Search Results

Heinlein’s index cards

I keep with me at all times 3 x 5 file cards on which I make notes—at my bedside, in my bath, at my dining table, at my desk, and everywhere, and I invariably have them on my person whenever I am away from home, whether for fifteen minutes or six months. An idea for a story is jotted down on such a card and presently is filed under an appropriate category, in my desk. When enough notes have accumulated around an idea to cause me to think of it as an emergent story, I pull those cards out of category files, assign a working title, and give it a file separator with the working title written on the index. Thereafter, new notes are added to the bundle as they occur to me. At the present time I am filing notes under sixteen categories and under fifty-three working titles.

A story may remain germinating for days only, or for years—two of my current working titles are more than twenty years old. But once I start to write a story the first draft usually is completed in a fairly short time. Thereafter I spend time as necessary in cutting, revising, and polishing. Then the opus is smooth-typed and sent to market.

—Robert A. Heinlein, quoted in Robert A. Heinlein: In Dialogue With His Century

Robert Heinlein’s five rules of writing

1. You must write.

2. You must finish what you write.

3. You must refrain from rewriting except to editorial order.

4. You must put it on the market.

5. You must keep it on the market until it is sold.—Robert A. Heinlein, in Of Worlds Beyond: The Science of Science Fiction Writing

The books and the wall

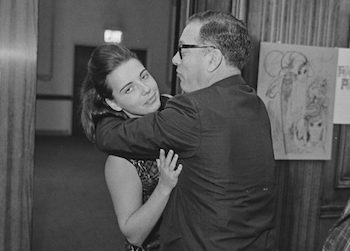

Yesterday, I published an essay titled “Asimov’s Empire, Asimov’s Wall” on the website Public Books, in which I discuss Isaac Asimov’s history of groping and engaging in other forms of unwanted touching with women at conventions, in the workplace, and in private over the course of many decades. It’s a piece that I’ve had in mind for a long time, and I’ve come to think of it as a lost chapter of Astounding, which I might well have included in the book if I had delivered the final draft a few months later than I actually did. (I’m also very glad that the article includes the image reproduced above, which I found after going through thousands of photos in the Jay Kay Klein archive.) The response online so far has been overwhelming, including numerous firsthand accounts of his behavior, and I hope it leads to more stories about Asimov, as well as others. There’s a lot that I deliberately didn’t cover here, and it deserves to be taken further in the right hands.

Onward and upward

Next week, I’ll be attending the 77th World Science Fiction Convention in Dublin, Ireland, which promises to be a lot of fun. Here’s my schedule as it currently stands:

- Thursday August 15, 3pm—”Current Politics Reflected in SFF”—Dr. Harvey O’Brien (M), Susan Connolly, Dr Douglas Van Belle, Alec Nevala-Lee—”SFF is probably the genre that best mirrors present day society. If we examine SFF in both visual media and books, what can we learn about current politics playing out? What might future generations surmise about us?”

- Friday August 16, 11:30am—”Continuing Relevance of Older SF”—Sue Burke (M), Alec Nevala-Lee, Aliza Ben Moha, Robert Silverberg, Joe Haldeman—”We are in a new millennium, a literal Brave New World. Surely much of the fiction of the 20th century no longer holds relevance? The panel will discuss the fiction of the past and how it can still be relevant in the 21st century. What lessons from older authors – such as Orwell, Asimov, Butler, Delany, Kafka, and Atwood – can we apply to our app-loaded, social media-driven age?”

- Friday August 16, 2019, 5pm—”Comparable Futurist Movements”—Alec Nevala-Lee (M), Gillian Polack, Jeanine Tullos Hennig, Shweta Taneja—”How influenced by Afrofuturism are other world futurist movements such as Sinofuturism, Nippofuturism and Gulf futurism? Do they consider themselves a part of the same futurist tradition, or separate? The panel will discuss visions of the future from world cultures, how they are influenced by the root cultures they draw from, and how (if at all) they relate to Afrofuturism.”

- Saturday August 17, 2019, 2pm—Autographing

- Monday August 19, 2019, 10am—Kaffeeklatsch

- Monday August 19, 2019, 12:30pm—Reading

I might as well also mention that Astounding is up for the Hugo Award for Best Related Work—although the rest of the ballot is extremely formidable—and that it recently came out in paperback. (This new edition is virtually identical to the hardcover, but I took the opportunity to make a few small fixes and tweaks, and as far as I’m concerned, this is the definitive version.) And if you haven’t done so already, please check out the first three episodes of the wonderful Washington Post podcast Moonrise, which heavily draws on material from the book. Hope to see some of you soon!

