Posts Tagged ‘David Thomson’

Ringing in the new

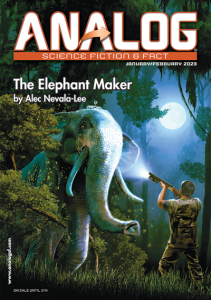

By any measure, I had a pretty productive year as a writer. My book Inventor of the Future: The Visionary Life of Buckminster Fuller was released after more than three years of work, and the reception so far has been very encouraging—it was named a New York Times Book Review Editors’ Choice, an Economist best book of the year, and, wildest of all, one of Esquire‘s fifty best biographies of all time. (My own vote would go to David Thomson’s Rosebud, his fantastically provocative biography of Orson Welles.) On the nonfiction front, I rounded out the year with pieces in Slate (on the misleading claim that Fuller somehow anticipated the principles of cryptocurrency) and the New York Times (on the remarkable British writer R.C. Sherriff and his wonderful novel The Hopkins Manuscript). Best of all, the latest issue of Analog features my 36,000-word novella “The Elephant Maker,” a revised and updated version of an unpublished novel that I started writing in my twenties. Seeing it in print, along with Inventor of the Future, feels like the end of an era for me, and I’m not sure what the next chapter will bring. But once I know, you’ll hear about it here first.

The Other Side of Welles

“The craft of getting pictures made can be so brutal and devious that there is constant need of romancing, liquor, and encouraging anecdotes,” the film critic David Thomson writes in his biography Rosebud, which is still my favorite book about Orson Welles. He’s referring, of course, to a notoriously troubled production that unfolded over the course of many years, multiple continents, and constant threats of financial collapse, held together only by the director’s vision, sheer force of will, and unfailing line of bullshit. It was called Chimes at Midnight. As Thomson says of Welles’s adaptation of the Falstaff story, which was released in 1965:

Prodigies of subterfuge and barefaced cheek were required to get the film made: the rolling plains of central Spain with mountains in the distance were somehow meant to be the wooded English countryside. Some actors were available for only a few days…so their scenes had to be done very quickly and sometimes without time to include the actors they were playing with. So [John] Gielgud did his speeches looking at a stand-in whose shoulder was all the camera saw. He had to do cutaway closeups, with timing and expression dictated by Welles. He felt at a loss, with only his magnificent technique, his trust of the language, and his fearful certainty that Welles was not to be negotiated with carrying him through.

The result, as Thomson notes, was often uneven, with “a series of spectacular shots or movie events [that] seem isolated, even edited at random.” But he closes his discussion of the movie’s troubled history with a ringing declaration that I often repeat to myself: “No matter the dreadful sound, the inappropriateness of Spanish landscapes, no matter the untidiness that wants to masquerade as poetry, still it was done.”

Those last three words have been echoing in my head ever since I saw The Other Side of the Wind, Welles’s legendary unfinished last film, which was finally edited together and released last weekend on Netflix. I’m frankly not ready yet to write anything like a review, except to say that I expect to watch it again on an annual basis for the rest of my life. And it’s essential viewing, not just for film buffs or Welles fans, but for anyone who wants to make art of any kind. Even more than Chimes at Midnight, it was willed into existence, and pairing an attentive viewing with a reading of Josh Karp’s useful book Orson Welles’s Last Movie amounts to a crash course in making movies, or just about anything else, under the the most unforgiving of circumstances. The legend goes that Citizen Kane has inspired more directorial careers than any other film, but it was also made under conditions that would never be granted to any novice director ever again. The Other Side of the Wind is a movie made by a man with nothing left except for a few good friends, occasional infusions of cash, boundless ingenuity and experience, and the soul of a con artist. (As Peter Bogdanovich reminds us in his opening narration, he didn’t even have a cell phone camera, which should make us even more ashamed about not following his example.) And you can’t watch it without permanently changing your sense of what it means to make a movie. A decade earlier, Welles had done much the same for Falstaff, as Thomson notes:

The great battle sequence, shot in one of Madrid’s parks, had its big shots with lines of horses. But then, day after day, Welles went back to the park with just a few men, some weapons, and water to make mud to obtain the terrible scenes of close slaughter that make the sequence so powerful and such a feat of montage.

That’s how The Other Side of the Wind seems to have been made—with a few men and some weapons, day after day, in the mud. And it’s going to inspire a lot of careers.

In fact, it’s temping for me to turn this post into a catalog of guerrilla filmmaking tactics, because The Other Side of the Wind is above all else an education in practical strategies for survival. Some of it is clearly visible onscreen, like the mockumentary conceit that allows scenes to be assembled out of whatever cameras or film stocks Welles happened to have available, with footage seemingly caught on the fly. (Although this might be an illusion in itself. According to Karp’s book, which is where most of this information can be found, Welles stationed a special assistant next to the cinematographer to shut off the camera as soon as he yelled “Cut,” so that not even an inch of film would be wasted.) But there’s a lot that you need to look closely to see, and the implications are intoxicating. Most of the movie was filmed on the cheapest available sets or locations—in whatever house Welles happened to be occupying at the time, on an unused studio backlot, or in a car using “poor man’s process,” with crew members gently rocking the vehicle from outside and shining moving lights through the windows. Effects were created with forced perspective, including one in which a black tabletop covered in rocks became an expanse of volcanic desert. As with Chimes of Midnight, a closeup in an interior scene might cut to another that was taken years earlier on another continent. One sequence took so long to film that Oja Kodar, Welles’s girlfriend and creative partner, visibly ages five years from one shot to another. For another scene, Welles asked Gary Graver, his cameraman, to lie on the floor with his camera so that other crew members could drag him around, a “poor man’s dolly” that he claimed to have learned from Jean Renoir. The production went on for years before casting its lead actor, and when John Huston arrived on set, Welles encouraged him to drink throughout the day, both for the sake of characterization and as a way to get the performance that he needed. As Karp writes, the shoot was “a series of strange adventures.”

This makes it even more difficult than usual to separate this movie from the myth of its making, which nobody should want to do in the first place. More than any other film that I can remember, The Other Side of the Wind is explicitly about its own unlikely creation, which was obvious to most of the participants even at the time. This extends even to the casting of Peter Bogdanovich, who plays a character so manifestly based on himself—and on his uneasy relationship to Welles—that it’s startling to learn that he was a replacement at the last minute for Rich Little, who shot hours of footage in the role before disappearing. (As Frank Marshall, who worked on the production, later recalled: “When Peter came in to play Peter, it was bizarre. I always wondered whether Peter knew.”) As good as John Huston is, if the movie is missing anything, it’s Welles’s face and voice, although he was probably wise to keep himself offscreen. But I doubt that anyone will ever mistake this movie for anything but a profoundly personal statement. As Karp writes:

Creating a narrative that kept changing along with his life, and the making of his own film, at some point Welles stopped inventing his story and began recording impressions of his world as it evolved around him. The result was a film that could never be finished. Because to finish it might have meant the end of Orson’s own artistic story—and that was impossible to accept. So he kept it going and going.

This seems about right, except that the story isn’t just about Welles, but about everyone who cared for him or what he represented. It was the testament of a man who couldn’t see tomorrow, but who imposed himself so inescapably on the present that it leaves the rest of us without any excuses. And in a strange quirk of fate, after all these decades, it seems to have appeared at the very moment that we need it the most. At the end of Rosebud, Thomson asks, remarkably, whether Welles had wasted his life on film. He answers his own question at once, in the very last line of the book, and I repeat these words to myself almost every day: “One has to do something.”

