Posts Tagged ‘Walter H. Breen’

The Bad Pennies, Part 4

On June 10, 2014, the author Deirdre Saoirse Moen published an email on her blog from Moira Greyland, the daughter of Marion Zimmer Bradley. In a few short paragraphs, Greyland devastatingly described the extent of the abuse that she had suffered at the hand of her mother: “The first time she molested me, I was three. The last time, I was twelve, and able to walk away…I put [her stepfather Walter Breen] in jail for molesting one boy…Walter was a serial rapist with many, many, many victims…but Marion was far, far worse. She was cruel and violent, as well as completely out of her mind sexually. I am not her only victim, nor were her only victims girls.” Later that year, Moira’s brother Mark gave an interview in which he corroborated her claims, while also revealing the difficulty that he had felt in speaking out:

There was always drama and there was always the invisible blade of what would happen if all of this dreadful secret got out. The atmosphere of fear of discovery was simply everywhere and there was no place to hide. Worse, I was ashamed. When you are small you believe stuff, and I felt with my whole heart that I was responsible when she would go bad. There was absolutely no way I was gonna drag the mountain onto my head…And nobody spoke. Everything was always fine and that was my clown suit. I thought everyone knew and that I was such a bad person no one would speak to me. My echo chamber filled me with such fear of exposure I would do anything to make the shadow go away. And I did.

Not surprisingly, these revelations sent a shockwave through the science fiction and fantasy community, with many writers—including those associated with Bradley’s fiction series and magazine—speaking out against what John Scalzi called the “horrific” allegations. Yet while the full extent of Bradley’s abuse may have been unknown, her culpability in Breen’s crimes had been public knowledge for years. In 1998, Bradley testified in a series of depositions about her relationship with her husband, in which she admitted that she was fully aware of his behavior. When asked why she had defended him from accusations of child molestation during the buildup to the World Science Fiction Convention in Berkeley, she responded that she had felt that it was “nobody’s business” but Breen’s. And her involvement went far beyond the decision to keep silent. As the writer Stephin Goldin, whose stepson was abused by Breen, writes in a discussion of the case, which was published shortly after Bradley passed away:

[Bradley] actively aided and abetted her husband, Walter Breen, in the sexual abuse and molestation of children. Before people cast too many tears over her death, they may wish to learn some of the harm she helped perpetrate in the world as well…[Bradley] admits having deliberately covered up her husband’s involvement in activities she knew were illegal and harmful. She took some pains to tell Walter not to molest her own children, but she didn’t care in the least what he did to other children. Readers will be able to judge for themselves the sort of moral character this woman possessed.

And while this information was publicly available for fifteen years before the disclosures by Bradley’s children, they remained largely unknown outside a relatively small circle of fans.

So what happened in the meantime to inspire such a strong response to the statements from Moira and Mark Greyland? I can think of several possible reasons, all of which may have played a role. The first is that our culture has simply changed, which comes close to being a tautology. Another is that the accusations from Bradley’s children are more horrifying, because they indicate that their mother was an abuser as well as an enabler—although this doesn’t explain why her involvement with Breen had gone mostly unremarked until then. The third, which I think gets even closer to the truth, is that the fact that this information was rapidly disseminated online made it harder to ignore. (As Charles Morgan and Hubert Walker write in an article in CoinWeek: “Consider this: as a hobby and an industry, we’re actually quite fortunate that the Breen scandal erupted when it did. Had Breen’s crimes come to light in the Internet Age, the hobby as a whole could have been implicated.” And you could say much the same of the science fiction community.) A fourth explanation is that it can be difficult for us to collectively catch up with allegations that have existed for a long time, until they’ve been catalyzed by a fresh piece of news. As the events of the last two years have made clear, there’s a huge backlog of horrific behavior on the part of our artistic and literary heroes that we haven’t yet processed, in large part because we’ve been preoccupied with developments in the present. I’ve made this point before about Saul Bellow, among others, but an even more relevant example is the Nobel laureate André Gide, whose abuse of young boys was remarkably similar to Breen’s. A lot of this information is out there, but it’s been grandfathered into the conversation, and we don’t always pay attention to it until we don’t have a choice.

