t exist, and it was that moment of realization that inspired this whole enterprise. If anything like it had been attempted in the past, even in an obscure academic publication, I don’t think I would have tackled it in the first place. One explanation for its absence is that the best time for such a book would have been in the late seventies, when such writers as Isaac Asimov and Frederik Pohl were publishing their memoirs, and by the time various obstacles had been sorted out, its moment had come and gone. And it’s also true that Campbell’s life presents particular challenges that might dissuade potential biographers. It would have been a tough project for anyone, and one of my advantages may have been that I underestimated the difficulties that it would present. But the simple fact, as I’ve come to appreciate, is that the odds are against any book seeing the light of day. This one hinged on a combination of factors so unlikely that I have trouble believing it myself, and if just one of those pieces had failed to fall into place, it never would have happened. Maybe someone else would have tried again a decade from now, but I’m not sure. If it seems inevitable to me now, that’s another reason to reflect on the many books that have yet to be written. (Even within the field of science fiction, there are staggering omissions. There’s no biography or study of Leigh Brackett, for instance, and I strongly encourage someone else to pitch it before I do.) This book exists, which is a miracle in itself. But for every book that sees print, there’s an invisible library of unwritten—and equally worthy—books behind it.

The mogul empire

Earlier this month, the news sites DNAinfo and Gothamist were abruptly closed by their owner, the billionaire Joe Ricketts, after their staff voted to join the Writers Guild of America East. Ricketts, who founded Ameritrade and controls the Chicago Cubs, took down the home pages of both publications—including, temporarily, their archives, which made it hard for their suddenly jobless reporters to even access their own clips—and replaced them with a letter stating that the sites hadn’t been successful enough “to support the tremendous effort and expense needed to produce the type of journalism on which the company was founded.” Back in September, however, Ricketts wrote a blog post, “Why I’m Against Unions At Businesses I Create,” that cast his decision in a somewhat different light:

In my opinion, the essential esprit de corps that every successful company needs can’t exist when employees and ownership see themselves as being on opposite ends of a seesaw. Everyone at a company—owners and employees alike—need to be sitting on the same end of the seesaw because the world is sitting on the other end. I believe unions promote a corrosive us-against-them dynamic that destroys the esprit de corps businesses need to succeed. And that corrosive dynamic makes no sense in my mind where an entrepreneur is staking his capital on a business that is providing jobs and promoting innovation.

Of course, his response to his newly unionized employees, who hadn’t even made any demands yet, wasn’t exactly conducive to esprit de corps, either. As a headline in the opinion section of the New York Times put it, Ricketts, who supported Donald Trump after spending millions of dollars in an unsuccessful bid to derail his candidacy, seems to have closed his own businesses entirely out of spite.

And this isn’t just a story about unionization, but the unpleasant flip side of a daydream to which many of us secretly cling about journalism—the notion that in the face of falling circulation and a shaky business model, its salvation lies with philanthropic or ambitious billionaires. We’ve seen this work fairly well with Jeff Bezos and the Washington Post, but other recent examples don’t exactly inspire confidence. In 2012, The New Republic was acquired by Chris Hughes of Facebook, who cut its annual number of print issues in half and revamped it as a “vertically integrated digital-media company,” leading to the resignations of editors Franklin Foer and Leon Wieseltier. (Foer rebounded with a book pointedly titled World Without Mind: The Existential Threat of Big Tech, while Wieseltier has suffered from unrelated troubles of his own.) Go a little further back, and you have the acquisition of the New York Observer by none other than Jared Kushner, which went about as well as you would expect. As Rich Cohen writes in Vanity Fair:

The Observer was a hybrid—tabloid heart, broadsheet brain. A funny man in a serious mood, a serious man with a sense of humor…Kushner either did not get this or did not care. Millennials have a thing about broadsheets. They’ve grown up reading on phones, that smooth path of entry. They can’t stand unwieldiness—following a piece from front page to jump, and all that folding, and the ink stains your fingers.

