Posts Tagged ‘Richard Rhodes’

Back to the Future

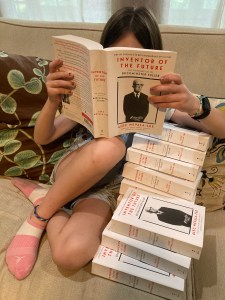

It’s hard to believe, but the paperback edition of Inventor of the Future: The Visionary Life of Buckminster Fuller is finally in stores today. As far as I’m concerned, this is the definitive version of this biography—it incorporates a number of small fixes and revisions—and it marks the culmination of a journey that started more than five years ago. It also feels like a milestone in an eventful writing year that has included a couple of pieces in the New York Times Book Review, an interview with the historian Richard Rhodes on Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer for The Atlantic online, and the usual bits and bobs elsewhere. Most of all, I’ve been busy with my upcoming biography of the Nobel Prize-winning physicist Luis W. Alvarez, which is scheduled to be published by W.W. Norton sometime in 2025. (Oppenheimer fans with sharp eyes and good memories will recall Alvarez as the youthful scientist in Lawrence’s lab, played by Alex Wolff, who shows Oppenheimer the news article announcing that the atom has been split. And believe me, he went on to do a hell of a lot more. I can’t wait to tell you about it.)

The smell of the oil

In my freshman year of college, I took a survey course on the history of science taught by Professor Everett Mendelsohn. The reading list included several selections from The Making of the Atomic Bomb by Richard Rhodes, which amounted to about a third of the entire book. As soon as I read the first chapter, however, I became so captivated that I devoured all eight hundred pages, even though I had plenty of other work to do, and it remains one of the great nonfiction reading experiences of my life. When I discovered recently that Rhodes had published a book over a decade ago titled How to Write, I became excited, and for good reason. I haven’t finished it yet, but a quick browse reveals that unlike most writing guides, which consist of nothing but platitudes, this one is packed with detailed advice for writers at work, from the use of contractions—Rhodes deliberately omitted them from his historical writing, in order to create a more formal tone—to the use of the word “had” in the past perfect tense. (“Sometimes you can quietly shift back from past perfect to past after you’ve established that you’re referring to past events, then shift again to past perfect when you’re through.” That’s good advice.) He even reveals, delightfully, that he used one of my favorite inventions, the McBee cards, to organize his notes:

In those analog days I turned to the tidy system graduate students used of ruled six-by-nine cards punched around the perimeter with rows of numbered holes. I indexed the information I typed onto the cards by a number system that related topics to holes…According to theory, you could line up the cards, slide a knitting needle through a hole, shake the stack, and shake out the cards notched for that topic. The system worked as advertised if you had only forty or fifty cards, but my stack was thick as a paving stone. It took me an hour or more to shake loose cards on a single topic. That was still better than sorting through documents by hand.

But the section that interests me the most is the one in which he discusses the practicalities of structuring a big, complicated work of history and reportage—because I’ve been wrestling with similar problems for the last two years. Like me, Rhodes was a novelist who turned to nonfiction, and he offers the best summary of the challenges involved that I’ve ever seen:

I had a nearly overwhelming quantity of information to organize. Organization took the form of parallel chronologies: the development of nuclear physics and its consequent technology, the lulls and riots of international politics, the biographies of several dozen exceptional scientists, the monstrous twentieth-century elaboration of manmade death. I couldn’t tell all these stories simultaneously. I couldn’t run them side by side, since the narrative line of a book is always a unitary line…So I decided to arrange the several stories in interrupted narrative segments, one and then the next and the next and the next and then back to the first, starting where I’d left off earlier. That’s how the phone company transmits multiple conversations on the same line. Sometimes, to reach a logical stopping point, I had to carry one segment of narrative farther forward in time than the previous segment had moved. When I cycled back to the previous segment, I usually summarized to catch up.

