Posts Tagged ‘Esquire’

Ringing in the new

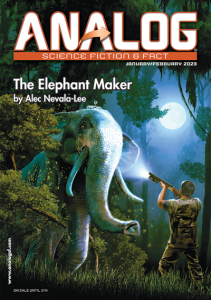

By any measure, I had a pretty productive year as a writer. My book Inventor of the Future: The Visionary Life of Buckminster Fuller was released after more than three years of work, and the reception so far has been very encouraging—it was named a New York Times Book Review Editors’ Choice, an Economist best book of the year, and, wildest of all, one of Esquire‘s fifty best biographies of all time. (My own vote would go to David Thomson’s Rosebud, his fantastically provocative biography of Orson Welles.) On the nonfiction front, I rounded out the year with pieces in Slate (on the misleading claim that Fuller somehow anticipated the principles of cryptocurrency) and the New York Times (on the remarkable British writer R.C. Sherriff and his wonderful novel The Hopkins Manuscript). Best of all, the latest issue of Analog features my 36,000-word novella “The Elephant Maker,” a revised and updated version of an unpublished novel that I started writing in my twenties. Seeing it in print, along with Inventor of the Future, feels like the end of an era for me, and I’m not sure what the next chapter will bring. But once I know, you’ll hear about it here first.

The paper of record

One of my favorite conventions in suspense fiction is the trope known as Authentication by Newspaper. It’s the moment in a movie, novel, or television show—and sometimes even in reality—when the kidnapper sends a picture of the victim holding a copy of a recent paper, with the date and headline clearly visible, as a form of proof of life. (You can also use it with piles of illicit cash, to prove that you’re ready to send payment.) The idea frequently pops up in such movies as Midnight Run and Mission: Impossible 2, and it also inspired a classic headline from The Onion: “Report: Majority Of Newspapers Now Purchased By Kidnappers To Prove Date.” It all depends on the fact that a newspaper is a datable object that is widely available and impossible to fake in advance, which means that it can be used to definitively establish the earliest possible day in which an event could have taken place. And you can also use the paper to verify a past date in subtler ways. A few weeks ago, Motherboard had a fascinating article on a time-stamping service called Surety, which provides the equivalent of a dated seal for digital documents. To make it impossible to change the date on one of these files, every week, for more than twenty years, Surety has generated a public hash value from its internal client database and published it in the classified ad section of the New York Times. As the company notes: “This makes it impossible for anyone—including Surety—to backdate timestamps or validate electronic records that were not exact copies of the original.”

I was reminded of all this yesterday, after the Times posted an anonymous opinion piece titled “I Am Part of the Resistance Inside the Trump Administration.” The essay, which the paper credits to “a senior official,” describes what amounts to a shadow government within the White House devoted to saving the president—and the rest of the country—from his worst impulses. And while the author may prefer to remain nameless, he certainly doesn’t suffer from a lack of humility:

Many of the senior officials in [Trump’s] own administration are working diligently from within to frustrate parts of his agenda and his worst inclinations. I would know. I am one of them…It may be cold comfort in this chaotic era, but Americans should know that there are adults in the room. We fully recognize what is happening. And we are trying to do what’s right even when Donald Trump won’t.

The result, he claims, is “a two-track presidency,” with a group of principled advisors doing their best to counteract Trump’s admiration for autocrats and contempt for international relations: “This isn’t the work of the so-called deep state. It’s the work of the steady state.” He even reveals that there was early discussion among cabinet members of using the Twenty-Fifth Amendment to remove Trump from office, although it was scuttled by concern of precipitating a crisis somehow worse than the one in which we’ve found ourselves.

Not surprisingly, the piece has generated a firestorm of speculation about the author’s identity, both online and in the White House itself, which I won’t bother covering here. What interests me are the writer’s reasons for publishing it in the first place. Over the short term, it can only destabilize an already volatile situation, and everyone involved will suffer for it. This implies that the author has a long game in mind, and it had better be pretty compelling. On Twitter, Nate Silver proposed one popular theory: “It seems like the person’s goal is to get outed and secure a very generous advance on a book deal.” He may be right—although if that’s the case, the plan has quickly gone sideways. Reaction on both sides has been far more critical than positive, with Erik Wemple of the Washington Post perhaps putting it best:

Like most anonymous quotes and tracts, this one is a PR stunt. Mr. Senior Administration Official gets to use the distributive power of the New York Times to recast an entire class of federal appointees. No longer are they enablers of a foolish and capricious president. They are now the country’s most precious and valued patriots. In an appearance on Wednesday afternoon, the president pronounced it all a “gutless” exercise. No argument here.