Kushner took the Observer to tabloid size, discontinued its print edition, and even fired Rex Reed, turning the paper into a ghost town. He and Hughes are at opposite ends of the political spectrum, but they both seized a vulnerable publication, tried to turn it into something that it wasn’t, and all but destroyed it. Ricketts, who shut down Gothamist a mere eight months after buying it, simply took that process to its logical conclusion. And these cases all point to the risk involved when the future of a media enterprise lies in the hands of an outside benefactor who sees no reason not to dismantle it as impulsively as he bought it in the first place.

Obviously, there are countless examples of media companies that fared poorly after an acquisition, but I’ve been thinking recently about one particular case, in which The New Republic also figures prominently. The American News Company was the distribution firm and wholesaler on which many magazines once depended to get on newsstands, and its collapse in 1957 is widely seen as an “extinction event” that caused a meltdown of the market for short science fiction. (For additional details, see this post, particularly the comments.) Here’s how Frederik Pohl describes it in The Way the Future Was:

ANC was big, mighty, and old. It had been around so long that over the years it had acquired all sorts of valuable property. Land. Buildings. Restaurants. Franchises. Items of considerable cash value, acquired when time was young and everything was cheap, and still carried on their books at the pitiful acquisition costs of 1890 or 1910. A stock operator took note of all this and observed that if you bought up all the outstanding stock in ANC (a publicly held corporation) at prevailing prices, you would have acquired an awful lot of valuable real estate at, really, only a few cents on the dollar. It was as profitable as buying dollar bills for fifty cents each…So he did. He bought a controlling interest and liquidated the company.

The truth is slightly more complicated. The American News Company had been on the decline for years, with the departure of such major clients as Time, Look, and Newsweek, and its acquirer wasn’t a “stock operator,” but Henry Garfinkle, the wealthy owner of a newsstand chain called the Union News Corporation. There were obvious possibilities for vertical integration, and for the first year or so, he seems to have made a real effort to run the combined company.

Unfortunately, in the face of falling sales for the industry as a whole, his efforts took the form of a crackdown on small niche magazines that were having trouble sustaining large audiences, in a cycle that seems awfully familiar. (As one contemporary account stated: “The American News Company found that the newsstand demand for some of the more intellectual magazines like The New Republic, Commonweal, Wisdom, and Faith was so small that it was profitless to carry them.”) His brutal tactics alienated publishers, including Dell, its largest client, which filed a lawsuit for restraint of trade. More magazines left, including The New Yorker and Vogue, which, combined with an ongoing antitrust investigation, was what finally led Garfinkle to cut his losses and liquidate. Yet there isn’t much doubt that Garfinkle’s approach played a role in driving his clients away, and he had plenty of help on that front. He had started his empire with a single newsstand that he bought in his teens with a loan from a generous patron, and when he took control of the American News Company, the transaction was masterminded by his general counsel, who had joined the firm the year before. As one author describes this attorney’s “hardball legal tactics”:

[He] later claimed to have engineered Garfinkle’s successful coup. At the publicly held company’s annual meeting in March 1955, Garfinkle headed a dissident group that eventually forced the management to resign. This bold move allowed Garfinkle to gain control of the ninety-one-year-old company, which called itself the world’s oldest magazine wholesaler. Garfinkel revamped the ailing company, renamed it Ancorp National Services, Inc., and gained a near stranglehold on the distribution of newspapers and magazines in the Northeast.

This passage appears in Thomas Maier’s biography Newhouse. The benefactor who gave Garfinkle his start was Sam Newhouse, Sr., and the general counsel who oversaw the takeover—and remained at the company throughout all that followed—was none other than Roy Cohn. I’m not saying that Cohn, on top of everything else, also killed the science fiction market. But if history has taught us one thing, it’s that publications should watch out when a buyer like this comes calling.

