Posts Tagged ‘Christopher Nolan’

Back to the Future

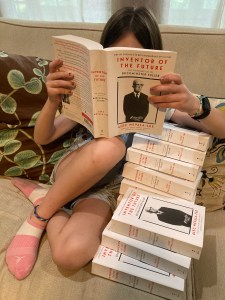

It’s hard to believe, but the paperback edition of Inventor of the Future: The Visionary Life of Buckminster Fuller is finally in stores today. As far as I’m concerned, this is the definitive version of this biography—it incorporates a number of small fixes and revisions—and it marks the culmination of a journey that started more than five years ago. It also feels like a milestone in an eventful writing year that has included a couple of pieces in the New York Times Book Review, an interview with the historian Richard Rhodes on Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer for The Atlantic online, and the usual bits and bobs elsewhere. Most of all, I’ve been busy with my upcoming biography of the Nobel Prize-winning physicist Luis W. Alvarez, which is scheduled to be published by W.W. Norton sometime in 2025. (Oppenheimer fans with sharp eyes and good memories will recall Alvarez as the youthful scientist in Lawrence’s lab, played by Alex Wolff, who shows Oppenheimer the news article announcing that the atom has been split. And believe me, he went on to do a hell of a lot more. I can’t wait to tell you about it.)

The Ballad of Jack and Rose

Note: To commemorate the twentieth anniversary of the release of Titanic, I’m republishing a post that originally appeared, in a slightly different form, on April 16, 2012.

Is it possible to watch Titanic again with fresh eyes? Was it ever possible? When I caught Titanic 3D five years ago in Schaumburg, Illinois, it had been a decade and a half since I last saw it. (I’ve since watched it several more times, mostly while writing an homage in my novel Eternal Empire.) On its initial release, I liked it a lot, although I wouldn’t have called it the best movie of a year that gave us L.A. Confidential, and since then, I’d revisited bits and pieces of it on television, but had never gone back and watched the whole thing. All the same, my memories of it remained positive, if somewhat muted, so I was curious to see what my reaction would be, and what I found is that this is a really good, sometimes even great movie that looks even better with time. Once we set aside our preconceived notions, we’re left with a spectacularly well-made film that takes a lot of risks and seems motivated by a genuine, if vaguely adolescent, fascination with the past, an unlikely labor of love from a prodigiously talented director who willed himself into a genre that no one would have expected him to understand—the romantic epic—and emerged with both his own best work and a model of large-scale popular storytelling.

So why is this so hard for some of us to admit? The trouble, I think, is that the factors that worked so strongly in the film’s favor—its cinematography, special effects, and art direction; its beautifully choreographed action; its incredible scale—are radically diminished on television, which was the only way that it could be seen for a long time. On the small screen, we lose all sense of scope, leaving us mostly with the charisma of its two leads and conventional dramatic elements that James Cameron has never quite been able to master. Seeing Titanic in theaters again reminds us of why we responded to it in the first place. It’s also easier to appreciate that it was made at precisely the right moment in movie history, an accident of timing that allowed it to take full advantage of digital technology while still deriving much of its power from stunts, gigantic sets, and practical effects. If it were made again today, even by Cameron himself, it’s likely that much of this spectacle would be rendered on computers, which would be a major aesthetic loss. A huge amount of this film’s appeal lies in its physicality, in those real crowds and flooded stages, all of which can only be appreciated in the largest venue possible. Titanic is still big; it’s the screens that got small.

It’s also time to retire the notion that James Cameron is a bad screenwriter. It’s true that he doesn’t have any ear for human conversation, and that he tends to freeze up when it comes to showing two people simply talking—I’m morbidly curious to see what he’d do with a conventional drama, but I’m not sure that I want to see the result. Yet when it comes to structuring exciting stories on the largest possible scale, and setting up and delivering climactic set pieces and payoffs, he’s without equal. I’m a big fan of Christopher Nolan, for instance—I think he’s the most interesting mainstream filmmaker alive—but his films can seem fussy and needlessly intricate compared to the clean, powerful narrative lines that Cameron sets up here. (The decision, for instance, to show us a simulation of the Titanic’s sinking before the disaster itself is a masterstroke: it keeps us oriented throughout an hour of complex action that otherwise would be hard to understand.) Once the movie gets going, it never lets up. It moves toward its foregone conclusion with an efficiency, confidence, and clarity that Peter Jackson, or even Spielberg, would have reason to envy. And its production was one of the last great adventures—apart from The Lord of the Rings—that Hollywood ever allowed itself.

Despite James Cameron’s reputation as a terror on the set, I met him once, and he was very nice to me. In 1998, as an overachieving high school senior, I was a delegate at the American Academy of Achievement’s annual Banquet of the Golden Plate in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, an extraordinarily surreal event that I hope to discuss in more detail one of these days. The high point of the weekend was the banquet itself, a black-tie affair in a lavish indoor auditorium with the night’s honorees—a range of luminaries from science, politics, and the arts—seated in alphabetical order at the periphery of the room. One of them was James Cameron, who had swept the Oscars just a few months earlier. Halfway through the evening, leaving my own seat, I went up to his table to say hello, only to find him surrounded by a flock of teenage girls anxious to know what it was like to work with Leonardo DiCaprio. Seeing that there was no way of approaching him yet, I chatted for a bit with a man seated nearby, who hadn’t attracted much, if any, attention. We made small talk for a minute or two, but when I saw an opening with Cameron, I quickly said goodbye, leaving the other guest on his own. It was Dick Cheney.

The act of killing

Over the weekend, my wife and I watched the first two episodes of Mindhunter, the new Netflix series created by Joe Penhall and produced by David Fincher. We took in the installments over successive nights, but if you can, I’d recommend viewing them back to back—they really add up to a single pilot episode, arbitrarily divided in half, and they amount to a new movie from one of the five most interesting American directors under sixty. After the first episode, I was a little mixed, but I felt better after the next one, and although I still have some reservations, I expect that I’ll keep going. The writing tends to spell things out a little too clearly; it doesn’t always avoid clichés; and there are times when it feels like a first draft of a stronger show to come. Fincher, characteristically, sometimes seems less interested in the big picture than in small, finicky details, like the huge titles used to identify the locations onscreen, or the fussily perfect sound that the springs of the chair make whenever the bulky serial killer Ed Kemper sits down. (He also gives us two virtuoso sequences of the kind that he does better than just about anyone else—a scene in a noisy club with subtitled dialogue, which I’ve been waiting to see for years, and a long, very funny montage of two FBI agents on the road.) For long stretches, the show is about little else than the capabilities of the Red Xenomorph digital camera. Yet it also feels like a skeleton key for approaching the work of a man who, in fits and starts, has come to seem like the crucial director of our time, in large part because of his own ambivalence toward his fantasies of control.

Mindhunter is based on a book of the same name by John Douglas and Mark Olshaker about the development of behavioral science at the FBI. I read it over twenty years ago, at the peak of my morbid interest in serial killers, which is a phase that a lot of us pass through and that Fincher, revealingly, has never outgrown. Apart from Alien 3, which was project that he barely understood and couldn’t control, his real debut was Seven, in which he benefited from a mechanical but undeniably compelling script by Andrew Kevin Walker and a central figure who has obsessed him ever since. John Doe, the killer, is still the greatest example of the villain who seems to be writing the screenplay for the movie in which he appears. (As David Thomson says of Donald Sutherland’s character in JFK: “[He’s] so omniscient he must be the scriptwriter.”) Doe’s notebooks, rendered in comically lavish detail, are like a nightmare version of the notes, plans, and storyboards that every film generates, and he alternately assumes the role of writer, art director, prop master, and producer. By the end, with the hero detectives reduced to acting out their assigned parts in his play, the distinction between Doe and the director—a technical perfectionist who would later become notorious for asking his performers for hundreds of takes—seems to disappear completely. It seems to have simultaneously exhilarated and troubled Fincher, much as it did Christopher Nolan as he teased out his affinities with the Joker in The Dark Knight, and both men have spent much of their subsequent careers working through the implications of that discovery.

