Posts Tagged ‘Reddit’

Running it up the flagpole

Two months ago, I was browsing Reddit when I stumbled across a post that said: “TIL that the current American Flag design originated as a school project from Robert G Heft, who received a B- for lack of originality, yet was promised an A if he successfully got it selected as the national flag. The design was later chosen by President Eisenhower for the national flag of the US.” After I read the submission, which received more than 21,000 upvotes, I was skeptical enough of the story to dig deeper. The result is my article “False Flag,” which appeared today in Slate. I won’t spoil it here, but rest assured that it’s a wild ride, complete with excursions into newspaper archives, government documents, and the world of vexillology, or flag studies. It’s probably my most surprising discovery in a lifetime of looking into unlikely subjects, and I have a hunch that there might be even more to come. I hope you’ll check it out.

Do media brands have a future?

Note: I’m taking a break for the next few days, so I’ll be republishing some of my favorite posts from earlier in this blog’s run. This post originally appeared, in a slightly different form, on March 24, 2015.

Years ago, my online browsing habits followed a predictable routine. Each morning, after checking my email, I’d click over to read the headlines on the New York Times, then The A.V. Club, followed by whatever blogger, probably Andrew Sullivan, I was following at the moment. Although I didn’t think of it in those terms, in each case, I was responding to a brand: I trusted these sites to provide me with a few minutes of engaging content, and although I didn’t know exactly what would be posted each day, there were certain intangibles—a voice, a writer’s point of view, a stamp of quality—that assured me that a visit there would be worth my time. These days, my regimen looks very different. I still tune into the New York Times and The A.V. Club for old time’s sake, but the bulk of my browsing is done through Reddit or Digg. I don’t visit a lot of sites specifically for the content they provide; instead, I trust in aggregators, whether crowdsourced by upvotes or curated more deliberately, to direct my attention to whatever is worth reading from one hour to the next. In many cases, when I click through to a story, I don’t even know where the link goes, and I’ve lost count of the times I’ve told my wife about an article I saw “somewhere on Digg.” And once I’m done with that one spotlighted piece, I’m not particularly likely to visit the site later to see what else it might have to offer.

As a content provider—which is a term I hate—in my own right, the pattern of consumption that I see in myself chills me to the bone. Yet it represents a rational, if subconscious, choice. I’m simply betting that I’ll have a better time by trusting the aggregators, which admittedly are brands in themselves, rather than the brand of a specific writer or publication. Individual authors or sites can be erratic; on slow news days, even the Times can seem like a bore. But an aggregator that sweeps the entire web for material will always come up with something diverting, and I’m not tied down to any one source. After all, even the most consistently reliable reads can lose interest over time. I started visiting Reddit more regularly during the last presidential election, for instance, after I got tired of Andrew Sullivan’s increasingly panicky and hysterical tone: reading his blog turned into a chore. And I became less active on The A.V. Club, particularly as a commenter, after much of its core staff decamped for The Dissolve and Vox, although I still read certain features faithfully. To be honest, it’s been years since a new site grabbed my attention to the point where I wanted to read it every day. And I’m not alone: the problem of retaining loyalty to brands is the single greatest challenge confronting journalism of all kinds, even as musical artists deal with much the same issues on Spotify and Pandora.

Faced with a future driven by aggregators, which destroy the old business models for distributing content, most media companies have turned to one of two solutions. Either you provide content in a form that resists aggregation while still attracting an audience, or you nurture a voice or personality compelling enough to draw readers back on a regular basis. Both have their problems. At first glance, the two kinds of content that might seem immune to aggregation are television shows and podcasts, but that’s more of a structural quirk. From a network’s perspective, the real brand at stake isn’t Community or Parks and Recreation but NBC itself, and with the proliferation of viewing and streaming options, we’re much less likely to tune in to whatever the network wants to show us on Thursday night. And podcasts are simply awaiting the appearance of a reliable aggregator that will cull the day’s best episodes, or, even more likely, the best two- or three-minute snippets. Once that happens, we’re likely to start listening to podcasts as we consume written content, as a kind of smorgasbord of diversion that isn’t tied down to any one creator. As for personalities, they’re great when you can get them, but they’re excruciatingly rare. Talk radio is a fantastic example: the fact that maybe half a dozen guys—and they’re mostly men—have divided the radio audience between them for decades now points to how few can really do it.

