Posts Tagged ‘Pixar’

Inside the sweatbox

Yesterday, I watched a remarkable documentary called The Sweatbox, which belongs on the short list of films—along with Hearts of Darkness and the special features for The Lord of the Rings—that I would recommend to anyone who ever thought that it might be fun to work in the movies. It was never officially released, but a copy occasionally surfaces on YouTube, and I strongly suggest watching the version available now before it disappears yet again. For the first thirty minutes or so, it plays like a standard featurette of the sort that you might have found on the second disc of a home video release from two decades ago, which is exactly what it was supposed to be. Its protagonist, improbably, is Sting, who was approached by Disney in the late nineties to compose six songs for a movie titled Kingdom of the Sun. (One of the two directors of the documentary is Sting’s wife, Trudie Styler, a producer whose other credits include Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels and Moon.) The feature was conceived by animator Roger Allers, who was just coming off the enormous success of The Lion King, as a mixture of Peruvian mythology, drama, mysticism, and comedy, with a central plot lifted from The Prince and the Pauper. After two years of production, the work in progress was screened for the first time for studio executives. As always, the atmosphere was tense, but no more than usual, and it inspired the standard amount of black humor from the creative team. As one artist jokes nervously before the screening: “You don’t want them to come in and go, ‘Oh, you know what, we don’t like that idea of the one guy looking like the other guy. Let’s get rid of the basis of the movie.’ This would be a good time for them to tell us.”

Of course, that’s exactly what happened. The top brass at Disney hated the movie, production was halted, and Allers left the project that was ultimately retooled into The Emperor’s New Groove, which reused much of the design work and finished animation while tossing out entire characters—along with most of Sting’s songs—and introducing new ones. It’s a story that has fascinated me ever since I first heard about it, around the time of the movie’s initial release, and I’m excited beyond words that The Sweatbox even exists. (The title of the documentary, which was later edited down to an innocuous special feature for the DVD, refers to the room at the studio in Burbank in which rough work is screened.) And while the events that it depicts are extraordinary, they represent only an extreme case of the customary process at Disney and Pixar, at least if you believe the ways in which that the studio likes to talk about itself. In a profile that ran a while back in The New Yorker, the director Andrew Stanton expressed it in terms that I’ve never forgotten:

“We spent two years with Eve getting shot in her heart battery, and Wall-E giving her his battery, and it never worked. Finally—finally—we realized he should lose his memory instead, and thus his personality…We’re in this weird, hermetically sealed freakazoid place where everybody’s trying their best to do their best—and the films still suck for three out of the four years it takes to make them.

This statement appeared in print six months before the release of Stanton’s live action debut John Carter, which implies that this method is far from infallible. And the drama behind The Emperor’s New Groove was unprecedented even by the studio’s relentless standards. As executive Thomas Schumacher says at one point: “We always say, Oh, this is normal. [But] we’ve never been through this before.”

As it happens, I watched The Sweatbox shortly after reading an autobiographical essay by the artist Cassandra Smolcic about her experiences in the “weird, hermetically sealed freakazoid” environment of Pixar. It’s a long read, but riveting throughout, and it makes it clear that the issues at the studio went far beyond the actions of John Lasseter. And while I could focus on any number of details or anecdotes, I’d like to highlight one section, about the firing of director Brenda Chapman halfway through the production of Brave:

Curious about the downfall of such an accomplished, groundbreaking woman, I began taking the company pulse soon after Brenda’s firing had been announced. To the general population of the studio — many of whom had never worked on Brave because it was not yet in full-steam production — it seemed as though Brenda’s firing was considered justifiable. Rumor had it that she had been indecisive, unconfident and ineffective as a director. But for me and others who worked closely with the second-time director, there was a palpable sense of outrage, disbelief and mourning after Brenda was removed from the film. One artist, who’d been on the Brave story team for years, passionately told me how she didn’t find Brenda to be indecisive at all. Brenda knew exactly what film she was making and was very clear in communicating her vision, the story artist said, and the film she was making was powerful and compelling. “From where I was sitting, the only problem with Brenda and her version of Brave was that it was a story told about a mother and a daughter from a distinctly female lens,” she explained.

Smolcic adds: “During the summer of 2009, I personally worked on Brave while Brenda was still in charge. I likewise never felt that she was uncertain about the kind of film she was making, or how to go about making it.”

There are obvious parallels between what happened to Allers and to Chapman, which might seem to undercut the notion that the latter’s firing had anything to do with the fact that she was a woman. But there are a few other points worth raising. One is that no one seems to have applied the words “indecisive, unconfident, and ineffective” to Allers, who voluntarily left the production after his request to push back the release date was denied. And if The Sweatbox is any indication, the situation of women and other historically underrepresented groups at Disney during this period was just as bad as it was at Pixar—I counted exactly one woman who speaks onscreen, for less than fifteen seconds, and all the other faces that we see are white and male. (After Sting expresses concern about the original ending of The Emperor’s New Groove, in which the rain forest is cut down to build an amusement park, an avuncular Roy Disney confides to the camera: “We’re gonna offend somebody sooner or later. I mean, it’s impossible to do anything in the world these days without offending somebody.” Which betrays a certain nostalgia for a time when no one, apparently, was offended by anything that the studio might do.) One of the major players in the documentary is Thomas Schumacher, the head of Disney Animation, who has since been accused of “explicit sexual language and harassment in the workplace,” according to a report in the Wall Street Journal. In the footage that we see, Schumacher and fellow executive Peter Schneider don’t come off particularly well, which may just be a consequence of the perspective from which the story is told. But it’s equally clear that the mythical process that allows such movies to “suck” for three out of four years is only practicable for filmmakers who look and sound like their counterparts on the other side of the sweatbox, which grants them the necessary creative freedom to try and fail repeatedly—a luxury that women are rarely granted. What happened to Allers on Kingdom of the Sun is still astounding. But it might be even more noteworthy that he survived for as long as he did.

The secret villain

Note: This post alludes to a plot point from Pixar’s Coco.

A few years ago, after Frozen was first released, The Atlantic ran an essay by Gina Dalfonzo complaining about the moment—fair warning for a spoiler—when Prince Hans was revealed to be the film’s true villain. Dalfonzo wrote:

That moment would have wrecked me if I’d seen it as a child, and the makers of Frozen couldn’t have picked a more surefire way to unsettle its young audience members…There is something uniquely horrifying about finding out that a person—even a fictional person—who’s won you over is, in fact, rotten to the core. And it’s that much more traumatizing when you’re six or seven years old. Children will, in their lifetimes, necessarily learn that not everyone who looks or seems trustworthy is trustworthy—but Frozen’s big twist is a needlessly upsetting way to teach that lesson.

Whatever you might think of her argument, it’s obvious that Disney didn’t buy it. In fact, the twist in question—in which a seemingly innocuous supporting character is exposed in the third act as the real bad guy—has appeared so monotonously in the studio’s recent movies that I was already complaining about it a year and a half ago. By my count, the films that fall back on his convention include not just Frozen, but Wreck-It Ralph, Zootopia, and now the excellent Coco, which implies that the formula is spilling over from its parent studio to Pixar. (To be fair, it goes at least as far back as Toy Story 2, but it didn’t become the equivalent of the house style until about six or seven years ago.)