Fincher hasn’t always been comfortable with his association with serial killers, to the extent that he made a point of having the characters in The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo refer to “a serial murderer,” as if we’d be fooled by the change in terminology. Yet the main line of his filmography is an attempt by a surprisingly smart, thoughtful director to come to terms with his own history of violence. There were glimpses of it as early as The Game, and Zodiac, his masterpiece, is a deconstruction of the formula that turned out to be so lucrative in Seven—the killer, wearing a mask, appears onscreen for just five minutes, and some of the scariest scenes don’t have anything to do with him at all, even as his actions reverberate outward to affect the lives of everyone they touch. Dragon Tattoo, which is a movie that looks a lot better with time, identifies its murder investigation with the work of the director and his editors, who seemed to be asking us to appreciate their ingenuity in turning the elements of the book, with its five acts and endless procession of interchangeable suspects, into a coherent film. And while Gone Girl wasn’t technically a serial killer movie, it gave us his most fully realized version to date of the antagonist as the movie’s secret writer, even if she let us down with the ending that she wrote for herself. In each case, Fincher was processing his identity as a director who was drawn to big technical challenges, from The Curious Case of Benjamin Button to The Social Network, without losing track of the human thread. And he seems to have sensed how easily he could become a kind of John Doe, a master technician who toys sadistically with the lives of others.

And although Mindhunter takes a little while to reveal its strengths, it looks like it will be worth watching as Fincher’s most extended attempt to literally interrogate his assumptions. (Fincher only directed the first two episodes, but this doesn’t detract from what might have attracted him to this particular project, or the role that he played in shaping it as a producer.) The show follows two FBI agents as they interview serial killers in search of insights into their madness, with the tone set by a chilling monologue by Ed Kemper:

People who hunt other people for a vocation—all we want to talk about is what it’s like. The shit that went down. The entire fucked-upness of it. It’s not easy butchering people. It’s hard work. Physically and mentally, I don’t think people realize. You need to vent…Look at the consequences. The stakes are very high.

Take out the references to murder, and it might be the director talking. Kemper later casually refers to his “oeuvre,” leading one of the two agents to crack: “Is he Stanley Kubrick?” It’s a little out of character, but also enormously revealing. Fincher, like Nolan, has spent his career in dialogue with Kubrick, who, fairly or not, still sets the standard for obsessive, meticulous, controlling directors. Kubrick never made a movie about a serial killer, but he took the equation between the creative urge and violence—particularly in A Clockwork Orange and The Shining—as far as anyone ever has. And Mindhunter will only become the great show that it has the potential to be if it asks why these directors, and their fans, are so drawn to these stories in the first place.

The man with the plan

This month marks the twenty-fifth anniversary of the release of Reservoir Dogs, a film that I loved as much as just about every other budding cinephile who came of age in the nineties. Tom Shone has a nice writeup on its legacy in The New Yorker, and while I don’t agree with every point that he makes—he dismisses Kill Bill, which is a movie that means so much to me that I named my own daughter after Beatrix Kiddo—he has insights that can’t be ignored: “Quentin [Tarantino] became his worst reviews, rather in the manner of a boy who, falsely accused of something, decides that he might as well do the thing for which he has already been punished.” And there’s one paragraph that strikes me as wonderfully perceptive:

So many great filmmakers have made their debuts with heist films—from Woody Allen’s Take the Money and Run to Michael Mann’s Thief to Wes Anderson’s Bottle Rocket to Bryan Singer’s The Usual Suspects—that it’s tempting to see the genre almost as an allegory for the filmmaking process. The model it offers first-time filmmakers is thus as much economic as aesthetic—a reaffirmation of the tenant that Jean-Luc Godard attributed to D. W. Griffith: “All you need to make a movie is a girl and a gun.” A man assembles a gang for the implementation of a plan that is months in the rehearsal and whose execution rests on a cunning facsimile of midmorning reality going undetected. But the plan meets bumpy reality, requiring feats of improvisation and quick thinking if the gang is to make off with its loot—and the filmmaker is to avoid going to movie jail.

And while you could nitpick the details of this argument—Singer’s debut was actually Public Access, a movie that nobody, including me, has seen—it gets at something fundamental about the art of film, which lies at the intersection of an industrial process and a crime. I’ve spoken elsewhere about how Inception, my favorite movie of the last decade, maps the members of its mind heist neatly onto the crew of a motion picture: Cobb is the director, Saito the producer, Ariadne the set designer, Eames the actor, and Arthur is, I don’t know, the line producer, while Fischer, the mark, is a surrogate for the audience itself. (For what it’s worth, Christopher Nolan has stated that any such allegory was unconscious, although he seems to have embraced it after the fact.) Most of the directors whom Shone names are what we’d call auteur figures, and aside from Singer, all of them wear a writer’s hat, which can obscure the extent to which they depend on collaboration. Yet in their best work, it’s hard to imagine Singer without Christopher McQuarrie, Tarantino without editor Sally Menke, or Wes Anderson without Owen Wilson, not to mention the art directors, cinematographers, and other skilled craftsmen required to finish even the most idiosyncratic and personal movie. Just as every novel is secretly about the process of its own creation, every movie is inevitably about making movies, which is the life that its creators know most intimately. One of the most exhilarating things that a movie can do is give us a sense of the huddle between artists, which is central to the appeal of The Red Shoes, but also Mission: Impossible—Rogue Nation, in which Tom Cruise told McQuarrie that he wanted to make a film about what it was like for the two of them to make a film.

But there’s also an element of criminality, which might be even more crucial. I’m not the first person to point out that there’s something illicit in the act of watching images of other people’s lives projected onto a screen in a darkened theater—David Thomson, our greatest film critic, has built his career on variations on that one central insight. And it shouldn’t surprise us if the filmmaking process itself takes on aspects of something done in the shadows, in defiance of permits, labor regulations, and the orderly progression of traffic. (Werner Herzog famously advised aspiring directors to carry bolt cutters everywhere: “If you want to do a film, steal a camera, steal raw stock, sneak into a lab and do it!”) If your goal is to tell a story about putting together a team for a complicated project, it could be about the Ballet Lermontov or the defense of a Japanese village, and the result might be even greater. But it would lack the air of illegality on which the medium thrives, both in its dreamlife and in its practical reality. From the beginning, Tarantino seems to have sensed this. He’s become so famous for reviving the careers of neglected figures for the sake of the auras that they provide—John Travolta, Pam Grier, Robert Forster, Keith Carradine—that it’s practically become his trademark, and we often forget that he did it for the first time in Reservoir Dogs. Lawrence Tierney, the star of Dillinger and Born to Kill, had been such a menacing presence both onscreen and off that that he was effectively banned from Hollywood after the forties, and he remained a terrifying presence even in old age. He terrorized the cast of Seinfield during his guest appearance as Elaine’s father, and one of my favorite commentary tracks from The Simpsons consists of the staff reminiscing nervously about how much he scared them during the recording of “Marge Be Not Proud.”

Yet Tarantino still cast him as Joe Cabot, the man who sets up the heist, and Tierney rewarded him with a brilliant performance. Behind the scenes, it went more or less as you might expect, as Tarantino recalled much later:

Tierney was a complete lunatic by that time—he just needed to be sedated. We had decided to shoot his scenes first, so my first week of directing was talking with this fucking lunatic. He was personally challenging to every aspect of filmmaking. By the end of the week everybody on set hated Tierney—it wasn’t just me. And in the last twenty minutes of the first week we had a blowout and got into a fist fight. I fired him, and the whole crew burst into applause.