And there’s no reason to expect other kinds of content to be any different. Every author hopes that his voice will be distinctive enough to draw in people who simply want to hear everything he says, but there aren’t many such writers left: David Carr, who passed away over a year ago, was one of the last. Even I’m mostly reconciled to the fact that readership on this blog is largely dependent on factors outside my control. My single busiest day occurred after one of my posts appeared on the front page of Reddit, but as I’ve noted elsewhere, after a heady period in which a mass of eyeballs equivalent to the population of Cincinnati came to visit, few, if any, stuck around to read more. I’ve slowly acquired a coterie of regular readers, but page views have remained more or less fixed for a long time, and my only spikes in traffic come when a post is linked somewhere else. I do what I can to keep the level of quality consistent, and if nothing else, I don’t lack for productivity. All I can really do is keep writing, throw out ideas, and hope that a few of them stick, which isn’t all that different from what the major media companies are doing on a much larger scale. (Although you can find lessons in unexpected places. One brand that caught my eye—in the form of a shelf of musty books, most of them long out of print—was the Bollingen Foundation, which I still think is a fascinating, if not entirely useful, counterexample.) But I can’t help but feel that there must be a better way.

The magic xylophone

Earlier this morning, I was browsing online when I noticed that Mark Kirkland, a longtime director for The Simpsons, was answering questions on Reddit. I was immediately excited, both because Kirkland directed such legendary installments as “Last Exit to Springfield”—often considered the best episode that the series ever did—and “Homer’s Barbershop Quartet,” and because he’s a reliably funny and smart presence on the show’s commentary tracks. When I clicked on the page, however, I found that the top-ranked question was something that I probably should have expected:

In episode 2F09 when Itchy plays Scratchy’s skeleton like a xylophone, he strikes the same rib twice in succession, yet he produces two clearly different tones. I mean, what are we to believe, that this is some sort of a magic xylophone or something? Boy, I really hope somebody got fired for that blunder.

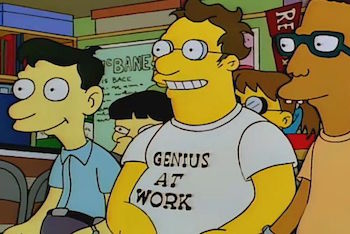

For those who are lucky enough not to get the joke, this is a reference to the episode “The Itchy & Scratchy & Poochie Show,” in which Homer takes similar questions from a roomful of nerds. Homer responds: “I’ll field that one. Let me ask you a question. Why would a grown man whose shirt says ‘Genius at Work’ spend all his time watching a children’s cartoon show?” To which the nerd replies: “I withdraw my question.”

Even within the vast universe of repurposed Simpsons quotes, which I’ve elsewhere compared to a complete metaphorical language, this is about as canonical as it gets: it’s a reference that must get rehashed online somewhere every few minutes, usually in discussions about some absurdly nitpicky aspect of a movie or television show. If Kirkland had simply responded with the expected quote from Homer, the commenters would have expressed their approval and moved on. But Kirkland didn’t seem to recognize the reference, and he replied with a straight face, leading to a minor explosion of indignation in the comments that followed. Redditors simply couldn’t believe that Kirkland didn’t know the joke, and many held it against him personally. As one wrote: “I honestly don’t think he got the reference. If I’m right, I think it explains a lot about the quality of The Simpsons these days.” Another replied: “Sadly true.” To their credit, a few other commenters responded with the obvious rejoinders. Kirkland has spent the last three decades working on new episodes of the series; it isn’t fair to expect him to immediately recognize a line that aired almost twenty years ago from a script that he didn’t even direct; and fans who have watched every episode from the show’s golden years a dozen times and quoted them repeatedly to one another are operating in a different frame of reference than the creative staff. (Anecdotal evidence certainly bears this out: the fans have consistently trounced the writers in trivia contests. As onetime show runner David Mirkin once said in their defense: “We’re too busy creating the new stuff.”)