But there’s one more factor that may be the most significant of all, and it brings us full circle to Breen’s mentor. William Herbert Sheldon’s crimes were of a different kind, but he benefited from the existence of subcultures that allowed him to operate for years without scrutiny. The Ivy League nude posture photo scandal, as its name implies, depended on the existence of a relatively closed world that permitted Sheldon’s work to continue. I suspect that much the same holds true of the community of numismatists, who trusted him with access to rare coins that he quietly switched out for his own inferior samples, mostly because he could. And it’s worth noting that these were groups of people who presumably thought of themselves as more intelligent than average, which might actually allow such behavior to go unchallenged for longer. Breen, who became involved with Sheldon through their shared interest in both coins and gifted children, could hardly have failed to notice this. (While writing this post, incidentally, I became aware of the novel Wild Talent by Wilson Tucker, first published in 1954, about a telepath named Breen who is conscripted to work for the government. The main character is undoubtedly named after Walter Breen—Tucker named characters after prominent fans so often that it inspired its own term of art. And the timing, which seems too perfect to be just a coincidence, makes me wonder if there might be something to Jack Sarfatti’s claims about Breen and Sheldon’s work on psychic powers with children in the early fifties.) Science fiction, of course, is another such subculture. Or at least it used to be. Nowadays, it’s embedded in the mainstream, which makes it harder for predators to work undetected, or for their crimes to be covered up for long. Bad pennies, as we’ve all seen, can appear in any context. And the best way to deal with them may be to let the truth circulate as widely as possible.

The Bad Pennies, Part 3

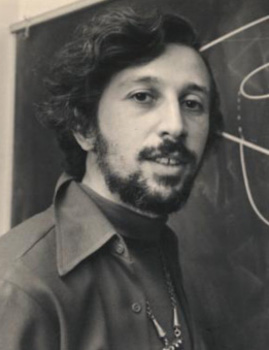

On September 4, 1964, the annual World Science Fiction Convention opened its doors at the Hotel Leamington in Oakland, California. The guests of honor included Leigh Brackett, Edmond Hamilton, and Forrest Ackerman, with Anthony Boucher serving as toastmaster, but the conversation that weekend was dominated by a fan who wasn’t there. After a heated debate, Walter H. Breen had been banned from attendance by the convention committee, for reasons that were outlined by Bill Donaho in a special fanzine issue titled “The Great Breen Boondoggle, or All Berkeley Is Plunged into War.” (The newsletter was privately circulated, and Donaho asked that it not be quoted, but the complete text can be found online.) As Donaho makes abundantly clear, it was common knowledge among local fans that Breen—who had moved to Berkeley in the fifties—was a serial abuser of children. Four cases are described in detail, with allusions to numerous others. I won’t quote them here, but they’re horrifying, both in themselves and in the length of time over which they took place. Donaho writes:

Walter’s recent behavior has been getting many Berkeley parents not just alarmed, but semi-hysterical. If Walter is in the same room with a young boy, he never takes his eyes off the kid. He’ll be semi-abstractedly talking to someone else, but his eyes will be on the boy. And if the kid goes to the bathroom, Walter gets up and follows him in…Knowing Walter I can readily believe that he was completely oblivious to the obvious signs of strong objection. Those who say Walter is a child are right and as a child he is completely oblivious to other people’s desires and wishes unless hit on the head with them.

In the meantime, the prominent fan Alva Rogers said that he felt “great reluctance” to exclude anyone from the community, and he had a novel solution to ensure the safety of his own children whenever Breen came to visit: “He wanted to protect his kids of course, but that the situation was adequately handled at his house by having them barricade themselves in their room.”

But the most unbelievable aspect of the entire story is that no one involved seems to have disputed the facts themselves. What remained a source of controversy—both before the convention and long afterward—was the appropriate action to take, if any, against Breen. As Donaho writes of the reactions of two influential fans, with the name of a child redacted:

They swung between two points of view. “We must protect T—” and “We’re all kooks. Walter is just a little kookier than the rest of us. Where will it all end if we start rejecting people because they’re kooky?” So they swung from on the one hand proposing that if Walter wasn’t to be expelled, then the banning from individual homes should be extended so that club meetings were only held in such homes, and on the other hand calling the whole series of discussions “McCarthyite” and “Star Chamber.” “I don’t want Walter around T—, but if we do such a horrible thing as expelling him, I’ll quit fandom.”