The millennial bug

“The myth that underemployed, poorly housed young people are joyfully engaged in a project of creative destruction misrepresents our economic reality,” Laura Marsh wrote earlier this week in The New Republic. Marsh was lashing out, and to some extent with good reason, at the way in which the media likes to portray millennials as cultural rebels. She points out that many of the lifestyle trends that have been observed in people under thirty-five—communal living, car sharing, a preference for “accessing” content rather than paying for individual movies or albums, even a dislike of paper napkins—have less to do with free choice than with simple economic considerations. We’re living in a relatively healthy economy that has been rough on young workers and recent graduates, and millennials, on average, have lower standards of living than their parents did at the same age. It’s no surprise, then, that the many of the social patterns that they exhibit would be shaped by these constraints. What frustrates Marsh is the idea that millennials are voluntarily electing to eliminate certain elements from their lives, like vacations or steady jobs, rather than being forced into those choices by a dearth of opportunity. Headlines tell us that “Millennials are killing the X industry,” when a more truthful version would be “Millennials are locked out of the X industry.” As Marsh concludes: “There’s nothing like being told precarity is actually your cool lifestyle choice.”

I’m not going to dispute this argument, which I think is a pretty reasonable one. But I’d also like to raise the possibility that Marsh and her targets are both right. Let’s perform a quick thought experiment, and try to envision a millennial lifestyle—at least of the kind that is likely to influence the culture in a meaningful way—that isn’t in some way connected to economic factors. The fact is, we can’t. For better or worse, every youth subculture, particularly of the sort that we like to romanticize, emerges from what Marsh calls precarity, or the condition of living on the edge. Sometimes it’s by choice, sometimes it isn’t, and it can be hard to tell the difference. Elsewhere, I’ve described the bohemian lifestyle as a body of pragmatic solutions to the problem of trying to make art for a living. A book like Tropic of Cancer is a manual of survival, and everything that seems distinctive about its era, from the gatherings in coffee shops to the drug and alcohol abuse, can be seen in that light. You could say much the same of the counterculture of the sixties and seventies: being a hippie is a surprisingly practical pursuit, with a limited set of possible approaches, if you’re determined to prioritize certain values. In time, it becomes a style or a statement, but only after a few members of that generation have produced important works of art. And because the artists fascinate us, we look at their lives for clues of how they emerged, while forgetting how much of it was imposed by financial realities.

Take the Futurians, for example, whom I can discuss at length because I’ve been thinking about them a lot. They were a circle of science fiction fans who gathered around the charismatic figure of Donald A. Wollheim in the late thirties, and they can seem impossibly remote from us—more so, I suspect, than the Lost Generation of the decade before. But when you look at them more closely, you start to see a lot of familiar patterns. They practiced a kind of communal living; they were active on the social media of their time, namely the fanzines, in which they engaged in fierce ideological disputes; and many of them were drawn to a form of socialism that even a supporter of Bernie Sanders might find extreme. Most were unemployed, trying to scratch out a living as freelance writers and consistently failing to break into the professional magazines. And they were defined, on a practical level, by their lack of money. Fred Pohl says that his favorite activity was to walk for miles with a friend to a lunch counter in Times Square to buy a cheap sandwich and cup of coffee, and turn around to trudge home again, which would kill most of an afternoon. James Blish and Virginia Kidd lived for months on a bag of rice. Whenever someone got a job, he or she left the group. The rest continued to scrape by as best they could. And the result was a genuine counterculture that arose at the point where the Great Depression merged with the solutions that a few gifted but underemployed writers developed to hang in there for as long as possible.

This probably isn’t much consolation to a recent graduate in his or her twenties whose only ambition at the moment is to pay the rent. But that’s true of previous generations as well. We tend to remember a handful of exceptional individuals, particularly those who produced defining works of art, and we forget the others who were just trying to get by. As the decades pass, I suspect that the same process will occur with the millennials, and that the narrative of who they were will have less to do with Marsh’s thoughtful essay than with the think pieces about how twentysomethings are killing relationships, or car culture, or the napkin industry. And it won’t be wrong. Invariably, at any point in history, the majority of young people don’t have many resources—and that’s especially true for those who use their twenties to try to tell stories about themselves. Where the periods differ is in the details, which is why the boring fact of precarity tends to fade into the background while the external manifestations get our attention. This is already happening now, and at a more accelerated rate than ever before. It’s premature to accuse the millennials, with their science-fictional name, of “killing” anything, just as it’s too soon to figure out exactly what they’ve accomplished. Marsh writes of the baby boomers: “They can’t understand that sometimes change happens for reasons other than cultural rebellion.” But it would be more accurate to say that cultural rebellion and strategies for survival come from the same place.