But the most revealing thing about the whole incident is that an untested director like Tarantino felt capable of taking on Tierney at all. You could argue that he already had an inkling of what he might become, but I’d prefer to think that he both needed and wanted someone like this to symbolize the last piece of the picture. Joe Cabot is the man with the plan, and he’s also the man with the money. (In the original script, Joe says into the phone: “Sid, stop, you’re embarrassing me. I don’t need to be told what I already know. When you have bad months, you do what every businessman in the world does, I don’t care if he’s Donald Trump or Irving the tailor. Ya ride it out.”) It’s tempting to associate him with the producer, but he’s more like a studio head, a position that has often drawn men whose bullying and manipulation is tolerated as long as they can make movies. When he wrote the screenplay, Tarantino had probably never met such a creature in person, but he must have had some sense of what was in store, and Reservoir Dogs was picked up for distribution by a man who fit the profile perfectly—and who never left Tarantino’s side ever again. His name was Harvey Weinstein.

Thinking on your feet

The director Elia Kazan, whose credits included A Streetcar Named Desire and On the Waterfront, was proud of his legs. In his memoirs, which the editor Robert Gottlieb calls “the most gripping and revealing book I know about the theater and Hollywood,” Kazan writes of his childhood:

Everything I wanted most I would have to obtain secretly. I learned to conceal my feelings and to work to fulfill them surreptitiously…What I wanted most I’d have to take—quietly and quickly—from others. Not a logical step, but I made it at a leap. I learned to mask my desires, hide my truest feeling; I trained myself to live in deprivation, in silence, never complaining, never begging, in isolation, without expecting kindness or favors or even good luck…I worked waxing floors—forty cents an hour. I worked at a small truck farm across the road—fifty cents an hour. I caddied every afternoon I could at the Wykagyl Country Club, carrying the bags of middle-aged women in long woolen skirts—a dollar a round. I spent nothing. I didn’t take trolleys; I walked. Everywhere. I have strong leg muscles from that time.

The italics are mine, but Kazan emphasized his legs often enough on his own. In an address that he delivered at a retrospective at Wesleyan University in 1973, long after his career had peaked, he told the audience: “Ask me how with all that knowledge and all that wisdom, and all that training and all those capabilities, including the strong legs of a major league outfielder, how did I manage to mess up some of the films I’ve directed so badly?”

As he grew older, Kazan’s feelings about his legs became inseparable from his thoughts on his own physical decline. In an essay titled “The Pleasures of Directing,” which, like the address quoted above, can be found in the excellent book Kazan on Directing, Kazan observes sadly: “They’ve all said it. ‘Directing is a young man’s game.’ And time passing proves them right.” He continues:

What goes first? With an athlete, the legs go first. A director stands all day, even when he’s provided with chairs, jeeps, and limos. He walks over to an actor, stands alongside and talks to him; with a star he may kneel at the side of the chair where his treasure sits. The legs do get weary. Mine have. I didn’t think it would happen because I’ve taken care of my body, always exercised. But I suddenly found I don’t want to play singles. Doubles, okay. I stand at the net when my partner serves, and I don’t have to cover as much ground. But even at that…

I notice also that I want a shorter game—that is to say also, shorter workdays, which is the point. In conventional directing, the time of day when the director has to be most able, most prepared to push the actors hard and get what he needs, usually the close-ups of the so-called “master scene,” is in the afternoon. A director can’t afford to be tired in the late afternoon. That is also the time—after the thoughtful quiet of lunch—when he must correct what has not gone well in the morning. He better be prepared, he better be good.

As far as artistic advice goes, this is as close to the real thing as it gets. But it can only occur to an artist who can no longer take for granted the energy on which he has unthinkingly relied for most of his life.

Kazan isn’t the only player in the film industry to draw a connection between physical strength—or at least stamina—and the medium’s artistic demands. Guy Hamilton, who directed Goldfinger, once said: “To be a director, all you need is a hide like a rhinoceros—and strong legs, and the ability to think on your feet…Talent is something else.” None other than Christopher Nolan believes so much in the importance of standing that he’s institutionalized it on his film sets, as Mark Rylance recently told The Independent: “He does things like he doesn’t like having chairs on set for actors or bottles of water, he’s very particular…[It] keeps you on your toes, literally.” Walter Murch, meanwhile, noted that a film editor needed “a strong back and arms” to lug around reels of celluloid, which is less of a concern in the days of digital editing, but still worth bearing in mind. Murch famously likes to stand while editing, like a surgeon in the operating room:

Editing is sort of a strange combination of being a brain surgeon and a short-order cook. You’ll never see those guys sitting down on the job. The more you engage your entire body in the process of editing, the better and more balletic the flow of images will be. I might be sitting when I’m reviewing material, but when I’m choosing the point to cut out of a shot, I will always jump out of the chair. A gunfighter will always stand, because it’s the fastest, most accurate way to get to his gun. Imagine High Noon with Gary Cooper sitting in a chair. I feel the fastest, most accurate way to choose the critically important frame I will cut out of a shot is to be standing. I have kind of a gunfighter’s stance.

And as Murch suggests, this applies as much to solitary craftsmen as it does to the social and physical world of the director. Philip Roth, who worked at a lectern, claimed that he paced half a mile for every page that he wrote, while the mathematician Robert P. Langlands reflected: “[My] many hours of physical effort as a youth also meant that my body, never frail but also initially not particularly strong, has lasted much longer than a sedentary occupation might have otherwise permitted.” Standing and walking can be a proxy for mental and moral acuity, as Bertrand Russell implied so memorably:

Our mental makeup is suited to a life of very severe physical labor. I used, when I was younger, to take my holidays walking. I would cover twenty-five miles a day, and when the evening came I had no need of anything to keep me from boredom, since the delight of sitting amply sufficed. But modern life cannot be conducted on these physically strenuous principles. A great deal of work is sedentary, and most manual work exercises only a few specialized muscles. When crowds assemble in Trafalgar Square to cheer to the echo an announcement that the government has decided to have them killed, they would not do so if they had all walked twenty-five miles that day.

Such energy, as Kazan reminds us, isn’t limitless. I still think of myself as relatively young, but I don’t have the raw mental or physical resources that I did fifteen years ago, and I’ve had to come up with various tricks—what a pickup basketball player might call “old-man shit”—to maintain my old levels of productivity. I’ve written elsewhere that certain kinds of thinking are best done sitting down, but there’s also a case to be made for thinking on your feet. Standing is the original power pose, and perhaps the only one likely to have any real effects. And it’s in the late afternoons, both of a working day and of an entire life, that you need to stand and deliver.

The Battle of Dunkirk

During my junior year in college, I saw Christopher Nolan’s Memento at the Brattle Theatre in Cambridge, Massachusetts, for no other reason except that I’d heard it was great. Since then, I’ve seen all of Nolan’s movies on their initial release, which is something I can’t say of any other director. At first, it was because I liked his work and his choices intrigued me, and it only occurred to me around the time of The Dark Knight that I witnessing a career like no other. It’s tempting to compare Nolan to his predecessors, but when you look at his body of work from Memento to Dunkirk, it’s clear that he’s in a category of his own. He’s directed nine theatrical features in seventeen years, all mainstream critical and commercial successes, including some of the biggest movies in recent history. No other director alive comes close to that degree of consistency, at least not at the same level of productivity and scale. Quality and reliability alone aren’t everything, of course, and Nolan pales a bit compared to say, Steven Spielberg, who over a comparable stretch of time went from The Sugarland Express to Hook, with Jaws, Close Encounters, E.T., and the Indiana Jones trilogy along the way, as well as 1941 and Always. By comparison, Nolan can seem studied, deliberate, and remote, and the pockets of unassimilated sentimentality in his work—which I used to assume were concessions to the audience, but now I’m not so sure—only point to how unified and effortless Spielberg is at his best. But the conditions for making movies have also changed over the last four decades, and Nolan has threaded the needle in ways that still amaze me, as I continue to watch his career unfold in real time.