Notes from all over

It’s been a while since I last posted, so I thought I’d quickly run through a few upcoming items. On Saturday June 15, the Gene Siskel Film Center in Chicago will be showing Arwen Curry’s acclaimed new documentary Worlds of Ursula K. Le Guin. After the screening, I’ll be taking part in a discussion panel with Mary Anne Mohanraj and Madhu Dubey to discuss the legacy of Le Guin, whose work increasingly seems to me like the culmination of the main line of science fiction in the United States, even if she doesn’t figure prominently in Astounding. (Which, by the way, is up for a Locus Award, the results of which will be announced at the end of this month.) The next day, on June 16, I’ll be hosting a session of my writing workshop, “Writing Fiction that Sells,” at Mary Anne’s Maram Makerspace in Oak Park. People seem to like the class, which runs from 10:00-11:45 am, and it would be great to see some of you there!

Love and Rockets

I’m delighted to share the news that Astounding is a 2019 Hugo Award Finalist for Best Related Work, along with a slate of highly deserving nominees. (The other finalists include Archive of Our Own, a project of the Organization for Transformative Works; the documentary The Hobbit Duology by Lindsay Ellis and Angelina Meehan; An Informal History of the Hugos by Jo Walton; The Mexicanx Initiative Experience at Worldcon 76 by Julia Rios, Libia Brenda, Pablo Defendini, and John Picacio; and Conversations on Writing by Ursula K. Le Guin and David Naimon. It’s a strong ballot, and I’m honored to be counted in such good company.) It feels like the high point of a journey that began with an announcement on this blog more than three years ago, and it isn’t over yet—I’m definitely going to be attending the World Science Fiction Convention in Dublin, which runs from August 15 to 19, and while I don’t know what the final outcome will be, I’m grateful to have made it even this far. The Hugos are an important part of the history that this book explores, and I’m thankful for the chance to be even a tiny piece of that story.

Outside the Wall

On Thursday, I’m heading out to the fortieth annual International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts in Orlando, Florida, where I’ll be participating in two events. One will be a reading at 8:30am featuring Jeanne Beckwith, James Patrick Kelly, Rachel Swirsky, and myself, moderated by Marco Palmieri. (I’m really looking forward to meeting Jim Kelly, who had an unforgettable story, “Monsters,” in the issue of Asimov’s Science Fiction that changed my life.) The other will be the panel “The Changing Canon of SF” at 4:15pm, moderated by James Patrick Kelly, at which Mary Anne Mohanraj, Rich Larson, and Erin Roberts will also be appearing.

In other news, I’m scheduled to speak next month at the Windy City Pulp and Paper Convention in Lombard, Illinois, where I’ll be giving a talk on Friday April 12 at 7pm. (Hugo nominations close soon, by the way, and if you’re planning to fill out a ballot, I’d be grateful if you’d consider nominating Astounding for Best Related Work.) And if you haven’t already seen it, please check out my recent review in the New York Times of John Lanchester’s dystopian novel The Wall. I should have a few more announcements here soon—please stay tuned for more!

Art and Arcana

On Sunday, I got back from the Savannah Book Festival, which was a real pleasure. My event at Trinity United Methodist Church—which was the first time that I’ve ever spoken from a pulpit—went great, at least to my eyes, and I enjoyed talking to the science fiction fans who were kind enough to turn out on a rainy afternoon. (I also had the chance to meet a number of other writers, notably Mike Witwer, whose Dungeons & Dragons: Art and Arcana looks just incredible.) During my free time, I visited the Book Lady Bookstore, which I highly recommend, and the house of Juliette Gordon Low, the founder of the Girl Scouts of the USA, much to the delight of my daughter, who recently joined the Daises. And I’m happy to note that my talk is scheduled to air on BookTV on C-SPAN2 this Saturday at 5:35pm ET, followed by an encore presentation early the following morning. (You can watch it online here.)