And yet the whole exchange still rankled me, to the point where I feel obliged to write about it here. There’s one big point that ought to be italicized for emphasis: the commenters who quoted an episode word for word, and then became upset when one of the show’s most valuable contributors failed to give them the automatic reply they wanted, are unconsciously embodying the very thing that the original joke was mocking. “The Itchy & Scratchy & Poochie Show” remains one of the show’s most fascinating episodes, and its relevance has only increased as the years have gone by. Its writer, David X. Cohen, conceived it as a commentary on a show that he honestly believed was nearing the end of its run, and even if he was off by a few decades, its jokes about fans and their relationship to a favorite series are still funny and accurate. What he couldn’t have anticipated was how the compounding effect of time would make the satire almost too mild. This is the episode, after all, that includes both the lines quoted above and this equally famous—and prescient—exchange:

Comic Book Guy: Last night’s Itchy & Scratchy was, without a doubt, the worst episode ever. Rest assured that I was on the Internet within minutes registering my disgust throughout the world.

Bart: Hey, I know it wasn’t great, but what right do you have to complain?

Comic Book Guy: As a loyal viewer, I feel they owe me.

Bart: What? They’ve given you thousands of hours of entertainment for free. What could they possibly owe you? I mean, if anything, you owe them.

Comic Book Guy (after a pause): Worst episode ever.

Cohen may have intended this as a humorous exaggeration, but it was really a glimpse of the show’s future, and Reddit’s exchange with Kirkland is just a particularly stark example. This isn’t the place to go yet again into the reasons for the show’s decline in quality over the last fifteen years, except to state that the problem almost certainly isn’t that the writers and directors have failed to memorize the old episodes and constantly quote them to one another. If anything, the show has suffered from being too much of an echo chamber, leading to a reliance on throwaway lines and easy gags over coherent stories—which argues that the series should be turned less inward on itself, not more. But it reminds us of one of the show’s underlying problems: as vocal as its fans are, they don’t seem to know what they want from it. (As the leader of an audience focus group says in the very same episode: “So you want a realistic down-to-earth show that’s completely off the wall and swarming with magic robots?”) At this late date, it seems safe to say that The Simpsons is what it is, and that any given fan’s relationship with the show is something that he’ll have to work out for himself. But a decent first step to any kind of understanding would be to watch “The Itchy & Scratchy & Poochie Show” once more, and, instead of mindlessly parroting its lines, to take a good look at it and ask which character reminds us the most of ourselves. Because the magic xylophone tolls for thee.

The prepositional phase

A few days ago, a seemingly innocent question was posted to the Explain Like I’m Five forum on Reddit: “Why do we say someone was ‘in’ a movie, but ‘on’ a TV show?” This may not seem like a mindblower, but it’s something I’ve wanted to write about here for a long time, and I find myself thinking about it at least a couple of times a week. In particular, it occurs to me whenever I type up a descriptive tag for an image on this blog, which is often a screenshot of an actor in a movie or on a television show. When you’re doing the kind of routine housekeeping, your thoughts tend to wander in odd directions, and I’ve consistently found myself wondering why I need to type “Jon Hamm on Mad Men” on the one hand and “Matthew McConaughey in Interstellar” on the other. And while prepositions in any living language are inherently weird and inexplicable—as a few spoilsport commenters on the thread above take pains to point out—I think it’s still worth digging into the problem, since it seems to express something meaningful about the way we experience these two different but entwined forms of storytelling.