Nolan sometimes reminds me of the immortal Byron the Bulb in Gravity’s Rainbow, of which Thomas Pynchon writes: “Statistically…every n-thousandth light bulb is gonna be perfect, all the delta-q’s piling up just right, so we shouldn’t be surprised that this one’s still around, burning brightly.” He wrote and directed one of the great independent debuts, leveraged it into a career making blockbusters, and slowly became a director from whom audiences expected extraordinary achievements while he was barely out of the first phase of his career. And he keeps doing it. For viewers of college age or younger, he must feel like an institution, while I can’t stop thinking of him as an outlier that has yet to regress to the mean. Nolan’s most significant impact, for better or worse, may lie in the sheer, seductive implausibility of the case study that he presents. Over the last decade or so, we’ve seen a succession of young directors, nearly all of them white males, who, after directing a microbudgeted indie movie, are handed the keys to a huge franchise. This has been taken as an instance of category selection, in which directors who look a certain way are given opportunities that wouldn’t be offered to filmmakers of other backgrounds, but deep down, I think it’s just an attempt to find the next Nolan. If I were an executive at Warner Bros. whose career had overlapped with his, I’d feel toward him what Goethe felt of Napoleon: “[It] produces in me an impression like that produced by the Revelation of St. John the Divine. We all feel there must be something more in it, but we do not know what.” Nolan is the most exciting success story to date of a business model that he defined and that, if it worked, would solve most of Hollywood’s problems, in which independent cinema serves as a farm team for directors who can consistently handle big legacy projects that yield great reviews and box office. And it’s happened exactly once.

You can’t blame Hollywood for hoping that lightning will strike twice, but it’s obvious now that Nolan is like nobody else, and Dunkirk may turn out to be the pivotal film in trying to understand what he represents. I don’t think it’s his best or most audacious movie, but it was certainly the greatest risk, and he seems to have singlehandedly willed it into existence. Artistically, it’s a step forward for a director who sometimes seemed devoted to complexity for its own sake, telling a story of crystalline narrative and geographical clarity with a minimum of dialogue and exposition, with clever tricks with time that lead, for once, to a real emotional payoff. The technical achievement of staging a continuous action climax that runs for most of the movie’s runtime is impressive in itself, and Nolan, who has been gradually preparing for this moment for years, makes it look so straightforward that it’s easy to undervalue it. (Nolan’s great insight here seems to have been that by relying on the audience’s familiarity with the conventions of the war movie, he could lop off the first hour of the story and just tell the second half. Its nonlinear structure, in turn, seems to have been a pragmatic solution to the problem of how to intercut freely between three settings with different temporal and spatial demands, and Nolan strikes me as the one director both to whom it would have occurred and who would have actually been allowed to do it.) On a commercial level, it’s his most brazen attempt, even more than Inception, to see what he could do with the free pass that a director typically gets after a string of hits. And the fact that he succeeded, with a summer box office smash that seems likely to win multiple Oscars, only makes me all the more eager to see what he’ll do next.

It all amounts to the closest film in recent memory to what Omar Sharif once said of Lawrence of Arabia: “If you are the man with the money and somebody comes to you and says he wants to make a film that’s four hours long, with no stars, and no women, and no love story, and not much action either, and he wants to spend a huge amount of money to go film it in the desert—what would you say?” Dunkirk is half as long as Lawrence and consists almost entirely of action, and it isn’t on the same level, but the challenge that it presented to “the man with the money” must have been nearly as great. (Its lack of women, unfortunately, is equally glaring.) In fact, I can think of only one other director who has done anything comparable. I happened to see Dunkirk a few weeks after catching 2001: A Space Odyssey on the big screen, and as I watched the former movie last night, it occurred to me that Nolan has pulled off the most convincing Kubrick impression that any of us have ever seen. You don’t become the next Kubrick by imitating him, as Nolan did to some extent in Interstellar, but by figuring out new ways to tell stories using all the resources of the cinema, and somehow convincing a studio to fund the result. In both cases, the studio was Warner Bros., and I wonder if executives with long memories see Nolan as a transitional figure between Kubrick and the needs of the DC Extended Universe. It’s a difficult position for any director to occupy, and it may well prevent Nolan from developing along more interesting lines that his career might otherwise have taken. His artistic gambles, while considerable, are modest compared to even Barry Lyndon, and his position at the center of the industry can only discourage him from running the risk of being difficult or alienating. But I’m not complaining. Dunkirk is the story of a retreat, but it’s also the latest chapter in the life of a director who just can’t stop advancing.

Gatsby’s fortune and the art of ambiguity

Note: I’m taking a short break this week, so I’ll be republishing a few posts from earlier in this blog’s run. This post originally appeared, in a slightly different form, on July 17, 2015.

In November 1924, the editor Maxwell Perkins received the manuscript of a novel tentatively titled Trimalchio in West Egg. He loved the book—he called it “extraordinary” and “magnificent”—but he also had a perceptive set of notes for its author. Here are a few of them:

Among a set of characters marvelously palpable and vital—I would know Tom Buchanan if I met him on the street and would avoid him—Gatsby is somewhat vague. The reader’s eyes can never quite focus upon him, his outlines are dim. Now everything about Gatsby is more or less a mystery, i.e. more or less vague, and this may be somewhat of an artistic intention, but I think it is mistaken. Couldn’t he be physically described as distinctly as the others, and couldn’t you add one or two characteristics like the use of that phrase “old sport”—not verbal, but physical ones, perhaps…

The other point is also about Gatsby: his career must remain mysterious, of course…Now almost all readers numerically are going to feel puzzled by his having all this wealth and are going to feel entitled to an explanation. To give a distinct and definite one would be, of course, utterly absurd. It did occur to me, thought, that you might here and there interpolate some phrases, and possibly incidents, little touches of various kinds, that would suggest that he was in some active way mysteriously engaged.

The novel, of course, ultimately appeared under the title The Great Gatsby, and before it was published, F. Scott Fitzgerald took many of the notes from Perkins to heart, adding more descriptive material on Gatsby himself—along with several repetitions of the phrase “old sport”—and the sources of his mysterious fortune. Like Tay Hohoff, whose work on To Kill a Mockingbird has received greater recognition in recent years, or even John W. Campbell, Perkins was the exemplar of the editor as shaper, providing valued insight and active intervention for many of the major writers of his generation: Fitzgerald, Hemingway, Wolfe. But my favorite part of this story lies in Fitzgerald’s response, which I think is one of the most extraordinary glimpses into craft we have from any novelist:

I myself didn’t know what Gatsby looked like or was engaged in and you felt it. If I’d known and kept it from you you’d have been too impressed with my knowledge to protest. This is a complicated idea but I’m sure you’ll understand. But I know now—and as a penalty for not having known first, in other words to make sure, I’m going to tell more.

Which is only to say that there’s a big difference between what an author deliberately withholds and what he doesn’t know himself. And an intelligent reader, like Perkins, will sense it.

And it has important implications for the way we create our characters. I’ve never been a fan of the school that advocates working out every detail of a character’s background, from her hobbies to her childhood pets: the questionnaires and worksheets that spring up around this impulse can all too easily turn into an excuse for procrastination. My own sense of character is closer to what D’Arcy Wentworth Thompson describes in On Growth and Form, in which an animal’s physical shape is determined largely by the outside pressures to which it is subjected. Plot emerges from character, yes, but there’s also a sense in which character emerges from plot: these men and women are distinguished primarily by the fact that they’re the only people in the world to whom these particular events could happen. When I combine this with my natural distrust of backstory, I’ll frequently find that there are important things about my characters I don’t know myself, even after I’ve lived with them for years. There can even be something a little false about keeping the past constantly present in a character’s mind, as we often see in “realistic” fiction: even if we’re all the sum of our childhood experiences, in practice, we reveal more about ourselves in how we react to the pattern of forces in our lives at any given moment, and the resulting actions have a logic that can be worked out independently, as long as the situation is honestly developed.