Return to Dimension X

Over the last week, I’ve been listening to a lot of classic radio programs from the fifties, including Dimension X, X Minus One, Stroke of Fate, and Exploring Tomorrow. They’re all science fiction shows, and although they suffered from the shifting time slots and unreliable scheduling that always seem to plague the genre, they attracted devoted followings and laid the groundwork for shows like The Twilight Zone. (Stroke of Fate was an alternate history series, and I’ll confess that I couldn’t resist starting with the episode that imagines what would have happened if Aaron Burr, rather than Alexander Hamilton, had died in that duel.) Given the growing popularity of science fiction in podcast form, it’s worth asking what writers and producers can learn from these older shows, many of which are available for streaming, and it turns out that they have a lot in common with modern efforts in the same line. Just as podcasts often benefit from sponsorships from existing media, many of these programs partnered with science fiction magazines, usually Astounding or Galaxy, both as a source of content and to take advantage of a known brand. If I were trying to start a science fiction podcast, I’d do the same thing. An established magazine would serve as a conduit for talent and ideas, and adapting, say, one story per issue could provide another way of building an audience. It couldn’t be done for free, and it can be challenging to adapt science fiction—which can be hard to follow even in print—to a radio format. But it’s because the genre is so hard to pull off that we remember the few shows that have taken the trouble to do it well. And the example of old-time radio provides a few useful guidelines here, too.

For instance, in these classic shows, we rarely hear more than two voices at once. This might seem like too obvious a point to even mention: even on the page, it’s difficult for the reader to keep track of more than two new characters at a time, and without any visual cues, it makes sense to restrict the speakers to a number that the listener can easily follow. This was also a function of budget: many of these shows were limited to casts of three actors per episode, usually two men and one woman, the latter of whom was also pressed into service for any children’s parts. But it’s worth keeping in mind as a basic structural tool, particularly when it comes to adaptations. Dimension X did a very satisfying job of presenting Ray Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles in less than half an hour, focusing on the high points of a few stories—“Rocket Summer,” “Ylla,” “And the Moon Be Still as Bright,” “There Will Come Soft Rains,” “The Off Season,” and “The Million-Year Picnic”—and reworking them as a series of two-handers. (They did much the same in an earlier episode with Bradbury’s “Mars is Heaven!”, which Stephen King later recalled in Danse Macabre as his first encounter with horror.) A scene between two characters, particularly a man and a woman, is immediately more engaging than one in which we have to work hard to follow three male voices. It buys you breathing room that you can use to advance the story, rather than wasting time playing defense. And if I were trying to adapt a story for radio and didn’t know where to begin, I’d start by asking myself if it could be structured as five two-person dialogue scenes, ideally for one actor and one actress.

Another strategy that many of these episodes share is an unapologetic reliance on narration. In the movies, voiceover is often a crutch, and it’s particularly irritating in literary adaptations that read whole chunks of the original prose over the action. But there’s a good case to be made for it in radio. It saves time, for one thing, and it can provide transitional material to bridge the gaps between narrative units. Building on the rule of thumb that I mentioned above, if there’s a piece of important action that can’t be boiled down to a two-person dialogue scene, you might just want to insert some narration and be done with it. It should be used sparingly, and only after the writer has done everything possible to convey this information in some other fashion. But it’s an important part of the radio playwright’s bag of tricks, and it would be pointless to ignore it. There’s a reason why narration plays such a central role in radio journalism and podcasting: as I’ve noted elsewhere, it deliberately usurps the role of the listener’s inner monologue, telling us what the action means so that we’re freed up to pay attention to what comes next. It’s very hard for anyone to follow along on two levels of thought at once, and most of the listener’s attention should rightly be devoted to what is happening at this moment, rather than to figuring out what has happened already. Narration is a great way of doing this, and it doesn’t need to be used throughout the episode. (An excellent example is X Minus One’s adaptation of Frederik Pohl’s “The Tunnel Under the World,” which still works like gangbusters.)