In the meantime, I have a few other upcoming events that might be worth mentioning. On Saturday February 23, I’ll be holding a second session of my fiction workshop, “Writing Science Fiction that Sells,” at Mary Anne Mohanraj’s makerspace in Oak Park, Illinois. The first class went better than I could have hoped, and I’d love to see some new faces there. (For the record, most of the guidelines that I plan to cover—clarity, coming up with ideas, structuring the plot as a series of objectives, managing the information that the reader receives—apply to all kinds of writing, although they present particular challenges in science fiction and fantasy.) I’m also going to be appearing with the editor and critic Gary K. Wolfe on Monday February 25 at the Blackstone branch of the Chicago Public Library, where we’ll be discussing Astounding as part of One Book, One Chicago. Please spread the word to anyone who might be interested—I hope to see some of you soon!

Sci-Fi Strawberry in Savannah

I’m heading out this morning to Savannah, Georgia for the Savannah Book Festival, where I’ll be appearing this Saturday at 4 pm at Trinity United Methodist Church to discuss Astounding. (As it happens, L. Ron Hubbard lived in Savannah for a period of time in the late forties while he was developing the mental health therapy that became known as dianetics, and I plan to briefly explore this local connection, as well as other aspects of the book that recently scored a big endorsement from a certain bearded fantasy writer.) I hope to see some of you there in person—perhaps at Leopold’s Ice Cream, which will be serving Sci-Fi Strawberry this weekend in honor of the book—and if you can’t make it, my event is scheduled to air eventually on BookTV on C-SPAN 2. And please keep an eye on this blog, where I expect to have a few other announcements soon. Stay tuned!

Visions of tomorrow

As I’ve mentioned here before, one of my few real regrets about Astounding is that I wasn’t able to devote much room to discussing the artists who played such an important role in the evolution of science fiction. (The more I think about it, the more it seems to me that their collective impact might be even greater than that of any of the writers I discuss, at least when it comes to how the genre influenced and was received by mainstream culture.) Over the last few months, I’ve done my best to address this omission, with a series of posts on such subjects as Campbell’s efforts to improve the artwork, his deliberate destruction of the covers of Unknown, and his surprising affection for the homoerotic paintings of Alejandro Cañedo. And I can reveal now that this was all in preparation for a more ambitious project that has been in the works for a while—a visual essay on the art of Astounding and Unknown that has finally appeared online in the New York Times Book Review, with the highlights scheduled to be published in the print edition this weekend. It took a lot of time and effort to put it together, especially by my editors, and I’m very proud of the result, which honors the visions of such artists as H.W. Wesso, Howard V. Brown, Hubert Rogers, Manuel Rey Isip, Frank Kelly Freas, and many others. It stands on its own, but I’ve come to think of it as an unpublished chapter from my book that deserves to be read alongside its longer companion. As I note in the article, it took years for the stories inside the magazine to catch up to the dreams of its readers, but the artwork was often remarkable from the beginning. And if you want to know what the fans of the golden age really saw when they imagined the future, the answer is right here.

The Bad Pennies, Part 3

On September 4, 1964, the annual World Science Fiction Convention opened its doors at the Hotel Leamington in Oakland, California. The guests of honor included Leigh Brackett, Edmond Hamilton, and Forrest Ackerman, with Anthony Boucher serving as toastmaster, but the conversation that weekend was dominated by a fan who wasn’t there. After a heated debate, Walter H. Breen had been banned from attendance by the convention committee, for reasons that were outlined by Bill Donaho in a special fanzine issue titled “The Great Breen Boondoggle, or All Berkeley Is Plunged into War.” (The newsletter was privately circulated, and Donaho asked that it not be quoted, but the complete text can be found online.) As Donaho makes abundantly clear, it was common knowledge among local fans that Breen—who had moved to Berkeley in the fifties—was a serial abuser of children. Four cases are described in detail, with allusions to numerous others. I won’t quote them here, but they’re horrifying, both in themselves and in the length of time over which they took place. Donaho writes:

Walter’s recent behavior has been getting many Berkeley parents not just alarmed, but semi-hysterical. If Walter is in the same room with a young boy, he never takes his eyes off the kid. He’ll be semi-abstractedly talking to someone else, but his eyes will be on the boy. And if the kid goes to the bathroom, Walter gets up and follows him in…Knowing Walter I can readily believe that he was completely oblivious to the obvious signs of strong objection. Those who say Walter is a child are right and as a child he is completely oblivious to other people’s desires and wishes unless hit on the head with them.

In the meantime, the prominent fan Alva Rogers said that he felt “great reluctance” to exclude anyone from the community, and he had a novel solution to ensure the safety of his own children whenever Breen came to visit: “He wanted to protect his kids of course, but that the situation was adequately handled at his house by having them barricade themselves in their room.”