This might seem like a small point of storytelling, but it interests me, both because we’ve been seeing it so often and because it’s very different from the stock Disney approach of the past, in which the lines between good and evil were clearly demarcated from the opening frame. In some ways, it’s a positive development—among other things, it means that characters are no longer defined primarily by their appearance—and it may just be a natural instance of a studio returning repeatedly to a trick that has worked in the past. But I can’t resist a more sinister reading. All of the examples that I’ve cited come from the period since John Lasseter took over as the chief creative officer of Disney Animation Studios, and as we’ve recently learned, he wasn’t entirely what he seemed, either. A Variety article recounts:

For more than twenty years, young women at Pixar Animation Studios have been warned about the behavior of John Lasseter, who just disclosed that he is taking a leave due to inappropriate conduct with women. The company’s cofounder is known as a hugger. Around Pixar’s Emeryville, California, offices, a hug from Lasseter is seen as a mark of approval. But among female employees, there has long been widespread discomfort about Lasseter’s hugs and about the other ways he showers attention on young women…“Just be warned, he likes to hug the pretty girls,” [a former employee] said she was told. “He might try to kiss you on the mouth.” The employee said she was alarmed by how routine the whole thing seemed. “There was kind of a big cult around John,” she says.

And a piece in The Hollywood Reporter adds: “Sources say some women at Pixar knew to turn their heads quickly when encountering him to avoid his kisses. Some used a move they called ‘the Lasseter’ to prevent their boss from putting his hands on their legs.”

Of all the horror stories that have emerged lately about sexual harassment by men in power, this is one of the hardest for me to read, and it raises troubling questions about the culture of a company that I’ve admired for a long time. (Among other things, it sheds a new light on the Pixar motto, as expressed by Andrew Stanton, that I’ve quoted here before: “We’re in this weird, hermetically sealed freakazoid place where everybody’s trying their best to do their best—and the films still suck for three out of the four years it takes to make them.” But it also goes without saying that it’s far easier to fail repeatedly on your way to success if you’re a white male who fits a certain profile. And these larger cultural issues evidently contributed to the departure from the studio of Rashida Jones and her writing partner.) It also makes me wonder a little about the movies themselves. After the news broke about Lasseter, there were comments online about his resemblance to Lotso in Toy Story 3, who announces jovially: “First thing you gotta know about me—I’m a hugger!” But the more I think about it, the more this seems like a bona fide inside joke about a situation that must have been widely acknowledged. As a recent article in Deadline reveals:

[Lasseter] attended some wrap parties with a handler to ensure he would not engage in inappropriate conduct with women, say two people with direct knowledge of the situation…Two sources recounted Lasseter’s obsession with the young character actresses portraying Disney’s Fairies, a product line built around the character of Tinker Bell. At the animator’s insistence, Disney flew the women to a New York event. One Pixar employee became the designated escort as Lasseter took the young women out drinking one night, and to a party the following evening. “He was inappropriate with the fairies,” said the former Pixar executive, referring to physical contact that included long hugs. “We had to have someone make sure he wasn’t alone with them.”

Whether or not the reference in Toy Story 3 was deliberate—the script is credited to Michael Arndt, based on a story by Lasseter, Stanton, and Lee Unkrich, and presumably with contributions from many other hands—it must have inspired a few uneasy smiles of recognition at Pixar. And its emphasis on seemingly benign figures who reveal an unexpected dark side, including Lotso himself, can easily be read as an expression, conscious or otherwise, of the tensions between Lasseter’s public image and his long history of misbehavior. (I’ve been thinking along similar lines about Kevin Spacey, whose “sheer meretriciousness” I identified a long time ago as one of his most appealing qualities as an actor, and of whom I once wrote here: “Spacey always seems to be impersonating someone else, and he does the best impersonation of a great actor that I’ve ever seen.” And it seems now that this calculated form of pretending amounted to a way of life.) Lasseter’s influence over Pixar and Disney is so profound that it doesn’t seem farfetched to see its films both as an expression of his internal divisions and of the reactions of those around him, and you don’t need to look far for parallel examples. My daughter, as it happens, knows exactly who Lasseter is—he’s the big guy in the Hawaiian shirt who appears at the beginning of all of her Hayao Miyazaki movies, talking about how much he loves the film that we’re about to see. I don’t doubt that he does. But not only do Miyazaki’s greatest films lack villains entirely, but the twist generally runs in the opposite direction, in which a character who initially seems forbidding or frightening is revealed to be kinder than you think. Simply on the level of storytelling, I know which version I prefer. Under Lasseter, Disney and Pixar have produced some of the best films of recent decades, but they also have their limits. And it only stands to reason that these limitations might have something to do with the man who was more responsible than anyone else for bringing these movies to life.

Moana and the two studios

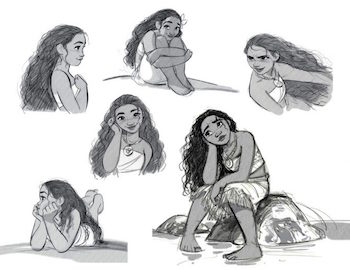

If the history of animation had a portentous opening voiceover, it would probably say: “In the beginning was the storyboard.” The earliest animated cartoons were short and silent, so it made sense to plan them out as a series of rough thumbnail sketches. Even after they added sound and dialogue and became longer in length, the practice survived, which is why so many of the classic Disney movies are so episodic. They weren’t plotted on paper from beginning to end, but conceived as a sequence of set pieces, often with separate teams, and they were planned by artists who thought primarily with a pencil. This approach generated extraordinary visual achievements, but it could also result in movies, like Alice in Wonderland, that were brilliant in their individual components but failed to build to anything more. Later, in the eighties, Disney switched over to a production cycle that was closer to that of a live-action feature, with a traditional screenplay serving as the basis for future development. This led to more coherent stories, and it’s hard to imagine a film like Frozen being written in any other way. But another consequence was a retreat of visual imagination. When the eye no longer comes first, it’s harder for animators to create sequences that push against the boundaries of the medium. Over time, the movies start to look more or less the same, with similar character designs moving through beautifully rendered backgrounds that become ever more photorealistic for no particular reason.

The most heartening development in animation in recent years, which we’ve seen in Inside Out and Zootopia and now Moana, is the movement back toward a kind of animated feature that isn’t afraid to play with how it looks. Inside Out—which I think is the best movie Pixar has ever made—remains the gold standard, a film with a varied, anarchic style and amazing character design that still tells an emotionally effective story. Zootopia is more conventionally structured, but sequences like the chase through Little Rodentia are thrillingly aware of the possibilities of scale. Moana, in turn, may follow all the usual beats, but it’s also more episodic than usual, with self-contained sequences that seem to have been developed for their visual possibilities. I’m thinking, in particular, of the scenes with the pygmy Kakamora pirates and the encounter with Jermaine Clement’s giant coconut crab Tamatoa. You could lift these parts out and replace them with something else, and the rest of the story would be pretty much the same. For most movies, this would be a criticism, but there’s something about the episodic structure that allows animation to flourish, because each scene can be treated as a work of art in itself. Think, for instance, of Pinocchio, and how the plot wanders from Stromboli to Pleasure Island to Monstro almost at fancy. If it were made again today, the directors would probably get notes about how they should “establish” Monstro in the first act. But its dreamlike procession of wonders is what we remember the most fondly, and it’s exactly the quality that a conventional script would kill.

The fact that Disney and Pixar are rediscovering this sort of loose, shaggy energy is immensely promising, and I’m not entirely sure how it happened. (It doesn’t seem to be uniformly the case, either: Finding Dory was a lovely movie, but it was plotted to within an inch of its life.) Pinning down the cause becomes even tricker when we remember that all of these movies are in production at the same time. If so many storytelling tricks seem to recur—like the opening scene that shows the protagonist as a child, or the reveal in the third act that an apparently friendly character is really a bad guy—it’s probably because the same people were giving notes or actively engaged in multiple stories for years. Similarly, the move toward episodic structure may be less a conscious decision than the result of an atmosphere of experimentation that has started to permeate the studio. I’d love to think that it might be due to the influence through John Lasseter of Hayao Miyazaki, who thinks naturally in the language of dreams. The involvement of strong songwriters like Robert and Kristen Lopez and Lin-Manuel Miranda may also play a part: when you’ve got a great song at the heart of a scene, you’re more likely to think of visuals that rise to the level of the music. Another factor may be the rise of animators, like Moana producer Osnat Shurer, who came up through the ranks in the Pixar shorts, which are more willing to take stylistic risks. Put them all together with veteran directors like Ron Clements and John Musker, and you’ve got a recipe for self-contained scenes that push the envelope within a reliable formula.