But it’s also possible to take these rules too far. Of all the radio shows I’ve heard, the most frustrating is Exploring Tomorrow, which was hosted for about half a year by none other than John W. Campbell, with stories drawn from the pages of Astounding. Campbell would speak before, during, and after each episode, commenting on the action and providing transitional or expository material, and his role as an identifiable host anticipates the persona that Rod Serling would later assume. Yet the show was a flop. Why? Campbell wasn’t a natural radio presence, which didn’t help, but his narration also detracted far more than it added: it spelled out themes that should have been implicit in the action, and it ended up undermining the drama in the process. A story like “The Cold Equations,” for instance, should have been perfect for the format—it’s already a gripping two-hander with one male and one female character, and it had been adapted successfully by previous shows. Yet the version on Exploring Tomorrow just sort of sits there, because Campbell insists on telling us what has happened and what it means. (He also spoon-feeds us a lot of exposition that should have been conveyed through dialogue, if only because it would have forced the writers to work harder.) In theory, it isn’t so far from Ira Glass’s description of radio as “anecdote then reflection, over and over,” but it doesn’t work here. Campbell was a born lecturer, both in his magazine and in the office, but people didn’t want to invite him into their homes. And if a show can’t manage that, all the craft in the world won’t save it.

Days of Futurians Past

On July 2, 1939, the First World Science Fiction Convention was held in New York. It was a landmark weekend for many reasons, but it was almost immediately overshadowed by an event that took place before it was even called to order. The preparations had been marked by a conflict between two rival convention committees, with a group called New Fandom, which the fan Sam Moskowitz had cobbled together solely for the purpose of taking over the planning process, ultimately prevailing. On the other side were the Futurians, who were less a formal club than an assortment of aspiring writers who had collected around the brilliant, infuriating Donald A. Wollheim. As the convention was about to begin, Wollheim and a handful of Futurians—including Frederik Pohl and Robert A.W. Lowndes—emerged from the elevator and headed toward the hall. What happened next has long been a matter of disagreement. According to Moskowitz, he was initially willing to let them in, but then he saw the stack of pamphlets that the group was planning to hand out, including one that called the convention committee “a dictatorship.” Thinking that they had come only to cause trouble, he asked each of them to promise to behave, and those who refused, in his words, “chose to remain without.” Wollheim later gave a very different account, claiming that the decision to exclude the Futurians, later known hyperbolically as “The Great Exclusion Act,” had been made months in advance. In any event, Wollheim and his friends left, and although there were some rumblings from the other attendees, the rest of the convention was a notable success.

So why should we care about a petty squabble that took place nearly eighty years ago, the oldest players in which were barely out of their teens? (One of the few Futurians who made it inside, incidentally, was Isaac Asimov, who wandered nervously into the convention hall, where he received an encouraging shove forward from John W. Campbell.) For me, it’s fascinating primarily because of what happened next. New Fandom won the dispute, leaving it in an undisputed position of power within the fan community. The Futurians retreated to lick their wounds. Yet the names of New Fandom’s leaders—Moskowitz, Will Sykora, and James V. Taurasi—are unlikely to ring any bells, except for those who are already steeped in the history of fandom itself. All of them remained active in fan circles, but only Moskowitz made a greater impression on the field, and that was as a critic and historian. The Futurians, by contrast, included some of the most influential figures in the entire genre. Asimov, the most famous of them all, was a Futurian, although admittedly not a particularly active one. Wollheim and Pohl made enormous contributions as writers and editors. Other names on the roster included Cyril Kornbluth, Judith Merril, James Blish, and Damon Knight, all of whom went on to have important careers. The Great Exclusion Act, in other words, was a turning point, but not the sort that anyone involved would have been able to predict at the time. The Futurians were on their way up, while the heads of New Fandom, while not exactly headed downhill, would stay stuck in the same stratum. They were at the apex of the fan pyramid, but there was yet another level to which they would never quite ascend. Next month, I’ll be taking part in a discussion at the 74th World Science Fiction Convention, which in itself is a monument to the house that New Fandom built. But the panel is called “The Futurians.”