The scorpion and the snake

At the end of the most haunting speech in Citizen Kane, Mr. Bernstein says wistfully: “I’ll bet a month hasn’t gone by since that I haven’t thought of that girl.” And I don’t think a week goes by that I don’t think about Orson Welles, who increasingly seems to have led one of the richest and most revealing of all American lives. He was born in Kenosha, Wisconsin, of all places. As a young man, he allegedly put together a résumé worthy of a Hemingway protagonist, including a stint as a bullfighter, before he was out of his teens. In New York, he unquestionably made a huge impact on theater and radio, and he even had a hand in the development of the modern superhero and the invasion of science fiction into the mainstream, in the form of a classic—and possibly exaggerated—case of mass hysteria fueled by the media. His reward was what remains the most generous contract that any newcomer has ever received from a major movie studio, and he responded at the age of twenty-five with what struck many viewers, even on its first release, as the best film ever made. (If you’re an ambitious young person, this is the sort of achievement that seems vaguely plausible when you’re twenty and utterly absurd by the time you’re thirty.) After that, it was all downhill. His second picture, an equally heartbreaking story about an American family, was taken out of his hands. Welles became distracted by politics and stage conjuring, fell in love with Dolores del Río, married Rita Hayworth, and played Harry Lime in The Third Man. He spent the rest of his life wandering from one shoot to the next, acquiring a reputation as a ham and a sellout as he tried to scrounge up enough money to make a few more movies, some of them extraordinary. Over the years, he became so fat that he turned it into a joke for his audiences: “Why are there so few of you, and so many of me?” He died alone at home in the Hollywood Hills, typing up a few pages of script that he hoped to shoot the next day, shortly after taping an appearance on The Merv Griffin Show. His last film performance was as Unicron, the devourer of planets, in The Transformers: The Movie.

Even the barest outlines of his story, which I’ve written out here from memory, hint at the treasure hoard of metaphors that it offers. But that also means that we need to be cautious when we try to draw lessons from Welles, or to apply his example to the lives of others. I was once so entranced by the parallels between Welles and John W. Campbell that I devoted an entire blog post to listing them in detail, but I’ve come to realize that you could do much the same with just about any major American life of a certain profile. It presents an even greater temptation with Donald Trump, who once claimed that Citizen Kane was his favorite movie—mostly, I suspect, because it sounded better than Bloodsport. And it might be best to retire the comparisons between Kane and Trump, not to mention Jared Kushner, only because they’re too flattering. (If anything, Trump may turn out to have more in common with Hank Quinlan in Touch of Evil, the corrupt sheriff of a border town who frames a young Mexican for murder, only to meet his downfall after one of his closest associates is persuaded to wear a wire. As the madam played by Marlene Dietrich says after his death: “He was some kind of a man. What does it matter what you say about people?”) But there are times when he leaves me with no choice. As Eli Rosenberg of the Washington Post noted in a recent article, Trump is oddly fond of the lyrics to a song titled “The Snake,” which he first recited at a primary event in Cedar Falls, Iowa, saying that he had read it “the other day.” He repeatedly returned to it throughout the campaign, usually departing from his scripted remarks to do so—and it’s a measure of the dispiriting times in which we live that this attracted barely any attention, when by most standards it would qualify as one of the weirdest things that a presidential candidate had ever done. Trump read it again with a flourish at last week’s Conservative Political Action Conference: “Did anyone ever hear me do ‘The Snake’ during the campaign? I had five people outside say, ‘Could you do “The Snake?”‘ Let’s do it. I’ll do it, all right?”

In “The Snake,” a woman takes pity on a snake in the snow and carries it home, where it bites her with the explanation: “Oh shut up, silly woman. You knew damn well I was a snake before you took me in.” As Trump helpfully says: “You have to think of this in terms of immigration.” There’s a lot to unpack here, sadly, and the article in the Post points out that the original song was written by Oscar Brown Jr., a black singer and social activist from Chicago whose family isn’t particularly happy about its appropriation by Trump. Other observers, including Fox News, have pointed out its similarities to “The Scorpion and the Frog,” a fable that has made appearances in movies from The Crying Game to Drive. Most commentators trace it back to Aesop, but its first known appearance is in Welles’s Mr. Arkadin, which was released in 1955, and it’s likely that we owe its most familiar version to none other than Welles himself. (Welles had written Harry Lime’s famous speech about the cuckoo clocks just a few years earlier, and Mr. Arkadin was based on the radio series The Lives of Harry Lime.) Here’s how Welles delivers it:

And now I’m going to tell you about a scorpion. This scorpion wanted to cross a river, so he asked the frog to carry him. “No,” said the frog, “no thank you. If I let you on my back you may sting me and the sting of the scorpion is death.” “Now, where,” asked the scorpion, “is the logic in that?” For scorpions always try to be logical. “If I sting you, you will die. I will drown.” So, the frog was convinced and allowed the scorpion on his back. But just in the middle of the river, he felt a terrible pain and realized that, after all, the scorpion had stung him. “Logic!” cried the dying frog as he started under, bearing the scorpion down with him. “There is no logic in this!” “I know,” said the scorpion, “but I can’t help it—it’s my character.” Let’s drink to character.

And just as Arkadin raises the possibility that the scorpion is himself, you’ll often see arguments that that Trump subconsciously identifies with the snake. As Dan Lavoie, an aide to New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman, recently wrote on Twitter, with what seems like almost an excess of shrewdness: “Historians will view it as obvious that Trump was describing himself in ‘The Snake.’ His over-the-top recitation will be the narrative device for the first big post-Trump documentary.”

We often explain real life to ourselves in terms drawn from the movies, and one way to capture the uncanny quality of the Trump administration is to envision the rally scene in Citizen Kane with the candidate delivering “The Scorpion and the Frog” to the crowd instead—which only indicates that we’ve already crossed into a far stranger universe. But the fable also gets at a deeper affinity between Trump and Welles. In his book Rosebud, which is the best treatment of Welles that I’ve seen, the critic David Thomson returns obsessively to the figure of the scorpion, and he writes of its first appearance on film:

The Welles of this time believed in so little, and if he was to many a monstrous egotist, still he hated his own pride as much as anything. We should remember that this is the movie in which Arkadin delivers the speech—so much quoted afterward, and in better films, that it seems faintly spurious now in Arkadin—about the scorpion and the frog. It is a description of self-abuse and suicide. That Welles/Arkadin delivers it with a grandiose, shining relish only illustrates the theatricality of his most heartfelt moments. That Welles could not give the speech greater gravity or sadness surely helps us understand the man some often found odious. And so a speech full of terror became a cheap trick.

What sets Trump’s version apart, beyond even Welles’s cynicism, is that it’s both full of terror and a cheap trick. All presidents have told us fables, but only to convince us that we might be better than we truly are, as when Kane archly promises to help “the underprivileged, the underpaid, and the underfed.” Trump is the first to use such rhetoric to bring out the worst in us. He can’t help it. It’s his character. And Trump might be like Arkadin in at least one other way. Arkadin is a millionaire who claims to no longer remember the sources of his wealth, so he hires a private eye to investigate him. But he really hasn’t forgotten anything. As Thomson writes: “Rather, he wants to find out how easily anyone—the FBI, the IRS, the corps of biography—might be able to trace his guilty past…and as this blunt fool discovers the various people who could testify against him, they are murdered.”

The act of killing

Over the weekend, my wife and I watched the first two episodes of Mindhunter, the new Netflix series created by Joe Penhall and produced by David Fincher. We took in the installments over successive nights, but if you can, I’d recommend viewing them back to back—they really add up to a single pilot episode, arbitrarily divided in half, and they amount to a new movie from one of the five most interesting American directors under sixty. After the first episode, I was a little mixed, but I felt better after the next one, and although I still have some reservations, I expect that I’ll keep going. The writing tends to spell things out a little too clearly; it doesn’t always avoid clichés; and there are times when it feels like a first draft of a stronger show to come. Fincher, characteristically, sometimes seems less interested in the big picture than in small, finicky details, like the huge titles used to identify the locations onscreen, or the fussily perfect sound that the springs of the chair make whenever the bulky serial killer Ed Kemper sits down. (He also gives us two virtuoso sequences of the kind that he does better than just about anyone else—a scene in a noisy club with subtitled dialogue, which I’ve been waiting to see for years, and a long, very funny montage of two FBI agents on the road.) For long stretches, the show is about little else than the capabilities of the Red Xenomorph digital camera. Yet it also feels like a skeleton key for approaching the work of a man who, in fits and starts, has come to seem like the crucial director of our time, in large part because of his own ambivalence toward his fantasies of control.