On a more practical level, some of the organizers were concerned that if they banned Breen, they would also lose Marion Zimmer Bradley, who married him shortly before the convention began. When informed of the controversy, Breen explicitly threatened to keep Bradley away, which led to much consternation. Donaho explains: “Many of us like Marion and all this is not a very pleasant welcome to Berkeley for her. Not to mention the fact that it’s going to severely strain her relations with almost all Berkeley fans, since naturally she will defend Walter…We feel that she most probably at least knows about some of Walter’s affairs with adolescent males but believes in tolerance.”

Even after the decision was made, the wounds remained raw, and many writers and fans seemed to frame the entire incident primarily in terms of its impact on the community. In the second volume of his biography In Dialogue With His Century, William H. Patterson quotes a letter that Heinlein sent to Marion Zimmer Bradley on July 15, 1965:

The fan nuisance we were subjected to was nothing like as nasty as the horrible things that were done to you two but it was bad enough that we could get nothing else done during the weeks it went on and utterly spoiled what should have been a pleasant, happy winter. But it resulted in a decision which has made our life much pleasanter already…We have cut off all contact with organized fandom. I regret that we will miss meeting some worthwhile people in the future as the result of this decision. But the percentage of poisonous jerks in the ranks of fans makes the price too high; we’ll find our friends elsewhere.

Patterson, typically, doesn’t scrutinize this statement, moving on immediately to an unrelated story about Jerry Pournelle with the transition: “Fortunately, not all their fan interactions were were so unpleasant.” His only discussion of the incident takes the form of a footnote in which he quotes “a good short discussion” of the Breendoggle from a glossary of fan terms: “The sole point fans on both sides can agree upon is that the resulting feud had long-lasting effects [and] tore the fabric of the microcosm beyond repair…The opposing forces retired to lick their wounds and assure themselves that they had been undeniably right while the other side had been unmistakably wrong.”

By now, I hope that we can arrive at another “single point” of agreement, which is that fandom, in its effort to see itself as a place of inclusiveness for the “kooks,” disastrously failed to protect Breen’s victims. In 1991, Breen was charged with eight felony counts of child molestation and sentenced to ten years in prison—which led in turn to a comparable moment of reckoning in another subculture in which he had played an even more prominent role. Breen was renowned among coin collectors as the author of such reference works as the Complete Encyclopedia of U.S. and Colonial Coins, and the reaction within the world of numismatics was strikingly similar to what had taken place a quarter of a century earlier in Berkeley. As Charles Morgan and Hubert Walker write in an excellent article in CoinWeek:

Even in 1991, with the seeming finality of a confession and a ten-year prison sentence, it was like the sci-fi dustups of the 1960s all over again. This time, however, it was coin collectors and fans of Breen’s numismatic work that came to his defense. One such defender was fellow author John D. Wright, who wrote a letter to Coin World that stated: “My friend Walter Breen has confessed to a sin, and for this, other friends of mine have picked up stones to throw at him.” Wright criticized the American Numismatic Association for revoking Breen’s membership mere weeks after awarding him the Heath Literary Award, saying that while he did not condone Breen’s “lewd and lascivious acts,” he did not see the charge, Breen’s guilty plea or subsequent conviction as “reason for expulsion from the ANA or from any other numismatic organization.”

It’s enough to make you wonder if anything has changed in the last fifty years—but I think that it has. And the best example is the response to a more recent series of revelations about the role of Marion Zimmer Bradley. I’ll dive into this in greater detail tomorrow, in what I hope will be my final post on the subject.