Or as the political blogger Charles P. Pierce says even more savagely in his response on Esquire: “Just shut up and quit.”

But Wemple’s offhand reference to “the distributive power” of the Times makes me think that the real motive is staring us right in the face. It’s a form of Authentication by Newspaper. Let’s say that you’re a senior official in the Trump administration who knows that time is running out. You’re afraid to openly defy the president, but you also want to benefit—or at least to survive—after the ship goes down. In the aftermath, everyone will be scrambling to position themselves for some kind of future career, even though the events of the last few years have left most of them irrevocably tainted. By the time it falls apart, it will be too late to claim that you were gravely concerned. But the solution is a stroke of genius. You plant an anonymous piece in the Times, like the founders of Surety publishing its hash value in the classified ads, except that your platform is vastly more prominent. And you place it there precisely so that you can point to it in the future. After Trump is no longer a threat, you can reveal yourself, with full corroboration from the paper of record, to show that you had the best interests of the country in mind all along. You were one of the good ones. The datestamp is right there. That’s your endgame, no matter how much pain it causes in the meantime. It’s brilliant. But it may not work. As nearly everyone has realized by now, the fact that a “steady state” of conservatives is working to minimize the damage of a Trump presidency to achieve “effective deregulation, historic tax reform, a more robust military and more” is a scandal in itself. This isn’t proof of life. It’s the opposite.

Exile in Dinoville

Earlier this month, a writer named Nick White released Sweet & Low, his debut collection of short fiction. Most of the stories are set in the present day, but one of them, “Break,” includes a paragraph that evokes the early nineties so vividly that I feel obliged to transcribe it here:

For the next few weeks, the three of us spent much of our free time together. We would ride around town listening to Regan’s CDs—she forbid us to play country music in her presence—and we usually ended the night with Forney and me sitting on the hood of his car watching her dance to Liz Phair’s “Never Said”: “All I know is that I’m clean as a whistle, baby,” she sang to us, her voice husky. We went to a lot of movies, and most of the time, I sat between them in a dark theater, our breathing taking the same pattern after a while. We saw Jurassic Park twice at the dollar theater, and I can still remember Forney’s astonishment when the computer-generated brachiosaur filled up the giant screen. “Amazing,” he whispered. “Just amazing.”

And while it may seem like the obvious move to conjure up a period by referring to the popular culture of the time, the juxtaposition of Liz Phair and a brachiosaur sets off its own chain of associations, at least in my own head. Jurassic Park was released on June 11, 1993, and Exile in Guyville came out just eleven days later, and for many young Americans, in the back half of that year, they might as well have been playing simultaneously.

At first, they might not seem to have much to do with each other, apart from their chronological proximity—which can be meaningful in itself. Once enough time has passed, two works of art released back to back can start to seem like siblings, close in age, from the same family. In certain important ways, they’ll have more in common with each other than they ever will with anyone else, and the passage of more than two decades can level even blatant differences in surprising ways. Jurassic Park was a major event long before its release, a big movie from the most successful director of his generation, based on a novel that had already altered the culture. What still feels most vivid about Exile in Guyville, by contrast, is the sense that it was recorded on cassette in total solitude, and that Phair had willed it into existence out of nothing. She was just twenty-six years old, or about the same age as Spielberg when he directed Duel, and the way that their potential was perceived and channeled along divergent lines is illuminating in itself. But now that both the album and the movie feel like our common property, it’s easy to see that both were set apart by a degree of technical facility that was obscured by their extremes of scale. Jurassic Park was so huge that it was hard to appreciate how expertly crafted it was in its details, while Phair’s apparent rawness and the unfinished quality of her tracks distracted from the fact that she was writing pop songs so memorable that I still know all the lyrics after a quarter of a century.