But that doesn’t apply to issues, like the sources of Gatsby’s fortune, in which the reader’s curiosity might be reasonably aroused. If you’re going to hint at something, you’d better have a good idea of the answer, even if you don’t plan on sharing it. This applies especially to stories that generate a deliberate ambiguity, as Chris Nolan says of the ending of Inception:

Interviewer: I know that you’re not going to tell me [what the ending means], but I would have guessed that really, because the audience fills in the gaps, you yourself would say, “I don’t have an answer.”

Nolan: Oh no, I’ve got an answer.

Interviewer: You do?!

Nolan: Oh yeah. I’ve always believed that if you make a film with ambiguity, it needs to be based on a sincere interpretation. If it’s not, then it will contradict itself, or it will be somehow insubstantial and end up making the audience feel cheated.

Ambiguity, as I’ve said elsewhere, is best created out of a network of specifics with one crucial piece removed. That specificity requires a great deal of knowledge on the author’s part, perhaps more here than anywhere else. And as Fitzgerald notes, if you do it properly, they’ll be too impressed by your knowledge to protest—or they’ll protest in all the right ways.

The strange loop of Westworld

In last week’s issue of The New Yorker, the critic Emily Nussbaum delivers one of the most useful takes I’ve seen so far on Westworld. She opens with many of the same points that I made after the premiere—that this is really a series about storytelling, and, in particular, about the challenges of mounting an expensive prestige drama on a premium network during the golden age of television. Nussbaum describes her own ambivalence toward the show’s treatment of women and minorities, and she concludes:

This is not to say that the show is feminist in any clear or uncontradictory way—like many series of this school, it often treats male fantasy as a default setting, something that everyone can enjoy. It’s baffling why certain demographics would ever pay to visit Westworld…The American Old West is a logical fantasy only if you’re the cowboy—or if your fantasy is to be exploited or enslaved, a desire left unexplored…So female customers get scattered like raisins into the oatmeal of male action; and, while the cast is visually polyglot, the dialogue is color-blind. The result is a layer of insoluble instability, a puzzle that the viewer has to work out for herself: Is Westworld the blinkered macho fantasy, or is that Westworld? It’s a meta-cliffhanger with its own allure, leaving us only one way to find out: stay tuned for next week’s episode.

I agree with many of her reservations, especially when it comes to race, but I think that she overlooks or omits one important point: conscious or otherwise, it’s a brilliant narrative strategy to make a work of art partially about the process of its own creation, which can add a layer of depth even to its compromises and mistakes. I’ve drawn a comparison already to Mad Men, which was a show about advertising that ended up subliminally criticizing its own tactics—how it drew viewers into complex, often bleak stories using the surface allure of its sets, costumes, and attractive cast. If you want to stick with the Nolan family, half of Chris’s movies can be read as commentaries on themselves, whether it’s his stricken identification with the Joker as the master of ceremonies in The Dark Knight or his analysis of his own tricks in The Prestige. Inception is less about the construction of dreams than it is about making movies, with characters who stand in for the director, the producer, the set designer, and the audience. And perhaps the greatest cinematic example of them all is Vertigo, in which Scotty’s treatment of Madeline is inseparable from the use that Hitchcock makes of Kim Novak, as he did with so many other blonde leading ladies. In each case, we can enjoy the story on its own merits, but it gains added resonance when we think of it as a dramatization of what happened behind the scenes. It’s an approach that is uniquely forgiving of flawed masterpieces, which comment on themselves better than any critic can, until we wonder about the extent to which they’re aware of their own limitations.

And this kind of thing works best when it isn’t too literal. Movies about filmmaking are often disappointing, either because they’re too close to their subject for the allegory to resonate or because the movie within the movie seems clumsy compared to the subtlety of the larger film. It’s why Being John Malkovich is so much more beguiling a statement than the more obvious Adaptation. In television, the most unfortunate recent example is UnREAL. You’d expect that a show that was so smart about the making of a reality series would begin to refer intriguingly to itself, and it did, but not in a good way. Its second season was a disappointment, evidently because of the same factors that beset its fictional show Everlasting: interference from the network, conceptual confusion, tensions between producers on the set. It seemed strange that UnREAL, of all shows, could display such a lack of insight into its own problems, but maybe it isn’t so surprising. A good analogy needs to hold us at arm’s length, both to grant some perspective and to allow for surprising discoveries in the gaps. The ballet company in The Red Shoes and the New York Inquirer in Citizen Kane are surrogates for the movie studio, and both films become even more interesting when you realize how much the lead character is a portrait of the director. Sometimes it’s unclear how much of this is intentional, but this doesn’t hurt. So much of any work of art is out of your control that you need to find an approach that automatically converts your liabilities into assets, and you can start by conceiving a premise that encourages the viewer or reader to play along at home.

Which brings us back to Westworld. In her critique, Nussbaum writes: “Westworld [is] a come-hither drama that introduces itself as a science-fiction thriller about cyborgs who become self-aware, then reveals its true identity as what happens when an HBO drama struggles to do the same.” She implies that this is a bug, but it’s really a feature. Westworld wouldn’t be nearly as interesting if it weren’t being produced with this cast, on this network, and on this scale. We’re supposed to be impressed by the time and money that have gone into the park—they’ve spared no expense, as John Hammond might say—but it isn’t all that different from the resources that go into a big-budget drama like this. In the most recent episode, “Dissonance Theory,” the show invokes the image of the maze, as we might expect from a series by a Nolan brother: get to the center to the labyrinth, it says, and you’ve won. But it’s more like what Douglas R. Hofstadter describes in I Am a Strange Loop:

What I mean by “strange loop” is—here goes a first stab, anyway—not a physical circuit but an abstract loop in which, in the series of stages that constitute the cycling-around, there is a shift from one level of abstraction (or structure) to another, which feels like an upwards movement in a hierarchy, and yet somehow the successive “upward” shifts turn out to give rise to a closed cycle. That is, despite one’s sense of departing ever further from one’s origin, one winds up, to one’s shock, exactly where one had started out.

This neatly describes both the park and the series. And it’s only through such strange loops, as Hofstadter has long argued, that any complex system—whether it’s the human brain, a robot, or a television show—can hope to achieve full consciousness.

The test of tone

Note: I’m on vacation this week, so I’ll be republishing a few of my favorite posts from earlier in this blog’s run. This post originally appeared, in a slightly different form, on April 22, 2014.

Tone, as I’ve mentioned before, can be a tricky thing. On the subject of plot, David Mamet writes: “Turn the thing around in the last two minutes, and you can live quite nicely. Turn it around in the last ten seconds and you can buy a house in Bel Air.” And if you can radically shift tones within a single story and still keep the audience on board, you can end up with even more. If you look at the short list of the most exciting directors around—Paul Thomas Anderson, David O. Russell, Quentin Tarantino, David Fincher, the Coen Brothers—you find that what most of them have in common is the ability to alter tones drastically from scene to scene, with comedy giving way unexpectedly to violence or pathos. (A big exception here is Christopher Nolan, who seems happiest when operating within a fundamentally serious tonal range. It’s a limitation, but one we’re willing to accept because Nolan is so good at so many other things. Take away those gifts, and you end up with Transcendence.) Tonal variation may be the last thing a director masters, and it often only happens after a few films that keep a consistent tone most of the way through, however idiosyncratic it may be. The Coens started with Blood Simple, then Raising Arizona, and once they made Miller’s Crossing, they never had to look back.