But the strongest possibility of all, I think, is that we’re seeing what happens when the Pixar and Disney teams begin to work side by side. It’s been exactly ten years since Pixar was acquired by its parent company, which is just about the right amount of time for a cultural exchange to become consistently visible onscreen. The two divisions seem as if they’re trying to outdo each other, and the most obvious way is to come up with visually stunning sequences. This kind of competition will naturally manifest itself on the visual end: it’s hard for two teams of writers to keep an eye on each other, and any changes to the story won’t be visible until the whole thing is put together, while it’s likely that every animator has a good idea of what everybody else is doing. (Pixar headquarters itself was designed to encourage an organic exchange of ideas, and while it’s a long drive from Emeryville to Burbank, even that distance might be a good thing—it allows the divisions to compete on the basis of finished scenes, rather than works in progress.) It isn’t a foolproof method, and there will inevitably come a day when one studio or the other won’t overcome the crisis that seems to befall every animated feature halfway through production. But if you wanted to come up with a system that would give animators an incentive to innovate within the structure of a decent script, it’s hard to imagine a better one. You’ve got separate teams of animators trying to top each other, as they did on Alice, and a parent studio that has figured out how to make those episodes work as part of a story. That’s a great combination. And I can’t wait to see what they do next.

The prankster principle

In an interview with McKinsey Quarterly, Ed Catmull of Pixar was recently asked: “How do you, as the leader of a company, simultaneously create a culture of doubt—of being open to careful, systematic introspection—and inspire confidence?” He replied:

The fundamental tension [at Pixar] is that people want clear leadership, but what we’re doing is inherently messy. We know, intellectually, that if we want to do something new, there will be some unpredictable problems. But if it gets too messy, it actually does fall apart. And adhering to the pure, original plan falls apart, too, because it doesn’t represent reality. So you are always in this balance between clear leadership and chaos; in fact that’s where you’re supposed to be. Rather than thinking, “Okay, my job is to prevent or avoid all the messes,” I just try to say, “well, let’s make sure it doesn’t get too messy.”

Which sounds a lot like the observation from the scientist Max Delbrück that I never tire of quoting: “If you’re too sloppy, then you never get reproducible results, and then you never can draw any conclusions; but if you are just a little sloppy, then when you see something startling, you [can] nail it down…I called it the ‘Principle of Limited Sloppiness.’”

Most artists are aware that creativity requires a certain degree of controlled messiness, and scientists—or artists who work in fields where science and technology play a central role, as they do at Pixar—seem to be particularly conscious of this. As the zoologist John Zachary Young said:

Each individual uses the store of randomness, with which he was born, to build during his life rules which are useful and can be passed on…We might therefore take as our general picture of the universe a system of continuity in which there are two elements, randomness and organization, disorder and order, if you like, alternating with one another in such a fashion as to maintain continuity.

I suspect that scientists feel compelled to articulate this point so explicitly because there are so many other factors that discourage it in the pursuit of ordinary research. Order, cleanliness, and control are regarded as scientific virtues, and for good reason, which makes it all the more important to introduce a few elements of disorder in a systematic way. Or, failing that, to acknowledge the usefulness of disorder and to tolerate it to a certain extent.

When you’re working by yourself, you find that both your headspace and your workspace tend to arrive at whatever level of messiness works best for you. On any given day, the degree of clutter in my office is more or less the same, with occasional deviations toward greater or lesser neatness: it’s a nest that I’ve feathered into a comfortable setting for productivity—or inactivity, which often amounts to the same thing. It’s tricker when different personalities have to work together. What sets Pixar apart is its ability to preserve that healthy alternation between order and disorder, while still releasing a blockbuster movie every year. It does this, in part, by limiting the number of feature films that it has in production at any one time, and by building in systems for feedback and deconstruction, with an environment that encourages artists to start again from scratch. There’s also a tradition of prankishness that the company has tried to preserve. As Catmull says:

For example, when we were building Pixar, the people at the time played a lot of practical jokes on each other, and they loved that. They think it’s awesome when there are practical jokes and people do things that are wild and crazy…Without intending to, the culture slowly shifts. How do you keep the shift from happening? I can’t go out and say, “Okay, we’re going to organize some wild and crazy activities.” Top-down organizing of spontaneous activities isn’t a good idea.

It’s hard to scale up a culture of practical jokes, and Pixar has faced the same challenges here as elsewhere. The mixed outcomes of Brave and, to some extent, The Good Dinosaur show that the studio isn’t infallible, and a creative process that depends on a movie sucking for three out of four years can run into trouble when you shift that timeline. But the fact that Pixar places so much importance on this kind of prankishness is revealing in itself. It arises in large part from its roots in the movies, which have been faced with the problem of maintaining messiness in the face of big industrial pressures almost from the beginning. (Orson Welles spoke of “the orderly disorder” that emerges from the need to make quick decisions while moving large amounts of people and equipment, and Stanley Kubrick was constantly on the lookout for collaborators like Ken Adam who would allow him to be similarly spontaneous.) There’s a long tradition of pranks on movie sets, shading imperceptibly from the gags we associate with the likes of George Clooney to the borderline insane tactics that Werner Herzog uses to keep that sense of danger alive. The danger, as Herzog is careful to assure us, is more apparent than real, and it’s more a way of fruitfully disordering what might otherwise become safe and predictable. But just by the right amount. As the artist Frank Stella has said of his own work: “I disorder it a little bit or, I should say, I reorder it. I wouldn’t be so presumptuous to claim that I had the ability to disorder it. I wish I did.”

Choose life

Note: Every Friday, The A.V. Club, my favorite pop cultural site on the Internet, throws out a question to its staff members for discussion, and I’ve decided that I want to join in on the fun. This week’s topic: “What show did you stop watching after a character was killed off?”

Inside Out is an extraordinary film on many levels, but what I appreciated about it the most was the reminder it provides of how to tell compelling stories on the smallest possible scale. The entire movie turns on nothing more—or less—than a twelve-year-old girl’s happiness. Riley is never in real physical danger; it’s all about how she feels. These stakes might seem relatively low, but as I watched it, I felt that the stakes were infinite, and not just because Riley reminded me so much of my own daughter. By the last scene, I was wrung out with emotion. And I think it stands as the strongest possible rebuke to the idea, so prevalent at the major studios, that mainstream audiences will only be moved or excited by stories in which the fate of the entire world hangs in the balance. As I’ve noted here before, “Raise the stakes” is probably the note that writers in Hollywood get the most frequently, right up there with “Make the hero more likable,” and its overuse has destroyed their ability to make such stories meaningful. When every superhero movie revolves around the fate of the entire planet, the death of six billion people can start to seem trivial. (The Star Trek reboot went there first, but even The Force Awakens falls into that trap: it kills off everyone on the Hosnian System for the sake of a throwaway plot point, and it moves on so quickly that it casts a pall over everything that follows.)

The more I think about this mindless emphasis on raising the stakes, the more it strikes me as a version of a phenomenon I’ve discussed a lot on this blog recently, in which big corporations tasked with making creative choices end up focusing on quantifiable but irrelevant metrics, at the expense of qualitative thinking about what users or audiences really need. For Apple, those proxy metrics are thinness and weight; for longform journalism, it’s length. And while “raising the stakes” isn’t quite as quantitative, it sort of feels that way, and it has the advantage of being the kind of rule that any midlevel studio employee can apply with minimal fear of being wrong. (It’s only when you aggregate all those decisions across the entire industry that you end up with movies that raise the stakes so high that they turn into weightless abstractions.) Saying that a script needs higher stakes is the equivalent of saying that a phone needs to be thinner: it’s a way to involve the maximum number of executives in the creative process who have no business being there in the first place. But that’s how corporations work. And the fact that Pixar has managed to avoid that trap, if not always, then at least consistently enough for the result to be more than accidental, is the most impressive thing about its legacy.