But the most unbelievable aspect of the entire story is that no one involved seems to have disputed the facts themselves. What remained a source of controversy—both before the convention and long afterward—was the appropriate action to take, if any, against Breen. As Donaho writes of the reactions of two influential fans, with the name of a child redacted:

They swung between two points of view. “We must protect T—” and “We’re all kooks. Walter is just a little kookier than the rest of us. Where will it all end if we start rejecting people because they’re kooky?” So they swung from on the one hand proposing that if Walter wasn’t to be expelled, then the banning from individual homes should be extended so that club meetings were only held in such homes, and on the other hand calling the whole series of discussions “McCarthyite” and “Star Chamber.” “I don’t want Walter around T—, but if we do such a horrible thing as expelling him, I’ll quit fandom.”

On a more practical level, some of the organizers were concerned that if they banned Breen, they would also lose Marion Zimmer Bradley, who married him shortly before the convention began. When informed of the controversy, Breen explicitly threatened to keep Bradley away, which led to much consternation. Donaho explains: “Many of us like Marion and all this is not a very pleasant welcome to Berkeley for her. Not to mention the fact that it’s going to severely strain her relations with almost all Berkeley fans, since naturally she will defend Walter…We feel that she most probably at least knows about some of Walter’s affairs with adolescent males but believes in tolerance.”

Even after the decision was made, the wounds remained raw, and many writers and fans seemed to frame the entire incident primarily in terms of its impact on the community. In the second volume of his biography In Dialogue With His Century, William H. Patterson quotes a letter that Heinlein sent to Marion Zimmer Bradley on July 15, 1965:

The fan nuisance we were subjected to was nothing like as nasty as the horrible things that were done to you two but it was bad enough that we could get nothing else done during the weeks it went on and utterly spoiled what should have been a pleasant, happy winter. But it resulted in a decision which has made our life much pleasanter already…We have cut off all contact with organized fandom. I regret that we will miss meeting some worthwhile people in the future as the result of this decision. But the percentage of poisonous jerks in the ranks of fans makes the price too high; we’ll find our friends elsewhere.

Patterson, typically, doesn’t scrutinize this statement, moving on immediately to an unrelated story about Jerry Pournelle with the transition: “Fortunately, not all their fan interactions were were so unpleasant.” His only discussion of the incident takes the form of a footnote in which he quotes “a good short discussion” of the Breendoggle from a glossary of fan terms: “The sole point fans on both sides can agree upon is that the resulting feud had long-lasting effects [and] tore the fabric of the microcosm beyond repair…The opposing forces retired to lick their wounds and assure themselves that they had been undeniably right while the other side had been unmistakably wrong.”

By now, I hope that we can arrive at another “single point” of agreement, which is that fandom, in its effort to see itself as a place of inclusiveness for the “kooks,” disastrously failed to protect Breen’s victims. In 1991, Breen was charged with eight felony counts of child molestation and sentenced to ten years in prison—which led in turn to a comparable moment of reckoning in another subculture in which he had played an even more prominent role. Breen was renowned among coin collectors as the author of such reference works as the Complete Encyclopedia of U.S. and Colonial Coins, and the reaction within the world of numismatics was strikingly similar to what had taken place a quarter of a century earlier in Berkeley. As Charles Morgan and Hubert Walker write in an excellent article in CoinWeek:

Even in 1991, with the seeming finality of a confession and a ten-year prison sentence, it was like the sci-fi dustups of the 1960s all over again. This time, however, it was coin collectors and fans of Breen’s numismatic work that came to his defense. One such defender was fellow author John D. Wright, who wrote a letter to Coin World that stated: “My friend Walter Breen has confessed to a sin, and for this, other friends of mine have picked up stones to throw at him.” Wright criticized the American Numismatic Association for revoking Breen’s membership mere weeks after awarding him the Heath Literary Award, saying that while he did not condone Breen’s “lewd and lascivious acts,” he did not see the charge, Breen’s guilty plea or subsequent conviction as “reason for expulsion from the ANA or from any other numismatic organization.”

It’s enough to make you wonder if anything has changed in the last fifty years—but I think that it has. And the best example is the response to a more recent series of revelations about the role of Marion Zimmer Bradley. I’ll dive into this in greater detail tomorrow, in what I hope will be my final post on the subject.