The trouble with tone is that it imposes tremendous switching costs on the audience. As Tony Gilroy points out, during the first ten minutes of a movie, a viewer is making a lot of decisions about how seriously to take the material. Each time the level of seriousness changes gears, whether upward or downward, it demands a corresponding moment of consolidation, which can be exhausting. For a story that runs two hours or so, more than a few shifts in tone can alienate viewers to no end. You never really know where you stand, or whether you’ll be watching the same movie ten minutes from now, so your reaction is often how Roger Ebert felt upon watching Pulp Fiction for the first time: “Seeing this movie last May at the Cannes Film Festival, I knew it was either one of the year’s best films, or one of the worst.” (The outcome is also extremely subjective. I happen to think that Vanilla Sky is one of the most criminally underrated movies of the last two decades—few other mainstream films have accommodated so many tones and moods—but I’m not surprised that so many people hate it.) It also annoys marketing departments, who can’t easily explain what the movie is about; it’s no accident that one of the worst trailers I can recall was for In Bruges, which plays with tone as dexterously as any movie in recent memory.

As a result, tone is another element in which television has considerable advantages. Instead of two hours, a show ideally has at least one season, maybe more, to play around with tone, and the number of potential switching points is accordingly increased. A television series is already more loosely organized than a movie, which allows it to digress and go off on promising tangents, and we’re used to being asked to stop and start from week to week, so we’re more forgiving of departures. That said, this rarely happens all at once; like a director’s filmography, a show often needs a season or two to establish its strengths before it can go exploring. When we think back to a show’s pivotal episodes—the ones in which the future of the series seemed to lock into place—they’re often installments that discovered a new tone that worked within the rules that the show had laid down. Community was never the same after “Modern Warfare,” followed by “Abed’s Uncontrollable Christmas,” demonstrated how much it could push its own reality while still remaining true to its characters, and The X-Files was altered forever by Darin Morgan’s “Humbug,” which taught the show how far it could kid itself while probing into ever darker places.

At its best, this isn’t just a matter of having a “funny” episode of a dramatic series, or a very special episode of a sitcom, but of building a body of narrative that can accommodate surprise. One of the great pleasures of watching Hannibal lay in how it learned to acknowledge its own absurdity while drawing the noose ever tighter, which only happens after a show has enough history for it to engage in a dialogue with itself. Much the same happened to Breaking Bad, which had the broadest tonal range imaginable: it was able to move between borderline slapstick and the blackest of narrative developments because it could look back and reassure itself that it had already done a good job with both. (Occasionally, a show will emerge with that kind of tone in mind from the beginning. Fargo remains the most fascinating drama on television in large part because it draws its inspiration from one of the most virtuoso experiments with tone in movie history.) If it works, the result starts to feel like life itself, which can’t be confined easily within any one genre. Maybe that’s because learning to master tone is like putting together the pieces of one’s own life: first you try one thing, then something else, and if you’re lucky, you’ll find that they work well side by side.

The Coco Chanel rule

“Before you leave the house,” the fashion designer Coco Chanel is supposed to have said, “look in the mirror and remove one accessory.” As much as I like it, I’m sorry to say that this quote is most likely apocryphal: you see it attributed to Chanel everywhere, but without the benefit of an original source, which implies that it’s one of those pieces of collective wisdom that have attached themselves parasitically to a famous name. Still, it’s valuable advice. It’s usually interpreted, correctly enough, as a reminder that less is more, but I prefer to think of it as a statement about revision. The quote isn’t about reaching simplicity from the ground up, but about taking something and improving it by subtracting one element, like the writing rule that advises you to cut ten percent from every draft. And what I like the most about it is that its moment of truth arrives at the very last second, when you’re about to leave the house. That final glance in the mirror, when it’s almost too late to make additional changes, is often when the true strengths and weaknesses of your decisions become clear, if you’re smart enough to distinguish it from the jitters. (As Jeffrey Eugenides said to The Paris Review: “Usually I’m turning the book in at the last minute. I always say it’s like the Greek Olympics—’Hope the torch lights.'”)

But which accessory should you remove? In the indispensable book Behind the Seen, the editor Walter Murch gives us an important clue, using an analogy from filmmaking:

In interior might have four different sources of light in it: the light from the window, the light from the table lamp, the light from the flashlight that the character is holding, and some other remotely sourced lights. The danger is that, without hardly trying, you can create a luminous clutter out of all that. There’s a shadow over here, so you put another light on that shadow to make it disappear. Well, that new light casts a shadow in the other direction. Suddenly there are fifteen lights and you only want four.

As a cameraman what you paradoxically do is have the gaffer turn off the main light, because it is confusing your ability to really see what you’ve got. Once you do that, you selectively turn off some of the lights and see what’s left. And you discover that, “OK, those other three lights I really don’t need at all—kill ’em.” But it can also happen that you turn off the main light and suddenly, “Hey, this looks great! I don’t need that main light after all, just these secondary lights. What was I thinking?”

This principle, which Murch elsewhere calls “blinking the key,” implies that you should take away the most important piece, or the accessory that you thought you couldn’t live without.

This squares nicely with a number of principles that I’ve discussed here before. I once said that ambiguity is best created out of a network of specifics with one crucial piece removed, and when you follow the Chanel rule, on a deeper level, the missing accessory is still present, even after you’ve taken it off. The remaining accessories were presumably chosen with it in mind, and they preserve its outlines, resulting in a kind of charged negative space that binds the rest together. This applies to writing, too. “The Cask of Amontillado” practically amounts to a manual on how to wall up a man alive, but Poe omits the one crucial detail—the reason for Montresor’s murderous hatred—that most writers would have provided up front, and the result is all the more powerful. Shakespeare consistently leaves out key explanatory details from his source material, which renders the behavior of his characters more mysterious, but no less concrete. And the mumblecore filmmaker Andrew Bujalski made a similar point a few years ago to The New York Times Magazine: “Write out the scene the way you hear it in your head. Then read it and find the parts where the characters are saying exactly what you want/need them to say for the sake of narrative clarity (e.g., ‘I’ve secretly loved you all along, but I’ve been too afraid to tell you.’) Cut that part out. See what’s left. You’re probably close.”

This is a piece of advice that many artists could stand to take to heart, especially if they’ve been blessed with an abundance of invention. I like Interstellar, for instance, but I have a hunch that it would have been an even stronger film if Christopher Nolan had made a few cuts. If he had removed Anne Hathaway’s speech on the power of love, for instance, the same point would have come across in the action, but more subtly, assuming that the rest of the story justified its inclusion in the first place. (Of course, every film that Nolan has ever made strives valiantly to strike a balance between action and exposition, and in this case, it stumbled a little in the wrong direction. Interstellar is so openly indebted to 2001 that I wish it had taken a cue from that movie’s script, in which Kubrick and Clarke made the right strategic choice by minimizing the human element wherever possible.) What makes the Chanel rule so powerful is that when you glance in the mirror on your way out the door, what catches your eye first is likely to be the largest, flashiest, or most obvious component, which often adds the most by its subtraction. It’s the accessory that explains too much, or draws attention to itself, rather than complementing the whole, and by removing it, we’re consciously saying no to what the mind initially suggests. As Chanel is often quoted as saying: “Elegance is refusal.” And she was right—even if it was really Diana Vreeland who said it.

“And what does that name have to do with this?”

Note: This post is the thirtieth installment in my author’s commentary for Eternal Empire, covering Chapter 29. You can read the previous installments here.

Earlier this week, in response to a devastating article in the New York Times on the allegedly crushing work environment in Amazon’s corporate offices, Jeff Bezos sent an email to employees that included the following statement:

[The article] claims that our intentional approach is to create a soulless, dystopian workplace where no fun is had and no laughter is heard. Again, I don’t recognize this Amazon and I very much hope you don’t, either…I strongly believe that anyone working in a company that really is like the one described in the [Times] would be crazy to stay. I know I would leave such a company.

Predictably, the email resulted in numerous headlines along the lines of “Jeff Bezos to Employees: You Don’t Work in a Dystopian Hellscape, Do You?” Bezos, a very smart guy, should have seen it coming. As Richard Nixon learned a long time ago, whenever you tell people that you aren’t a crook, you’re really raising the possibility that you might be. If you’re concerned about the names that your critics might call you, the last thing you want to do is put words in their mouths—it’s why public relations experts advise their clients to avoid negative language, even in the form of a denial—and saying that Amazon isn’t a soulless, dystopian workplace is a little like asking us not to think of an elephant.