Both also feel like artifacts of a culture that is still coming to terms with its feelings about sex—one by placing it front and center, the other by pushing it so far into the background that a significant plot twist hinges on dinosaurs secretly having babies. But their most meaningful similarity may be that they were followed by a string of what are regarded as underwhelming sequels, although neither one made it easy on their successors. In the case of Jurassic Park, it can be hard to remember the creative breakthrough that it represented. Before its release, I studied the advance images in Entertainment Weekly and reminded myself that the effects couldn’t be that good. When they turned out to be better than I could have imagined, my reaction was much the same as Forney’s in Nick White’s story: “Amazing. Just amazing.” When the movie became a franchise, however, something was lost, including the sense that it was possible for the technology of storytelling to take us by surprise ever again. It wasn’t a story any longer, but a brand. A recent profile by Tyler Coates in Esquire captures much the same moment in Phair’s life:

Looking back, at least for Phair, means recognizing a young woman before she earned indie rock notoriety. “I think what’s most evocative is that lack of self-consciousness,” she said. “It’s the first and last time that I have on record before I had a public awareness of what I represented to other people. There’s me, and then there’s Liz Phair.”

And her subsequent career testifies to the impossible position in which she found herself. A review on All Music describes her sophomore effort, Whip-Smart, as “good enough to retain her critical stature, not good enough to enhance it,” which in itself captures something of the inhuman expectations that critics collectively impose on the artists they claim to love. (The same review observes that “a full five years” separated Exile in Guyville from Whitechocolatespaceegg, as if that were an eternity, even though this seems like a perfectly reasonable span in which to release three ambitious albums.) After two decades, it seems impossible to see Whip-Smart as anything but a really good album that was doomed to be undervalued, and it was about to get even worse. I saw Phair perform live just once, and it wasn’t in the best of surroundings—it was at Field Day in 2003, an event that had been changed at the last minute from an outdoor music festival to a series of opening acts for Radiohead at Giants Stadium. Alone on a huge stage with a guitar, her face projected on a JumboTron, Phair seemed lost, but as game as usual. The tenth anniversary of Exile in Guyville was just around the corner, and a few weeks later, Phair released a self-titled album that was excoriated almost anywhere. Pitchfork gave it zero stars, and it was perceived as a blatant bid for commercial success that called all of her previous work into question. Fifteen years later, it’s very hard to care, and time has done exactly what Phair’s critics never managed to pull off. It confirmed what we should have known all along. Phair broke free, expanded to new territories and crashed through barriers, painfully, maybe even dangerously, and, well, there it is. She found a way.

Bringing the news

“I think there is a tremendous future for a sort of novel that will be called the journalistic novel or perhaps documentary novel, novels of intense social realism based upon the same painstaking reporting that goes into the New Journalism,” the journalist Tom Wolfe wrote in Esquire in 1973. This statement is justifiably famous, and if you think that Wolfe, who passed away yesterday, was making a declaration of intent, you’d be right. In the very next sentence, however, which is quoted much less often, Wolfe added a line that I find tremendously revealing: “I see no reason why novelists who look down on Arthur Hailey’s work couldn’t do the same sort of reporting and research he does—and write it better, if they’re able.” It might seem strange for Wolfe to invoke the author of Hotel and Airport, but two years later, in a long interview with the writer and critic Joe David Bellamy, he doubled down. After Bellamy mentioned Émile Zola as a model for the kind of novel that Wolfe was advocating, the two men had the following exchange:

Wolfe: The fact that [Zola] was bringing you news was a very important thing.

Bellamy: Do you think that’s enough? Isn’t that Arthur Hailey really?

Wolfe: That’s right, it is. The best thing is to have both—to have both someone who will bring you bigger and more exciting chunks of the outside world plus a unique sensibility, or rather a unique way of looking at the world.

I’m surprised that this comparison hasn’t received greater attention, because it gets at something essential about Wolfe’s mixed legacy as a novelist. As an author, Wolfe hovered around the edges of my reading and writing life for decades. In high school, I read The Right Stuff and loved it—it’s hard for me to imagine an easier book to love. After I graduated from college, I landed a job at a financial firm in New York, and the first novel that I checked out from the library that week was The Bonfire of the Vanities. A few years later, I read A Man in Full, and not long ago, when I was thinking seriously about writing a nonfiction book about The Whole Earth Catalog, I read Wolfe’s The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. In each case, I was looking for something more than simple entertainment. I was looking for information, or, in Wolfe’s words, for “news.” It was a cultural position for which Wolfe had consciously prepared himself, as he declared in his famous essay “Stalking the Billion-Footed Beast.” Speaking of the big social novels that had supposedly failed to emerge from the sixties, Wolfe wrote:

That task, as I see it, inevitably involves reporting, which I regard as the most valuable and least understood resource available to any writer with exalted ambitions, whether the medium is print, film, tape, or the stage. Young writers are constantly told, “Write about what you know.” There is nothing wrong with that rule as a starting point, but it seems to get quickly magnified into an unspoken maxim: The only valid experience is personal experience.