The private eyes of culture

Yesterday, in my post on the late magician Ricky Jay, I neglected to mention one of the most fascinating aspects of his long career. Toward the end of his classic profile in The New Yorker, Mark Singer drops an offhand reference to an intriguing project:

Most afternoons, Jay spends a couple of hours in his office, on Sunset Boulevard, in a building owned by Andrew Solt, a television producer…He decided now to drop by the office, where he had to attend to some business involving a new venture that he has begun with Michael Weber—a consulting company called Deceptive Practices, Ltd., and offering “Arcane Knowledge on a Need to Know Basis.” They are currently working on the new Mike Nichols film, Wolf, starring Jack Nicholson.

When the article was written, Deceptive Practices was just getting off the ground, but it went on to compile an enviable list of projects, including The Illusionist, The Prestige, and most famously Forrest Gump, for which Jay and Weber designed the wheelchair that hid Gary Sinise’s legs. It isn’t clear how lucrative the business ever was, but it made for great publicity, and best of all, it allowed Jay to monetize the service that he had offered for free to the likes of David Mamet—a source of “arcane knowledge,” much of it presumably gleaned from his vast reading in the field, that wasn’t available in any other way.

As I reflected on this, I was reminded of another provider of arcane knowledge who figures prominently in one of my favorite novels. In Umberto Eco’s Foucault’s Pendulum, the narrator, Casaubon, comes home to Milan after a long sojourn abroad feeling like a man without a country. He recalls:

I decided to invent a job for myself. I knew a lot of things, unconnected things, but I wanted to be able to connect them after a few hours at a library. I once thought it was necessary to have a theory, and that my problem was that I didn’t. But nowadays all you needed was information; everybody was greedy for information, especially if it was out of date. I dropped in at the university, to see if I could fit in somewhere. The lecture halls were quiet; the students glided along the corridors like ghosts, lending one another badly made bibliographies. I knew how to make a good bibliography.

In practice, Casaubon finds that he knows a lot of things—like the identities of such obscure figures as Lord Chandos and Anselm of Canterbury—that can’t be found easily in reference books, prompting a student to marvel at him: “In your day you knew everything.” This leads Casaubon to a sudden inspiration: “I had a trade after all. I would set up a cultural investigation agency, be a kind of private eye of learning. Instead of sticking my nose into all-night dives and cathouses, I would skulk around bookshops, libraries, corridors of university departments…I was lucky enough to find two rooms and a little kitchen in an old building in the suburbs…In a pair of bookcases I arranged the atlases, encyclopedias, catalogs I acquired bit by bit.”

This feels a little like the fond daydream of a scholar like Umberto Eco himself, who spent decades acquiring arcane knowledge—not all of it required by his academic work—before becoming a famous novelist. And I suspect that many graduate students, professors, and miscellaneous bibliophiles cherish the hope that the scraps of disconnected information that they’ve accumulated over time will turn out to be useful one day, in the face of all evidence to the contrary. (Casaubon is evidently named after the character from Middlemarch who labors for years over a book titled The Key to All Mythologies, which is already completely out of date.) To illustrate what he does for a living, Casaubon offers the example of a translator who calls him one day out of the blue, desperate to know the meaning of the word “Mutakallimūn.” Casaubon asks him for two days, and then he gets to work:

I go to the library, flip through some card catalogs, give the man in the reference office a cigarette, and pick up a clue. That evening I invite an instructor in Islamic studies out for a drink. I buy him a couple of beers and he drops his guard, gives me the lowdown for nothing. I call the client back. “All right, the Mutakallimūn were radical Moslem theologians at the time of Avicenna. They said the world was a sort of dust cloud of accidents that formed particular shapes only by an instantaneous and temporary act of the divine will. If God was distracted for even a moment, the universe would fall to pieces, into a meaningless anarchy of atoms. That enough for you? The job took me three days. Pay what you think is fair.”

Eco could have picked nearly anything to serve as a case study, of course, but the story that he choses serves as a metaphor for one of the central themes of the book. If the world of information is a “meaningless anarchy of atoms,” it takes the private eyes of culture to give it shape and meaning.