Mindhunter is based on a book of the same name by John Douglas and Mark Olshaker about the development of behavioral science at the FBI. I read it over twenty years ago, at the peak of my morbid interest in serial killers, which is a phase that a lot of us pass through and that Fincher, revealingly, has never outgrown. Apart from Alien 3, which was project that he barely understood and couldn’t control, his real debut was Seven, in which he benefited from a mechanical but undeniably compelling script by Andrew Kevin Walker and a central figure who has obsessed him ever since. John Doe, the killer, is still the greatest example of the villain who seems to be writing the screenplay for the movie in which he appears. (As David Thomson says of Donald Sutherland’s character in JFK: “[He’s] so omniscient he must be the scriptwriter.”) Doe’s notebooks, rendered in comically lavish detail, are like a nightmare version of the notes, plans, and storyboards that every film generates, and he alternately assumes the role of writer, art director, prop master, and producer. By the end, with the hero detectives reduced to acting out their assigned parts in his play, the distinction between Doe and the director—a technical perfectionist who would later become notorious for asking his performers for hundreds of takes—seems to disappear completely. It seems to have simultaneously exhilarated and troubled Fincher, much as it did Christopher Nolan as he teased out his affinities with the Joker in The Dark Knight, and both men have spent much of their subsequent careers working through the implications of that discovery.

Fincher hasn’t always been comfortable with his association with serial killers, to the extent that he made a point of having the characters in The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo refer to “a serial murderer,” as if we’d be fooled by the change in terminology. Yet the main line of his filmography is an attempt by a surprisingly smart, thoughtful director to come to terms with his own history of violence. There were glimpses of it as early as The Game, and Zodiac, his masterpiece, is a deconstruction of the formula that turned out to be so lucrative in Seven—the killer, wearing a mask, appears onscreen for just five minutes, and some of the scariest scenes don’t have anything to do with him at all, even as his actions reverberate outward to affect the lives of everyone they touch. Dragon Tattoo, which is a movie that looks a lot better with time, identifies its murder investigation with the work of the director and his editors, who seemed to be asking us to appreciate their ingenuity in turning the elements of the book, with its five acts and endless procession of interchangeable suspects, into a coherent film. And while Gone Girl wasn’t technically a serial killer movie, it gave us his most fully realized version to date of the antagonist as the movie’s secret writer, even if she let us down with the ending that she wrote for herself. In each case, Fincher was processing his identity as a director who was drawn to big technical challenges, from The Curious Case of Benjamin Button to The Social Network, without losing track of the human thread. And he seems to have sensed how easily he could become a kind of John Doe, a master technician who toys sadistically with the lives of others.

And although Mindhunter takes a little while to reveal its strengths, it looks like it will be worth watching as Fincher’s most extended attempt to literally interrogate his assumptions. (Fincher only directed the first two episodes, but this doesn’t detract from what might have attracted him to this particular project, or the role that he played in shaping it as a producer.) The show follows two FBI agents as they interview serial killers in search of insights into their madness, with the tone set by a chilling monologue by Ed Kemper:

People who hunt other people for a vocation—all we want to talk about is what it’s like. The shit that went down. The entire fucked-upness of it. It’s not easy butchering people. It’s hard work. Physically and mentally, I don’t think people realize. You need to vent…Look at the consequences. The stakes are very high.

Take out the references to murder, and it might be the director talking. Kemper later casually refers to his “oeuvre,” leading one of the two agents to crack: “Is he Stanley Kubrick?” It’s a little out of character, but also enormously revealing. Fincher, like Nolan, has spent his career in dialogue with Kubrick, who, fairly or not, still sets the standard for obsessive, meticulous, controlling directors. Kubrick never made a movie about a serial killer, but he took the equation between the creative urge and violence—particularly in A Clockwork Orange and The Shining—as far as anyone ever has. And Mindhunter will only become the great show that it has the potential to be if it asks why these directors, and their fans, are so drawn to these stories in the first place.

Musings of a cigarette smoking man

After the great character actor Harry Dean Stanton died earlier this week, Deadspin reprinted a profile by Steve Oney from the early eighties that offers a glimpse of a man whom many of us recognized but few of us knew. It captured Stanton at a moment when he was edging into a kind of stardom, but he was still open about his doubts and struggles: “It was Eastern mysticism that began to help me. Alan Watts’s books on Zen Buddhism were a very strong influence. Taoism and Lao-tse, I read much of, along with the works of Krishnamurti. And I studied tai chi, the martial art, which is all about centering oneself.” Oney continues:

But it was the I Ching (The Book of Changes) in which Stanton found most of his strength. By his bedside he keeps a bundle of sticks wrapped in blue ribbon. Several times every week, he throws them (or a handful of coins) and then turns to the book to search out the meaning of the pattern they made. “I throw them whenever I need input,” he said. “It’s an addendum to my subconscious.” He now does this before almost everything he undertakes—interviews, films, meetings. “It has sustained and nourished me,” he said. “But I’m not qualified to expound on it.”

I was oddly moved by these lines. The I Ching doesn’t tell you what the future will be, but it offers advice on how to behave, which makes it the perfect oracle for a character actor, whose career is inextricably tied up with luck, timing, persistence, and synchronicity.

Stanton, for reasons that even he might have found hard to grasp, became its patron saint. “What he wants is that one magic part, the one they’ll mention in film dictionaries, that will finally make up for all the awful parts from early in his career,” Oney writes. That was thirty years ago, and it never really happened. Most of the entry in David Thomson’s Biographical Dictionary of Film is devoted to listing Stanton’s gigantic filmography, and its one paragraph of analysis is full of admiration for his surface, not his depths:

He is among the last of the great supporting actors, as unfailing and visually eloquent as Anthony Mann’s trees or “Mexico” in a Peckinpah film. Long ago, a French enthusiastic said that Charlton Heston was “axiomatic.” He might want that pensée back now. But Stanton is at least emblematic of sad films of action and travel. His face is like the road in the West.

This isn’t incorrect, but it’s still incomplete. In Oney’s profile, the young Sean Penn, who adopted Stanton as his mentor, offers the same sort of faint praise: “Behind that rugged old cowboy face, he’s simultaneously a man, a child, a woman—he just has this full range of emotions I really like. He’s a very impressive soul more than he is a mind, and I find that attractive.” I don’t want to discount the love there. But it’s also possible that Stanton never landed the parts that he deserved because his friends never got past that sad, wonderful face, which was a blessing that also obscured his subtle, indefinable talent.

Stanton’s great trick was to seem to sidle almost sideways into the frame, never quite taking over a film but immeasurably enriching it, and he’s been a figure on the edges of my moviegoing life for literally as long as I can remember. He appeared in what I’m pretty sure was one of the first movies I ever saw in a theater, Philip Borsos’s One Magic Christmas, which prompted Roger Ebert to write: “I am not sure exactly what I think about Harry Dean Stanton’s archangel. He is sad-faced and tender, all right, but he looks just like the kind of guy that our parents told us never to talk to.” Stanton got on my radar thanks largely to Ebert, who went so far as to define a general rule: “No movie featuring either Harry Dean Stanton or M. Emmet Walsh in a supporting role can be altogether bad.” And my memory is seasoned with stray lines and moments delivered in his voice. As the crooked, genial preacher in Uforia: “Everybody’s got to believe in something. I believe I’ll have another drink.” Or the father in Pretty in Pink, after Molly Ringwald wakes him up at home one morning: “Where am I?” Or Paul in The Last Temptation of Christ, speaking to the aged Jesus: “You know, I’m glad I met you. Because now I can forget all about you.” One movie that I haven’t seen mentioned in most retrospectives of his career is Francis Coppola’s One From the Heart, in which Stanton unobtrusively holds his own in the corner of the film that killed Zoetrope Studios. Thomson describes his work as “funny, casual, and quietly disintegrating,” and when the camera dollies to the left near the beginning of the film as he asks Frederick Forrest’s character why he keeps buying so much junk, it’s as if he’s talking to Coppola himself.