A television series, unlike a studio franchise, can’t blow up the world on a regular basis, but it can do much the same thing to its primary actors, who are the core building blocks of the show’s universe. As a result, the unmotivated killing of a main character has become television’s favorite way of raising the stakes—although by now, it feels just as lazy. As far as I can recall, I’ve never stopped watching a show solely because it killed off a character I liked, but I’ve often given up on a series, as I did with 24 and Game of Thrones and even The Vampire Diaries, when it became increasingly clear that it was incapable of doing anything else. Multiple shock killings emerge from a mindset that is no longer able to think itself into the lives of its characters: if you aren’t feeling your own story, you have no choice but to fall back on strategies for goosing the audience that seem to work on paper. But almost without exception, the seasons that followed would have been more interesting if those characters had been allowed to survive and develop in honest ways. Every removal of a productive cast member means a reduction of the stories that can be told, and the temporary increase in interest it generates doesn’t come close to compensating for that loss. A show that kills characters with abandon is squandering narrative capital and mortgaging its own future, so it’s no surprise if it eventually goes bankrupt.

A while back, Bryan Fuller told Entertainment Weekly that he had made an informal pledge to shun sexual violence on Hannibal, and when you replace “rape” with “murder,” you get a compelling case for avoiding gratuitous character deaths as well:

There are frequent examples of exploiting rape as low-hanging fruit to have a canvas of upset for the audience…“A character gets raped” is a very easy story to pitch for a drama. And it comes with a stable of tropes that are infrequently elevated dramatically, or emotionally. I find that it’s not necessarily thought through in the more common crime procedurals. You’re reduced to using shorthand, and I don’t think there can be a shorthand for that violation…And it’s frequently so thinly explored because you don’t have the real estate in forty-two minutes to dig deep into what it is to be a victim of rape…All of the structural elements of how we tell stories on crime procedurals narrow the bandwidth for the efficacy of exploring what it is to go through that experience.

And I’d love to see more shows make a similar commitment to preserving their primary cast members. I’m not talking about character shields, but about finding ways of increasing the tension without taking the easy way out, as Breaking Bad did so well for so long. Death closes the door on storytelling, and the best shows are the ones that seem eager to keep that door open for as long as possible.

Insider awards, outsider art

I really have no business writing about the Oscars at all. My curtailed moviegoing habits these days mean that I only saw one of the Best Picture nominees—Mad Max: Fury Road, which was awesome—and for all my good intentions, I haven’t yet managed to catch up with the others at home. (My wife is a journalist, and like all her peers, she’s been a passionate member of team Spotlight ever since she saw the earliest photos of the cast’s painfully accurate khakis, brown shoes, and blue button-down shirts.) I can’t even write about Chris Rock’s monologue, since I was putting my daughter to bed when it aired, although the rest of the telecast struck me as the most professional ceremony in years: it hit its marks and moved like clockwork with a minimum of cringeworthiness, even if there weren’t many memorable moments. The ongoing debate about diversity and representation in popular culture is an important one, and it’s going to be even more central to my life and this blog as I continue working on Astounding, which raises huge questions about our default assumptions about the stories we tell. But today, I’d like to focus on just one issue. Why, in the name of all that is good and holy, wasn’t Inside Out nominated for Best Picture?

Because it’s a real mystery. Inside Out was one of the five most successful films at the domestic box office over the last calendar year, and it was the second most highly rated movie over the same period on Rotten Tomatoes, coming in behind Fury Road by just a hair. (It actually has a higher unadjusted score, but falls back a notch because it had fewer total reviews.) It also comes at the end of a stretch in which the Academy has been uncharacteristically willing to find room for animated features in the Best Picture race, as well as in their own category—as long as they’re made by Pixar. And Inside Out is the best Pixar movie ever made outside the Toy Story franchise, or at least the most visually and narratively inventive: its rousing aesthetic freedom is a reminder that even the best recent animated movies have been bound by gravity and mindlessly realistic texture mapping. Yet in a year in which the Academy Awards embraced unconventional nominees without regard to genre, from Mad Max to The Martian, Inside Out didn’t make the cut. And since there were only eight nominees, there was ample room for two more, according to a confusing sliding scale that I don’t even think most awards buffs understand. It wouldn’t have had to knock any other deserving movies out of the way: there was a slot right there waiting for it. But it was nowhere in sight.

This might seem like a moot point for a movie that won the Oscar for Best Animated Feature, made a ton of money, and choked up audiences worldwide. (My wife cried so much when we watched it that she practically went into anaphylactic shock.) But the larger implications are worth raising. It’s tough to analyze the collective psychology behind something like the Oscar nominations, which is why the problem of racism in Hollywood has been so difficult to address: it’s less the result of obvious structural shortcomings than an emergent property arising from countless small decisions made by players acting independently. When you try to find a solution, it slips through your fingers. Still, when the industry votes together, inclinations that might pass unseen on the individual level suddenly become all too visible. And in the case of animated features, when you amplify those tendencies to a point where they result in a concrete outcome, like a nomination or lack thereof, it’s obvious that a lot of voters find something vaguely suspect about animation itself. Thanks in a large part to its history as a children’s medium, it still feels like kid’s stuff, despite so much evidence to the contrary—or the fact that studios are increasingly dependent on a global audience for movies that are either animated or might as well be. It’s treated like outsider art, maybe because it naturally tends to attract visionary weirdos who wouldn’t be comfortable anywhere else.

This isn’t the Academy’s only blind spot: it also doesn’t much care for subtitles, sequels, or movies that fail to break even. But when you take into account the usual inverse relationship between artistic merit and job creation, the reluctance to recognize animated features as playing a grownup’s game is even harder to justify: these movies can take half a decade to make, employ hundreds of people, and involve the solution of many intractable creative and technical problems. (In fact, the development of Inside Out appears to have been exceptionally difficult: Pete Docter has spoken of how the entire script was junked halfway through, once they realized that Joy had to go on her adventure with Sadness, rather than Fear. It’s the best example imaginable of the Andrew Stanton approach—“The films still suck for three out of the four years it takes to make them”—succeeding, for once, to a spectacular degree.) And what makes Inside Out such an instructive test case is that everything else was lined up in its favor. It was moving, formally elegant, incredibly entertaining, and it wasn’t a sequel, the last of which probably counted against Toy Story 2, which was also unambiguously the biggest critical and box office success of its year. For an animated film not just to get nominated, but to win, would require both a masterpiece and a sea change in how such movies are regarded by the industry that relies on them so much. And if that ever happens, it’ll be a reason to be joyful.

The time factor

Earlier this week, my daughter saw Toy Story for the first time. Not surprisingly, she loved it—she’s asked to watch it three more times in two days—and we’ve already moved on to Toy Story 2. Seeing the two movies back to back, I was struck most of all by the contrast between them. The first installment, as lovely as it is, comes off as a sketch of things to come: the supporting cast of toys gets maybe ten minutes total of screen time, and the script still has vestiges of the villainous version of Woody who appeared in the earlier drafts. It’s a relatively limited film, compared to the sequels. Yet if you were to watch it today without any knowledge of the glories that followed, you’d come away with a sense that Pixar had done everything imaginable with the idea of toys who come to life. The original Toy Story feels like an exhaustive list of scenes and situations that emerge organically from its premise, as smartly developed by Joss Whedon and his fellow screenwriters, and in classic Pixar fashion, it exploits that core gimmick for all it’s worth. Like Finding Nemo, it amounts to an anthology of all the jokes and set pieces that its setting implies: you can practically hear the writers pitching out ideas. And taken on its own, it seems like it does everything it possibly can with that fantastic concept.