As usual, the discussion on Reddit involves a lot of wild guesswork and speculation, but it settles around a number of intriguing points:

- A television set is perceived as an object, while a movie is a collection of information. Saying that someone is “on television” is rooted in our experience of that piece of furniture in our living room on which stories are projected—hence the usage “What’s on?” A theatrical feature, by contrast, has an inherent intangibility, as a series of flickering images appearing at a distance: it’s less a physical thing than an event.

- Conversely, you could also think of a television show as an ongoing process, while a movie has a fixed beginning or end. Thus it seems intuitively correct to think of an actor as “on” a television show, as if he were a passenger on a journey with no obvious destination, while the same actor resides “in” the clearly defined container that a movie provides.

And while there are additional nuances involved here—can we say an actor was “in” a show that is no longer on the air?—it seems that these prepositions hinge on paradoxical properties of physicality and duration. A television show is a physical object with no endpoint; a movie is an intangible idea with definite boundaries.

If we follow this logic further, it sheds light on a number of problems of real practical resonance. There’s the issue, for instance, of why television stars have often encountered trouble finding the same success in film. Critics like to note that there’s a difference between the kind of personality we want to invite into our homes night after night and the kind we want to pay money to see in a theater. A face that resides comfortably in a physical box may not look nearly as appealing on a screen the size of a billboard: television actors tend to have faces, however attractive, that can fade into the background, while actors in feature films demand our attention. Similarly, a television show can—and often does—survive once its original lead has moved on, while nearly every mainstream movie is built explicitly around a star. Saying that an actor is “on” a show implies, rightly or not, that he could disembark while the series as a whole sailed on; try to remove an actor “in” a movie, though, and you’re talking about a fundamental disruption of the narrative fabric. It’s possible to take this kind of analogy too far, of course, and there are plenty of exceptions. But it’s hard not to regard those unassuming prepositions as signaling something deeper about how we relate to the fictional men and women in our lives.

Which raises the unanswerable question of how these linguistic conventions might be different if movies and television had somehow emerged together in their current form. (We can leave aside the related conundrum of why we “see” a movie in theaters but “watch” it everywhere else.) Neither film nor television is particularly tethered to any one device or delivery system these days: if anything, movies have gotten slightly more tangible, television harder to pin down. And while many shows have started to feel more like finite works of art, studio franchises resist tidy endings: it makes about as much sense to say that Matthew McConaughey was “in” True Detective as to say that Vin Diesel is “on” the Fast and Furious series. And while the line between these usages may continue to blur, to the point where our children may use them interchangeably, it seems likely that those propositions will persist for a while longer, much like the ideas underneath. A fossil word can live on in a language long after its original purpose has been forgotten, and old assumptions about media—like the premise that television is somehow a less reputable or prestigious medium than film, despite huge evidence to the contrary—also have a way of lingering on. And it can take a long time before we learn how to think, or speak, outside the box.

Do media brands have a future?

Years ago, my online browsing habits followed a predictable routine. Each morning, after checking my email, I’d click over to read the headlines on the New York Times, then The A.V. Club, followed by whatever blogger, probably Andrew Sullivan, I was following at the moment. Although I didn’t think of it in those terms, in each case, I was responding to a brand: I trusted these sites to provide me with a few minutes of engaging content, and although I didn’t know exactly what would be posted each day, there were certain intangibles—a voice, a writer’s point of view, a stamp of quality—that assured me that a visit there would be worth my time. These days, my regimen looks very different. I still tune into the New York Times and The A.V. Club for old time’s sake, but the bulk of my browsing is done through Reddit or Digg. I don’t visit a lot of sites specifically for the content they provide; instead, I trust in aggregators, whether crowdsourced by upvotes or curated more deliberately, to direct my attention to whatever is worth reading from one hour to the next. In many cases, when I click through to a story, I don’t even know where the link goes, and I’ve lost count of the times I’ve told my wife about an article I saw “somewhere on Digg.” And once I’m done with that one spotlighted piece, I’m not particularly likely to visit the site later to see what else it might have to offer.