Most of all, I’ve always loved Stanton’s brief turn as Carl, the owner of the Fat Trout trailer park in Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me, in which he offered the FBI agents “a cup of Good Morning America.” And one of the great pleasures of the revival of Twin Peaks was the last look it gave us of Carl, who informed a younger friend: “I’ve been smoking for seventy-five years—every fuckin’ day.” Cigarettes were curiously central to his mystique, as surely as they shaped his face and voice. Oney writes: “In other words, Stanton is sixty going on twenty-two, a seeker who also likes to drive fast cars, dance all night, and chain-smoke cigarettes with the defiant air of a hood hanging out in the high school boy’s room.” In his last starring role, the upcoming Lucky, he’s described as having “outlived and out-smoked” his contemporaries. And, more poignantly, he said to Esquire a decade ago: “I only eat so I can smoke and stay alive.” Smoking, like casting a hexagam, feels like the quintessential pastime of the character actor—it’s the vice of those who sit and wait. In an interview that he gave a few years ago, Stanton effortlessly linked all of these themes together:

We’re not in charge of our lives and there are no answers to anything. It’s a divine mystery. Buddhism, Taoism, the Jewish Kabbalah—it’s all the same thing, but once it gets organized it’s over. You have to just accept everything. I’m still smoking a pack a day.

If you didn’t believe in the I Ching, there was always smoking, and if you couldn’t believe in either one, you could believe in Stanton. Because everybody’s got to believe in something.

The greatest trick

In the essay collection Candor and Perversion, the late critic Roger Shattuck writes: “The world scoffs at old ideas. It distrusts new ideas. It loves tricks.” He never explains what he means by “trick,” but toward the end of the book, in a chapter on Marcel Duchamp, he quotes a few lines from the poet Charles Baudelaire from the unpublished preface to Flowers of Evil:

Does one show to a now giddy, now indifferent public the working of one’s devices? Does one explain all the revision and improvised variations, right down to the way one’s sincerest impulses are mixed in with tricks and with the charlatanism indispensable to the work’s amalgamation?

Baudelaire is indulging here in an analogy from the theater—he speaks elsewhere of “the dresser’s and the decorator’s studio,” “the actor’s box,” and “the wrecks, makeup, pulleys, chains.” A trick, in this sense, is a device that the artist uses to convey an idea that also draws attention to itself, in the same way that we can simultaneously notice and accept certain conventions when we’re watching a play. In a theatrical performance, the action and its presentation are so intermingled that we can’t always say where one leaves off and the other begins, and we’re always aware, on some level, that we’re looking at actors on a stage behaving in a fashion that is necessarily stylized and artificial. In other art forms, we’re conscious of these tricks to a greater or lesser extent, and while artists are usually advised that such technical elements should be subordinated to the story, in practice, we often delight in them for their own sake.

For an illustration of the kind of trick that I mean, I can’t think of any better example than the climax of The Godfather, in which Michael Corleone attends the baptism of his godson—played by the infant Sofia Coppola—as his enemies are executed on his orders. This sequence seems as inevitable now as any scene in the history of cinema, but it came about almost by accident. The director Francis Ford Coppola had the idea to combine the christening with the killings after all of the constituent parts had already been shot, which left him with the problem of assembling footage that hadn’t been designed to fit together. As Michael Sragow recounts in The New Yorker:

[Editor Peter] Zinner, too, made a signal contribution. In a climactic sequence, Coppola had the stroke of genius (confirmed by Puzo) to intercut Michael’s serving as godfather at the christening of Connie’s baby with his minions’ savagely executing the Corleone family’s enemies. But, Zinner says, Coppola left him with thousands of feet of the baptism, shot from four or five angles as the priest delivered his litany, and relatively few shots of the assassins doing their dirty work. Zinner’s solution was to run the litany in its entirety on the soundtrack along with escalating organ music, allowing different angles of the service to dominate the first minutes, and then to build to an audiovisual crescendo with the wave of killings, the blaring organ, the priest asking Michael if he renounces Satan and all his works—and Michael’s response that he does renounce them. The effect sealed the movie’s inspired depiction of the Corleones’ simultaneous, duelling rituals—the sacraments of church and family, and the murders in the street.

Coppola has since described Zinner’s contribution as “the inspiration to add the organ music,” but as this account makes clear, the editor seems to have figured out the structure and rhythm of the entire sequence, building unforgettably on the director’s initial brainstorm.

The result speaks for itself. It’s hard to think of a more powerful instance in movies of the form of a scene, created by cuts and juxtaposition, merging with the power of its storytelling. As we watch it, consciously or otherwise, we respond both to its formal audacity and to the ideas and emotions that it expresses. It’s the ultimate trick, as Baudelaire defines it, and it also inspired one of my favorite passages of criticism, in David Thomson’s entry on Coppola in The Biographical Dictionary of Film:

When The Godfather measured its grand finale of murder against the liturgy of baptism, Coppola seemed mesmerized by the trick, and its nihilism. A Buñuel, by contrast, might have made that sequence ironic and hilarious. But Coppola is not long on those qualities, and he could not extricate himself from the engineering of scenes. The identification with Michael was complete and stricken.

Before reading these lines, I had never considered the possibility that the baptism scene could be “ironic and hilarious,” or indeed anything other than how it so overwhelmingly presents itself, although it might easily have played that way without the music. And I’ve never forgotten Thomson’s assertion that Coppola was mesmerized by his own trick, as if it had arisen from somewhere outside of himself. (It might be even more accurate to say that coming up with the notion that the sequences ought to be cut together is something altogether different from actually witnessing the result, after Zinner assembled all the pieces and added Bach’s Passacaglia and Fugue in C minor—which, notably, entwines three different themes.) Coppola was so taken by the effect that he reused it, years later, for a similar sequence in Bram Stoker’s Dracula, admitting cheerfully on the commentary track that he was stealing from himself.

It was a turning point both for Coppola and for the industry as a whole. Before The Godfather, Coppola had been a novelistic director of small, quirky stories, and afterward, like Michael coming into his true inheritance, he became the engineer of vast projects, following up on the clues that he had planted here for himself. (It’s typical of the contradictions of his career that he placed his own baby daughter at the heart of this sequence, which means that he could hardly keep from viewing the most technically nihilistic scene in all his work as something like a home movie.) And while this wasn’t the earliest movie to invite the audience to revel in its structural devices—half of Citizen Kane consists of moments like this—it may have been the first since The Birth of a Nation to do so while also becoming the most commercially successful film of all time. Along the way, it subtly changed us. In our movies, as in our politics, we’ve become used to thinking as much about how our stories are presented as about what they say in themselves. We can even come to prefer trickery, as Shattuck warns us, to true ideas. This doesn’t meant that we should renounce genuine artistic facility of the kind that we see here, as opposed to its imitation or its absence, any more than Michael can renounce Satan. But the consequences of this confusion can be profound. Coppola, the orchestrator of scenes, came to identify with the mafioso who executed his enemies with ruthless efficiency, and the beauty of Michael’s moment of damnation went a long way toward turning him into an attractive, even heroic figure, an impression that Coppola spent most of The Godfather Parts II and III trying in vain to correct. Pacino’s career was shaped by this moment as well. And we have to learn to distinguish between tricks and the truth, especially when they take pains to conceal themselves. As Baudelaire says somewhere else: “The greatest trick the devil ever pulled was convincing the world he didn’t exist.”