This organization made demands on the reader, who has to hold several narratives simultaneously in her head. In exchange, she gets scale and connection. The Making of the Atomic Bomb is in fact four or five books in one, which is why it’s so long. The alternating parallel narratives clarify historical relationships. Halting one narrative to shift to another sets up the book as a series of cliffhangers, fitting Dostoyevsky’s shrewd dramatic rule—which he learned the hard way, knocking out books chapter by chapter as newspaper serials—that a writer should end every chapter with either a door slammed shut or a door flung open.

Reading this, I felt a shiver of recognition, because these are exactly the issues that I’ve been struggling to resolve for Astounding. If anything, Rhodes had to confront these structural problems at a greater scale than I do—I’m only cutting between four major figures, while he had to work with dozens. But the underlying puzzle is much the same. When you have several narrative threads running in parallel, aside from the brief moments where they intersect, you find that you can arrange your material in an infinite number of ways. As Rhodes notes, you look for logical places to stop and start, and because the dramatic arcs of the various stories can’t be expected to line up exactly, you have to quickly make up the intervening ground whenever you switch perspectives. (I’m sometimes reminded of the challenges that Francis Ford Coppola faced in cutting between between past and present in The Godfather Part II, in which he finally realized, as I have, that the sequences should be relatively long, to minimize the points of transition.) Rhodes also talks about “clothesline” figures, which is an immensely valuable concept for journalists and other writers of nonfiction:

Characters gave me another kind of structural continuity. Leo Szilard happened to have been present at most of the significant turning points of the early atomic age. He grew up in Hungary, whence a core group of émigré scientists came who started the United States government thinking about an atomic bomb; he escaped Nazi Germany; he conceived of a nuclear chain reaction; he emigrated to the United States; he conducted one of the first experiments that revealed that fissioning uranium released enough secondary neutrons to sustain a chain reaction; he co-invented the nuclear reactor with Enrico Fermi; he helped design and build the first nuclear reactor; he gave early thought to the consequences of the atomic bomb. Szilard was a clothesline upon which I could hang the story. So was the Danish physicist Niels Bohr, who came and went less frequently but whose appearances provided moments when I could examine with him the profound changes that the discovery of nuclear fission would bring to international politics.

In my case, John W. Campbell has become my clothesline character—he was involved in one way or another at nearly every significant turning point in modern science fiction over four decades. And as I try to condense my manuscript to a manageable length, I’ve found that a good rule of thumb is to cut everything that doesn’t reflect on Campbell, sort of like the old joke about how to sculpt an elephant: “Start with a block of marble, and chip away everything that doesn’t look like an elephant.” It means losing a lot of great material, but it also whittles down what would otherwise be unworkably long biographies of Asimov, Heinlein, and Hubbard, while imposing a useful shape on what remains. And it’s nice to know that Rhodes has been there, too. (I’ve also been struck by small coincidences. Rhodes sold The Making of the Atomic Bomb with a seventy-five page proposal, which is exactly the length of the pitch I put together for Astounding. And if you really want to get into the weeds, we even got the same advance, down to the dollar, although it went a lot further back in the early eighties.) I don’t know if I’ll ever write another nonfiction book, but hacking my way through this one has given me a newfound appreciation for the work of biographers and historians. Looking back, it seems that I’ve frequently taken such books for granted, when in fact they represent a series of choices as interesting as the process behind most novels. And if you don’t feel like writing an entire book to learn how it works, Rhodes’s How to Write goes a long way toward showing you how it feels from the inside. As he observes of explaining scientific concepts to readers:

Reading through some of the classic papers in the field, I realized that I could explain a result clearly and simply by describing the physical experiment that produced it: a brass box, the air evacuated, a source of radiation in the box in the form of a vial of radon gas, and so on. Then I and the reader could visualize a process in terms of the manipulation of real laboratory objects…just as the experimenters themselves did, and could absorb the culture of scientific work at the same time—the throb of the vacuum pump, the smell of its oil.

The same is true of the act of writing. And How to Write is as good as any book I’ve ever read at capturing how the oil smells.