All the while, however, Eco is busy undermining the pretensions of his protagonists, who pay a terrible price for treating information so lightly. And it might not seem that such brokers of arcane knowledge are even necessary these days, now that an online search generates pages of results for the Mutakallimūn. Yet there’s still a place for this kind of scholarship, which might end up being the last form of brainwork not to be made obsolete by technology. As Ricky Jay knew, by specializing deeply in one particular field, you might be able to make yourself indispensable, especially in areas where the knowledge hasn’t been written down or digitized. (In the course of researching Astounding, I was repeatedly struck by how much of the story wasn’t available in any readily accessible form. It was buried in letters, manuscripts, and other primary sources, and while this happens to be the one area where I’ve actually done some of the legwork, I have a feeling that it’s equally true of every other topic imaginable.) As both Jay and Casaubon realized, it’s a role that rests on arcane knowledge of the kind that can only be acquired by reading the books that nobody else has bothered to read in a long time, even if it doesn’t pay off right away. Casaubon tells us: “In the beginning, I had to turn a deaf ear to my conscience and write theses for desperate students. It wasn’t hard; I just went and copied some from the previous decade. But then my friends in publishing began sending me manuscripts and foreign books to read—naturally, the least appealing and for little money.” But he perseveres, and the rule that he sets for himself might still be enough, if you’re lucky, to fuel an entire career:

Still, I was accumulating experience and information, and I never threw anything away…I had a strict rule, which I think secret services follow, too: No piece of information is superior to any other. Power lies in having them all on file and then finding the connections.

Beyond the Whole Earth

Earlier this week, The New Yorker published a remarkably insightful piece by the memoirist and critic Anna Wiener on Stewart Brand, the founder of the Whole Earth Catalog. Brand, as I’ve noted here many times before, is one of my personal heroes, almost by default—I just wouldn’t be the person I am today without the books and ideas that he inspired me to discover. (The biography of Buckminster Fuller that I plan to spend the next three years writing is the result of a chain of events that started when I stumbled across a copy of the Catalog as a teenager in my local library.) And I’m far from alone. Wiener describes Brand as “a sort of human Venn diagram, celebrated for bridging the hippie counterculture and the nascent personal-computer industry,” and she observes that his work remains a touchstone to many young technologists, who admire “its irreverence toward institutions, its emphasis on autodidacticism, and its sunny view of computers as tools for personal liberation.” Even today, Wiener notes, startup founders reach out to Brand, “perhaps in search of a sense of continuity or simply out of curiosity about the industry’s origins,” which overlooks the real possibility that he might still have more meaningful insights than anybody else. Yet he also receives his share of criticism:

“The Whole Earth Catalog is well and truly obsolete and extinct,” [Brand] said. “There’s this sort of abiding interest in it, or what it was involved in, back in the day…There’s pieces being written on the East Coast about how I’m to blame for everything,” from sexism in the back-to-the-land communes to the monopolies of Google, Amazon, and Apple. “The people who are using my name as a source of good or ill things going on in cyberspace, most of them don’t know me at all.”

Wiener continues with a list of elements in the Catalog that allegedly haven’t aged well: “The pioneer rhetoric, the celebration of individualism, the disdain for government and social institutions, the elision of power structures, the hubris of youth.” She’s got a point. But when I look at that litany of qualities now, they seem less like an ideology than a survival strategy that emerged in an era with frightening similarities to our own. Brand’s vision of the world was shaped by the end of the Johnson administration and by the dawn of Nixon and Kissinger, and many Americans were perfectly right to be skeptical of institutions. His natural optimism obscured the extent to which his ideas were a reaction to the betrayals of Watergate and Vietnam, and when I look around at the world today, his insistence on the importance of individuals and small communities seems more prescient than ever. The ongoing demolition of the legacy of the progressive moment, which seems bound to continue on the judicial level no matter what happens elsewhere, only reveals how fragile it was all along. America’s withdrawal from its positions of leadership on climate change, human rights, and other issues has been so sudden and complete that I don’t think I’ll be able to take the notion of governmental reform seriously ever again. Progress imposed from the top down can always be canceled, rolled back, or reversed as soon as power changes hands. (Speaking of Roe v. Wade, Ruth Bader Ginsburg once observed: “Doctrinal limbs too swiftly shaped, experience teaches, may prove unstable.” She seems to have been right about Roe, even if it took half a century for its weaknesses to become clear, and much the same may hold true of everything that progressives have done through federal legislation.) And if the answer, as incomplete and unsatisfying as it might be, lies in greater engagement on the state and local level, the Catalog remains as useful a blueprint as any that we have.