Except, of course, it doesn’t, as two incredible sequels and a series of shorts would demonstrate. Toy Story 2 may be the best example I know of a movie that takes what made its predecessor special and elevates it to a level of storytelling that you never imagined could exist. And it does this, crucially, by introducing a new element: time. If Toy Story is about toys and children, Toy Story 2 and its successor are about what happens when those kids become adults. It’s a complication that was inherent to its premise from the beginning, but the first movie wasn’t equipped to explore it—we had to get to know and care about these characters before we could worry about what would happen after Andy grew up. It’s a part of the story that had to be told, if its assumptions were to be treated honestly, and it shows that the original movie, which seemed so complete in itself, only gave us a fraction of the full picture. Toy Story 3 is an astonishing achievement on its own terms, but there’s a sense in which it only extends and trades on the previous film’s moment of insight, which turned it into a franchise of almost painful emotional resonance. If comedy is tragedy plus time, the Toy Story series knows that when you add time to comedy, you end up with something startlingly close to tragedy again.

And thinking about the passage of time is an indispensable trick for creators of series fiction, or for those looking to expand a story’s premise beyond the obvious. Writers of all kinds tend to think in terms of unity of time and place, which means that time itself isn’t a factor in most stories: the action is confined within a safe, manageable scope. Adding more time to the story in either direction has a way of exploding the story’s assumptions, or of exposing fissures that lead to promising conflicts. If The Godfather Part II is more powerful and complex than its predecessor, it’s largely because of its double timeline, which naturally introduces elements of irony and regret that weren’t present in the first movie: the outside world seems to break into the hermetically sealed existence of the Corleones just as the movie itself breaks out of its linear chronology. And the abrupt time jump, which television series from Fargo to Parks and Recreation have cleverly employed, is such a useful way of advancing a story and upending the status quo that it’s become a cliché in itself. Even if you don’t plan on writing more than one story or incorporating the passage of time explicitly into the plot, asking yourself how the characters would change after five or ten years allows you to see whether the story depends on a static, unchanging timeframe. And those insights can only be good for the work.

This also applies to series in which time itself has become a factor for reasons outside anyone’s control. The Force Awakens gains much of its emotional impact from our recognition, even if it’s unconscious, that Mark Hamill is older now than Alec Guinness was in the original, and the fact that decades have gone by both within the story’s universe and in our own world only increases its power. The Star Trek series became nothing less than a meditation on the aging of its own cast. And this goes a long way toward explaining why Toy Story 3 was able to close the narrative circle so beautifully: eleven years had passed since the last movie, and both Andy and his voice actor had grown to adulthood, as had so many of the original film’s fans. (It’s also worth noting that the time element seems to have all but disappeared from the current incarnation of the Toy Story franchise: Bonnie, who owns the toys now, is in no danger of growing up soon, and even if she does, it would feel as if the films were repeating themselves. I’m still optimistic about Toy Story 4, but it seems unlikely to have the same resonance as its predecessors—the time factor has already been fully exploited. Of course, I’d also be glad to be proven wrong.) For a meaningful story, time isn’t a liability, but an asset. And it can lead to discoveries that you didn’t know were possible, but only if you’re willing to play with it.

Alice in Disneyland

A few weeks ago, I noted that watching the Disney movies available for streaming on Netflix is like seeing an alternate canon with high points like Snow White and Pinocchio stripped away, leaving marginal—but still appealing—films like Robin Hood and The Aristocats. Alice in Wonderland, which my daughter and I watched about ten times this week, lies somewhere in the middle. It lacks the rich texture of the earlier masterpieces, but it’s obviously the result of a lot of work and imagination, and much of it is wonderful. In many respects, it’s as close as the Disney studio ever got to the more anarchic style of the Warner Bros. cartoons, and when it really gets cooking, you can’t tear your eyes away. Still, it almost goes without saying that it fails to capture, or even to understand, the appeal of the original novels. Part of this is due to the indifference of the animators to anything but the gag of the moment, a tendency that Walt Disney once fought to keep in check, but which ran wild as soon as his attention was distracted by other projects. I love the work of the Nine Old Men as much as anyone, but it’s also necessary to acknowledge how incurious they could often appear about everything but animation itself, and how they seemed less interested in capturing the tone of authors like Lewis Carroll, A.A. Milne, or Kenneth Grahame than in shoehorning those characters into the tricks they knew. And it was rarely more evident than it is here.

What really fascinates me now about Alice in Wonderland is how it represents a translation from one mode of storytelling—and even of how to think about narrative itself—into another. The wit of Carroll’s novels isn’t visual, but verbal and logical: as I noted yesterday, the first book emerges from the oral fairy tale tradition, as enriched by the author’s gifts for paradox, parody, and wordplay. The Disney studio of this era, by contrast, wasn’t used to thinking in words, but in pictures. Movies were planned out as a series of thumbnail sketches on a storyboard, which naturally emphasized sight gags and physical comedy over dialogue. For the most part, Carroll’s words are preserved, and they often benefit from fantastic voice performances, but most of the scenes treat them as little more than background noise. My favorite example here is the Mad Tea Party. When I watch it again now, it strikes me as a dazzling anthology of visual puns, some of them brilliant, built around the props on the table: you can almost see the animators at the drawing board pitching out the gags, which follow one another so quickly that it makes your head spin. The result doesn’t have much to do with Lewis Carroll, and none of the surviving verbal jokes really land or register, but it works, at least up to a point, as a visual equivalent of the density of the book’s prose.

But it doesn’t really build to anything, and like the movie itself, it just sort of ends. As Ward Kimball once said to Leonard Maltin: “It suffered from too many cooks—directors. Here was a case of five directors each trying to top the other guy and make his sequence the biggest and craziest in the show. This had a self-canceling effect on the final product.” Walt Disney himself seems to have grasped this, and I’d like to think that it contributed to his decision, a few years later, to subordinate all of Sleeping Beauty to the style of the artist Eyvind Earle. (That movie suffers from the same indifference to large chunks of the plot that we see elsewhere in Disney—neither Aurora nor Prince Philip even speak for the second half of the film, since the animators are clearly much more interested in Malificent and the three good fairies—but we’re so caught up in the look and music that we don’t really care.) Ultimately, the real solution lay in a more fundamental shift in the production process, in which the film was written up first as a screenplay rather than as a series of storyboards. This model, which is followed today by nearly all animated features, was a relatively late development. And to the extent that we’ve seen an expansion of the possibilities of plot, emotion, and tone in the ongoing animation renaissance, it’s thanks to an approach that places more emphasis on figuring out the overall story before drilling down to the level of the gag.

That said, there’s a vitality and ingenuity to Alice in Wonderland that I miss in more recent works. Movies like Frozen and the Pixar films are undeniably spectacular, but it’s hard to recall any moments of purely visual or graphic wit of the kind that fill the earlier Disney films so abundantly. (The exception, interestingly, is The Peanuts Movie, which seems to have benefited by regarding the classic Schulz strips as a sort of storyboard in themselves, as well as from the challenges of translating the flat style of the originals into three dimensions.) An animated film built around a screenplay and made with infinite technological resources starts to look more or less like every other movie, at least in terms of its staging and how all the pieces fit together, while a film that starts with a storyboard often has narrative limitations, but makes up for it with a kind of local energy that doesn’t have a parallel in any other medium. The very greatest animated films, like My Neighbor Totoro, somehow manage to have it both ways, and the example of Miyazaki suggests that real secret is to have the movie conceived by a single visionary who also knows how to draw. Given the enormous technical complexity of contemporary animation, that’s increasingly rare these days, and it’s true that some of the best recent Pixar movies, like Toy Story 3, represent the work of directors who don’t draw at all. But I’d love to see a return to the old style, at least occasionally—even if it isn’t everyone’s cup of tea.