As counterexamples, Wolfe cited Dickens, Dostoyevsky, Balzac, Zola, and Lewis as writers who “assumed that the novelist had to go beyond his personal experience and head out into society as a reporter.” But he didn’t mention Arthur Hailey.

Yet when I think back to Wolfe’s novels, I’m left with the uncomfortable sense that when you strip away his unique voice, you’re left with something closer to Hailey or Irving Wallace—with their armfuls of facts, stock characters, and winking nods to real people and events—than to Dickens. That voice was often remarkable, of course, and to speak of removing it, as if it weren’t bound up in the trapezius muscles of the work itself, is inherently ludicrous. But it was also enough to prevent many readers from noticing Wolfe’s very real limits as an imaginative writer. When A Man in Full was greeted by dismissive comments from Norman Mailer, John Irving, and John Updike, who accurately described it as “entertainment,” Wolfe published a response, “My Three Stooges,” in which he boasted about the novel’s glowing reviews and sales figures and humbly opined that the ensuing backlash was like “nothing else…in all the annals of American literature.” He wrote of his critics:

They were shaken. It was as simple as that. A Man in Full was an example—an alarmingly visible one—of a possible, indeed, the likely new direction in late-twentieth and early-twenty-first-century literature: the intensely realistic novel, based upon reporting, that plunges wholeheartedly into the social reality of America today, right now—a revolution in content rather than form—that was about to sweep the arts in America, a revolution that would soon make many prestigious artists, such as our three old novelists, appear effete and irrelevant.

This is grand gossip, even if the entire controversy was swept away a year later by the reception of Jonathan Franzen’s The Corrections, another vast social novel with an accompanying declaration of intent. But it also overlooks the fact that Wolfe’s novels are notably less valuable as reportage than even Updike’s Couples, say, or any of the last three Rabbit books, in which the author diligently left a record of his time, in the form of thousands of closely observed details from the America of the sixties, seventies, and eighties.

And the real irony is that Updike had quietly set himself to the exact task what Wolfe had attempted with much greater fanfare, as Adam Begley notes in his recent biography:

What did [Updike] know about his hero’s new job [in Rabbit is Rich]? What did he know about the business of running a Toyota dealership? As he did for The Coup, he rolled up his sleeves and hit the books. And he also enlisted outside help, hiring a researcher to untangle the arcane protocols of automobile finance and the corporate structure of a dealership—how salesmen are compensated, how many support staff work in the back office, what the salaries are for the various employees, what paperwork is involved in importing foreign cars, and so on. Updike visited showrooms in the Boston area, hunting for tips from salesmen and collecting brochures. He aimed for, and achieved, a level of detail so convincing that the publisher felt obliged to append to a legal boilerplate on the copyright page a specific disclaimer: “No actual Toyota agency in southeastern Pennsylvania is known to the author or in any way depicted herein.”

This is nothing if not reportage, six years before The Bonfire of the Vanities, and not because Updike wanted, in Wolfe’s words, “to cram the world into that novel, all of it,” but in order to tell a story about a specific, utterly ordinary human being. Automobile finance wasn’t as sexy or exotic as Wall Street, which may be why Wolfe failed to acknowledge this. (In Rabbit Redux, instead of writing about the astronauts, Updike wrote about people who seem to barely even notice the moon landing.) Wolfe’s achievements as a journalist are permanent and unquestionable. But we still need the kind of news that the novel can bring, now more than ever, and Wolfe never quite figured out how to do it—even though his gifts were undeniable. Tomorrow, I’ll be taking a closer look at his considerable strengths.

Gore Vidal on literary competition

I went into a line of work in which jealousy is the principal emotion between practitioners. I don’t think I ever suffered from it, because there was no need. But I was aware of it in others, and I found it a regrettable fault.

There was more of a flow to my output of writing in the past, certainly. Having no contemporaries left means you cannot say, “Well, so-and-so will like this,” which you do when you’re younger. You realize there is no so-and-so anymore. You are your own so-and-so. There is a bleak side to it.

—Gore Vidal, to Esquire

Quote of the Day

What I’ve noticed is that people who love what they do, regardless of what that might be, tend to live longer.

—Philip Glass, to Esquire

Quote of the Day

If it gets easy, it becomes less interesting.

—Peter Jackson, to Esquire