As a content provider—which is a term I hate—in my own right, the pattern of consumption that I see in myself chills me to the bone. Yet it represents a rational, if subconscious, choice. I’m simply betting that I’ll have a better time by trusting the aggregators, which admittedly are brands in themselves, rather than the brand of a specific writer or publication. Individual authors or sites can be erratic; on slow news days, even the Times can seem like a bore. But an aggregator that sweeps the entire web for material will always come up with something diverting, and I’m not tied down to any one site. After all, even the most consistently reliable reads can lose interest over time. I started visiting Reddit more regularly during the last presidential election, for instance, after I got tired of Andrew Sullivan’s increasingly panicky and hysterical tone: reading his blog turned into a chore. And I became less active on The A.V. Club, particularly as a commenter, after much of its core staff decamped for The Dissolve and Vox, although I still read certain features faithfully. To be honest, it’s been years since a new site grabbed my attention to the point where I wanted to read it every day. And I’m not alone: the problem of retaining loyalty to brands is the single greatest challenge confronting journalism of all kinds, even as musical artists deal with much the same issues on Spotify and Pandora.

Faced with a future driven by aggregators, which destroy the old business models for distributing content, most media companies have turned to one of two solutions. Either you provide content in a form that resists aggregation while still attracting an audience, or you nurture a voice or personality compelling enough to draw readers back on a regular basis. Both have their problems. At first glance, the two kinds of content that might seem immune to aggregation are television shows and podcasts, but that’s more of a structural quirk. From a network’s perspective, the real brand at stake isn’t Community or Parks and Recreation but NBC itself, and with the proliferation of viewing and streaming options, we’re much less likely to tune in to whatever the network wants to show us on Thursday night. And podcasts are simply awaiting the appearance of a reliable aggregator that will cull the day’s best episodes, or, even more likely, the best two- or three-minute snippets. Once that happens, we’re likely to start listening to podcasts as we consume written content, as a kind of smorgasbord of diversion that isn’t tied down to any one creator. As for personalities, they’re great when you can get them, but they’re excruciatingly rare. Talk radio is a fantastic example: the fact that maybe half a dozen guys—and they’re mostly men—have divided the radio audience between them for decades now points to how few can really do it.

And there’s no reason to expect other kinds of content to be any different. Every author hopes that his voice will be distinctive enough to draw in people who simply want to hear everything he says, but there aren’t many such writers left. (David Carr, who passed away earlier this year, was one of the last.) Even I’m mostly reconciled to the fact that readership on this blog is largely dependent on factors outside my control. My single busiest day occurred after one of my posts appeared on the front page of Reddit, but as I’ve noted elsewhere, after a heady period in which a mass of eyeballs equivalent to the population of Cincinnati came to visit, few, if any, stuck around to read more. I’ve slowly acquired a coterie of regular readers, but page views have remained more or less fixed for a long time, and my only spikes in traffic come when a post is linked somewhere else. I do what I can to keep the level of quality consistent, and if nothing else, I don’t lack for productivity. All I can really do is keep writing, throw out ideas, and hope that a few of them stick, which isn’t all that different from what the major media companies are doing on a much larger scale. But I can’t help but feel that there must be a better way. Tomorrow, I’m going to talk more about one brand that caught my eye—in the form of a shelf of musty books by the Bollingen Foundation, most of them long out of print—to see if its example holds any lessons for the rest of us.

The Reddit Wedding

Early last Sunday, after giving my daughter a bottle, putting on the kettle for coffee, and glancing over the front page of the New York Times, I moved on to the next stop in my morning routine: I went to Reddit. Like many of us, I’ve started to think of Reddit as a convenient curator of whatever happens to be taking place online that day, and after customizing the landing page to my tastes—unsubscribing from the meme factories, keeping the discussions of news and politics well out of view—it has gradually turned into the site where I spend most of my time. (It’s also started to leave a mark on my home life: I have a bad habit of starting conversations with my wife with “There was a funny thread on Reddit today…) That morning, I was looking over the top posts when I noticed a link to an article about the author George R.R. Martin and his use of the antiquated word processor WordStar to write all of his fiction, including A Song of Ice and Fire, aka Game of Thrones. At first, I was amused, because I’d once thought about submitting that very tidbit myself. A second later, I realized why the post looked so familiar. It was linked to this blog.