The space between us all

In an interview published in the July 12, 1970 issue of Rolling Stone, the rock star David Crosby said: “My time has gotta be devoted to my highest priority projects, which starts with tryin’ to save the human race and then works its way down from there.” The journalist Ben Fong-Torres prompted him gently: “But through your music, if you affect the people you come in contact with in public, that’s your way of saving the human race.” And I’ve never forgotten Crosby’s response:

But somehow operating on that premise for the last couple of years hasn’t done it, see? Somehow Sgt. Pepper’s did not stop the Vietnam War. Somehow it didn’t work. Somebody isn’t listening. I ain’t saying stop trying; I know we’re doing the right thing to live, full on. Get it on and do it good. But the inertia we’re up against, I think everybody’s kind of underestimated it. I would’ve thought Sgt. Pepper’s could’ve stopped the war just by putting too many good vibes in the air for anybody to have a war around.

He was right about one thing—the Beatles didn’t stop the war. And while it might seem as if there’s nothing new left to say about Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, which celebrates its fiftieth anniversary today, it’s worth asking what it tells us about the inability of even our greatest works of art to inspire lasting change. It’s probably ridiculous to ask this of any album. But if a test case exists, it’s here.

It seems fair to say that if any piece of music could have changed the world, it would have been Sgt. Pepper. As the academic Langdon Winner famously wrote:

The closest Western Civilization has come to unity since the Congress of Vienna in 1815 was the week the Sgt. Pepper album was released…At the time I happened to be driving across the country on Interstate 80. In each city where I stopped for gas or food—Laramie, Ogallala, Moline, South Bend—the melodies wafted in from some far-off transistor radio or portable hi-fi. It was the most amazing thing I’ve ever heard. For a brief while, the irreparably fragmented consciousness of the West was unified, at least in the minds of the young.

The crucial qualifier, of course, is “at least in the minds of the young,” which we’ll revisit later. To the critic Michael Bérubé, it was nothing less than the one week in which there was “a common culture of widely shared values and knowledge in the United States at any point between 1956 and 1976,” which seems to undervalue the moon landing, but never mind. Yet even this transient unity is more apparent than real. By the end of the sixties, the album had sold about three million copies in America alone. It’s a huge number, but even if you multiply it by ten to include those who were profoundly affected by it on the radio or on a friend’s record player, you end up with a tiny fraction of the population. To put it another way, three times as many people voted for George Wallace for president as bought a copy of Sgt. Pepper in those years.

But that’s just how it is. Even our most inescapable works of art seem to fade into insignificance when you consider the sheer number of human lives involved, in which even an apparently ubiquitous phenomenon is statistically unable to reach a majority of adults. (Fewer than one in three Americans paid to see The Force Awakens in theaters, which is as close as we’ve come in recent memory to total cultural saturation.) The art that feels axiomatic to us barely touches the lives of others, and it may leave only the faintest of marks on those who listen to it closely. The Beatles undoubtedly changed lives, but they were more likely to catalyze impulses that were already there, providing a shape and direction for what might otherwise have remained unexpressed. As Roger Ebert wrote in his retrospective review of A Hard Day’s Night:

The film was so influential in its androgynous imagery that untold thousands of young men walked into the theater with short haircuts, and their hair started growing during the movie and didn’t get cut again until the 1970s.

We shouldn’t underestimate this. But if you were eighteen when A Hard Day’s Night came out, it also means that you were born the same year as Donald Trump, who decisively won voters who were old enough to buy Sgt. Pepper on its initial release. Even if you took its message to heart, there’s a difference between the kind of change that marshals you the way that you were going and the sort that realigns society as a whole. It just isn’t what art is built to do. As David Thomson writes in Rosebud, alluding to Trump’s favorite movie: “The world is very large and the greatest films so small.”

If Sgt. Pepper failed to get us out of Vietnam, it was partially because those who were most deeply moved by it were more likely to be drafted and shipped overseas than to affect the policies of their own country. As Winner says, it united our consciousness, “at least in the young,” but all the while, the old men, as George McGovern put it, were dreaming up wars for young men to die in. But it may not have mattered. Wars are the result of forces that care nothing for what art has to say, and their operations are often indistinguishable from random chance. Sgt. Pepper may well have been “a decisive moment in the history of Western civilization,” as Kenneth Tynan hyperbolically claimed, but as Harold Bloom reminds us in The Western Canon:

Reading the very best writers—let us say Homer, Dante, Shakespeare, Tolstoy—is not going to make us better citizens. Art is perfectly useless, according to the sublime Oscar Wilde, who was right about everything.

Great works of art exist despite, not because of, the impersonal machine of history. It’s only fitting that the anniversary of Sgt. Pepper happens to coincide with a day on which our civilization’s response to climate change will be decided in a public ceremony with overtones of reality television—a more authentic reflection of our culture, as well as a more profound moment of global unity, willing or otherwise. If the opinions of rock stars or novelists counted for anything, we’d be in a very different situation right now. In “Within You Without You,” George Harrison laments “the people who gain the world and lose their soul,” which neatly elides the accurate observation that they, not the artists, are the ones who do in fact tend to gain the world. (They’re also “the people who hide themselves behind a wall.”) All that art can provide is private consolation, and joy, and the reminder that there are times when we just have to laugh, even when the news is rather sad.

Listen without prejudice

In The Biographical Dictionary of Film, David Thomson says of Tuesday Weld: “If she had been ‘Susan Weld’ she might now be known as one of our great actresses.” The same point might hold true of George Michael, who was born Georgios Kyriacos Panayiotou and chose a nom de mike—with its unfortunate combination of two first names—that made him seem frothy and lightweight. If he had called himself, say, George Parker, he might well have been regarded as one of our great songwriters, which he indisputably was. In the past, I’ve called Tom Cruise a brilliant producer who happened to be born into the body of a movie star, and George Michael had the similar misfortune of being a perversely inventive and resourceful recording artist who was also the most convincing embodiment of a pop superstar that anybody had ever seen. It’s hard to think of another performer of that era who had so complete a package: the look, the voice, the sexuality, the stage presence. The fact that he was gay and unable to acknowledge it for so long was an undeniable burden, but it also led him to transform himself into what would have been almost a caricature of erotic assertiveness if it hadn’t been delivered so earnestly. Like Cary Grant, a figure with whom he might otherwise seem to have little in common, he turned himself into exactly what he thought everyone wanted, and he did it so well that he was never allowed to be anything else.

But consider the songs. Michael was a superb songwriter from the very beginning, and “Everything She Wants,” “Last Christmas,” “Careless Whisper,” and “A Different Corner,” which he all wrote in his early twenties, should be enough to silence any doubts about his talent. His later songs could be exhausting in their insistence on doubling as statements of purpose. But it’s Faith, and particularly the first side of the album and the coda of “Kissing a Fool,” that never fails to fill me with awe. It was a clear declaration that this was a young man, not yet twenty-five, who was capable of anything, and he wasn’t shy about alerting us to the fact: the back of the compact disc reads “Written, Arranged, and Produced by George Michael.” In those five songs, Michael nimbly tackles so many different styles and tones that it threatens to make the creation of timeless pop music seem as mechanical a process as it really is. A little less sex and a lot more irony, and you’d be looking at as skilled a chameleon as Stephin Merritt—which is another comparison that I didn’t think I’d ever make. But on his best day, Michael was the better writer. “One More Try” has meant a lot to me since the moment I first heard it, while “I Want Your Sex” is one of those songs that would sound revolutionary in any decade. When you listen to the Monogamy Mix, which blends all three sections together into a monster track of thirteen minutes, you start to wonder if we’ve caught up to it even now.