Beyond good and evil

First, a toddler movie update. After a stretch in which my daughter watched My Neighbor Totoro close to a hundred times, she’s finally moved on to a few other titles: now she’s more into Ponyo, Hayao Miyazaki’s other great masterpiece for children, and, somewhat to my surprise, the original Disney release of The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh. All, thankfully, are movies that I’m happy to watch on a daily basis, and seeing them juxtaposed together so often has allowed me to draw a few comparisons. Totoro still strikes me as a perfect movie, with a entire world of loveliness, strangeness, and fine observation unfolding from a few basic premises. Ponyo is a little messier, with a glorious central hour surrounded on both sides with material that doesn’t seem as fully developed, although it’s not without its charms. And Winnie the Pooh impresses me now mostly as an anthology of good tricks, gags, and bits of business, as perfected over the decades by the best animators in the world. It’s sweet and funny, but more calculated in its appeal than its source, and although it captures many of the pleasures of the original books, it misses something essential in their tone. (Really, the only animator who could give us a faithful version of Milne’s stories is Miyazaki himself.)

And none of them, tellingly, has any villains. Beatrix hasn’t been left entirely innocent of fictional villainy, and she already knows that—spoiler alert—Hans is “the bad guy” and Kristof is “the good guy” based on her limited exposure to Frozen. Yet I’ve always suspected that the best children’s movies are the ones that hold the viewer’s attention, regardless of age, without resorting to manufactured conflicts. You could divide the Pixar films into two categories based on which ones lean the heaviest on scripted villains, and you often find that the best of them avoid creating characters whom we’re only supposed to hate. The human antagonists in the Toy Story films and Finding Nemo are more like impersonal forces of nature than deliberate enemies, and I’ve always been a little uneasy about The Incredibles, as fantastic as so much of it is, simply because its villain is so irredeemably loathsome. There are always exceptions, of course: Toy Story 3 features one of the most memorable bad guys in any recent movie, animated or otherwise. But if children’s films that avoid the easy labels of good guys and bad guys tend to be better than average, that’s less a moral judgment than a practical one: in order to tell an interesting story without an obvious foil, you have to think a little harder. And it shows.

That said, there’s an obvious contradiction here. As I’ve stated elsewhere, when I tell my daughter fairy tales, I tend to go for the bloodiest, least sanitized versions I can find. There’s no shortage of evil in the Brothers Grimm, and the original stories go far beyond what most children’s movies are willing to show us. The witch in “Hansel and Gretel” is as frightening a monster as any I know, and I still feel a chill when I read her first line aloud. The wolf gobbles up Little Red Riding Hood and her grandmother whole, and as his punishment, he gets killed with an axe and sliced open with sewing shears. (At least, that’s what happens in the version I’ve been reading: in the original, Little Red Riding Hood herself proposes that the wolf’s belly be filled with heavy stones.) The queen in “Snow White” attempts to kill the title character no fewer than three times, first by strangling her with a lace bodice, then with a poisoned comb, before finally resorting to the apple to finish the job. And when you sanitize these stories, you rob them of most of their meaning. As I noted in my original post on the subject: “A version of ‘Little Red Riding Hood’ in which the wolf doesn’t eat the grandmother doesn’t just trivialize the wolf, but everybody else involved, and it’s liable to strike both child and parent as equally pointless.”

So why do I value fairy tales for their unflinching depictions of evil, while equally treasuring children’s films in which nothing bad happens at all? I could justify this in all kinds of ways, but I keep returning to a point that I’ve made here before, which is that the only moral value I feel like inculcating in my daughter—at least for now—is a refusal to accept shoddy or dishonest storytelling. Miyazaki and the Brothers Grimm lie on opposite ends of a spectrum, but they’re unified by their utter lack of cynicism. One might be light, the other dark, but they’re both telling the stories they have in the most honest way they can, and they don’t feel obliged to drum up our interest using artificial means. In Miyazaki, it’s because the world is too magical for us to need a bad guy in order to care about it; in the Brothers Grimm, it’s because the world is already so sinister, down to its deepest roots, and the story is less about giving us a disposable antagonist than in confronting us with our most fundamental fears. When you compare it to the children’s movies that include a bully or a bad guy who exists solely to drive the plot along, you see that Totoro and “Hansel and Gretel” have more in common with each other than with their lesser counterparts. There’s good in the world as well as evil, and I don’t plan on sheltering my daughter from either one. But I’m going to shelter her from bad storytelling for as long as I can.

Totoro and I

A few months ago, in a post about the movies I’ve watched the most often, I made the following prediction about my daughter:

Once Beatrix is old enough, she’ll start watching movies, too, and if she’s anything like most kids I know, she’ll want to watch the same videos over and over. I fully expect to see My Neighbor Totoro or the Toy Story films several hundred times over the next few years—at least if all goes according to plan.

As it turns out, I was half right. Extrapolating from recent trends, I’ll definitely end up watching Totoro a hundred times or more—but it will only take a few months. I broke it out for the first time this week, as Beatrix and I were both getting over a cold, which, combined with a chilly week in Oak Park, kept both of us mostly inside. When I hit the play button, I wasn’t sure how she’d respond. But she sat transfixed for eighty minutes. Since then, she’s watched it at least ten times all the way through, to the point where I’ve had to negotiate a limit of one viewing per day. And although I couldn’t be happier, and I can’t imagine another movie I’d be more willing to watch over and over again, I occasionally stop to wonder what I’ve awakened.

Screen time for children can be a touchy subject, but after holding out for more than two years, we’re finally allowing Beatrix to watch videos on a regular basis. Along with her daily Totoro fix, she’ll spend half an hour on her mommy’s phone in the morning, usually taking in Sesame Street or Frozen clips on YouTube. (As a parenting tip, I’d also recommend investing in an inexpensive portable DVD player, like the sturdy one I recently picked up by Sylvania. It’s better than a phone, since it allows for a degree of parental control and resists restless skipping from one video to the next, and unlike a television, it can be tucked out of sight when you’re done, which cuts down on the number of demands.) Whenever possible, I like to sit with her while we’re watching, asking her to comment on the action or to tell me what she sees. And Totoro, in particular, has awakened her imagination: she’s already pretending to gather acorns around the house, and she identifies strongly with the two little girls. For my part, I feel the same way about the father, who may be the best parent in any animated film, and whenever I find myself at a loss, I’ve started to ask myself: “What would the dad in Totoro do?”

And while it’s possible that Beatrix would have latched onto whatever I decided to show her, I’d like to think that there’s something about Totoro that makes it the right movie at the right time. As I’ve noted before, its appeal can be hard to explain. Pixar’s brand of storytelling can be distilled into a set of rules—I’ve said elsewhere that its movies, as wonderful as they can be, feel like the work of a corporation willing itself into the mind of a child—and we’ve seen fine facsimiles in recent years from DreamWorks and Disney Animation. But Miyazaki remains indefinable. The wonder of Totoro is that Totoro himself only appears for maybe five minutes: the rest is a gentle, fundamentally realistic look at the lives of two small children, and up until the last act, whatever magic we see could easily be a daydream or fantasy. Yet it’s riveting all the way through, and its attention to detail rewards multiple viewings. Every aspect of life in the satoyama, or the Japanese countryside, is lovingly rendered, and there are tiny touches in every frame to tickle a child’s curiosity, or an adult’s. It’s a vision of the world that I want to believe, and it feels like a gift to my daughter, who I can only hope will grow up to be as brave as Mei and as kind as Satsuki.