And it’s important to understand why. As the loose offspring of several earlier organizations, New Fandom lacked the sheer closeness of the Futurians, who were joined by mutual affection, rivalry, and a shared awe of Wollheim. Many of them lived together in the Ivory Tower, which was a kind of combination dorm, writer’s colony, and flophouse. They were united by the qualities that turned them into outsiders: many had been sickly children, estranging them from their peers, and they were all wretchedly poor. (In Damon Knight’s The Futurians, Virginia Kidd, who was married to James Blish, describes how the two of them survived for months on a single bag of rice.) More than a few, notably Wollheim and John Michel, were sympathetic to communism, while others took leftist positions mostly because they liked a good fight. And of course, they were all trying—and mostly failing—to make a living by writing science fiction. As Knight shrewdly notes:

This Futurian pattern of mutual help and criticism was part of a counterculture, opposed to the dominant culture of professional science fiction writers centering around John Campbell…The Futurians would have been happy to be part of the Campbell circle, but they couldn’t sell to him; their motto, in effect, was “If you can’t join ‘em, beat ‘em.”

Like all countercultures, the Futurian lifestyle was a pragmatic solution to the problem of how to live. None of them was an overnight success. But by banding together, living on the cheap, and pitting themselves against the rest of the world, they were able to muddle along until opportunity knocked.

The difference between New Fandom and the Futurians, then, boils down to this: New Fandom was so good at being a fan organization that its members were content to be nothing but fans. The Futurians weren’t all that good at much of anything, either as fans or writers, so they regrouped and hung on until they got better. (As a result, when a genuine opening appeared, they were in a position to capitalize on it. When Pohl unexpectedly found himself the editor of Astonishing Stories at the age of nineteen, for instance, he could only fill the magazine by stocking it with stories by his Futurian friends, since nobody else was willing to write for half a cent per word.) New Fandom and its successors were machines for producing conventions, while the Futurians just quietly kept generating writers. And their success arose from the very same factors—their poverty, their physical shortcomings, their unfashionable political views, their belligerence—that had estranged them from the mainstream fan community in the first place. It didn’t last long: Wollheim, in typical fashion, blew up his own circle of friends in 1945 by suing the others for libel. But the seeds had been planted, and they would continue to grow for decades. The ones who found it hard to move on after The Great Exclusion Act were the winners. As Wollheim said to Knight:

Years later, about 1953, I got a phone call from William Sykora; he wanted to come over and talk to me…And he said what he wanted to do was get together with Michel and me, and the three of us would reorganize fandom, reorganize the clubs, and go out there and control fandom…And about ten years after that, he turned up at a Lunacon meeting, out of nowhere, with exactly the same plan. And again you had the impression that for him, it was still 1937.

My alternative canon #10: Miami Vice

Note: I’ve often discussed my favorite movies on this blog, but I also love films that are relatively overlooked or unappreciated. For the last two weeks, I’ve been looking at some of the neglected gems, problem pictures, and flawed masterpieces that have shaped my inner life, and which might have become part of the standard cinematic canon if the circumstances had been just a little bit different. You can read the previous installments here.