These songs have been part of the background of my life for literally as long as I can remember—the music video for “Careless Whisper” was probably the first one I ever saw, except maybe for “Thriller,” and I can’t have been more than five years old. Yet I never felt like I understood George Michael in the way I thought I knew, say, the Pet Shop Boys, who also took a long time to get the recognition they deserved. (They also settled into their roles as elder statesmen a little too eagerly, while Michael never seemed comfortable with his cultural position at any age.) For an artist who told us what he thought in plenty of songs, he remained essentially unknowable. Part of it was due to that glossy voice, one of the best of its time, especially when it verged on Alison Moyet territory. But it often seemed like just another instrument, rather than a piece of himself. Unlike David Bowie, who assumed countless personas that still allowed the man underneath to peek through, Michael wore his fame, in John Updike’s words, like a mask that ate into the face. His death doesn’t feel like a personal loss to me, in the way that Bowie did, but I’ve spent just about as much time listening to his music, even if you don’t count all the times I’ve played “Last Christmas” in an endless loop on Infinite Jukebox.

In the end, it was a career that was bound to seem unfinished no matter when or how it ended. Its back half was a succession of setbacks and missed opportunities, and you could argue that its peak lasted for less than four years. The last album of his that I owned was the oddball Songs from the Last Century, in which he tried on a new role—a lounge singer of old standards—that would have been ludicrous if it hadn’t been so deeply heartfelt. It wasn’t a persuasive gesture, because he didn’t need to sing somebody else’s songs to sound like part of the canon. That was seventeen years ago, or almost half my lifetime. There were long stretches when he dropped out of my personal rotation, but he always found his way back: “Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go” even played at my wedding. “One More Try” will always be my favorite, but the snippet that has been in my head the most is the moment in “Everything She Wants” when Michael just sings: Uh huh huh / Oh, oh / Uh huh huh / Doo doo doo / La la la la… Maybe he’s just marking time, or he wanted to preserve a melodic idea that didn’t lend itself to words, or it was a reflection of the exuberance that Wesley Morris identifies in his excellent tribute in the New York Times: “There aren’t that many pop stars with as many parts of as many songs that are as exciting to sing as George Michael has—bridges, verses, the fillips he adds between the chorus during a fade-out.” But if I were trying to explain what pop music was all about to someone who had never heard it, I might just play this first.

The steady hand

Forty years ago, the cinematographer Garrett Brown invented the Steadicam. It was a stabilizer attached to a harness that allowed a camera operator, walking on foot or riding in a vehicle, to shoot the kind of smooth footage that had previously only been possible using a dolly. Before long, it had revolutionized the way in which both movies and television were shot, and not always in the most obvious ways. When we think of the Steadicam, we’re likely to remember virtuoso extended takes like the Copacabana sequence in Goodfellas, but it can also be a valuable tool even when we aren’t supposed to notice it. As the legendary Robert Elswit said recently to the New York Times:

“To me, it’s not a specialty item,” he said. “It’s usually there all the time.” The results, he added, are sometimes “not even necessarily recognizable as a Steadicam shot. You just use it to get something done in a simple way.”

Like digital video, the Steadicam has had a leveling influence on the movies. Scenes that might have been too expensive, complicated, or time-consuming to set up in the conventional manner can be done on the fly, which has opened up possibilities both for innovative stylists and for filmmakers who are struggling to get their stories made at all.

Not surprisingly, there are skeptics. In On Directing Film, which I think is the best book on storytelling I’ve ever read, David Mamet argues that it’s a mistake to think of a movie as a documentary record of what the protagonist does, and he continues:

The Steadicam (a hand-held camera), like many another technological miracle, has done injury; it has injured American movies, because it makes it so easy to follow the protagonist around, one no longer has to think, “What is the shot?” or “Where should I put the camera?” One thinks, instead, “I can shoot the whole thing in the morning.”

This conflicts with Mamet’s approach to structuring a plot, which hinges on dividing each scene into individual beats that can be expressed in purely visual terms. It’s a method that emerges naturally from the discipline of selecting shots and cutting them together, and it’s the kind of hard work that we’re often tempted to avoid. As Mamet adds in a footnote: “The Steadicam is no more capable of aiding in the creation of a good movie than the computer is in the writing of a good novel—both are labor-saving devices, which simplify and so make more attractive the mindless aspects of creative endeavor.” The casual use of the Steadicam seduces directors into conceiving of the action in terms of “little plays,” rather than in fundamental narrative units, and it removes some of the necessity of disciplined thinking beforehand.

But it isn’t until toward the end of the book that Mamet delivers his most ringing condemnation of what the Steadicam represents:

“Wouldn’t it be nice,” one might say, “if we could get this hall here, really around the corner from that door there; or to get that door here to really be the door that opens on the staircase to that door there? So we could just movie the camera from one to the next?”

It took me a great deal of effort and still takes me a great deal and will continue to take me a great deal of effort to answer the question thusly: no, not only is it not important to have those objects literally contiguous; it is important to fight against this desire, because fighting it reinforces an understanding of the essential nature of film, which is that it is made of disparate shorts, cut together. It’s a door, it’s a hall, it’s a blah-blah. Put the camera “there” and photograph, as simply as possible, that object. If we don’t understand that we both can and must cut the shots together, we are sneakily falling victim to the mistaken theory of the Steadicam.

This might all sound grumpy and abstract, but it isn’t. Take Birdman. You might well love Birdman—plenty of viewers evidently did—but I think it provides a devastating confirmation of Mamet’s point. By playing as a single, seemingly continuous shot, it robs itself of the ability to tell the story with cuts, and it inadvertently serves as an advertisement of how most good movies come together in the editing room. It’s an audacious experiment that never needs to be tried again. And it wouldn’t exist at all if it weren’t for the Steadicam.

But the Steadicam can also be a thing of beauty. I don’t want to discourage its use by filmmakers for whom it means the difference between making a movie under budget and never making it at all, as long as they don’t forget to think hard about all of the constituent parts of the story. There’s also a place for the bravura long take, especially when it depends on our awareness of the unfaked passage of time, as in the opening of Touch of Evil—a long take, made without benefit of a Steadicam, that runs the risk of looking less astonishing today because technology has made this sort of thing so much easier. And there’s even room for the occasional long take that exists only to wow us. De Palma has a fantastic one in Raising Cain, which I watched again recently, that deserves to be ranked among the greats. At its best, it can make the filmmaker’s audacity inseparable from the emotional core of the scene, as David Thomson observes of Goodfellas: “The terrific, serpentine, Steadicam tracking shot by which Henry Hill and his girl enter the Copacabana by the back exit is not just his attempt to impress her but Scorsese’s urge to stagger us and himself with bravura cinema.” The best example of all is The Shining, with its tracking shots of Danny pedaling his Big Wheel down the deserted corridors of the Overlook. It’s showy, but it also expresses the movie’s basic horror, as Danny is inexorably drawn to the revelation of his father’s true nature. (And it’s worth noting that much of its effectiveness is due to the sound design, with the alternation of the wheels against the carpet and floor, which is one of those artistic insights that never grows dated.) The Steadicam is a tool like any other, which means that it can be misused. It can be wonderful, too. But it requires a steady hand behind the camera.

The low road to Xanadu

It was a miracle of rare device,

A sunny pleasure-dome with caves of ice!—Samuel Taylor Coleridge, “Kubla Khan”

A couple of weeks ago, I wrote of Donald Trump: “He’s like Charles Foster Kane, without any of the qualities that make Kane so misleadingly attractive.” If anything, that’s overly generous to Trump himself, but it also points to a real flaw in what can legitimately be called the greatest American movie ever made. Citizen Kane is more ambiguous than it was ever intended to be, because we’re distracted throughout by our fondness for the young Orson Welles. He’s visible all too briefly in the early sequences at the Inquirer; he winks at us through his makeup as an older man; and the aura he casts was there from the beginning. As David Thomson points out in The New Biographical Dictionary of Film:

Kane is less about William Randolph Hearst—a humorless, anxious man—than a portrait and prediction of Welles himself. Given his greatest opportunity, [screenwriter Herman] Mankiewicz could only invent a story that was increasingly colored by his mixed feelings about Welles and that, he knew, would be brought to life by Welles the overpowering actor, who could not resist the chance to dress up as the old man he might one day become, and who relished the young showoff Kane just as he loved to hector and amaze the Mercury Theater.