The Bad Pennies, Part 2

William Herbert Sheldon achieved his greatest fame by classifying human beings into degrees of three basic categories—ectomorph, endomorph, and mesomorph—based on their physical proportions. At exactly the same time, and with far more enduring results, he did something similar for rare coins. In 1949, he developed what became known as the Sheldon coin grading scale, a modified version of which is used to this day by numismatists and coin collectors. In his book Early American Cents, Sheldon notes that numismatists gain much of their knowledge from studying photographs of coins, and he continues:

A workable idea can be formed as to how the various shades of condition from a poor coin to a perfect coin can be scaled or graded. This progression is of course a continuum, not a series of discrete steps, and for those who think quantitatively rather than adjectivally it is more accurate to grade coins on a numerical scale than to try to fit them into a series of adjectival pigeonholes.

Sheldon goes on to provide “a quantitative scale of condition” for the coins known as large cents, ranging from 1 to 70, with the highest rating reserved for specimens in an uncirculated state. And while I don’t know enough about Sheldon to speculate on the direction of influence, the entire project was strikingly similar to his work on somatotypes, which classified individuals on a quantitative scale, ranging from 1 to 7, based on the close examination of photos.

Both aspects of Sheldon’s career were also tainted by what appears to have been a deep streak of dishonesty. One of his former assistants, Barbara Honeyman Heath, said decades later that Sheldon had “mutilated and manipulated the materials” for his book Atlas of Men, and an even stranger scandal emerged after his death. In the course of his research on large cents, Sheldon frequently studied the examples held by the American Numismatic Society in New York, including a collection donated by the numismatist George H. Clapp. As a legal filing states:

ANS took physical possession of the Clapp collection in 1947. At some time after ANS’s receipt of the Clapp collection and before 1973, a number of coins were surreptitiously stolen from the Clapp collection by someone who replaced the Clapp coins with coins of the same variety but of inferior grade…The late William Sheldon, a preeminent classifier, cataloguer, and collector of large cents, lived near the ANS until 1973. During that time, Sheldon spent much time at ANS, unguarded, examining the Clapp collection. In 1973-1974, the ANS catalogued its Clapp collection and discovered that some of the coins had been switched for inferior coins of the same variety.

In 1991, a collector published a book, United States Large Cents, that included photos of coins that had been acquired from Sheldon. After closer scrutiny, they were identified as the coins that had been stolen from the Clapp collection—and Sheldon also appears to have pilfered coins from at least four other private collectors, switching them out in each case with inferior examples of his own.

Sheldon’s thefts evidently took place during his research for Early American Cents and its successor, which was titled Penny Whimsy. The revised edition was prepared by Sheldon in collaboration with Walter H. Breen, a much younger numismatist whom he had met while teaching at Columbia University. The two men worked together on what become known as the Sheldon-Breen rarity scale, which rates a coin’s scarcity on a scale from 1 to 9. And much as in Sheldon’s case, Breen’s interest in coins was mirrored in his fascination with unusual human beings, particularly those of high intelligence. Breen was an early member of Mensa, and he evidently attempted to start a program for gifted children that may have involved Sheldon. Our primary source here is Jack Sarfatti, a controversial physicist with ties to Uri Geller, who has made some unusual claims about this project:

I was part of a group of super kids, these genius kids that were being studied at the Columbia University Laboratory of William Sheldon, and one of his assistants, a Walter Breen—we’re talking like 1953…It was also connected to the government. It had something to do with what later became Sandia Labs in New Mexico…There were experiments, and they would just sit with the kids, you know, trying to get them to move objects. We never moved anything, but there was a whole program going on about this. Also, they talked about aliens and flying saucers, trying to figure out how they fly, and all that kind of stuff, it was a lot of science fiction.

In the same interview, Sarfatti claimed that Alan Greenspan had been involved, and that “it was all connected somehow with Ayn Rand,” which is more plausible than it sounds. Sarfatti also stated that Breen often took the kids to science fiction conventions, and he added: “Oh, and I met Isaac Asimov at that time.”