The most striking quality of the movies of Michael Mann—who is probably the strangest living director to be consistently entrusted with enormous budgets by major studios, at least until recently—is their ambivalent relationship with craft. It’s often noted that Mann likes to tell stories about meticulous professionals, almost exclusively men, and that their obsession with the hardware of their chosen trade mirrors the director’s own perfectionism. This is true enough. But it misses the point that for his protagonists, craft on its own is rarely sufficient: a painstaking attention to detail doesn’t save the heroes of Thief or The Insider or Collateral, who either fail spectacularly or succeed only after being forced to improvise, and their objectives in the end aren’t the ones that they had at the beginning. This feels like a more faithful picture of Mann himself, who over the last decade has seemed increasingly preoccupied with side issues and technical problems while allowing the largest elements of the narrative to fend for themselves. It’s often unclear whether the resulting confusion is the result of active indifference, uncompromising vision, or a simple inability to keep a complicated project under control. The outcome can be an unambiguous failure, like Public Enemies, or a film in which Mann’s best and worst tendencies can’t be easily separated, like Blackhat. And the most freakish example of all is Miami Vice, which is either a botched attempt to create a franchise from an eighties cop show or the most advanced movie of the century so far. But as Mayor Quimby says on The Simpsons: “It can be two things.”

I’ve watched Miami Vice with varying degrees of attention perhaps a dozen times, but I’m not sure if I could accurately describe the plot. The script and the dialogue seem to have arisen like an emergent property from the blocky, smudged images onscreen, which often threaten to push the story off the edges of the frame entirely, or to lose it in the massive depth of field. Frederik Pohl liked to describe certain writers as fiddler crabs, in whom a single aspect of their work became hypertrophied, like a grotesquely overdeveloped claw, and that indisputably applies to Mann. These days, he seems interested in nothing but texture: visual, aural, thematic. Digital video, which allows him to lovingly capture the rippling muscles on Jamie Foxx’s back or the rumpled cloth of Colin Farrell’s jacket so that you feel like you could reach out and touch it, was the medium that he had been awaiting for his entire career, and he makes such insane overuse of it here that it leaves room for almost nothing else. The film unfolds only on the night side of the city in which it supposedly takes place, just as it appears to have shot roughly half of a usable script. (This isn’t necessarily Mann’s fault: Foxx abruptly departed toward the end of production, which is why the last scene feels like a bridge to nowhere.) As with The Night of the Hunter and Blue Velvet, Miami Vice is one of those movies in which it can be hard to tell the difference between unintentional awkwardness and radical experimentation—which is inevitable when you’re forging a new grammar of film. It looked like a failed blockbuster, and it was. But you could also build an entire art form out of its shattered pieces.

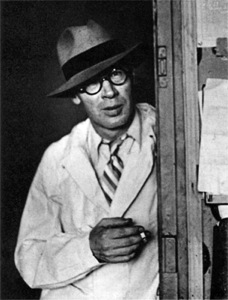

Pohl and the pulpsters

Along with the sixteen volumes of the Richard Francis Burton translation of the Arabian Nights, my other great find at this year’s Newberry Library Book Fair is the memoir The Way The Future Was by Frederik Pohl. While he never achieved the same degree of mainstream recognition as many of his contemporaries, Pohl arguably embodied more aspects of science fiction than any other figure of the golden age: he was a novelist, short story writer, essayist, literary agent to the likes of Isaac Asimov, and acclaimed editor of magazines like Galaxy and If. He made his first professional sale in 1937 and continued writing up to his death two years ago, in a career that spanned eight decades, which reminds me of Bernstein’s sad, wonderful line from Citizen Kane: “I was there before the beginning, and now it’s after the end.” Pohl’s memoir is chatty, loaded with memorable gossip, and full of valuable advice—I’ve already posted the words of wisdom that he gleaned from the editor John W. Campbell. And it’s an essential read for anyone trying to make a mark in science fiction, or indeed any kind of writing, with its chronicle of the ups and downs of a freelance author’s career. (As both writer and editor, Pohl knew how the system worked from both sides, and he’s especially eloquent on the challenges of running a magazine on a limited budget.)