You can see Welles in the script when Susan Alexander asks Kane if he’s “a professional magician,” or when Kane, asked if he’s still eating, replies: “I’m still hungry.” And although his presence deepens and enhances the movie’s appeal, it also undermines the story that Welles and Mankiewicz set out to tell in the first place.

As a result, the film that Hearst wanted to destroy turned out to be the best thing that could have happened to his legacy—it makes him far more interesting and likable than he ever was. The same factor tends to obscure the movie’s politics. As Pauline Kael wrote in the early seventies in the essay “Raising Kane”: “At some campus showings, they react so gullibly that when Kane makes a demagogic speech about ‘the underprivileged,’ stray students will applaud enthusiastically, and a shout of ‘Right on!’ may be heard.” But in an extraordinary review that was published when the movie was first released, Jorge Luis Borges saw through to the movie’s icy heart:

Citizen Kane…has at least two plots. The first, pointlessly banal, attempts to milk applause from dimwits: a vain millionaire collects statues, gardens, palaces, swimming pools, diamonds, cars, libraries, men and women…The second plot is far superior…At the end we realize that the fragments are not governed by any apparent unity: the detested Charles Foster Kane is a simulacrum, a chaos of appearances…In a story by Chesterton—“The Head of Caesar,” I think—the hero observes that nothing is so frightening as a labyrinth with no center. This film is precisely that labyrinth.

Borges concludes: “We all know that a party, a palace, a great undertaking, a lunch for writers and journalists, an enterprise of cordial and spontaneous camaraderie, are essentially horrendous. Citizen Kane is the first film to show such things with an awareness of this truth.” He might well be talking about the Trump campaign, which is also a labyrinth without a center. And Trump already seems to be preparing for defeat with the same defense that Kane did.

Yet if we’re looking for a real counterpart to Kane, it isn’t Trump at all, but someone standing just off to the side: his son-in-law, Jared Kushner. I’ve been interested in Kushner’s career for a long time, in part because we overlapped at college, although I doubt we’ve ever been in the same room. Ten years ago, when he bought the New York Observer, it was hard not to think of Kane, and not just because Kushner was twenty-five. It recalled the effrontery in Kane’s letter to Mr. Thatcher: “I think it would be fun to run a newspaper.” And I looked forward to seeing what Kushner would do next. His marriage to Ivanka Trump was a twist worthy of Mankiewicz, who married Kane to the president’s daughter, and as Trump lurched into politics, I wasn’t the only one wondering what Ivanka and Kushner—whose father was jailed after an investigation by Chris Christie—made of it all. Until recently, you could kid yourself that Kushner was torn between loyalty to his wife’s father and whatever else he might be feeling, even after he published his own Declaration of Principles in the Observer, writing: “My father-in-law is not an anti-Semite.” But that’s no longer possible. As the Washington Post reports, Kushner, along with former Breitbart News chief Stephen K. Bannon, personally devised the idea to seat Bill Clinton’s accusers in the family box at the second debate. The plan failed, but there’s no question that Kushner has deliberately placed himself at the center of Trump’s campaign, and that he bears an active, not passive, share of the responsibility for what promises to be the ugliest month in the history of presidential politics.

So what happened? If we’re going to press the analogy to its limit, we can picture the isolated Kane in his crumbling estate in Xanadu. It was based on Hearst Castle in San Simeon, and the movie describes it as standing on the nonexistent desert coast of Florida—but it could just as easily be a suite in Trump Tower. We all tend to surround ourselves with people with whom we agree, whether it’s online or in the communities in which we live, and if you want to picture this as a series of concentric circles, the ultimate reality distortion field must come when you’re standing in a room next to Trump himself. Now that Trump has purged his campaign of all reasonable voices, it’s easy for someone like Kushner to forget that there is a world elsewhere, and that his actions may not seem sound, or even sane, beyond those four walls. Eventually, this election will be over, and whatever the outcome, I feel more pity for Kushner than I do for his father-in-law. Trump can only stick around for so much longer, while Kushner still has half of his life ahead of him, and I have a feeling that it’s going to be defined by his decisions over the last three months. Maybe he’ll realize that he went straight from the young Kane to the old without any of the fun in between, and that his only choice may be to wall himself up in Xanadu in his thirties, with the likes of Christie, Giuliani, and Gingrich for company. As the News on the March narrator says in Kane: “An emperor of newsprint continued to direct his failing empire, vainly attempted to sway, as he once did, the destinies of a nation that had ceased to listen to him, ceased to trust him.” It’s a tragic ending for an old man. But it’s even sadder for a young one.

The excerpt opinion

“It’s the rare writer who cannot have sentences lifted from his work,” Norman Mailer once wrote. What he meant is that if a reviewer is eager to find something to mock, dismiss, or pick apart, any interesting book will provide plenty of ammunition. On a simple level of craft, it’s hard for most authors to sustain a high pitch of technical proficiency in every line, and if you want to make a novelist seem boring or ordinary, you can just focus on the sentences that fall between the high points. In his famously savage takedown of Thomas Harris’s Hannibal, Martin Amis quotes another reviewer who raved: “There is not a single ugly or dead sentence.” Amis then acidly observes:

Hannibal is a genre novel, and all genre novels contain dead sentences—unless you feel the throb of life in such periods as “Tommaso put the lid back on the cooler” or “Eric Pickford answered” or “Pazzi worked like a man possessed” or “Margot laughed in spite of herself” or “Bob Sneed broke the silence.”

Amis knows that this is a cheap shot, and he glories in it. But it isn’t so different from what critics do when they list the awful sentences from a current bestseller or nominate lines for the Bad Sex in Fiction Award. I laugh at this along with anyone else, but I also wince a little, because there are few authors alive who aren’t vulnerable to that sort of treatment. As G.K. Chesterton pointed out: “You could compile the worst book in the world entirely out of selected passages from the best writers in the world.”

This is even more true of authors who take considerable stylistic or thematic risks, which usually result in individual sentences that seem crazy or, worse, silly. The fear of seeming ridiculous is what prevents a lot of writers from taking chances, and it isn’t always unjustified. An ambitious novel opens itself up to savaging from all sides, precisely because it provides so much material that can be turned against the author when taken out of context. And it doesn’t need to be malicious, either: even objective or actively sympathetic critics can be seduced by the ease with which a writer can be excerpted to make a case. I’ve become increasingly daunted by the prospect of distilling the work of Robert A. Heinlein, for example, because his career was so long, varied, and often intentionally provocative that you can find sentences to support any argument about him that you want to make. (It doesn’t help that his politics evolved drastically over time, and they probably would have undergone several more transformations if he had lived for longer.) This isn’t to say that his opinions aren’t a fair target for criticism, but any reasonable understanding of who Heinlein was and what he believed—which I’m still trying to sort out for myself—can’t be conveyed by a handful of cherry-picked quotations. Literary biography is useful primarily to the extent that it can lay out a writer’s life in an orderly fashion, providing a frame that tells us something about the work that we wouldn’t know by encountering it out of order. But even that involves a process of selection, as does everything else about a biography. The biographer’s project isn’t essentially different from that of a working critic or reviewer: it just takes place on a larger scale.

And it’s worth noting that prolific critics themselves are particularly susceptible to this kind of treatment. When Renata Adler described Pauline Kael’s output as “not simply, jarringly, piece by piece, line by line, and without interruption, worthless,” any devotee of Kael’s work had to disagree—but it was also impossible to deny that there was plenty of evidence for the prosecution. If you’re determined to hate Roger Ebert, you just have to search for the reviews in which his opinions, written on deadline, weren’t sufficiently in line with the conclusions reached by posterity, as when he unforgivably gave only three stars to The Godfather Part II. And there isn’t a single page in the work of David Thomson, who is probably the most interesting movie critic who ever lived, that couldn’t be mined for outrageous, idiotic, or infuriating statements. I still remember a review on The A.V. Club of How to Watch a Movie that quoted lines like this:

Tell me a story, we beg as children, while wanting so many other things. Story will put off sleep (or extinction) and the child’s organism hardly trusts the habit of waking yet.