Whether or not we take this seriously, it’s obvious that Breen was interested in fringe aspects of psychology, often with a paranormal or mystical element, which he later called “biological humanics.” (Breen said in an interview that he investigated various subcultures as a sociologist, “including not only the Beat Generation groups on both coasts but also some of the very earliest hippies, finding out incidentally that some ideas that the bunch of us had developed in science fiction fandom had gotten into the hippie subculture and were being paraded around as their own inventions.” He also said that he had broken away from Sheldon after becoming concerned by his antisemitism.) And another side of his work wouldn’t become widely known for some time. In the critical anthology Before Stonewall, the scholar Donald Mader writes:

Walter Henry Breen (also known under his pseudonym J.Z. Eglinton) was the most important theorist of man-boy love to appear since the German figures…in the first third of the twentieth century…Breen independently affirmed, as they had, the distinction between what he termed “Greek love” (pederasty, or intergenerational homosexual relationships) and “androphile homosexuality” (eroticism between adult males)…He himself argued that androphile homosexuality had usurped the “true” tradition of homosexuality which belonged to Greek love.

Writing as Eglinton, Breen published a book on the subject, Greek Love, which he dedicated to his wife Marion Zimmer Bradley, who became famous decades later as the author of The Mists of Avalon—and it eventually became clear that both Breen and Bradley were guilty of offenses that far outweighed Sheldon’s thievery and deception. I’ll talk more about this in a concluding post tomorrow.

The Bad Pennies, Part 1

For the last couple of months, I’ve been trying to pull together the tangled ends of a story that seems so complicated—and which encompasses so many unlikely personalities—that I doubt that I’ll ever get to the bottom of it, at least not without devoting more time to the project than I currently have to spare. (It really requires a good biography, and maybe two, and in the meantime, I’m just going to throw out a few leads in the hopes that somebody else will follow up.) It centers on a man named William Herbert Sheldon, who was born in 1898 and died in 1977. Sheldon was a psychologist and numismatist who received his doctorate from the University of Chicago and studied under Carl Jung. He’s best known today for his theory of somatotypes, which classified all human beings into degrees of endomorph, mesomorph, or ectomorph, based on their physical proportions. Sheldon argued that an individual’s build was an indication of character and ability, as Ron Rosenbaum wrote over twenty years ago in a fascinating investigative piece for the New York Times:

[Sheldon] believed that every individual harbored within him different degrees of each of the three character components. By using body measurements and ratios derived from nude photographs, Sheldon believed he could assign every individual a three-digit number representing the three components, components that Sheldon believed were inborn—genetic—and remained unwavering determinants of character regardless of transitory weight change. In other words, physique equals destiny.

Sheldon’s work carried obvious overtones of eugenics, even racism, which must have been evident to many observers even at the time. (In the early twenties, Sheldon wrote a paper titled “The Intelligence of Mexican Children,” in which he asserted that “Negro intelligence” comes to a “standstill at about the tenth year.”) And these themes became even more explicit in the writings of his closest collaborator, the anthropologist Earnest A. Hooton. In the fifties, Hooton’s “research” on the physical attributes that were allegedly associated with criminality was treated with guarded respect even by the likes of Martin Gardner, who wrote in his book Fads and Fallacies:

The theory that criminals have characteristic “stigmata”—facial and bodily features which distinguish them from other men—was…revived by Professor Earnest A. Hooton, of the Harvard anthropology faculty. In a study made in the thirties, Dr. Hooton found all kinds of body correlations with certain types of criminality. For example, robbers tend to have heavy beards, diffused pigment in the iris, attached ear lobes, and six other body traits. Hooton must not be regarded as a crank, however—his work is too carefully done to fall into that category—but his conclusions have not been accepted by most of his colleagues, who think his research lacked adequate controls.

Gardner should have known better. Hooton, like Sheldon, was obsessed with dividing up human beings on the basis of their morphological characteristics, as he wrote in the Times in 1936: “Our real purpose should be to segregate and eliminate the unfit, worthless, degenerate and anti-social portion of each racial and ethnic strain in our population, so that we may utilize the substantial merits of the sound majority, and the special and diversified gifts of its superior members.”