The meat of the book focuses on the height of the pulp era, which saw new magazines popping up seemingly every day for fans of westerns, mysteries, adventure, true confessions, and science fiction and fantasy itself. Pohl, who became a professional editor at the age of nineteen, estimates that there were five hundred titles in all, with annual sales of about a hundred million copies—a number that seems inconceivable today, when the number of widely circulated fiction magazines, literary or otherwise, can be counted on two hands. The pulps represented one extreme of a culture that simply read more for entertainment than we do now, with the high end occupied by the likes of The Saturday Evening Post, which paid writers like F. Scott Fitzgerald thousands of dollars for a single story. (Annualized for inflation, that’s more than most mainstream publishers pay on average for an entire novel.) Readership was especially high in the sticks, where movie houses were harder to find and demand was high for a cheap, disposable diversion. They all flourished for a decade or two, and then, abruptly, they were gone, finished off first by the paper shortages of the Second World War and then by television and paperbacks. And the fact that they vanished so utterly is less surprising than the fact that a handful of titles, like Analog, have stuck around at all.

As with the heyday of paperback porn, it’s easy to romanticize the lost world of the pulps: as Theodore Sturgeon would later note, ninety percent of everything is crud, and the percentage for pulp fiction was probably higher. (Pohl says drily: “It was not all trash. But trash was the way to bet it.”) Given the pathetic rates on the low end of the scale—a penny a word at best—it’s not surprising that the good writers either got out of the pulps as soon as they could or avoided them entirely. Still, for those of us who see writing as a job like any other, it’s hard not to be enticed by the life that Pohl describes:

If you want to think of a successful pulp writer in the late thirties, imagine a man with a forty-dollar typewriter on a kitchen table. By his right hand is an ashtray with a cigarette burning in it and a cup of coffee or bottle of beer within easy reach. Stacked just past his typewriter are white sheets, carbons, and second sheets. Stacked to his left are finished pages, complete with carbon copies. he has taught himself to type reasonably neatly because he can’t afford a stenographer, and above all he has taught himself to type fast. A prolific pulpster could keep up a steady forty or fifty words a minute for long periods; there were a few writers who wrote ten thousand words a day and kept it up for years on end.

And for those who survived, the pulps were a remarkable training ground. Pohl believes that all it takes to be published are “luck, determination, and a few monkey tricks of style and plot,” and writers who made it out alive emerged with a bag of monkey tricks that no other school could offer. Pair those tricks with a good idea and a little curiosity about human life, and they were unstoppable. And although self-publishing, particularly in digital form, has revived certain aspects of that lifestyle, we’re still missing the structure that turned aspiring pulpsters into real writers, as embodied by editors like Campbell and Pohl. Editors, as Pohl notes, often took an active hand in shaping a story, either by nurturing problematic work into a publishable form or pitching ideas to authors, and even when they only served as gatekeepers, it was that sieve—or refinery—that forced their writers to grow. Pohl quotes James Blish’s observation that more than half of the major science-fiction writers of the last century were born within a year or two of 1920, which implies that it was tied to a particular event. Blish doesn’t know what this event was, and Pohl hypothesizes that it had something to do with the “social confusion and experimentation” of the thirties, but I suspect that the real answer is closer to home. The pulps were the pressure cooker that produced the popular fiction that dominated the next eighty years, and if we want to reproduce those conditions, it isn’t hard to see the limiting factor. The world already has plenty of writers; what it needs is a few hundred more paying magazines, and the editors who made them run.

John W. Campbell on the art of science fiction

I hate a story that begins with atmosphere. Get right into the story, never mind the atmosphere.

The trouble with Bob Heinlein is that he doesn’t need to write. When I want a story from him, the first thing I have to do is think up something he would like to have, like a swimming pool. The second thing is to sell him on the idea of having it. The third thing is convince him he should write a story to get the money to pay for it, instead of building it himself.

When there’s something wrong with a story, I can tell you how to fix it. When it just doesn’t come across, there’s nothing I can say.

When I think of a story idea, I give it to six different writers. It doesn’t matter if all six of them write it. They’ll all be different stories, anyway, and I’ll publish all six of them.

I want the kind of story that could be printed in a magazine of the year two thousand A.D. as a contemporary adventure story. No gee-whiz, just take the technology for granted.

—John W. Campbell, quoted by Frederik Pohl in The Way the Future Was