And this:

You came into this book under deceptive promises (mine) and false hopes (yours). You believed we might make decisive progress in the matter of how to watch a movie. So be it, but this was a ruse to make you look at life.

The reviewer quoted these sentences as examples of the book’s deficiencies, and they were duly excoriated in the comments. But anyone who has really read Thomson knows that such statements are part of the package, and removing them would also deny most of what makes him so fun, perverse, and valuable.

So what’s a responsible reviewer to do? We could start, maybe, by quoting longer or complete sections, rather than sentences in isolation, and by providing more context when we offer up just a line or two. We can also respect an author’s feelings, explicit or otherwise, about what sections are actually important. In the passage I mentioned at the beginning of this post, which is about John Updike, Mailer goes on to quote a few sentences from Rabbit, Run, and he adds:

The first quotation is taken from the first five sentences of the book, the second is on the next-to-last page, and the third is nothing less than the last three sentences of the novel. The beginning and end of a novel are usually worked over. They are the index to taste in the writer.

That’s a pretty good rule, and it ensures that the critic is discussing something reasonably close to what the writer intended to say. Best of all, we can approach the problem of excerpting with a kind of joy in the hunt: the search for the slice of a work that will stand as a synecdoche of the whole. In the book U & I, which is also about Updike, Nicholson Baker writes about the “standardized ID phrase” and “the aphoristic consensus” and “the jingle we will have to fight past at some point in the future” to see a writer clearly again, just as fans of Joyce have to do their best to forget about “the ineluctable modality of the visible” and “yes I said yes I will Yes.” For a living author, that repository of familiar quotations is constantly in flux, and reviewers might approach their work with a greater sense of responsibility if they realized that they were playing a part in creating it—one tiny excerpt at a time.

The double awareness

Mechanical excellence is the only vehicle of genius.

—William Blake

Earlier this week, I picked up a copy of Strasberg at the Actor’s Studio, a collection of transcribed lessons from the legendary acting teacher Lee Strasberg, who is best known to viewers today for his role as Hyman Roth in The Godfather Part II. (I was watching it again recently, and I was newly amazed at how great Strasberg is—you can’t take your eyes off him whenever he’s onscreen.) The book is loaded with insights from one of method acting’s foremost theorists and practitioners, but the part that caught my eye was what Strasberg says about Laurence Olivier:

When we see certain performances of Olivier we sometimes tend to say, “Well, it’s a little superficial.” Why are they superficial? There is great imagination in them, more imagination than in a lot of performances which are more organic because Olivier is giving of himself more completely at each moment. Is it that his idea of the part and the play is not clear? On the contrary, it is marvelously clear. You know exactly why he is doing each little detail. In his performance you watch an actor’s mind, fantastic in its scope and greatness, working and understanding the needs of the scene. He understands the character better than I ever will. I don’t even want to understand the character as much as he does, because I think it is his understanding that almost stops him from the completeness of the response.

Strasberg goes on to conclude: “If we criticize Larry Olivier’s performance, it is only because it seems to us the outline of a performance. It is not a performance. Olivier has a fine talent, but you get from him all of the actor’s thought and a lot of his skill and none of the actual talent that he has.” And while I don’t intend to wade into a comparison of the method and classical approaches to acting, which I don’t have the technical background to properly discuss, Strasberg’s comments strike me as intuitively correct. We’ve all had the experience of watching an artist and becoming more preoccupied by his or her thought process than in the organic meaning of the work itself. I’ve said that David Mamet’s movies play like fantastic first drafts in which we’re a little too aware of the logic behind each decision, and it’s almost impossible for me to watch Kevin Spacey, for instance, without being aware of the cleverness of his choices, rather than losing myself in the story he’s telling. Sometimes that sheer meretriciousness can be delightful in itself, and it’s just about the only thing that kept me watching the third season of House of Cards. As David Thomson said: “[Spacey] can be our best actor, but only if we accept that acting is a bag of tricks that leaves scant room for being a real and considerate human being.”

But there’s a deeper truth here, which is that under ideal conditions, our consciousness of an artist’s choices can lead to a kind of double awareness: it activates our experience of both the technique and the story, and it culminates in something more compelling than either could be on its own. And Olivier himself might agree. He once said of his own approach to acting:

I’ve frequently observed things, and thank God, if I haven’t got a very good memory for anything else, I’ve got a memory for little details. I’ve had things in the back of my mind for as long as eighteen years before I’ve used them. And it works sometimes that, out of one little thing that you’ve seen somebody do, something causes you to store it up. In the years that follow you wonder what it was that made them do it, and, ultimately, you find in that the illuminating key to a whole bit of characterization…And so, with one or two extraneous externals, I [begin] to build up a character, a characterization. I’m afraid I do work mostly from the outside in. I usually collect a lot of details, a lot of characteristics, and find a creature swimming about somewhere in the middle of them.

When we watch the resulting performance, we’re both caught up in the moment and aware of the massive reserves of intelligence and craft that the actor has brought to bear on it over an extended period of time—which, paradoxically, can heighten the emotional truth of the scene, as we view it with some of the same intensity of thought that Olivier himself did.

And one of the most profound things that any actor can do is to move us while simultaneously making us aware of the tools he’s using. There’s no greater example than Marlon Brando, who, at his best, was both the ultimate master of the method technique and a genius at this kind of trickery who transcended even Olivier. When he puts on Eva Marie Saint’s glove in On the Waterfront or cradles the cat in his arms in The Godfather, we’re both struck by the irrational rightness of the image and conscious of the train of thought behind it. (Olivier himself was once up for the role of Don Corleone, which feels like a hinge moment in the history of movies, even if I suspect that both he and Brando would have fallen back on many of the same tactics.) And Brando’s work in Last Tango in Paris is both agonizingly intimate and exposed—it ruined him for serious work for the rest of his career—and an anthology of good tricks derived from a lifetime of acting. I think it’s the greatest male performance in the history of movies, and it works precisely because of the double awareness that it creates, in which we’re watching both Brando himself and the character of Paul, who is a kind of failed Brando. This superimposition of actor over character couldn’t exist if some of those choices weren’t obvious or transparent, and it changes the way it lives in our imagination. As Pauline Kael said in the most famous movie review ever written: “We are watching Brando throughout this movie, with all the feedback that that implies…If Brando knows this hell, why should we pretend we don’t?”

How I like my Scully

Note: Spoilers follow for “Mulder and Scully Meet the Were-Monster.”

Dana Scully, as I’ve written elsewhere, is my favorite television character of all time, but really, it would be more accurate to say that I’m in love with a version of Scully who appeared in maybe a dozen or so episodes of The X-Files. Scully always occupied a peculiar position on the series: she was rarely the driving force behind any given storyline, and she was frequently there as a sounding board or a sparring partner defined by her reactions to Mulder. As such, she often ended up facilitating stories that had little to do with her strengths, as if her personality was formed by the negative space in which Mulder’s obsessions collided the plot points of a particular episode. She was there to move things along, and she could be a badass or a convenient victim, a quip machine or a martyr, based solely on what the episode needed to get to its destination. That’s true of many protagonists on network dramas or procedurals: they’re under so much pressure to advance the plot that they don’t have time to do anything else. But even in the early seasons, a quirkier, far more interesting character was emerging at the edges of the frame. I’m not talking about the Scully of the abduction or cancer or pregnancy arcs, who was defined by her pain—and, more insidiously, by her body. I’m talking about the Dana Scully of whom I once wrote: “The more I revisit the show, the more Scully’s skepticism starts to seem less like a form of denial than a distinct, joyous, sometimes equally insane approach to the game.”