Sheldon and Hooton’s work reached its culmination, or nadir, in one of the strangest episodes in the history of anthropology, which Rosenbaum’s article memorably calls “The Great Ivy League Nude Posture Photo Scandal.” For decades, such institutions as Harvard College had photographed incoming freshmen in the nude, supposedly to look for signs of scoliosis and rickets. Sheldon and Hooton took advantage of these existing programs to take nude photos of students, both male and female, at colleges including Harvard, Radcliffe, Princeton, Yale, Wellesley, and Vassar, ostensibly to study posture, but really to gather raw data for their work on somatotypes. The project went on for decades, and Rosenbaum points out that the number of famous alumni who had their pictures taken staggers the imagination: “George Bush, George Pataki, Brandon Tartikoff and Bob Woodward were required to do it at Yale. At Vassar, Meryl Streep; at Mount Holyoke, Wendy Wasserstein; at Wellesley, Hillary Rodham and Diane Sawyer.” After some diligent sleuthing, Rosenbaum determined that most of these photographs were later destroyed, but a collection of negatives survived at the National Anthropological Archives in the Smithsonian, where he was ultimately allowed to view some of them. He writes of the experience:

As I thumbed rapidly through box after box to confirm that the entries described in the Finder’s Aid were actually there, I tried to glance at only the faces. It was a decision that paid off, because it was in them that a crucial difference between the men and the women revealed itself. For the most part, the men looked diffident, oblivious. That’s not surprising considering that men of that era were accustomed to undressing for draft physicals and athletic-squad weigh-ins. But the faces of the women were another story. I was surprised at how many looked deeply unhappy, as if pained at being subjected to this procedure. On the faces of quite a few I saw what looked like grimaces, reflecting pronounced discomfort, perhaps even anger.

And it’s clearly the women who bore the greatest degree of lingering humiliation and fear. Rumors circulated for years that the pictures had been stolen and sold, and such notable figures as Nora Ephron, Sally Quinn, and Judith Martin speak candidly to Rosenbaum of how they were haunted by these memories. (Quinn tells him: “You always thought when you did it that one day they’d come back to haunt you. That twenty-five years later, when your husband was running for president, they’d show up in Penthouse.” For the record, according to Rosenbaum, when the future Hillary Clinton attended Wellesley, undergraduates were allowed to take the pictures “only partly nude.”) Rosenbaum captures the unsavory nature of the entire program in terms that might have been published yesterday:

Suddenly the subjects of Sheldon’s photography leaped into the foreground: the shy girl, the fat girl, the religiously conservative, the victim of inappropriate parental attention…In a culture that already encourages women to scrutinize their bodies critically, the first thing that happens to these women when they arrive at college is an intrusive, uncomfortable, public examination of their nude bodies.

If William Herbert Sheldon’s story had ended there, it would be strange enough, but there’s a lot more to be told. I haven’t even mentioned his work as a numismatist, which led to a stolen penny scandal that rocked the world of coin collecting as deeply as the nude photos did the Ivy League. But the real reason I wanted to talk about him involves one of his protégés, whom Sheldon met while teaching in the fifties at Columbia. His name was Walter H. Breen, who later married the fantasy author Marion Zimmer Bradley—which leads us in turn to one of the darkest episodes in the entire history of science fiction. I’ll be talking more about this tomorrow.

Under the dome

In the early seventies, a boy named Jaron Lanier was living with his father in a tent near Las Cruces, New Mexico. Decades later, Lanier would achieve worldwide acclaim as one of the founders of virtual reality—his company was the first to sell VR headsets and gloves—but at the time, he was ten years old and recovering from a succession of domestic tragedies. When he was nine, his mother Lilly had been killed in a horrific car accident; he was hospitalized for nearly a year with a series of infections; and his family’s new home burned down the day after construction was completed. Lanier’s father, Ellery, barely managed to scrape together enough money to buy an acre of undeveloped land in the desert, where they lived in tents for two years. (Ellery Lanier was a fascinating figure in his own right, and I hope one day to take a more detailed look at his career. He was a peripheral member of a circle of science fiction writers that included Lester del Rey and the radio host Long John Nebel, and he wrote nonfiction articles in the fifties for Fantastic and Amazing. As a younger man, he had known Gurdjieff and Aldous Huxley, and he was close friends with William Herbert Sheldon, the controversial psychologist best known for coining the terms “ectomorph,” “mesomorph,” and “endomorph,” as well as for his involvement with the Ivy League nude posture photos. Sheldon, in turn, was a numismatist who mentored Walter H. Breen, the husband of Marion Zimmer Bradley, about whom the less said the better. There’s obviously a lot to unpack here, but this post isn’t about that.)