Yet I think that Wiener’s critique is largely on the mark. The trouble with Brand’s tools, as well as their power, is that they work equally well for everyone, regardless of the underlying motive, and when detached from their original context, they can easily be twisted into a kind of libertarianism that seems callously removed from the lives of the most vulnerable. (As Brand says to Wiener: “Whole Earth Catalog was very libertarian, but that’s because it was about people in their twenties, and everybody then was reading Robert Heinlein and asserting themselves and all that stuff.”) Some of Wiener’s most perceptive comments are directed against the Clock of the Long Now, a project that has fascinated and moved me ever since it was first announced. Wiener is less impressed: “When I first heard about the ten-thousand-year clock, as it is known, it struck me as embodying the contemporary crisis of masculinity.” She points out that the clock’s backers include such problematic figures as Peter Thiel, while the funding comes largely from Jeff Bezos, whose impact on the world has yet to receive a full accounting. And after concluding her interview with Brand, Wiener writes:

As I sat on the couch in my apartment, overheating in the late-afternoon sun, I felt a growing unease that this vision for the future, however soothing, was largely fantasy. For weeks, all I had been able to feel for the future was grief. I pictured woolly mammoths roaming the charred landscape of Northern California and future archeologists discovering the remains of the ten-thousand-year clock in a swamp of nuclear waste. While antagonism between millennials and boomers is a Freudian trope, Brand’s generation will leave behind a frightening, if unintentional, inheritance. My generation, and those after us, are staring down a ravaged environment, eviscerated institutions, and the increasing erosion of democracy. In this context, the long-term view is as seductive as the apolitical, inward turn of the communards from the nineteen-sixties. What a luxury it is to be released from politics––to picture it all panning out.

Her description of this attitude as a “luxury” seems about right, and there’s no question that the Whole Earth Catalog appealed to men and women who had the privilege of reinventing themselves in their twenties, which is a form of freedom that can evolve imperceptibly into complacency and selfishness. I’ve begun to uneasily suspect that the relationship might not just be temporal, but causal. Lamenting that the Catalog failed to save us from our current predicament, which is hard to deny, can feel a little like what David Crosby once said to Rolling Stone:

Somehow Sgt. Pepper’s did not stop the Vietnam War. Somehow it didn’t work. Somebody isn’t listening. I ain’t saying stop trying; I know we’re doing the right thing to live, full on. Get it on and do it good. But the inertia we’re up against, I think everybody’s kind of underestimated it. I would’ve thought Sgt. Pepper’s could’ve stopped the war just by putting too many good vibes in the air for anybody to have a war around.

When I wrote about this quote last year, I noted that a decisive percentage of voters who were old enough to buy Sgt. Pepper on its first release ended up voting for Donald Trump, just as some fans of the Whole Earth Catalog have built companies that have come to dominate our lives in unsettling ways. And I no longer think of this as an aberration, or even as a betrayal of the values expressed by the originals, but as an exposure of the flawed idea of freedom that they represented. (Even the metaphor of the catalog itself, which implies that we can pick and choose the knowledge that we need, seems troubling now.) Writing once of Fuller’s geodesic domes, which were a fixture in the Catalog, Brand ruefully confessed that they were elegant in theory, but in practice, they “were a massive, total failure…Domes leaked, always.” Brand’s vision, which grew out of Fuller’s, remains the most compelling way of life that I know. But it leaked, always.

A Fuller Life

I’m pleased to announce that I’ve finally figured out the subject of my next book, which will be a biography of the architect and futurist Buckminster Fuller. If you’re a regular reader of this blog, you probably know how much Fuller means to me, and I’m looking forward to giving him the comprehensive portrait that he deserves. (Honestly, that’s putting it mildly. I’ve known for over a week that I’ll have a chance to tackle this project, and I still can’t quite believe that it’s really happening. And I’m especially happy that my current publisher has agreed to give me a shot at it.) At first glance, this might seem like a departure from my previous work, but it presents an opportunity to explore some of the same themes from a different angle, and to explore how they might play out in the real world. The timelines of the two projects largely coincide, with a group of subjects who were affected by the Great Depression, World War II, the Cold War, and the social upheavals of the sixties. All of them had highly personal notions about the fate of America, and Fuller used physical artifacts much as Campbell, Asimov, and Heinlein employed science fiction—to prepare their readers for survival in an era of perpetual change. Fuller’s wife, Anne, played an unsung role in his career that recalls many of the women in Astounding. Like Campbell, he approached psychology as a category of physics, and he hoped to turn the prediction of future trends into a science in itself. His skepticism of governments led him to conclude that society should be changed through design, not political institutions, and like many science fiction writers, he acted as if all disciplines could be reduced to subsets of engineering. And for most of his life, he insisted that complicated social problems could be solved through technology.