Best of all, at a time when most children’s movies are insistently busy, it provides plenty of room for the imagination to breathe. In fact, its plot is so minimal—there are maybe six story beats, generously spaced—that I’m tempted to define the totoro as the basic unit of meaningful narrative for children. A movie like Ponyo is about 1.5 totoros; Spirited Away is 2; and Frozen or most of the recent Pixar films push it all the way up to 3. There’s nothing wrong with telling a complicated plot for kids, and one of the pleasures of the Toy Story films is how expertly they handle their dense storylines and enormous cast. But movement and color can also be used to cover up something hollow at the heart, until a film like Brave leaves you feeling as if you’ve been the victim of an elaborate confidence game. Totoro’s simplicity leaves no room for error, and even Miyazaki, who is as great a filmmaker as ever lived, was only able to do it once. (I still think that his masterpiece is Spirited Away, but its logic is more visible, a riot of invention and incident that provides a counterpoint to Totoro‘s sublime serenity.) If other films entice you with their surfaces, Totoro is an invitation to come out and play. And its spell lingers long after you’ve put away the movie itself.

The Toy Story of our lives

A few weeks ago, Pixar announced that Toy Story 4 is officially in production, with the dream team of John Lasseter, Pete Docter, Lee Unkrich, and Andrew Stanton advising the writing duo of Rashida Jones and Will McCormack. (I don’t doubt the talents of the latter two, but I still smile a little at the thought of that meeting: I’d like to think that it consisted mostly of four big, nerdy guys in Hawaiian shirts being inexplicably charmed by Jones’s pitch for the franchise.) Like many fans of what I’ve come to see as the best series of children’s films ever made, I’m tickled, but cautious. It’s not so much the fear that a mediocre fourth movie would undermine my feelings for the first three—heck, I’ve been through that process before. Rather, it’s the fact that a perfectly fine arrangement already exists, in the form of the animated shorts about these characters that Pixar has continued to produce. I’m not sure I need to see Toy Story 4, but I’d happily accept a run of shorts that went on forever, if it means we get more miniature masterpieces along the lines of Partysaurus Rex.

The nice thing about the Toy Story shorts is that they meet a particular need while leaving our memories of the movies untouched. Much of the appeal of these films comes from their almost frightening emotional resonance, and while it’s unfair to hold a short cartoon to the same standard, I love these characters so much that I’m glad just to be treated to a few brief vignettes of their lives. As we learned from Cars 2, cleverness alone can’t sustain an entire feature, but it’s more than enough to fill six minutes, and the format of the animated short allows Pixar to revel in a few crucial aspects of the franchise—its ingenuity and humor—while not having to strain for the intensity of feeling that the movies achieve. In that regard, it’s revealing that the longer specials, Toy Story of Terror and last night’s Toy Story That Time Forgot, tend to hit beats that we’ve seen before: the villain in the former feels more than a little like his counterpart in Toy Story 2, and the latter introduces an army of toys who don’t know that they’re toys, of which Buzz drily notes: “Incredible, isn’t it?”

More than anything else, this is what gives me pause at the prospect of Toy Story 4. The first three movies seem almost inevitable in the emotional ground they cover: the series gradually became a meditation on growing up, and now that Andy has gone off to college, it’s hard to envision what remains to be told. Still, I’ve been surprised before, and if anything, Toy Story That Time Forgot serves as a reminder of how much feeling can still be plumbed from these characters and their situations. For most of its length, it’s a cute diversion, maybe a notch below the best of the shorts so far. (It lost me a little during its long middle section, which takes place entirely within the plastic world of the Battlesaurs: a lot of the fun of these stories arises from the element of scale, with the toys’ adventures set against the baseboards and table legs of the larger everyday world, and we lose this when the action unfolds in artificial surroundings.) Yet by the end, I was unexpectedly touched by its message, like that of The Lego Movie, which implies that toys find their greatest meaning when they surrender to a child’s imagination.

Obviously, it’s hard to separate my response from my own experience as a father, which is a fairly recent development—my daughter wasn’t even born when Toy Story 3 was released. And I see a lot of Bonnie in Beatrix. She’s just arriving at the age when she starts to tell stories involving her toys that I couldn’t have anticipated: she’ll sling her Hello Kitty purse over her shoulder and announce that she’s taking the train to work, or explain that Mr. Bear needs to have his diaper changed, and she’s already beginning to spin private narratives using the figures in our plastic nativity set. And even if my feelings have been shaped by where I happen to be in my own life, I can’t help but think that if there’s one last region for the series to explore, it’s here—in the strange closeness that emerges between a child, her toys, and her parents. (So far, the series has only given us hints of this, notably in the form of the intriguing clues, which can’t be dismissed, that the little girl who gave away Jessie the Cowgirl grew up to be Andy’s mom.) Toy Story has a lot to say about small children, but it’s been oddly indifferent so far to families. That’s the fourth movie I’d like to see, and I’ll tell this to anyone who wants to listen, even if it means I have to take a meeting with Rashida Jones.

Blinn’s Law and the paradox of efficiency

Note: I seem to have come down with a touch of whatever stomach bug my daughter had this week, so I’m taking the day off. This post was originally published, in a somewhat different form, on August 9, 2011.

As technology advances, rendering time remains constant.

—Blinn’s Law

Why isn’t writing easier? Looking at the resources that contemporary authors have at their disposal, it’s easy to conclude that we should all be perfect writing machines. Word processing software, from WordStar to Scrivener, has made the physical process of writing more streamlined than ever; Google and Amazon have given us access to a world of information that would have been inconceivable even fifteen years ago; and research, editing, and revision have been made immeasurably more efficient. And yet writing itself doesn’t seem all that much less difficult than before. The amount of time a professional novelist needs to spend writing each day—let’s say three or four hours—hasn’t decreased much since Trollope, and for most of us, it still takes a year or two to write a decent novel.

So what happened? In some ways, it’s an example of the paradox of labor-saving devices: instead of taking advantage of our additional leisure time, we create more work for ourselves. It also reflects the fact that the real work of writing a novel is rarely connected to how fast you can type. But I prefer to think of it as a variation on Blinn’s Law. As graphics pioneer James Blinn first pointed out, in animation, rendering time remains constant, even as computers get faster. An artist gets accustomed to waiting a certain number of hours for an image to render, so as hardware improves, instead of using it to save time, he employs it to render more complex graphics. This is why rendering time at Pixar has remained essentially constant over the past fifteen years. (Although the difference between Toy Story and Cars 2, or even Brave, is a reminder that rendering isn’t everything.)

Similarly, whatever time I save by writing on a laptop rather than a manual typewriter is canceled out by the hours I spend making additional small changes and edits along the way. The Icon Thief probably went through eighteen substantial drafts before the final version was delivered to my publisher, an amount of revision and rewriting that would have been unthinkable without Word. Is the novel better as a result? On a purely technical level, yes. Is the underlying story more interesting than if I’d written it by hand? Probably not. Blinn’s Law tells us that the leaves and grass in the background of a shot will look increasingly great, but it says nothing about the quality of storytelling. Which seems to imply that the countless tiny changes that a writer like me makes to each draft are only a waste of effort.

And yet here’s the thing: I still needed all that time. No matter how efficient the physical side of the process becomes, it’s still desirable for a writer to live with a novel, or a studio to live with a movie, for at least a year or so. (In the case of a film like Frozen, that gestational period can amount to a decade or more.) For most of us, there seems to be a fixed developmental period for decent art, a minimum amount of time that a story needs to simmer and evolve. The endless small revisions aren’t the point: the point is that while you’re altering a word or shifting a paragraph here or there, the story is growing in your head in unexpected ways. Even as you fiddle with the punctuation, seismic changes are taking place. But for this to happen, you need to be at your desk for a certain number of hours. So what do we do in the meantime? We do what Pixar does: we render. That’s the wonderful paradox of efficiency: it allows us, as artists, to get the inefficiency we all need.