At that point, my first thought, and I’m not kidding, was, “Hey, I wonder if I’ll get a spike in traffic.” And I did. In fact, if you’re curious about what it means to end up on the front page of Reddit, as of this writing, that post—which represented about an hour’s work from almost a year ago—has racked up close to 300,000 hits, more than doubling the lifetime page views for this entire blog. At its peak, it was the third most highly ranked post on Reddit that morning, a position it held very briefly: within a few hours, it had dropped off the front page entirely, although not before inspiring well over 1,500 comments. Most of the discussion revolved around WordStar, the merits of different word processing platforms, and about eighty variations on the joke of “Oh, so that’s why it’s taking Martin so long to finish.” The source of the piece was mentioned maybe once or twice, and several commenters seemed to think that this was Martin’s blog. And the net impact on this site itself, after the initial flurry of interest, was minimal. A few days later, traffic has fallen to its usual modest numbers, and only a handful of new arrivals seem to have stuck around. (If you’re one of them, I thank you.) And it’s likely that none of this site’s regular readers noticed that anything out of the ordinary was happening at all.

In short, because of one random link, this blog received an influx of visitors equivalent to the population of Cincinnati, and not a trace remains—I might as well have dreamed it. But then again, this isn’t surprising, given how most people, including me, tend to browse content these days. When I see an interesting link on Reddit, I’ll click on it, skim the text, then head back to the post for the comments. (For a lot of articles, particularly on science, I’ll read the comments first to make sure the headline wasn’t misleading.) I’ll rarely, if ever, pause to see what else the destination site has to offer; it’s just too easy to go back to Reddit or Digg or Twitter to find the next interesting article from somewhere else. In other words, I’m just one of the many guilty parties in what has been dubbed the death of the homepage. The New York Times landing page has lost eighty million visitors over the last two years, and it isn’t hard to see why. We’re still reading the Times, but we’re following links from elsewhere, which not only changes the way we read news, but the news we’re likely to read: less hard reporting, more quizzes, infographics, entertainment and self-help items, as well as the occasional diverting item from a site like this.

And it’s a reality that writers and publishers, including homegrown operations like mine, need to confront. The migration of content away from homepages and into social media isn’t necessarily a bad thing; comments on Reddit, for instance, are almost invariably more capably ranked and moderated, more active, and more interesting than the wasteland of comments on even major news sites. (Personally, I’d be fine if most newspapers dropped commenting altogether, as Scientific American and the Chicago Sun-Times recently did, and left the discussion to take place wherever the story gets picked up.) But it also means that we need to start thinking of readers less as a proprietary asset retained over time than as something we have to win all over again with every post, while getting used to the fact that none of it will last. Or almost none of it. A few days after my post appeared on Reddit, George R.R. Martin was interviewed by Conan O’Brien, who asked him about his use of WordStar—leading to another burst of coverage, even though Martin’s preferences in word processing have long been a matter of record. And while I can’t say for sure, between you and me, I’m almost positive that it wouldn’t have come up if someone on Conan’s staff hadn’t seen my post. It isn’t much. But it’s nice.

That old book smell

Lignin, the stuff that prevents all trees from adopting the weeping habit, is a polymer made up of units that are closely related to vanillin. When made into paper and stored for years, it breaks down and smells good. Which is how divine providence has arranged for secondhand bookstores to smell like good quality vanilla absolute, subliminally stoking a hunger for knowledge in all of us.

—Luca Turin and Tania Sanchez, Perfumes: The Guide (courtesy of Reddit)

Quote of the Day

Question: Can we inspire more kids to pursue space-related science and research? If so, how?

Answer: Kids are never the problem. They are born scientists. The problem is always the adults.