Archive for August 9th, 2017

Thinking on your feet

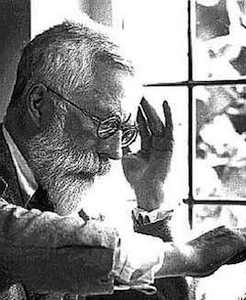

The director Elia Kazan, whose credits included A Streetcar Named Desire and On the Waterfront, was proud of his legs. In his memoirs, which the editor Robert Gottlieb calls “the most gripping and revealing book I know about the theater and Hollywood,” Kazan writes of his childhood:

Everything I wanted most I would have to obtain secretly. I learned to conceal my feelings and to work to fulfill them surreptitiously…What I wanted most I’d have to take—quietly and quickly—from others. Not a logical step, but I made it at a leap. I learned to mask my desires, hide my truest feeling; I trained myself to live in deprivation, in silence, never complaining, never begging, in isolation, without expecting kindness or favors or even good luck…I worked waxing floors—forty cents an hour. I worked at a small truck farm across the road—fifty cents an hour. I caddied every afternoon I could at the Wykagyl Country Club, carrying the bags of middle-aged women in long woolen skirts—a dollar a round. I spent nothing. I didn’t take trolleys; I walked. Everywhere. I have strong leg muscles from that time.

The italics are mine, but Kazan emphasized his legs often enough on his own. In an address that he delivered at a retrospective at Wesleyan University in 1973, long after his career had peaked, he told the audience: “Ask me how with all that knowledge and all that wisdom, and all that training and all those capabilities, including the strong legs of a major league outfielder, how did I manage to mess up some of the films I’ve directed so badly?”

As he grew older, Kazan’s feelings about his legs became inseparable from his thoughts on his own physical decline. In an essay titled “The Pleasures of Directing,” which, like the address quoted above, can be found in the excellent book Kazan on Directing, Kazan observes sadly: “They’ve all said it. ‘Directing is a young man’s game.’ And time passing proves them right.” He continues:

What goes first? With an athlete, the legs go first. A director stands all day, even when he’s provided with chairs, jeeps, and limos. He walks over to an actor, stands alongside and talks to him; with a star he may kneel at the side of the chair where his treasure sits. The legs do get weary. Mine have. I didn’t think it would happen because I’ve taken care of my body, always exercised. But I suddenly found I don’t want to play singles. Doubles, okay. I stand at the net when my partner serves, and I don’t have to cover as much ground. But even at that…

I notice also that I want a shorter game—that is to say also, shorter workdays, which is the point. In conventional directing, the time of day when the director has to be most able, most prepared to push the actors hard and get what he needs, usually the close-ups of the so-called “master scene,” is in the afternoon. A director can’t afford to be tired in the late afternoon. That is also the time—after the thoughtful quiet of lunch—when he must correct what has not gone well in the morning. He better be prepared, he better be good.

As far as artistic advice goes, this is as close to the real thing as it gets. But it can only occur to an artist who can no longer take for granted the energy on which he has unthinkingly relied for most of his life.

Kazan isn’t the only player in the film industry to draw a connection between physical strength—or at least stamina—and the medium’s artistic demands. Guy Hamilton, who directed Goldfinger, once said: “To be a director, all you need is a hide like a rhinoceros—and strong legs, and the ability to think on your feet…Talent is something else.” None other than Christopher Nolan believes so much in the importance of standing that he’s institutionalized it on his film sets, as Mark Rylance recently told The Independent: “He does things like he doesn’t like having chairs on set for actors or bottles of water, he’s very particular…[It] keeps you on your toes, literally.” Walter Murch, meanwhile, noted that a film editor needed “a strong back and arms” to lug around reels of celluloid, which is less of a concern in the days of digital editing, but still worth bearing in mind. Murch famously likes to stand while editing, like a surgeon in the operating room:

Editing is sort of a strange combination of being a brain surgeon and a short-order cook. You’ll never see those guys sitting down on the job. The more you engage your entire body in the process of editing, the better and more balletic the flow of images will be. I might be sitting when I’m reviewing material, but when I’m choosing the point to cut out of a shot, I will always jump out of the chair. A gunfighter will always stand, because it’s the fastest, most accurate way to get to his gun. Imagine High Noon with Gary Cooper sitting in a chair. I feel the fastest, most accurate way to choose the critically important frame I will cut out of a shot is to be standing. I have kind of a gunfighter’s stance.

And as Murch suggests, this applies as much to solitary craftsmen as it does to the social and physical world of the director. Philip Roth, who worked at a lectern, claimed that he paced half a mile for every page that he wrote, while the mathematician Robert P. Langlands reflected: “[My] many hours of physical effort as a youth also meant that my body, never frail but also initially not particularly strong, has lasted much longer than a sedentary occupation might have otherwise permitted.” Standing and walking can be a proxy for mental and moral acuity, as Bertrand Russell implied so memorably:

Our mental makeup is suited to a life of very severe physical labor. I used, when I was younger, to take my holidays walking. I would cover twenty-five miles a day, and when the evening came I had no need of anything to keep me from boredom, since the delight of sitting amply sufficed. But modern life cannot be conducted on these physically strenuous principles. A great deal of work is sedentary, and most manual work exercises only a few specialized muscles. When crowds assemble in Trafalgar Square to cheer to the echo an announcement that the government has decided to have them killed, they would not do so if they had all walked twenty-five miles that day.

Such energy, as Kazan reminds us, isn’t limitless. I still think of myself as relatively young, but I don’t have the raw mental or physical resources that I did fifteen years ago, and I’ve had to come up with various tricks—what a pickup basketball player might call “old-man shit”—to maintain my old levels of productivity. I’ve written elsewhere that certain kinds of thinking are best done sitting down, but there’s also a case to be made for thinking on your feet. Standing is the original power pose, and perhaps the only one likely to have any real effects. And it’s in the late afternoons, both of a working day and of an entire life, that you need to stand and deliver.

Quote of the Day

Experimental observations are only experience carefully planned in advance.