Archive for November 21st, 2018

Beyond the Whole Earth

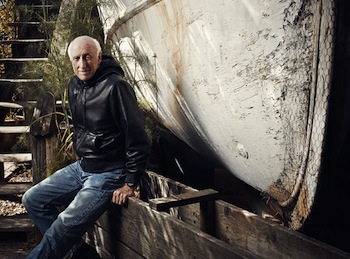

Earlier this week, The New Yorker published a remarkably insightful piece by the memoirist and critic Anna Wiener on Stewart Brand, the founder of the Whole Earth Catalog. Brand, as I’ve noted here many times before, is one of my personal heroes, almost by default—I just wouldn’t be the person I am today without the books and ideas that he inspired me to discover. (The biography of Buckminster Fuller that I plan to spend the next three years writing is the result of a chain of events that started when I stumbled across a copy of the Catalog as a teenager in my local library.) And I’m far from alone. Wiener describes Brand as “a sort of human Venn diagram, celebrated for bridging the hippie counterculture and the nascent personal-computer industry,” and she observes that his work remains a touchstone to many young technologists, who admire “its irreverence toward institutions, its emphasis on autodidacticism, and its sunny view of computers as tools for personal liberation.” Even today, Wiener notes, startup founders reach out to Brand, “perhaps in search of a sense of continuity or simply out of curiosity about the industry’s origins,” which overlooks the real possibility that he might still have more meaningful insights than anybody else. Yet he also receives his share of criticism:

“The Whole Earth Catalog is well and truly obsolete and extinct,” [Brand] said. “There’s this sort of abiding interest in it, or what it was involved in, back in the day…There’s pieces being written on the East Coast about how I’m to blame for everything,” from sexism in the back-to-the-land communes to the monopolies of Google, Amazon, and Apple. “The people who are using my name as a source of good or ill things going on in cyberspace, most of them don’t know me at all.”

Wiener continues with a list of elements in the Catalog that allegedly haven’t aged well: “The pioneer rhetoric, the celebration of individualism, the disdain for government and social institutions, the elision of power structures, the hubris of youth.” She’s got a point. But when I look at that litany of qualities now, they seem less like an ideology than a survival strategy that emerged in an era with frightening similarities to our own. Brand’s vision of the world was shaped by the end of the Johnson administration and by the dawn of Nixon and Kissinger, and many Americans were perfectly right to be skeptical of institutions. His natural optimism obscured the extent to which his ideas were a reaction to the betrayals of Watergate and Vietnam, and when I look around at the world today, his insistence on the importance of individuals and small communities seems more prescient than ever. The ongoing demolition of the legacy of the progressive moment, which seems bound to continue on the judicial level no matter what happens elsewhere, only reveals how fragile it was all along. America’s withdrawal from its positions of leadership on climate change, human rights, and other issues has been so sudden and complete that I don’t think I’ll be able to take the notion of governmental reform seriously ever again. Progress imposed from the top down can always be canceled, rolled back, or reversed as soon as power changes hands. (Speaking of Roe v. Wade, Ruth Bader Ginsburg once observed: “Doctrinal limbs too swiftly shaped, experience teaches, may prove unstable.” She seems to have been right about Roe, even if it took half a century for its weaknesses to become clear, and much the same may hold true of everything that progressives have done through federal legislation.) And if the answer, as incomplete and unsatisfying as it might be, lies in greater engagement on the state and local level, the Catalog remains as useful a blueprint as any that we have.

Yet I think that Wiener’s critique is largely on the mark. The trouble with Brand’s tools, as well as their power, is that they work equally well for everyone, regardless of the underlying motive, and when detached from their original context, they can easily be twisted into a kind of libertarianism that seems callously removed from the lives of the most vulnerable. (As Brand says to Wiener: “Whole Earth Catalog was very libertarian, but that’s because it was about people in their twenties, and everybody then was reading Robert Heinlein and asserting themselves and all that stuff.”) Some of Wiener’s most perceptive comments are directed against the Clock of the Long Now, a project that has fascinated and moved me ever since it was first announced. Wiener is less impressed: “When I first heard about the ten-thousand-year clock, as it is known, it struck me as embodying the contemporary crisis of masculinity.” She points out that the clock’s backers include such problematic figures as Peter Thiel, while the funding comes largely from Jeff Bezos, whose impact on the world has yet to receive a full accounting. And after concluding her interview with Brand, Wiener writes:

As I sat on the couch in my apartment, overheating in the late-afternoon sun, I felt a growing unease that this vision for the future, however soothing, was largely fantasy. For weeks, all I had been able to feel for the future was grief. I pictured woolly mammoths roaming the charred landscape of Northern California and future archeologists discovering the remains of the ten-thousand-year clock in a swamp of nuclear waste. While antagonism between millennials and boomers is a Freudian trope, Brand’s generation will leave behind a frightening, if unintentional, inheritance. My generation, and those after us, are staring down a ravaged environment, eviscerated institutions, and the increasing erosion of democracy. In this context, the long-term view is as seductive as the apolitical, inward turn of the communards from the nineteen-sixties. What a luxury it is to be released from politics––to picture it all panning out.

Her description of this attitude as a “luxury” seems about right, and there’s no question that the Whole Earth Catalog appealed to men and women who had the privilege of reinventing themselves in their twenties, which is a form of freedom that can evolve imperceptibly into complacency and selfishness. I’ve begun to uneasily suspect that the relationship might not just be temporal, but causal. Lamenting that the Catalog failed to save us from our current predicament, which is hard to deny, can feel a little like what David Crosby once said to Rolling Stone:

Somehow Sgt. Pepper’s did not stop the Vietnam War. Somehow it didn’t work. Somebody isn’t listening. I ain’t saying stop trying; I know we’re doing the right thing to live, full on. Get it on and do it good. But the inertia we’re up against, I think everybody’s kind of underestimated it. I would’ve thought Sgt. Pepper’s could’ve stopped the war just by putting too many good vibes in the air for anybody to have a war around.

When I wrote about this quote last year, I noted that a decisive percentage of voters who were old enough to buy Sgt. Pepper on its first release ended up voting for Donald Trump, just as some fans of the Whole Earth Catalog have built companies that have come to dominate our lives in unsettling ways. And I no longer think of this as an aberration, or even as a betrayal of the values expressed by the originals, but as an exposure of the flawed idea of freedom that they represented. (Even the metaphor of the catalog itself, which implies that we can pick and choose the knowledge that we need, seems troubling now.) Writing once of Fuller’s geodesic domes, which were a fixture in the Catalog, Brand ruefully confessed that they were elegant in theory, but in practice, they “were a massive, total failure…Domes leaked, always.” Brand’s vision, which grew out of Fuller’s, remains the most compelling way of life that I know. But it leaked, always.

Quote of the Day

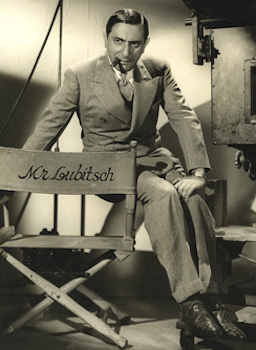

A tip from Lubitsch: Let the the audience add up two plus two. They’ll love you forever.

—Billy Wilder, to Cameron Crowe in Conversations with Wilder