Toy Story of delight

Breaking Bad may be over, but last night, my wife and I watched what emphatically ranks as a close second in our most highly anticipated television events of the year: Toy Story of Terror, the first of what I hope will be many Pixar specials featuring the characters from my favorite animated franchise. Not surprisingly, I loved it, even if I’d rate it a notch below the sublime Partysaurus Rex. It’s constructed in the usual shrewd, slightly busy Pixar manner, with complication piled on complication, and it packs a startling amount of plot into a runtime of slightly over twenty minutes. A big part of the appeal of the Toy Story franchise has always been its narrative density: these aren’t long movies, but each installment, especially the latter two, is crammed with ideas, a tradition that the shorts have honored and maintained. And although it may not rank among the greatest holiday specials ever made, it gave me a hell of a lot of pleasure, mostly because I was delighted, as I always am, to see these characters again.

I’ve spoken frequently on this blog about the power of ensembles, which allow a television show to exploit different, surprising combinations of characters, but I don’t think I’ve really delved into its importance in film, which operates under a different set of constraints. Instead of multiple seasons, you have, at best, a handful of installments, and often just one movie. A rich supporting cast can lead to many satisfactions in the moment—think of the ensembles in Seven Samurai, The Godfather, L.A. Confidential—but it also allows you to dream more urgently of what else might have taken place, both in the runtime of the movie itself and after the story ends. When a great ensemble movie is over, it leaves you with a sense of loss: you feel that the characters were doing other things beyond the edges of the frame, pairing off in unexpected ways, and you wish there were time for more. (It’s no accident that the franchises that inspire the most devoted fanfic communities, from Harry Potter to Star Trek, are the ones that allow fans to play with the widest range of characters.)

And I don’t think I’ve ever felt this so keenly as I have with the characters from Toy Story. Over the course of three films and a handful of shorts, the franchise has created dozens of memorable characters, and it’s remarkable how vividly even briefly glimpsed figures—Wheezy, the Chatter Telephone—are drawn. Part of this is due to the fact that toys advertise their personalities to us at once, and you can mine a lot of material from either underlining or subverting that initial impression, as in the case of Lots-o’-Huggin’ Bear, who stands as one of the most memorable movie villains of the last decade. But it’s also thanks to some sensational writing, directing, and voice acting in the established Pixar style, as well as the ingenuity of the setting and premise itself. At its best, the franchise is an adventure series crossed with a workplace comedy, and much of its energy comes from the idea of these toys, literally from different worlds, thrown together into the same playroom. Andy’s bedroom, or Bonnie’s, or any child’s, is a stage on which an endless number of stories can be told, and they don’t need to be spectacular: I’d be happy just to watch these toys hanging out all day.

That’s the mark of great storytelling, and as time goes on, I’ve begun to suspect that this may be the best movie trilogy I’ve ever seen. I’ve loved this series for a long time, but it wasn’t until Toy Story 2 came out that it took up a permanent place in my heart. At the time, I was working as an online movie critic, and I was lucky enough to see it at a preview screening—I almost typed “screaming,” which is a revealing typo—packed with kids. And I don’t think any movie has ever left me feeling happier on leaving the theater, both because the film itself was a masterpiece, and because I knew that every child in the world was going to see it. Ten years later, Toy Story 3 provided the best possible conclusion to the central story, and I don’t think I want any more movies, as much as I want to spend more time with these characters. But the decision to release additional shorts and specials was a masterstroke. For any other franchise, it might have seemed like a cash grab, but I can’t help but read it as an act of generosity: it gives us a little more, but not too much, of what we need. And it makes me a little envious of my own daughter, who, if all goes according to plan, will grow up with Woody, Buzz, Rex, and the rest, not just as beloved characters, but as friends.

A writer’s progress

Over the past few days, I’ve been engaged in a long conversation with my younger self, using what Stephen King has rightly called the only real form of time travel we have. Years ago, when I left my job in New York to become a professional writer, my first major project was a long novel about India. I spent two years writing and revising it in collaboration with an agent, only to abandon it unpublished in the end for reasons that I’ve described elsewhere. It was a bittersweet experience at best, one that taught me much of what I know about writing, while also leaving me with little to show for it, and as a result, I haven’t gone back and read that novel in a long time—more than four years, in fact. Now that I’ve finished Eternal Empire, however, I’ve got some time on my hands, and one of the first things I wanted to do, since I no longer have a book under contract, is go back and look at that early effort to see whether there’s anything there worth saving. And the prospect of reading this novel again after so long filled me with a lot of trepidation.

In some ways, I doubt I’ll ever have this kind of experience again. This first novel represents the very best that I could do at that time in my career: I lavished everything I had on it for two years of my life, and so it would be surprising, at least to me, if there wasn’t at least something worthwhile there. But I’ve changed a lot in the meantime, too. When I sat down to write my first book, it largely to prove to myself that I could do it at all: I’d never written an original novel before, unless you count the science-fiction epic I cranked out in the summer between seventh and eighth grade, and I’d suffered through several unfinished projects in the meantime. Today, the situation couldn’t be more different: I have something like 350,000 words of professional work behind me, and I’ve gone through the process of writing, cutting, and revising a manuscript with an editor twice, with a third time just around the corner. I’m a better, smarter writer now, and this is probably the only chance I’ll have to confront the best work of my early days with the detachment that four years of distance affords.

And while reading the novel again, I discovered something fascinating: this manuscript, which is the final version of a book that went through countless edits, revisions, and iterations, is basically as good as the first drafts I write today. It isn’t a bad novel by any means: there’s a lot of interesting material, some exciting scenes, and many extended passages of decent writing. But it’s clearly the work of a novice. Most chapters go on for longer than they should; I spell out motivations and subtext rather than leaving them to the reader; and, much to my embarrassment, I even have long sections of backstory. At the time, this was the novel I wanted to write, and since then, my tastes have changed and developed in certain ways, which is precisely how it should be. Yet here’s the funny thing: I still write chapters that are too long, spell things out too explicitly, and tell more than I should about a character’s background. The difference now is that I cut it, usually before I’ve even printed out a copy to mark up with a red pencil. And whatever mistakes that remain tend to be made, and addressed, more quickly.

Which gets me to an important point about progress. There’s no such thing as real progress in the arts, at least as far as storytelling is concerned, but there’s certainly room for an individual author to grow and improve over time—and the best thing that a writer can learn, as they say at Pixar, is that you need to be wrong fast. Sometimes I’m wrong only in my own head, while I’m working out a scene in my mind’s eye, and I’ve corrected the mistake long before I begin to type. More often, I need to write something out first and change it once I realize it isn’t working. But the fact that my first drafts now are as good as my final drafts of a few years ago implies, if nothing else, that I’ve accelerated the process, which is about all a writer can ask. I’m still fundamentally the same person I was when I wrote my first novel, but a lot more efficient, and I’ll be happy as long as I can continue in the same general direction. As David Belle, the founder of parkour, says: “First, do it. Second, do it well. Third, do it well and fast—that means you’re a professional.”

Flight, Wreck-It Ralph, and the triumph of the mainstream

At first glance, it’s hard to imagine two movies more different than Flight and Wreck-It Ralph. The former is an emphatically R-rated message movie with a refreshing amount of nudity, drug and alcohol abuse, and what used to be known as adult situations, in the most literal sense of the term; the latter is a big, colorful family film that shrewdly joins the latest innovations in animation and digital effects to the best of classic Disney. On the surface, they appeal to two entirely separate audiences, and as a result, you’d expect them to coexist happily at the box office, which is precisely what happened: both debuted this weekend to numbers that exceeded even the most optimistic expectations. (This is, in fact, the first weekend in a long time when my wife and I went to the movies on two consecutive nights.) Yet these two films have more in common than first meets the eye, and in particular, they offer an encouraging snapshot of Hollywood’s current potential for creating great popular entertainment. And even if their proximity is just a fluke of scheduling, it’s one that should hearten a lot of mainstream moviegoers.