Writers have recognized the negative power of certain loaded terms for a long time, and many works of art go out of their way to avoid such words, even if they’re central to the story. One of my favorite examples is the film version of The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo. Coming off Seven and Zodiac, David Fincher didn’t want to be pigeonholed as a director of serial killer movies, so the dialogue exclusively uses the term “serial murderer,” although it’s doubtful how effective this was. Along the same lines, Christopher Nolan’s superhero movies are notably averse to calling their characters by their most famous names: The Dark Knight Rises never uses the name “Catwoman,” while Man of Steel, which Nolan produced, avoids “Superman,” perhaps following the example of Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns, which indulges in similar circumlocutions. Robert Towne’s script for Greystoke never calls its central character “Tarzan,” and The Walking Dead uses just about every imaginable term for its creatures aside from “zombie,” for reasons that creator Robert Kirkman explains:

One of the things about this world is that…they’re not familiar with zombies, per se. This isn’t a world [in which] the Romero movies exist, for instance, because we don’t want to portray it that way…They’ve never seen this in pop culture. This is a completely new thing for them.

Kirkman’s reluctance to call anything a zombie, which has inspired an entire page on TV Tropes dedicated to similar examples, is particularly revealing. A zombie movie can’t use that word because an invasion of the undead needs to feel like something unprecedented, and falling back on a term we know conjures up all kinds of pop cultural connotations that an original take might prefer to avoid. In many cases, avoiding particular words subtly encourages us treat the story on its own terms. In The Godfather, the term “Mafia” is never uttered—an aversion, incidentally, not shared by the original novel, the working title of which was actually Mafia. This quietly allows us to judge the Corleones according to the rules of their own closed world, and it circumvents any real reflection about what the family business actually involves. (According to one famous story, the mobster Joseph Colombo paid a visit to producer Al Ruddy, demanding that the word be struck from the script as a condition for allowing the movie to continue. Ruddy, who knew that the screenplay only used the word once, promptly agreed.) The Godfather Part II is largely devoted to blowing up the first movie’s assumptions, and when the word “Mafia” is uttered at a senate hearing, it feels like the real world intruding on a comfortable fantasy. And the moment wouldn’t be as effective if the first installment hadn’t been as diligent about avoiding the term, allowing it to build a new myth in its place.

While writing Eternal Empire, I found myself confronting a similar problem. In this case, the offending word was “Shambhala.” As I’ve noted before, I decided early on that the third novel in the series would center on the Shambhala myth, a choice I made as soon as I stumbled across an excerpt from Rachel Polonsky’s Molotov’s Magic Lantern, in which she states that Vladimir Putin had taken a particular interest in the legend. A little research, notably in Andrei Znamenski’s Red Shambhala, confirmed that the periodic attempts by Russia to confirm the existence of that mythical kingdom, carried out in an atmosphere of espionage and spycraft in Central Asia, was a rich vein of material. The trouble was that the word “Shambhala” itself was so loaded with New Age connotations that I’d have trouble digging my way out from under it: a quick search online reveals that it’s the name of a string of meditation centers, a music festival, and a spa with its own line of massage oils, none of which is exactly in keeping with the tone that I was trying to evoke. My solution, predictably, was to structure the whole plot around the myth of Shambhala while mentioning it as little as possible: the name appears perhaps thirty times across four hundred pages. (The mythological history of Shambhala is treated barely at all, and most of the references occur in discussions of the real attempts by Russian intelligence to discover it.) The bulk of those references appear here, in Chapter 29, and I cut them all down as much as possible, focusing on the bare minimum I needed for Maddy to pique Tarkovsky’s interest. I probably could have cut them even further. But as it stands, it’s more or less enough to get the story to where it needs to be. And it doesn’t need to be any longer than it is…

Gatsby’s fortune and the art of ambiguity

In November 1924, the editor Maxwell Perkins received the manuscript of a novel tentatively titled Trimalchio in West Egg. He loved the book—he called it “extraordinary” and “magnificent”—but he also had a perceptive set of notes for its author. Here are a few of them:

Among a set of characters marvelously palpable and vital—I would know Tom Buchanan if I met him on the street and would avoid him—Gatsby is somewhat vague. The reader’s eyes can never quite focus upon him, his outlines are dim. Now everything about Gatsby is more or less a mystery, i.e. more or less vague, and this may be somewhat of an artistic intention, but I think it is mistaken. Couldn’t he be physically described as distinctly as the others, and couldn’t you add one or two characteristics like the use of that phrase “old sport”—not verbal, but physical ones, perhaps…

The other point is also about Gatsby: his career must remain mysterious, of course…Now almost all readers numerically are going to feel puzzled by his having all this wealth and are going to feel entitled to an explanation. To give a distinct and definite one would be, of course, utterly absurd. It did occur to me, thought, that you might here and there interpolate some phrases, and possibly incidents, little touches of various kinds, that would suggest that he was in some active way mysteriously engaged.

The novel, of course, ultimately appeared under the title The Great Gatsby, and before it was published, F. Scott Fitzgerald took many of the notes from Perkins to heart, adding more descriptive material on Gatsby himself—along with several repetitions of the phrase “old sport”—and the sources of his mysterious fortune. Like Tay Hohoff, whose work on To Kill a Mockingbird has recently come back into the spotlight, Perkins was the exemplar of the editor as shaper, providing valued insight and active intervention for many of the major writers of his generation: Fitzgerald, Hemingway, Wolfe. But my favorite part of this story lies in Fitzgerald’s response, which I think is one of the most extraordinary glimpses into craft we have from any novelist:

I myself didn’t know what Gatsby looked like or was engaged in and you felt it. If I’d known and kept it from you you’d have been too impressed with my knowledge to protest. This is a complicated idea but I’m sure you’ll understand. But I know now—and as a penalty for not having known first, in other words to make sure, I’m going to tell more.

Which is only to say that there’s a big difference between what an author deliberately withholds and what he doesn’t know himself. And an intelligent reader, like Perkins, will sense it.

And it has important implications for the way we create our characters. I’ve never been a fan of the school that advocates working out every detail of a character’s background, from her hobbies to her childhood pets: the questionnaires and worksheets that spring up around this impulse always seem like an excuse for procrastination. My own sense of character is closer to what D’Arcy Wentworth Thompson describes in On Growth and Form, in which an animal’s physical shape is determined largely by the outside pressures to which it is subjected. Plot emerges from character, yes, but there’s also a sense in which character emerges from plot: these men and women are distinguished primarily by the fact that they’re the only people in the world to whom these particular events could happen. When I combine this with my natural distrust of backstory, even if I’m retreating from this a bit, I’ll often find that there are important things about my characters I don’t know myself, even after I’ve lived with them for years. There can even be something a little false about keeping the past constantly present in a character’s mind, as we see in so much “realistic” fiction: even if we’re all the sum of our childhood experiences, in practice, we reveal more about ourselves in how we react to the pattern of forces in our lives at the moment, and our actions have a logic that can be worked out independently, as long as the situation is honestly developed.

But that doesn’t apply to issues, like the sources of Gatsby’s fortune, in which the reader’s curiosity might be reasonably aroused. If you’re going to hint at something, you’d better have a good idea of the answer, even if you don’t plan on sharing it. This applies especially to stories that generate a deliberate ambiguity, as Chris Nolan says of the ending of Inception:

Interviewer: I know that you’re not going to tell me [what the ending means], but I would have guessed that really, because the audience fills in the gaps, you yourself would say, “I don’t have an answer.”

Nolan: Oh no, I’ve got an answer.

Interviewer: You do?!

Nolan: Oh yeah. I’ve always believed that if you make a film with ambiguity, it needs to be based on a sincere interpretation. If it’s not, then it will contradict itself, or it will be somehow insubstantial and end up making the audience feel cheated.