When Lanier was about twelve years old, his father proposed that he design and build a house in which the two of them could live. In his memoir Dawn of the New Everything, Lanier speculates that this was his father’s way of helping him to deal with his recent traumas: “He realized that I needed a meaty obsession if I was ever going to become fully functional again.” At the time, Lanier was fascinated by the work of Hieronymus Bosch, especially The Garden of Earthly Delights, and he was equally intrigued when his father gave him a book titled Plants as Inventors. He decided that they should build a house with elements based on botanical structures, which may have been his father’s plan all along. Lanier remembers:

Ellery said he thought I might enjoy another book, in that case. This turned out to be a roughly designed publication in the form of an extra-thick magazine called Domebook. It was an offshoot of Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth Catalog. Buckminster Fuller had been promoting geodesic domes as ideal structures, and they embodied the techie utopian spirit of the times.

At first, Lanier actually thought that a dome would be too mainstream: “I don’t want our house to be like any other house, and other people are building geodesic domes.” His father replied that it would probably be easier to get a construction permit if they included “this countercultural cliché,” and Lanier ultimately granted the point.

The project lasted for seven years. In the classic Fuller fashion, Lanier began with models made of drinking straws, using the tables from the Domebook to calculate the angles. He recalls:

My design strategy was to mix “conventional” geodesic domes with connecting elements that would be profoundly weird and irregular. There was to be one big dome, about fifty feet across, and a medium-size one, to be connected by a strange passage, which would serve as the kitchen, formed out of two tilted, intersecting nine-sided pyramids…The overall form reminded me a little of the Starship Enterprise—which has two engines connected to a main body and a prominent disc jutting out in front—if you filled out the discs and cylinders of that design into spheres…At any rate it was a form that I liked and that Ellery accepted. There were a few passes back and forth with the building permit people, and ultimately Ellery did have to intervene to argue the case, but we got a permit.

Amazingly enough, it all sort of held together. Like many dome builders, Lanier ran into multiple problems on the construction side, in part because of the unreliable advice of the Domebook, which “pretended to offer solutions when it was actually reporting on ongoing experiments.” A decade later, when Lanier met Stewart Brand for the first time, he volunteered the fact that he had grown up in a dome. Brand asked immediately: “Did it leak?” Lanier replied: “Of course it leaked!”

Yet the really remarkable thing was that it worked at all. Fuller’s architectural ideas may have been flawed in practice, but they became popular in the counterculture for many of the same reasons that later led to the founding of the Homebrew Computer Club. Like a kid learning how to code, with the aid of a few simple formulas, diagrams, and rules of thumb, a teenager could build a house that looked like the Enterprise. It was a hackable approach that encouraged experimentation, and the simplicity of the structural principles involved—you could squeeze them into a couple of pages—allowed the information to be freely distributed, much like today’s online blueprints for printable houses. And Lanier adored the result:

The larger dome was big enough that you could almost focus at infinity while staring up at the curve of the baggy silver ceiling…We called it “the dome,” or “Earth Station Lanier.” One would “go dome” instead of going home…There wasn’t a proper bathroom or kitchen. Instead, tubs, sinks, and showers were inserted into the structure according to how the plumbing could be routed though the bizarre shapes I had chosen. A sink was unusually high off the ground; you needed a stepping stool to use it. Conventional choices regarding privacy, sleep schedules, or studying were not really possible. I loved the place; dreamt about it while sleeping inside it.

His father stayed there for another thirty years. Even after Lanier moved away, he never entirely got over it, and he lives today with his family in a house with an attached structure much like the one he left behind in New Mexico. As he concludes: “We live back in the dome, more or less.”

I’ll be appearing tonight at the Deep Dish reading series at Volumes Bookcafe in Chicago at 7pm, along with Cory Doctorow and an exciting group of speculative fiction writers. Hope to see some of you there!