Most of his ideas were expressed through the geodesic dome, the iconic work of structural design that made him famous—and I hope that this book will be as much about the dome as about Fuller himself. It became a universal symbol of the space age, and his reputation as a futurist may have been founded largely on the fact that his most recognizable achievement instantly evoked the landscape of science fiction. From the beginning, the dome was both an elegant architectural conceit and a potent metaphor. The concept of a hemispherical shelter that used triangular elements to enclose the maximum amount of space had been explored by others, but Fuller was the first to see it as a vehicle for social change. With design principles that could be scaled up or down without limitation, it could function as a massive commercial pavilion or as a house for hippies. (Ken Kesey dreamed of building a geodesic dome to hold one of his acid tests.) It could be made out of plywood, steel, or cardboard. A dome could be cheaply assembled by hand by amateur builders, which encouraged experimentation, and its specifications could be laid out in a few pages and shared for free, like the modern blueprints for printable houses. It was a hackable, open-source machine for living that reflected a set of tools that spoke to the same men and women who were teaching themselves how to code. As I noted here recently, a teenager named Jaron Lanier, who was living in a tent with his father on an acre of desert in New Mexico, used nothing but the formulas in Lloyd Kahn’s Domebook to design and build a house that he called “Earth Station Lanier.” Lanier, who became renowned years later as the founder of virtual reality, never got over the experience. He recalled decades later: “I loved the place; dreamt about it while sleeping inside it.”

During his lifetime, Fuller was one of the most famous men in America, and he managed to become an idol to both the establishment and the counterculture. In the three decades since his death, his reputation has faded, but his legacy is visible everywhere. The influence of his geodesic structures can be seen in the Houston Astrodome, at Epcot Center, on thousands of playgrounds, in the dome tents favored by backpackers, and in the emergency shelters used after Hurricane Katrina. Fuller had a lasting impact on environmentalism and design, and his interest in unconventional forms of architecture laid the foundation for the alternative housing movement. His homegrown system of geometry led to insights into the biological structure of viruses and the logic of communications networks, and after he died, he was honored by the discoverers of a revolutionary form of carbon that resembled a geodesic sphere, which became known as fullerene, or the buckyball. And I’m particularly intrigued by his parallels to the later generation of startup founders. During the seventies, he was a hero to the likes of Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs, who later featured him prominently in the first “Think Different” commercial, and he was the prototype of the Silicon Valley types who followed. He was a Harvard dropout who had been passed over by the college’s exclusive social clubs, and despite his lack of formal training, he turned himself into an entrepreneur who believed in changing society through innovative products and environmental design. Fuller wore the same outfit to all his public appearances, and his personal habits amounted to an early form of biohacking. (Fuller slept each day for just a few hours, taking a nap whenever he felt tired, and survived mostly on steak and tea.) His closest equivalent today may well be Elon Musk, which tells us a lot about both men.

And this project is personally significant to me. I first encountered Fuller through The Whole Earth Catalog, which opened its first edition with two pages dedicated to his work, preceded by a statement from editor Stewart Brand: “The insights of Buckminster Fuller initiated this catalog.” I was three years old when he died, and I grew up in the shadow of his influence in the Bay Area. The week before my freshman year in high school, I bought a used copy of his book Critical Path, and I tried unsuccessfully to plow through Synergetics. (At the time, this all felt kind of normal, and it’s only when I look back that it seems strange—which tells you a lot about me, too.) Above all else, I was drawn to his reputation as the ultimate generalist, which reflected my idea of what my life should be, and I’m hugely excited by the prospect of returning to him now. Fuller has been the subject of countless other works, but never a truly authoritative biography, which is a project that meets both Susan Sontag’s admonition that a writer should try to be useful and the test that I stole from Lin-Manuel Miranda: “What’s the thing that’s not in the world that should be in the world?” Best of all, the process looks to be tremendously interesting for its own sake—I think it’s going to rewire my brain. It also requires an unbelievable amount of research. To apply the same balanced, fully sourced, narrative approach to his life that I tried to take for Campbell, I’ll need to work through all of Fuller’s published work, a mountain of primary sources, and what might literally be the largest single archive for any private individual in history. I know from experience that I can’t do it alone, and I’m looking forward to seeking help from the same kind of brain trust that I was lucky to have for Astounding. Those of you who have stuck with this blog should be prepared to hear a lot more about Fuller over the next three years, but I wouldn’t be doing this at all if I didn’t think that you might find it interesting. And who knows? He might change your life, too.