Ambiguity, as I’ve said elsewhere, is best created out of a network of specifics with one crucial piece removed. That specificity requires a great deal of knowledge on the author’s part, perhaps more here than anywhere else. And as Fitzgerald notes, if you do it properly, they’ll be too impressed by your knowledge to protest—or they’ll protest in all the right ways.

My ten great movies #10: Inception

Note: Four years ago, I published a series of posts here about my ten favorite movies. Since then, the list has evolved, as all such rankings do, with a few new titles and a reshuffling of the survivors, so it seems like as good a time as any to revisit it now.

Five years after its release, when we think of Inception, what we’re likely to remember first—aside from its considerable merits as entertainment—is its apparent complexity. With five or more levels of reality and a set of rules being explained to us, as well as to the characters, in parallel with breathless action, it’s no wonder that its one big laugh comes at Ariadne’s bewildered question: “Whose subconscious are we going into?” It’s a line that gives us permission to be lost. Yet it’s all far less confusing than it might have been, thanks largely to the work of editor Lee Smith, whose lack of an Oscar nomination, in retrospect, seems like an even greater scandal than Nolan’s snub as Best Director. This is one of the most comprehensively organized movies ever made. Yet a lot of credit is also due to Nolan’s script, and in particular to the shrewd choices it makes about where to walk back its own complications. As I’ve noted before, once the premise has been established, the action unfolds more or less as we’ve been told it will: there isn’t the third-act twist or betrayal that similar heist movies, or even Memento, have taught us to expect. Another nudge would cause it all to collapse.

It’s also in part for the sake of reducing clutter that the dream worlds themselves tend to be starkly realistic, while remaining beautiful and striking. A director like Terry Gilliam might have turned each level into a riot of production design, and although the movie’s relative lack of surrealism has been taken as a flaw, it’s really more of a strategy for keeping the clean lines of the story distinct. The same applies to the characters, who, with the exception of Cobb, are defined mostly by their roles in the action. Yet they’re curiously compelling, perhaps because we respond so instinctively to stories of heists and elaborate teamwork. I admire Interstellar, but I can’t say I need to spend another three hours in the company of its characters, while Inception leaves me wanting more. This is also because its premise is so rich: it hints at countless possible stories, but turns itself into a closed circle that denies any prospect of a sequel. (It’s worth noting, too, how ingenious the device of the totem really is, with the massive superstructure of one of the largest movies ever made coming to rest on the axis of a single trembling top.) And it’s that unresolved tension, between a universe of possibilities and a remorseless cut to black, that gives us the material for so many dreams.

Tomorrow: The greatest story in movies.

The poster problem

Three years ago, while reviewing The Avengers soon after its opening weekend, I made the following remarks, which seem to have held up fairly well:

This is a movie that comes across as a triumph more of assemblage and marketing than of storytelling: you want to cheer, not for the director or the heroes, but for the executives at Marvel who brought it all off. Joss Whedon does a nice, resourceful job of putting the pieces together, but we’re left with the sense of a director gamely doing his best with the hand he’s been dealt, which is an odd thing to say for a movie that someone paid $200 million to make. Whedon has been saddled with at least two heroes too many…so that a lot of the film, probably too much, is spent slotting all the components into place.

If the early reactions to Age of Ultron are any indication, I could copy and paste this text and make it the centerpiece of a review of any Avengers movie, past or future. This isn’t to say that the latest installment—which I haven’t seen—might not be fine in its way. But even the franchise’s fans, of which I’m not really one, seem to admit that much of it consists of Whedon dealing with all those moving parts, and the extent of your enjoyment depends largely on how well you feel he pulls it off.

Whedon himself has indicated that he has less control over the process than he’d like. In a recent interview with Mental Floss, he says:

But it’s difficult because you’re living in franchise world—not just Marvel, but in most big films—where you can’t kill anyone, or anybody significant. And now I find myself with a huge crew of people and, although I’m not as bloodthirsty as some people like to pretend, I think it’s disingenuous to say we’re going to fight this great battle, but there’s not going to be any loss. So my feeling in these situations with Marvel is that if somebody has to be placed on the altar and sacrificed, I’ll let you guys decide if they stay there.

Which, when you think about it, is a startling statement to hear from one of Hollywood’s most powerful directors. But it accurately describes the situation. Any Avengers movie will always feel less like a story in itself than like a kind of anomalous weather pattern formed at the meeting point of several huge fronts: the plot, such as it is, emerges in the transition zone, and it’s dwarfed by the masses of air behind it. Marvel has made a specialty of exceeding audience expectations just ever so slightly, and given the gigantic marketing pressures involved, it’s a marvel that it works as well as it does.

It’s fair to ask, in fact, whether any movie with that poster—with no fewer than eight names above the title, most belonging to current or potential franchise bearers—could ever be more than an exercise in crowd control. In fact, there’s a telling counterexample, and it looks, as I’ve said elsewhere, increasingly impressive with time: Christopher Nolan’s Inception. As the years pass, Inception remains a model movie in many respects, but particularly when it comes to the problem of managing narrative complexity. Nolan picks his battles in fascinating ways: he’s telling a nested story with five or more levels of reality, and like Thomas Pynchon, he selectively simplifies the material wherever he can. There’s the fact, for instance, that once the logic of the plot has been explained, it unfolds more or less as we expect, without the twist or third-act betrayal that we’ve been trained to anticipate in most heist movies. The characters, with the exception of Cobb, are defined largely by their surfaces, with a specified role and a few identifying traits. Yet they don’t come off as thin or underdeveloped, and although the poster for Inception is even more packed than that for Age of Ultron, with nine names above the title, we don’t feel that the movie is scrambling to find room for everyone.

And a glance at the cast lists of these movies goes a long way toward explaining why. The Avengers has about fifty speaking parts; Age of Ultron has sixty; and Inception, incredibly, has only fifteen or so. Inception is, in fact, a remarkably underpopulated movie: aside from its leading actors, only a handful of other faces ever appear. Yet we don’t particularly notice this while watching. In all likelihood, there’s a threshold number of characters necessary for a movie to seem fully peopled—and to provide for enough interesting pairings—and any further increase doesn’t change our perception of the whole. If that’s the case, then it’s another shrewd simplification by Nolan, who gives us exactly the number of characters we need and no more. The Avengers movies operate on a different scale, of course: a movie full of superheroes needs some ordinary people for contrast, and there’s a greater need for extras when the stage is as big as the universe. (On paper, anyway. In practice, the stakes in a movie like this are always going to remain something of an abstraction, since we have eight more installments waiting in the wings.) But if Whedon had been more ruthless at paring down his cast at the margins, we might have ended up with a series of films that seemed, paradoxically, larger: each hero could have expanded to fill the space he or she deserved, rather than occupying one corner of a masterpiece of Photoshop.

Left brain, right brain, samurai brain

The idea that the brain can be neatly divided into its left and right hemispheres, one rational, the other intuitive, has been largely debunked, but that doesn’t make it any less useful as a metaphor. You could play an instructive game, for instance, by placing movie directors on a spectrum defined by, say, Kubrick and Altman as the quintessence of left-brained filmmaking and its right-brained opposite, and although such distinctions may be artificial, they can generate their own kind of insight. Christopher Nolan, for one, strikes me as a fundamentally left-brained director who makes a point of consciously willing himself into emotion. (Citing some of the cornier elements of Interstellar, the writer Ta-Nehisi Coates theorizes that they were imposed by the studio, but I think it’s more likely that they reflect Nolan’s own efforts, not always successful, to nudge the story into recognizably human places. He pulled it off beautifully in Inception, but it took him ten years to figure out how.) And just as Isaiah Berlin saw Tolstoy as a fox who wanted to be a hedgehog, many of the recent films of Wong Kar-Wai feel like the work of a right-brained director trying to convince himself that the left hemisphere is where he belongs.